Glyptic: an ancient craft saved from oblivion by one Maître d’Art, Philippe Nicolas

A jewel depends on the level of exhaustion of its creator. Métiers d’art: the art of carving stones and gems in high jewelry – calling it ‘glyptic’ may be reductive, notes Philippe Nicolas

Glyptic mastery at Cartier: Philippe Nicolas on carving hard stones and the future of a rare art

In any high jewelry atelier, pieces are brought to life by skilled experts, each with a specific responsibility. Without the support of high jewelry houses like Cartier, some of the métiers d’art—the traditional craft professions—might completely disappear. Glyptic, the rare art of carving stones and gems, is one of those endangered crafts that Cartier is actively working to preserve and promote.

This dedication is reflected in collections that often include a few pieces showcasing a carved or sculpted stone. How difficult is it to carve a stone? Are all stones alike in terms of carving? And what exactly is glyptic? Many questions—and one man who can answer them all: Philippe Nicolas, the head of Cartier’s in-house glyptic atelier. In this in-depth conversation, Nicolas sheds light on the nuances of his craft and what it means to be a contemporary stone sculptor in the world of high jewelry.

From student to Cartier’s glyptic master: a personal journey into carving hard and fine stones

In 2010, Cartier entrusted Philippe Nicolas with the mission of opening a workshop dedicated to training a new generation of experts in glyptic. The goal: to ensure the continuation of this delicate and complex craft. Now in his sixties, Nicolas defines himself as an engraver, carver, and sculptor of both hard and fine stones. His path began at the age of sixteen, when he found himself torn between a profession in the natural sciences or one in the applied arts.

“In the end, I enrolled at the École Boulle, followed by the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts of Paris,” he recalls. “While at the École Boulle, I studied in the carving atelier. For four years, several hours per week, I learned how to engrave glass. This was followed by a stint at the Paris Beaux-Arts School.”

“There, in the workshop dedicated to carving hard and fine stones, I learned that the techniques for glass and stone were identical.” However, he soon realized that making a living by sculpting glass would not be sustainable. “The development of industrial processes—engraving with acid or screen printing—made the option to work as an artisan unviable.”

Transitioning from glass to stone carving in high jewelry ateliers

Sculpting stones therefore appeared as the most viable choice. After leaving the Beaux-Arts, Nicolas applied to high jewelry houses while simultaneously teaching applied art and drawing. “I understood that the only way I could pursue my art was to work for high jewelers,” he explains. His ambition had never been to become a designer, but rather an artist and sculptor.

In 1981, Nicolas began making pieces with hard stones for the prestigious Place Vendôme houses. “It was not easy, to say the least. I had to quickly learn the ropes—especially abiding by the exacting rules of high jewelry. As a self-taught sculptor of hard stones, this was quite daunting.”

From 1985 to 2005, he worked exclusively for a single high jewelry house. He credits those twenty years with enriching him on both personal and artistic levels. “There I learned precision whilst perfecting my technique.”

A personal mission to pass on the dying art of glyptic to future generations

Throughout his career, Nicolas has always prioritized the importance of passing on his craft. Yet he observed that most high jewelry houses, and even his contemporaries, did not necessarily value preservation. “Glyptic masters at the time would not readily share their expertise,” he remembers.

In 2005, Nicolas opened his own workshop near Place Vendôme. Working on-site and in close collaboration with jewelers meant that his studio “quickly drew most of the high jewelers who wanted me to work for them.” This reputation led to his appointment as Maître d’art (Master Craftsman) in 2008, a title awarded to artisans who excel in their art and are committed to transmitting it to the next generation.

However, following the 2007–2008 financial crisis, the momentum came to a sudden halt. “One afternoon in 2009, I started to receive calls from all the high jewelers, one after the other, canceling their orders.”

A new chapter with Cartier: the first and only in-house glyptic atelier in high jewelry

In 2010, Cartier CEO Bernard Fornas offered Nicolas the opportunity to open an in-house glyptic atelier. The aim was to ensure the survival of glyptic through dedicated institutional support. In 2015, Philippe Nicolas was named Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres—a recognition made possible thanks to Cartier and the Comité Colbert.

Cartier’s in-house atelier now includes four people, including Nicolas, and notably three women. One is a Sicilian craftswoman trained in Rome in the art of medal and coin making.

“I cannot explain why, but this is a line of work that has become feminized,” he says. “It is quite difficult to find young people who, beyond their interest for the technique, are willing to become glypticiens. It is hard work and requires self-sacrifice. They all come from art schools. Some have mapped out a business plan for their careers, which explains the slight turnover in our team for the past three or four years.”

Creativity, according to Nicolas, is the most important quality: “It is a quality that cannot be developed, but is inherent.”

