Sir Ridley Scott: The Strengths and Flaws of a Tireless Filmmaker

English director Ridley Scott celebrates his 87th birthday this November with the release of Gladiator II, a clear testament to his prolific and enduring spirit. But has everything he created truly been golden?

Ridley Scott: a late but iconic debut with The Duellists

In 1977, The Duellists, the first feature film directed by Ridley Scott, was nominated for the Palme d’Or and won the award for Best First Film. Scott was forty—a somewhat unusual age for a “debut.” But until then, one of today’s most acclaimed filmmakers was “just” a commercial director.

The idea of making a film of his own, instead of 30-second ads, first occurred to him ten years earlier, when he was still in his thirties. However, the prospect of risking a precarious career in a field that was generally less lucrative than advertising made him hesitate. He openly admitted in interviews that between the ‘60s and the following decade, Ridley Scott Associates—a production company founded with his younger brother Tony—was a cash machine bringing in hundreds of thousands of pounds, which today would equate to millions.

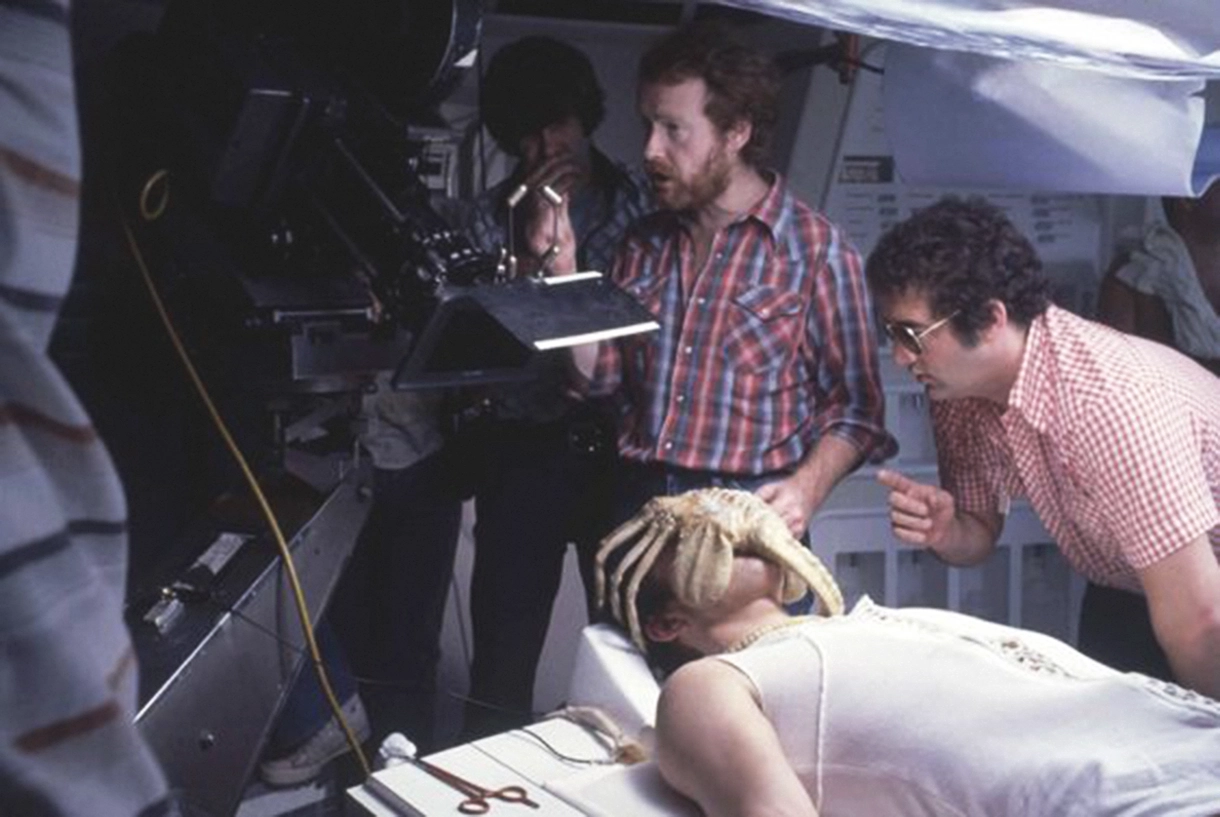

Scott, together with his brother and a select few other visionaries like Alan Parker and Adrian Lyne, formed an elite of directors that first dominated British television well into the ‘70s. Then, thanks to Alien (1979), which served as an icebreaker, they moved into the Hollywood blockbuster arena in the following decade.

