From eucalyptus trees to lyocell fibers: promises and limits of sustainable fashion

Lyocell from eucalyptus recovers over 99% of solvents in closed-loop production, uses about 600–800 liters of water per kg versus ~2,700 for cotton, and is biodegradable when FSC-certified

Eucalyptus: a sustainable fabric for quality and ethical clothing

Working toward a more sustainable and ethical lifestyle has pushed human activity to explore alternative ways of producing goods. The clothing industry, however, has yet to reach the same level of environmental awareness achieved in sectors such as food or energy. Today, inexpensive polyester-derived materials still dominate the market, largely because developing alternative resources requires time, energy, and extensive research. Most fabrics currently available rely on chemically intensive production processes, and in the absence of reliable textile certifications that guarantee sustainable practices, many of these materials remain environmentally harmful.

This article explores how eucalyptus can be transformed into a sustainable fabric for quality and ethical clothing, while also addressing its limits and contradictions.

From eucalyptus tree to lyocell fiber: how a fast-growing plant became a textile resource

Eucalyptus is a woody flowering tree or shrub belonging to a botanical family that includes nearly 700 species. Native primarily to Australia and Southeast Asia, eucalyptus varieties now grow in Europe, the Americas, and Africa. Its rapid growth has long attracted interest, particularly for its essential oil, widely used for cleaning purposes and as a natural insecticide.

In the textile industry, eucalyptus is best known through lyocell, a semi-synthetic fiber derived from cellulose extracted from eucalyptus wood pulp. Until March 2018, the name Tencel was used exclusively as a synonym for lyocell. Today, however, the Tencel trademark applies to both lyocell and modal fibers, depending on the raw material and process used.

Tencel lyocell is produced exclusively from eucalyptus wood pulp sourced from forests certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and often also carrying the Pan-European Forest Certification (PEFC) seal. FSC certification ensures that the land used for cultivation is carefully selected, verifying that pre-existing flora has not been destroyed and that responsible reforestation and regeneration practices are applied. Only the strictly necessary amount of land is utilized, allowing eucalyptus trees to regenerate naturally.

The eucalyptus plantations used by Lenzing AG for lyocell production are located entirely in Europe, where the supply chain remains traceable, controlled, and comparatively transparent.

Lyocell manufacturing and closed-loop processing: reducing water, chemicals, and emissions

To date, no natural, artificial, or synthetic fiber can be considered genuinely ecological without verified textile certifications. The production of eucalyptus-based lyocell follows a process similar to other semi-synthetic fibers such as viscose bamboo, but with crucial technological differences that significantly reduce its environmental impact.

The eucalyptus wood is chipped and pulped, then dissolved into a cellulose solution using amine oxide. This solution is filtered, extruded through spinnerets, and spun into continuous fibers. Unlike traditional viscose, which relies on toxic chemicals such as carbon disulfide, the lyocell process avoids hazardous substances entirely.

What distinguishes Tencel lyocell from other regenerated fibers is its closed-loop manufacturing system. The solvent used during processing is recovered and reused at a rate of up to 99 percent, drastically reducing chemical waste. This loop also limits water consumption and energy demand when compared to both conventional viscose and cotton processing.

According to life-cycle assessments published by fiber manufacturers, lyocell production requires significantly less irrigation than cotton farming, as eucalyptus trees rely primarily on rainwater rather than artificial watering systems. Additionally, the smooth surface of lyocell fibers reduces friction during weaving and finishing, lowering mechanical stress and extending garment lifespan.

Air and water emissions generated during certified lyocell production are minimal and considered non-harmful, making it one of the lowest-impact textile fibers currently available when produced under strictly controlled conditions.

Blending lyocell and organic cotton: sustainability meets commercial reality

Tencel lyocell can be used on its own for ecological clothing, but it does not fall under the organic category unless it is blended with organic cotton. This distinction is particularly relevant from a regulatory and consumer-transparency perspective, as organic certification applies exclusively to agricultural practices, not to regenerated fibers.

Blending lyocell with organic cotton has become common within the fashion industry for both technical and economic reasons. Lyocell improves softness, breathability, and moisture management, while organic cotton contributes structural stability and familiarity for consumers. At the same time, blending helps brands offset the high production costs associated with lyocell, making the final garments more accessible without fully compromising sustainability goals.

From an end-of-life perspective, lyocell–organic cotton blends perform better than many conventional textiles. They are fully biodegradable and recyclable under industrial conditions. In controlled waste treatment facilities, the fibers can degrade completely in approximately eight days, returning to the biosphere without releasing microplastics.

Life-cycle analyses consistently show that the environmental footprint of lyocell blends is lower than that of both conventional and organic cotton alone. This advantage is largely due to the reduced land use required for eucalyptus cultivation, as well as lower pesticide input and water demand across the supply chain.

“One of the most important aspects of working with natural fibers is understanding the interconnectivity between Earth and human activity,” explains Asherah Kaliyana, founder of Nomadica Clothing. “These conversations around natural-derived fibers have opened up new perspectives on how to manufacture products while remaining as respectful of the environment as possible.”

