India’s colonial legacy: a journey through Udaipur, Jaipur and the echoes of the British Raj

India confronts its colonial past in the contradictions of everyday life, where economic gaps and uneven infrastructures echo policies of extraction that continue to influence development across cities and regions

India and the unresolved legacy of colonialism: why the past never fades in the subcontinent

In much of the world — from neighboring Southeast Asia to poorer regions of Africa — the blame placed on the West for colonialism has gradually thinned, overtaken by present-day concerns. In India, however, every daily contradiction acts as a reminder, exposing Europe to the shame of its own history. Even the simple choreography of traffic, which openly violates road regulations, seems to echo centuries of imbalance and intrusion.

Udaipur’s lakes and the memory of empire: alliances, second sons, and the business of colonial dreams

Walking along the lake that stretches from the palace toward the jungle, one begins to understand the height of the dam and the vast forest lying below. In Rajasthan, European troops once forged alliances with local maharajas who traded privilege for profit, exchanging sovereignty for wealth extracted from their lands.

During an early stroll, Lucio Bonaccorsi recalls how one ended up in the colonies: fugitives escaping justice or the younger sons of aristocratic families, dispatched abroad so that inheritance could remain intact for the firstborn. Many became the first true self-made men of export-based commerce. Bonaccorsi — himself the second-born prince of a Sicilian family — remembers reading about Belgian colonialism, notoriously brutal in its exploitation of people and resources. Italians in Ethiopia and Eritrea, by contrast, approached colonialism with less nationalism and more investment in infrastructure — optimistic ventures whose promised returns never materialized.

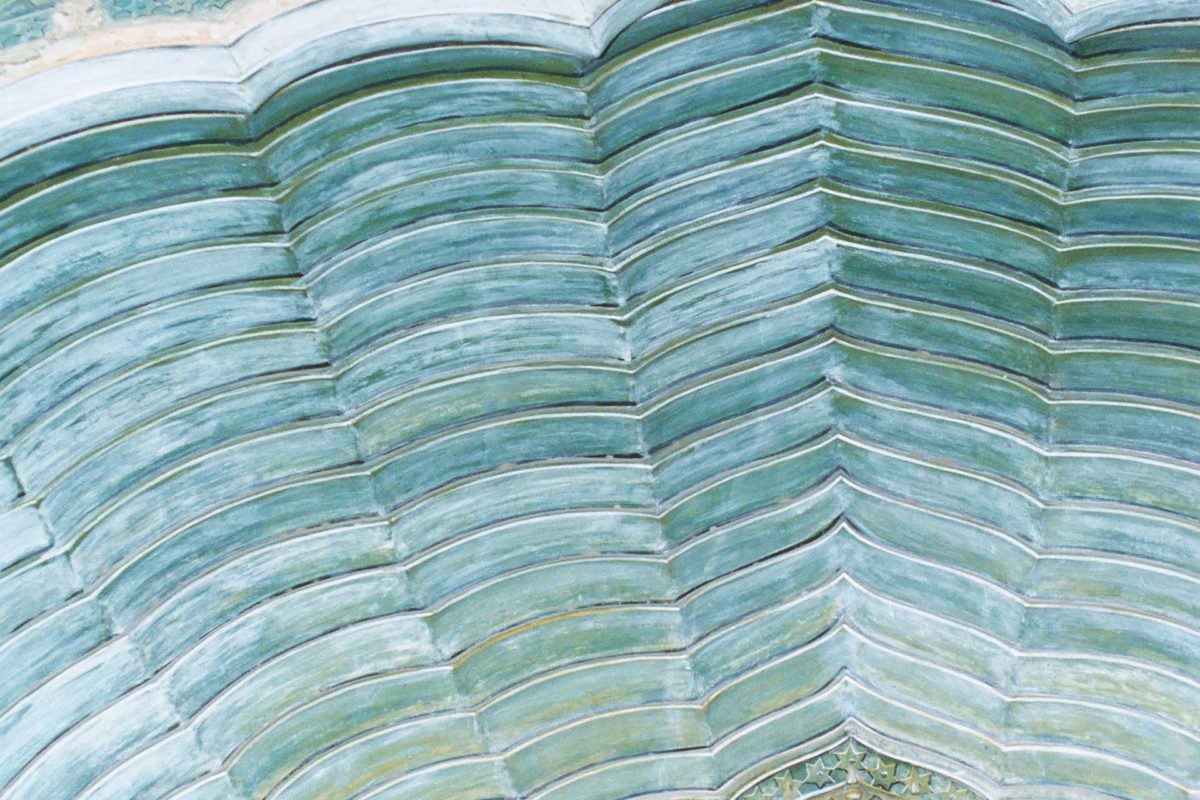

Udaipur’s lakes are a miniature Istanbul: artificial waters dating back to 1362, built to collect monsoon rain and groundwater. Their interconnected basins, joined by narrow bridges, now provide work for sixty percent of the city’s population.

Gandhi’s Salt March: how a handful of salt shattered the British Raj

On February 27, 1930, Gandhi published When I Am Arrested in Young India, denouncing the injustice of the British salt laws. Indian salt production had been banned in favor of English imports, sold at a staggering 2,400 percent markup — an impossible price for ordinary families.