From success in advertising to Hollywood conquest

This British clique that took control of American cinema also divided genres evenly among themselves. Tony Scott took on adrenaline-fueled action films like Top Gun and Beverly Hills Cop II. Ridley Scott (at least in the ‘80s) gravitated toward science fiction with Alien and Blade Runner. Meanwhile, Parker tackled cult films like Fame, and Lyne added a pinch of eroticism with Nine ½ Weeks (and, of course, Flashdance).

The “dynamic” vision of Ridley Scott: the cornerstone of his directing style

In Scott’s interviews, a word that frequently recurs is “dynamic.” Anything lacking it risks boring the audience. For someone who built the first half of his life and career on keeping people engaged—even if only for a one-minute ad—this idea means everything. Ridley Scott was ahead of his time, especially when it comes to the attention span we’re used to now in the age of reels and TikToks. This may be why many of his early films, now considered cinematic milestones, were box-office disappointments upon release. Only with time did they attain cult status.

Scott’s debut, The Duellists, the story of two Napoleonic officers who find themselves dueling for the rest of their lives over a trivial matter, was a critical success but not a popular one. The same is true of Blade Runner, which, surprisingly, grossed only $41 million against a $30 million production budget—a near-disaster for an ‘80s sci-fi epic.

Evidently, Scott’s “dynamic” approach didn’t immediately resonate with a society still somewhat unaccustomed to digital distraction, a collective mindset that could still appreciate the legendary slowness of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. No problem, though: among this list of strengths and weaknesses, Scott’s willingness to experiment without much fuss has been key to his success and, perhaps, his artistic (and possibly even biological) longevity.

Ridley Scott as the businessman with an artist’s soul

Ridley Scott is a businessman with an artist’s soul in a world where the opposite is more common. He has never hidden his entrepreneurial side, which we should at least appreciate. In his “gospel,” making money requires art, and making art requires money. Add to that a clear, sharp vision of each project, and you have the blueprint of the ideal 21st-century director.

Alien and Blade Runner: Ridley Scott’s sci-fi contributions

After his debut triumph at Cannes, Scott was inexplicably approached in 1978 to direct a sci-fi horror, which we now know as Alien. Why him, a director whose first film was a Napoleonic story? As he confided to The Hollywood Reporter, despite the lack of depth in the plot, “I thought the script had an incredibly good mechanism. It was like, ‘And then, and then, and then.’ I got to a page that said, ‘And then this thing comes out of the guy’s chest,’ and I thought, ‘This is why four directors passed on it—I was fifth on the list.’”

Between successes and flops: Ridley Scott’s entrepreneurial side

Scott’s combination of determination and lack of snobbishness—traits that paved his path to success—also led him to produce some real missteps, resulting in films that were ugly then and have aged terribly. Some of these aren’t even redeemable in terms of set design or costume design (be it period-accurate fashion in Napoleon or a connection to haute couture in House of Gucci), two elements Scott has always paid close attention to.

Take the example of Legend (1985), an embarrassing fantasy story filmed with a South American soap opera filter that feels like a parody of the fantasy genre. It’s filled with white horses with horns taped to their heads, wandering around artificial forests, while a young, painfully awkward Tom Cruise tries to save his love and the entire fairyland from evil goblins. For a fan of fantasy, Legend is a literal punch below the belt.

The lowest point, however, is arguably Black Rain (1989). Here, beyond the macho tone of a cop film centered on the Yakuza and set between New York and Tokyo, the insurmountable problem is that the protagonist, detective Michael Douglas, calls every Asian person he addresses “Charlie”—a slur from the Vietnam War era used by Americans to refer to the Viet Cong. After hearing it a couple of times, you’re ready to close the tab and look for something else to watch.

Ridley Scott today: from the Alien saga to Gladiator II

In August, Alien: Romulus, a new chapter in the series, was released, not directed by Scott but still produced by him. Then, in November, when Scott turns 87, Gladiator II will hit theaters. This relentless spirit of a director with the candor and drive of England’s postwar working class seems far from considering retirement.When you’re as hyper-productive as Ridley Scott, the famous “law of large numbers” often applies: quality sometimes takes a backseat to quantity. But Blade Runner compensates for three or four Black Rains. Besides Ennio Morricone, it’s hard to think of another equally prolific and long-lasting figure in cinema. As The Guardian pointed out, Martin Scorsese is five years younger than Scott. Yet, while Scorsese often reflects on mortality in recent interviews, Scott fills his press talks with jabs at the French and wild tales of baboons. “Well, since [Scorsese] started Killers of the Flower Moon, I’ve made four movies.” Slightly competitive, wouldn’t you say?