“It would be wrong to rely solely on the fact that we are part of a prestigious house. This fact alone is not a guarantee that the work will attract applicants. It means that the continuity of our team is fragile.” One of his greatest satisfactions is having a former student work with him continuously since 2008. “She was my student when I was appointed Maître d’art.”

Understanding glyptic: the complexities behind carving hard stones

When asked how many people currently practice glyptic, Nicolas admits: “I actually have no idea how many carvers or sculptors there are. Making a living from glyptic is quite challenging, so you get many manifestations of the profession: ones that work on commissions, lapidaries, or proper sculptors. That said, in the high jewelry world, there is no similar atelier to mine.”

He cites the region of Idar-Oberstein in Germany as having a rich history in stone cutting and carving. However, “the difference resides in the location of the workshops. In France, it is in Paris, close to the high jewelry houses and the French kings who developed an interest in this craft. This means that French glyptic may be more creative, whereas in Germany, it is more ‘artisanal’.”

Glyptic is defined as the direct engraving of fine and hard stones. Historically, it differentiated carving from sculpting, but the term is relatively new. “The name is a sort of neologism that came about in the eighties. There was a push to index each technique within the realm of the art. Personally, I don’t really like this clinical separation. It reduces the craft to a technique.”

A tradition of patience, self-sacrifice and invisible artistry

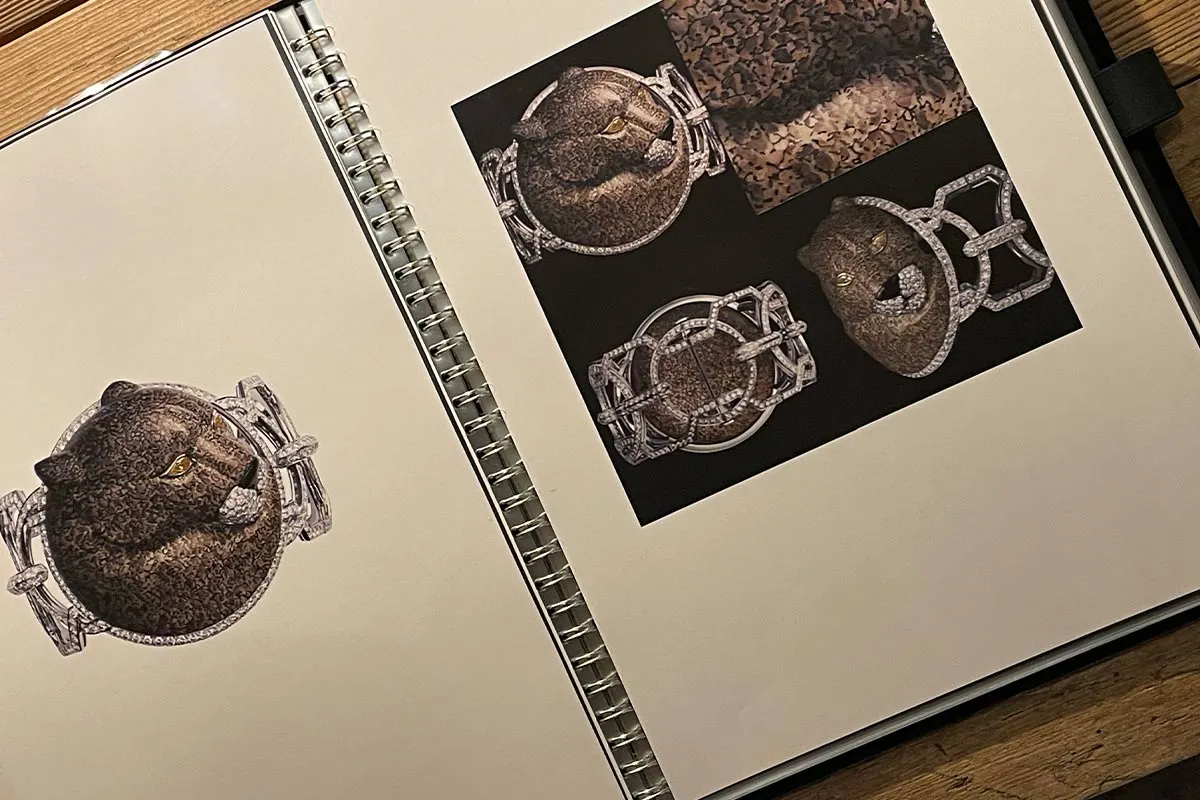

UNESCO has classified carving as part of humanity’s Intangible Cultural Heritage. As far back as history allows, humans have carved stone. In France, it was especially prominent in the 18th century and has always been a part of high jewelry collections, particularly at Cartier.