Kaliyana acknowledges that producing textiles inevitably requires energy and water, but emphasizes that eucalyptus fiber allows for reduced consumption. “We choose not to dye the fabric after production, leaving the natural color created by the process. At the moment, we haven’t found completely natural dyes that are both environmentally compatible and sufficiently stable on this fiber. For this reason, we only dye garments made from organic cotton or silk.”

The cost and complexity of working with eucalyptus-based fibers

Working with eucalyptus fiber remains expensive and time-consuming. Transforming lyocell into yarn requires slower processes, including light-twist spinning that releases small amounts of fiber at a time. Techniques such as pleating are possible, but further extend production timelines.

“During the pandemic, we experienced a rise in sales,” Kaliyana continues. “We interpreted this as a growing interest in organic clothing. When human activity slowed down, people had the time to reflect on the consequences of our industry and became more willing to invest in ethically produced garments.”

Lampoon review: why sustainability means nothing without certifications

Despite its ecological advantages, lyocell cannot be considered a universal solution for sustainable fashion. In many regions of the world, organic and conventional cotton farming remain essential sources of income for millions of people. A rapid or uncontrolled shift from cotton to lyocell could disrupt local economies, undermine agricultural livelihoods, and create new forms of dependency within global supply chains.

Unlike cotton, eucalyptus is a woody material that requires substantial industrial processing to become wearable fiber. This transformation demands energy input at multiple stages, from pulping to spinning. As with other textile fibers, lyocell production also raises concerns related to labor conditions, particularly in eucalyptus plantations located in countries with limited regulatory oversight.

Without independent certification systems, there is no guarantee that eucalyptus plantations are managed responsibly or that surrounding ecosystems remain protected. Large-scale monoculture plantations can lead to soil depletion, biodiversity loss, and competition for water resources when not properly controlled.

The Tencel trademark addresses many of these risks by certifying that lyocell production meets strict environmental and social criteria. FSC-certified forests ensure that eucalyptus cultivation does not result in deforestation and that reforestation practices are enforced. Supply chains are monitored to guarantee compliance with labor standards and environmental safeguards.

However, increasing global demand for lyocell inevitably places pressure on land use. In countries such as India and Bangladesh—already facing severe deforestation and ecosystem degradation—the expansion of eucalyptus plantations has contributed to environmental stress when certification frameworks are absent or weak.

Tencel-certified lyocell avoids these issues by sourcing exclusively from European forests governed by FSC standards, demonstrating that regenerated fibers can be produced responsibly only when certification, transparency, and geographic accountability are firmly in place.

Nomadica: spirituality, responsibility, and certified eucalyptus textiles

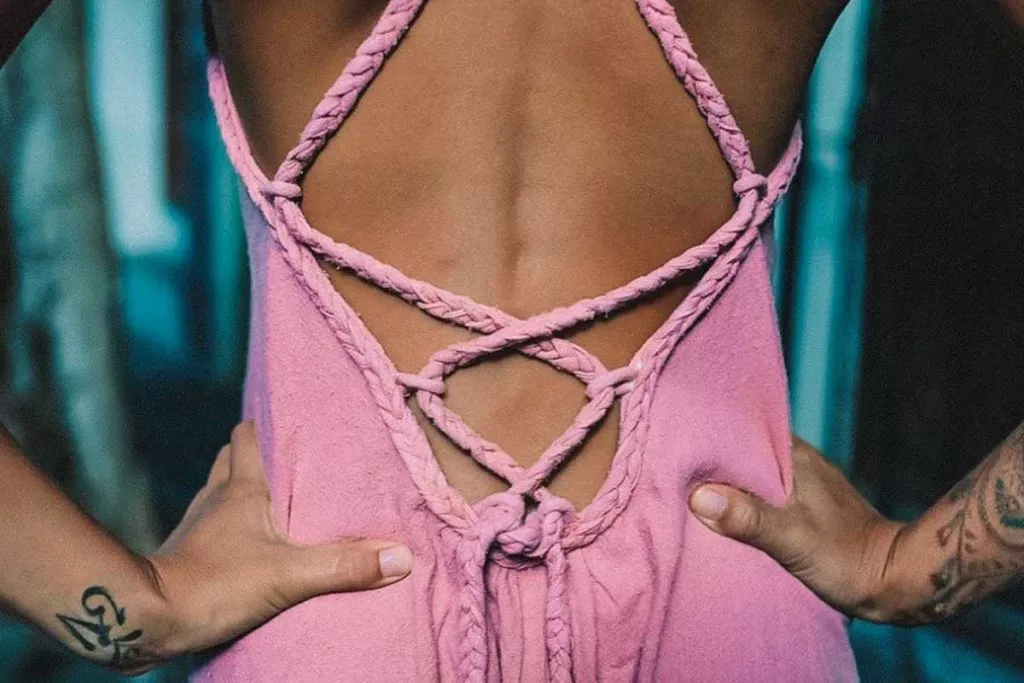

Nomadica is a fashion brand built around the relationship between spirituality and the human–Earth connection. The brand encourages consumers to approach clothing purchases with greater ecological awareness.

Its collections are developed using Tencel-certified eucalyptus fibers, ensuring that the yarns employed protect rainforests, ecosystems, and local economies. Through certified sourcing and responsible production, Nomadica positions eucalyptus-based textiles not as a trend, but as part of a broader reflection on how fashion can evolve toward ethical, transparent, and environmentally grounded practices.