The lotus plant: much is left to be discovered and not only about the fiber

If silk isn’t the first natural microfiber, then lotus certainly is. Acknowledging the ability to multitask within a community, Samatoa supplies women with work whilst keeping R&D in the fiber industry alive

Lotus fiber and textile innovation: scientific research, social impact, and circular production

In 2008, Cambodia experienced one of its recurrent droughts, severely affecting the production of mulberry leaves—the sole food source of silkworms. The resulting shortage of raw materials forced several producers to reconsider their dependence on silk.

Samatoa, a social business based in Siem Reap and founded in 2003 by Awen Deleval, was among those directly impacted. Unable to meet growing demand for silk, the company began exploring alternative fibers. While identifying fiber within plants or trees is relatively straightforward, the true challenge lies in extraction, transformation, and scalability.

“All plants contain fiber,” explains Deleval. “The challenge was finding a way to extract it, then spin it, weave it, and eventually dye it.” Among the many options tested, fiber extracted from the lotus stem quickly emerged as the most promising. According to Deleval, it “revealed a potential greater than any other fiber we explored.”

Lacking in-house textile scientists, Samatoa chose to collaborate with external research institutions, including laboratories in South Korea and the French Institute of Textile and Clothing. By submitting samples for independent testing, the company grounded its experimentation in scientific validation—an approach that lends credibility not only to the material itself but also to the business model supporting it.

“Our advantage comes from not knowing,” Deleval notes. “It forces us to research deeply. We don’t just study techniques—we learn from nature and try to understand processes that humans have never fully mastered.”

Lampoon reporting: why the lotus plant matters for the textile industry

The lotus is an aquatic perennial plant that thrives in shallow waters such as ponds, slow-moving lakes, and lagoons. Its leaves and flowers float on the surface, while long petioles—often reaching up to two meters—remain submerged. Native to southern and eastern Asia, the lotus holds strong symbolic value, traditionally associated with purity, enlightenment, regeneration, and rebirth.

In Cambodia, farmers harvest lotus flowers and seeds for food and local markets. Historically, the stems were left in the water as agricultural waste, regarded as having no economic value. Samatoa identified this overlooked byproduct as a viable textile resource.

By breaking open the stem and gently pulling it apart, thin strands of fiber emerge. In 2016, samples were sent to the French Institute of Textile and Clothing for analysis. The results identified lotus fiber as the first known natural microfiber in the world.

Microfibers are defined as fibers with a linear density below one dtex—less than one gram per ten thousand meters of yarn. Conventionally, microfibers are synthetic, typically made from polyester or polyamide. Lotus fiber, by contrast, is entirely natural.

Microscopic analysis revealed a complex internal architecture: the fiber surface is porous, resembling a sponge. This structure explains several of its key properties, including exceptional softness, lightness, and breathability. The porous surface enables rapid absorption and release of moisture, while the fiber’s elasticity allows it to return to its original shape, making the fabric naturally resistant to wrinkling.

Despite these findings, research remains ongoing. “We are still discovering its properties,” Deleval emphasizes.

From stem to textile: extracting and producing lotus fiber without chemicals

Samatoa’s production chain is intentionally minimal and excludes intermediaries. Farmers harvest lotus flowers using small, non-motorized wooden boats, as they have done for generations. Samatoa purchases the stems—previously discarded as waste—directly from them.

The process requires no chemical additives. “Unlike organic cotton, which demands large quantities of water, the lotus uses only the water already present in the lake,” explains Deleval.

Around 150 trained spinners, primarily women, are involved in fiber extraction. The work provides supplementary income and can be carried out from home, allowing workers to care for their children while remaining economically active.

Fiber extraction is a meticulous process. Each stem is snapped and gently pulled apart to release long filaments, which are rolled by hand to form thread. Fibers are tightly coiled within the stem, creating natural breakpoints every two to three centimeters. On average, a single stem contains approximately fifty microfibers and can be cut around twelve times.