Glyptic is a demanding art form. “The culture of stones is not taught at school, not even in gemology courses. It is learned by experience alone.” A historian of glyptic, Ernest Babelon, once called antique cameos “monumental works of art.”

“Nadel, an 18th-century expert, said that ‘the level of success of a piece is dependent on the level of exhaustion of its creator.’” Nicolas adds: “The technique is at its greatest when it is least apparent in the work. L’art c’est de cacher l’art.”

The relationship between artist and stone: humility, instinct, and transformation

Nicolas and his team approach each stone with reverence. “After many years of practice and personal development, one approaches each stone with great humility. There are things we are able to achieve, others we are not and never will be.”

He adds: “Although I choose each stone, each stone also chooses me.” Black jasper, in particular, holds a special resonance for him. The connection, he says, is instinctive—and something he tries to pass on to his students.

Working with stones that are harder than metal requires specialized tools. “The idea is to remove matter by erosion. It is all about subtracting—or, as I often call it: learning how to renounce.”

He uses a fixed wheel equipped with rotating tools—steel, copper, brass, or wood—customized with abrasive materials. The tools vary in size according to the scale of the work. “For a work using intaglio carving, we use binocular loupes since the tool is no bigger than a pinhead.”

The greatest innovations in fifty years, according to Nicolas, are diamond-coated tools and the handheld micro motor. With a fixed wheel, one brings the stone to the tool via the micro motor, which is handheld. There are no set rules: each carver is looking for the best solution according to the outcome they want to achieve. «It takes great expertise to be able to enhance a stone, while overcoming the difficulties faced along the way, and still preserve spontaneity. I must say that I only remember the successes, and my most difficult piece is probably one that I have not yet started».

Creative autonomy and full control over stone sourcing at Cartier’s glyptic workshop

A distinctive feature of Philippe Nicolas’ atelier is its creative independence within Cartier. “When opening the workshop, I made it clear that I wanted to control the creative process as well. In many ways, our atelier is independent from Cartier’s creative studio. It is a highly unusual arrangement in the industry.” That said, the atelier naturally takes on projects brought in by the studio.

The stones come in all shapes, compositions, and levels of hardness. Some are gemstones; others consist of several minerals with varied inclusions. “Our job is to make the most of them despite these variations. What is essential is to overcome these hurdles whilst making them invisible.”