Gandhi announced a march to the coastal village of Dandi to defy the law openly, knowing that peaceful civil disobedience could mobilize the masses and attract the global press. In a letter to Lord Irwin dated March 2, he wrote: “You are getting 11,200 annas per day against India’s average income of nearly two annas per day… a system that provides such an arrangement deserves to be summarily scrapped.” Ignored by Irwin, Gandhi replied, “On bended knees I asked for bread and I received stone instead.”

That morning, Ba Gandhi placed vermilion paste on the foreheads of her husband and the marchers. Gandhi warned: “You must be prepared to die. The British may use guns, but you must not fight back.”

They walked 240 miles in 24 days. Crowds joined. Flowers rained from windows. By the time they reached Dandi, international journalists were watching. Gandhi waded into the sea, gathered a handful of salt, and broke the law with a single symbolic gesture.

The next march toward the Dharasana depots met violence. British soldiers struck unarmed civilians with rifle butts, breaking bones and skulls. Webb Miller of United Press reported: “In eighteen years of reporting in twenty-two countries, I have never witnessed such harrowing scenes.”

Images spread worldwide. The end of the British Raj began there, in waves against a salt-stained shore.

The palace gardens of Udaipur: mirrored inlays, summer courts, and the quiet geometry of royal pleasure

Udaipur’s limestone inlays shimmer like distorted prisms. Craftsmen place fragments of curved glass onto a sketched pattern, pour liquid lime over them, then reveal the design once the slab is flipped: a glimmering stencil that alters reality through its convex reflections. The oldest pieces show denser lime and deeper-set glass — motifs of the tree of life, flowered vases, cascading leaves.

The Lake Palace courtyard still displays these works. Its fountain brims each morning with fresh petals, while a guard swings a white flag, snapping it like a soft cannon to scatter pigeons. The royal women’s garden remains a cultivated jungle of shade and scent, once an orchard meant to soothe princesses.

The Maharani Suite remains dim, filtered through tiny stained-glass windows. To visit Udaipur without staying overnight is to miss its soul.

City Palace and the romance of Rajput grandeur: islands, monsoons, and marble histories

City Palace rises like a Eastern echo of Monte Carlo, softened by Indian ease. From Lake Pichola, one sees how the structure merges with the hillside’s ancient trees, a nineteenth-century romantic tableau.

Botanical gardens host Royal Palms whose trunks resemble concrete pillars. Pigeon coops are woven like pieces of modern design. Everything is carved from marble.

During Holi, fountains brim with petals in every shade—except lapis blue, a sacred color. Udaipur was once home to a celebrated painting school. Artists used squirrel-tail brushes to paint faces with photographic precision.

A single marble block carved into a two-meter pool was once filled with silver coins at a new maharaja’s coronation — the last time in 1930, when generosity became too expensive.

Belgian stained glass, ivory portals, camel-bone doors: a mosaic of global trade embedded in local royalty. In 2011, drought exposed the lakebed entirely, revealing palace foundations ten meters high, reachable on foot.

Jaipur’s restless roads: chaos, pride, and the impossible logic of Indian traffic

The road toward Jaipur grows smoother. Saplings are shielded from goats; drainage sinks below the asphalt. Advertisements replace road signs. Plastic waste demands new technologies for decomposition.

Population density raises questions that numbers alone cannot answer.

Paan stains — bright red—mark walls and sidewalks across South and Southeast Asia. Signs attempt regulation, seldom enforcement.

Drivers advance against traffic, loyal to informal agreements with restaurants and shops that provide commissions. Animals wander freely: cobras at night, dogs by day. Braking for livestock is forbidden to avoid chain collisions. Roads feel like a video game where reflexes matter more than rules.

Challenge an Indian’s pride by suggesting the quality of life is insufficient, and doors open: the hidden city, the places locals keep for themselves.

Amber Fort and the contradictions of intimacy, hierarchy, and desire

At Amber Fort, the young generation searches for physical contact — friends with arms draped over shoulders, couples hand in hand, gazes bold. Masculine affection is common, yet homophobia persists despite Hinduism’s own acceptance and the Kamasutra’s pages on same-sex love.

Rooms once reserved for women hide behind small Belgian-colored windows that allow them to see without being seen.

Tourists ascend on female Indian elephants — the calmer sex — allowed no more than four trips a day before resting on bananas and sugarcane. These elephants may be the most pampered in the world.

From atop the fortress, Saffron Garden stretches across the lake. Crocodiles once thrived there, now long gone.

The Crystal Gallery, built in 1623, blends Belgian glass with Afghan lapis lazuli. Only royal men, their wives, concubines, and eunuchs — no non-royal testosterone — could enter. One emperor, in the sixteenth century, demanded twelve wives: one for each zodiac sign.

Rajasthan’s mineral wealth shaped its jewelry heritage. Today Jaipur remains a global gem center, home of Samir Kasliwal of The Gem Palace, whose Italian upbringing and Indian roots created a cosmopolitan circle admired across continents.