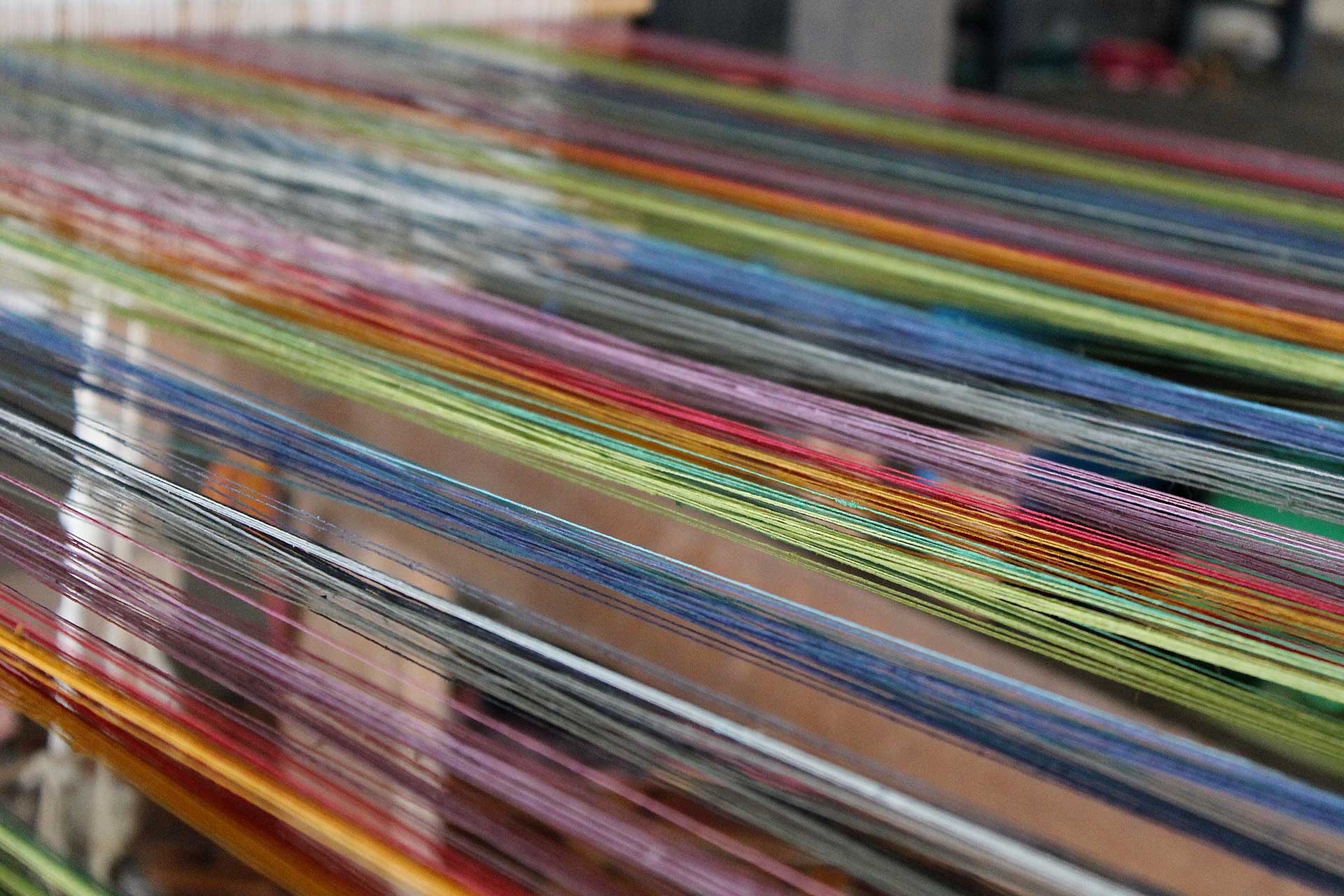

One yarn produced by a spinner contains at least six hundred microfibers. To produce one meter of lotus fabric, roughly forty thousand stems are required. Creating a small scarf takes about one month: around ten days for spinning and fiber preparation, followed by dyeing, softening, and weaving.

The dyeing phase represents the least sustainable aspect of the process. Threads are dyed before weaving using Oeko-Tex–certified dyes that exclude heavy metals. Natural dyes are not used due to limitations in color consistency, scalability, and storage—particularly for bespoke production.

Given the extreme delicacy of lotus fiber, traditional Cambodian handlooms have been adapted specifically for this material. These modified looms are located exclusively within Samatoa’s eco-textile mill and are used only for pure lotus fabric. Blended textiles can be woven in surrounding villages, where the fibers are less fragile.

“The lotus textile is timeless and non-mechanized,” Deleval explains. “It allows us to understand every step of what we are doing. If there is a quality issue, we see it immediately.”

Closing the loop: lotus fiber, agricultural waste, and circular economy experiments

Although stem harvesting prevents organic waste from decomposing in waterways, fiber extraction generates significant byproducts. For every 1,000 square meters of lotus textile produced, approximately 300 tonnes of residual stem waste remain.

Samatoa’s research and development efforts focus on reintegrating this waste into a circular system. One effective application has been mulching. In Cambodia, plastic sheets are commonly used to retain soil moisture, but they degrade into microplastics, depleting soil quality and shortening agricultural lifespans.

Lotus stem mulch performs the same moisture-retention function while enriching the soil with organic nutrients. By collaborating with local farmers, Samatoa closes the production loop—returning waste to the land from which it originated.

Another experimental avenue is lotus-based vegan leather. Deleval describes it as “a composite material made entirely from vegetable waste.” After testing competitor samples, Samatoa found that most alternatives contained plastic. “It reminded me of how bamboo fiber was once marketed as natural, despite relying heavily on chemical processing,” he notes.

Samatoa’s prototype lotus leather combines lotus fiber with a bioplastic base derived from glycerin, starch, and water. While the traditional fiber process relies on minimal machinery, scaling lotus leather production will require more advanced equipment.

Looking ahead, Deleval envisions a biogas system capable of converting production waste into renewable energy for communities surrounding the lake. “Using waste to generate electricity for free, permanently—that is our long-term vision,” he explains. While the infrastructure is not yet in place, the possibility remains central to Samatoa’s research philosophy.

Samatoa: social enterprise, textile research, and women’s economic empowerment

Samatoa is a social business based in Siem Reap, Cambodia. Founded in 2003 by Awen Deleval, the company initially focused on silk production before turning to lotus fiber research following the 2008 drought.

Today, Samatoa integrates scientific research, low-impact manufacturing, and socially responsible labor practices. By creating flexible, home-based employment opportunities, particularly for women, the company positions textile innovation as both an environmental and social project—one rooted in patience, experimentation, and long-term thinking rather than industrial speed.

India Gustin