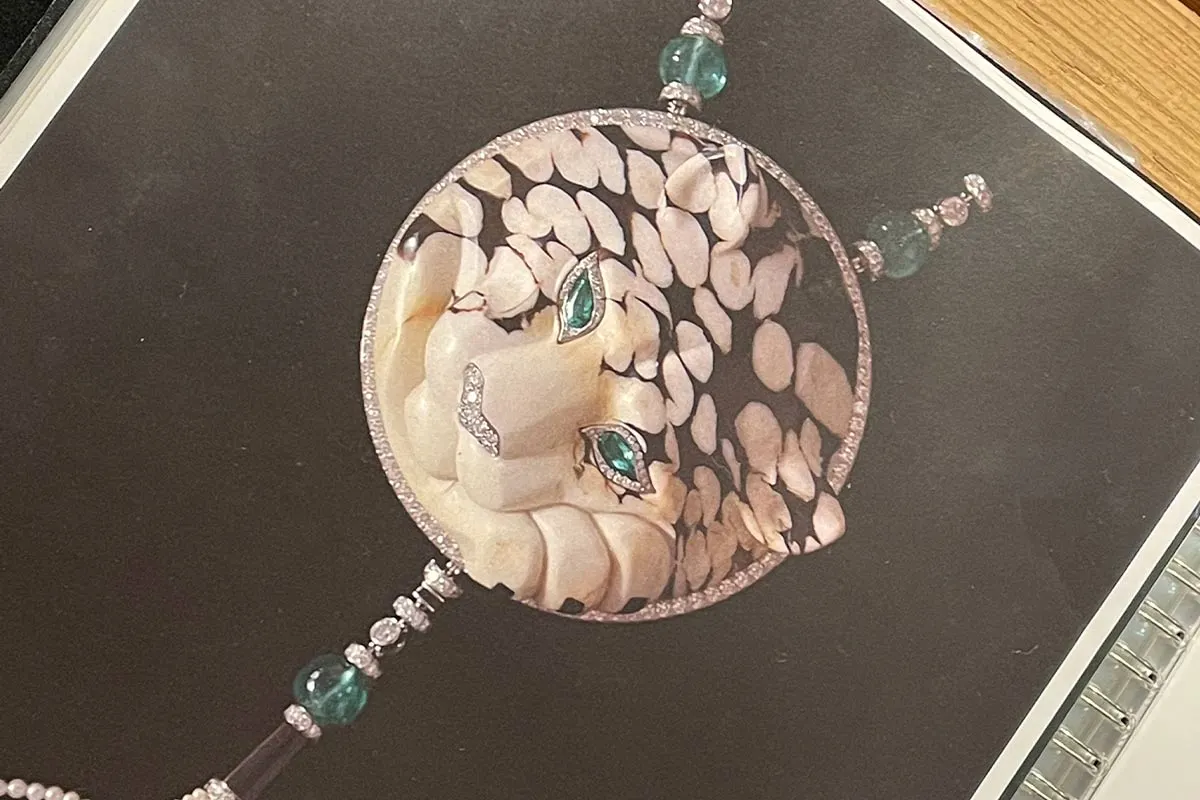

Occasionally, the team works with materials like petrified wood. “Petrified materials have become one of my trademarks since I was the first to introduce them in high jewelry. We are not necessarily into precious stones; rarity is more appealing.”

He points to chalcedony with an unconventional blue hue as an example. “The difference between a hard stone and a precious gem is simply the price. Between an emerald valued at €350,000 and a stone priced at 25 euros per kilo, the stake varies. But this initial difference is transformed thanks to our expertise and the resulting carving.”

Inside the creative process of carving a stone: assessment, trials, and execution

Every carving begins with an in-depth study of the raw stone. “Are there cracks? The more micro-cracks in a stone, the more complex the carving. Is the stone transparent? Is the color following a direction? How can one neutralize the inclusions through carving or sculpting?”

The interaction with light also plays a crucial role. “It is key to assess how the light affects the material in terms of how it will be worn or how the eye will catch it. It is all about evaluating how much volume one can extract, and it takes trials to check how the material reacts.”

Only once these elements are understood can the creative process begin. “Once this is all under control, and only then, can one forget about all the above and start free flowing, as though drawing on a blank canvas.”

Diamond, the hardest material with a Mohs grade of 10, remains among the most difficult to sculpt.

Mistakes and unpredictability: carving stones means embracing the unexpected

Is it possible to retouch a stone mid-process? “The margin of error depends on your assessment of the stone since at any moment there can be a surprise. When it comes to direct carving, it is always possible to modify or rectify a piece, and of course, this could change the final outcome.”

And what happens once a piece leaves the atelier? “As soon as it is produced, it takes on a life of its own—as a fantastic gemstone for its new owners or in the emotion it triggers. Observers have a role to play in the sense that they are the ones who extend the creation’s initial role. I am delighted and proud whenever a work exists in its own right.”

Portraits, commissions, and the emotional bond between client and artisan

Every piece Philippe Nicolas has worked on carries a memory. One of the most touching stories involved a Middle Eastern collector who requested a portrait of her father carved on a garnet.

“We never met her, yet working on her ring created a dialogue, an intimate connection with that client. Carving a portrait is a difficult task. Her husband liked the outcome so much that he then ordered stone carving portraits of each of their children.”

Another project close to Nicolas’ heart is a bracelet made of petrified wood. “I bought a piece of wood in America. It was dated as old as 20 million years. I designed a pattern of oak tree leaves so as to, in a sense, resuscitate the material to its old life. This bracelet will survive us all.”

From still life to inner life: capturing human emotion in carved expressions

According to Nicolas, facial expression in a sculpture—even of an animal—can reflect something deeply human. “The facial expression in an animal sculpture could be the expression of our own humanity. It makes it distinct from a still life.”

Nature is a constant source of inspiration: “Nature inspires us, and it is our task to translate the inspiration whilst avoiding caricature or trivialization. As long as my figurative creations are honest and sincere, I enjoy creating them.”

Maturity and experience help an artist know when a piece is complete. “There is always a risk of doing too much. That said, one learns how to identify when a creation is complete.”

The future of glyptic: teaching, adapting, and defending uniqueness in a digital world

As tastes evolve and digital tools become more prevalent, the future of glyptic is uncertain. But for Nicolas, its survival depends on one essential factor: transmission.

“In order to guarantee the future of glyptic, we have to start by passing it on in order to make it evolve. There is a risk that we could lose the art due to the increase in reproduction by machinery and modern technologies.” While he acknowledges that some technologies are helpful, he remains firm in his belief that:

“We have to keep hand-making unique pieces with unique stones—the only ones that are truly sought-after and desirable.”

By opening an in-house atelier led by a Maître d’art with full creative autonomy, Cartier has shown a rare and exceptional commitment to preserving this ancient craft. As of today, it remains the only high jewelry house to have done so.

Olivier Dupon