Modern royalty and the making of a global Jaipur: polo, palaces, and a new aristocratic identity

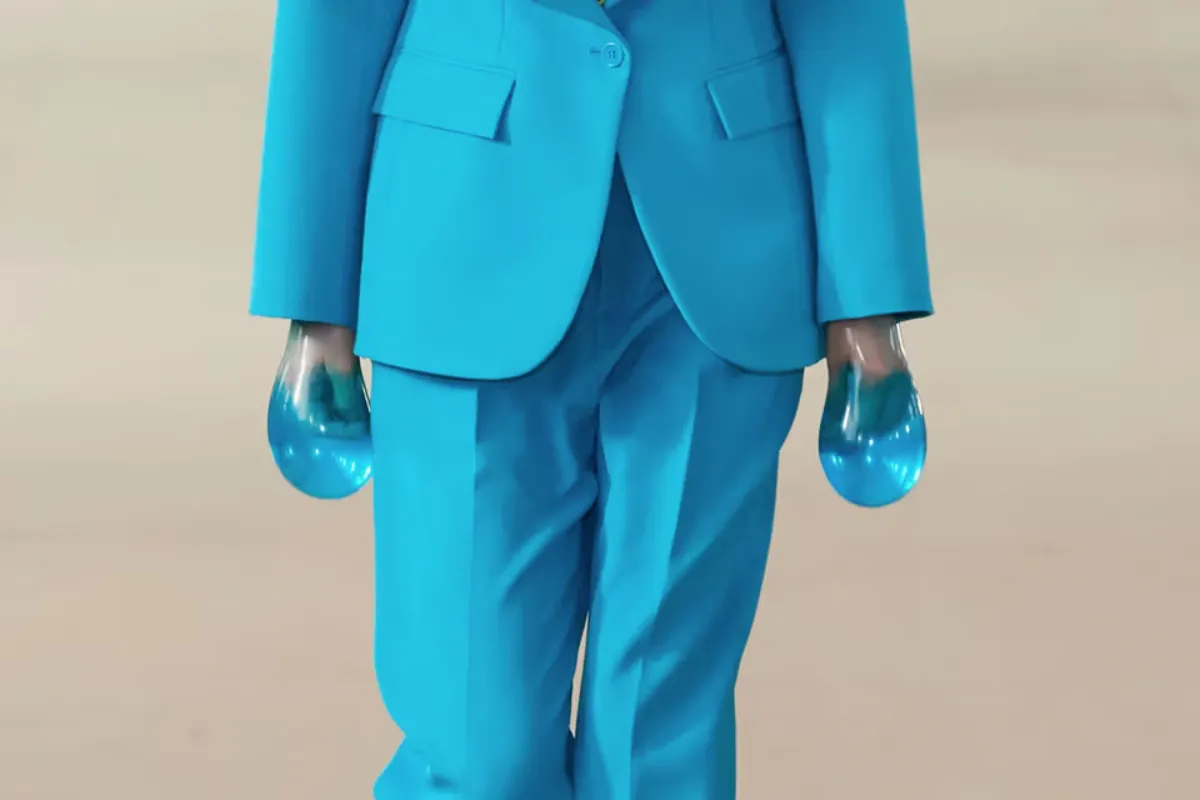

Padmanabh Singh, Jaipur’s 22-year-old maharaja — Pacho to Europeans — lives between India, Rome, and London. He hosts global aristocracy in palace gardens, turning Jaipur into a destination of social prestige. A national polo champion, he has walked Milan’s runways and attended Armani shows.

Rambagh Palace, owned by the royal family and leased to Taj Hotels, has hosted queens, actors, and celebrities. Peacocks roam the gardens; heritage rules forbid altering the historic indoor pool, which cannot be heated. French Empire gazebos shade the grounds, and morning croissants carry the scent of rose under the milky Indian sky.

From firangi to OCI: how the meaning of foreignness shifted with India’s colonial scars

OCI — Overseas Citizen of India — defines immigrants who have earned Indian citizenship. Once, foreigners who integrated were celebrated as firangi, a term now used pejoratively, stained by colonial memory. It once evoked European talent; today it carries resentment.

Vasco da Gama arrived in 1490, founding the Portuguese Estado da Índia, Europe’s first colonial outpost in India. In 1534, Garcia de Orta — a Jewish physician fleeing the Inquisition — reached Goa. His treatise on Indian botanical medicine helped shape tropical medicine. The Inquisition would later reach India in 1560, urged by missionary Francis Xavier.

Augustine Hiriart, a Basque fugitive accused of counterfeiting, arrived in the early seventeenth century. Emperor Jahangir named him Hunarmand — “skillful.” He designed thrones with lion-shaped legs and embedded rubies, carving forms reminiscent of Swiss guards at the Louvre. “If fantasy were a kingdom, this land will never be subdued to it.”

A last glimpse: a father, a book, and the quiet return from India

At the airport homeward, a father and his two teenage children sit with calm, deep-set eyes. The daughter, hair hastily gathered, helps her father solve an issue; the son quickly falls asleep after takeoff. Under the reading light, the father continues through a thick book. As he turns the page, the title becomes visible — one that anyone reading these lines could easily guess.

Carlo Mazzoni