Shall your fantasy be dismissed by some artificial intelligence?

The exhibition Cartier & Myths in Rome forces us back to the place where fantasy is born – the realm of myth – with a challenging question: will we remain stronger than an algorithm, or will it overpower us?

Louis Cartier and a journey through Italy: can imagination ever be defeated?

Traveling across the known world, Louis Cartier returned home with objects meant to spark new designs—wonders that could eventually become jewels. The culture of the Maharajas inspired what we now call the Tutti Frutti style: emeralds and rubies, interrupted by sapphires, carved with floral motifs to form flowing gardens of ivy, leaves, and petals. For Louis Cartier, reaching the edges of the world meant pushing himself to the edges of the unbelievable—a permanent, determined pursuit of amazement.

This was not nourishment for Cartier alone, but for the entire Maison as it rose within Europe’s entrepreneurial and financial landscape. The lesson remains valid today: imagination must be fed and trained. With what? With culture, yes—but not the culture of data and information, where an algorithm will always surpass us. What we need is a culture of connections, if culture today is to mean imagination, creativity and fantasy.

Cartier & Myths – a dialogue between ancient Rome and twentieth-century jewelry

Cartier & Myths is open at the Capitoline Museums until March 15, 2026. Why call attention to a jewelry exhibition staged among the statues of ancient Rome? To reinforce a simple truth: the manual skill of the human being is formed through a technical discipline that begins young and continues over a lifetime, and through a cultural education that allows us to process history and transform it into creative imagination.

Louis Cartier, a man of the early twentieth century, belonged to the most refined circles between Paris and London. Iron technology rose vertically with the Eiffel Tower; clouds of sky and steam shifted with the engines of yachts in the Mediterranean and locomotives running from Paris down into Italy, toward Rome. Rome still appeared as the imaginative center of the West, a fulcrum of historical, literary, and artistic balance. How could Louis Cartier’s imagination not explode the first time he arrived in the heart of Italy? Algorithms pale in comparison.

Louis Cartier and Classicism: the ages of Gold and Rose, with a reference to Roberto Calasso

Cartier read Latin, and Italy appeared to him as the core of classical culture—the measure born from the golden ratio. What we now call the Classical came to Italy from Periclean Greece. Classicism has long been associated with the “Golden Ages” in history—the Roman Empire, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment and its Neoclassical revival. Between these, eras of “Rose” unfold—a softness, a decadence—Mannerism, Romanticism—what estimated Italian writer and master Roberto Calasso placed under the tenue of Tiepolo’s pink.

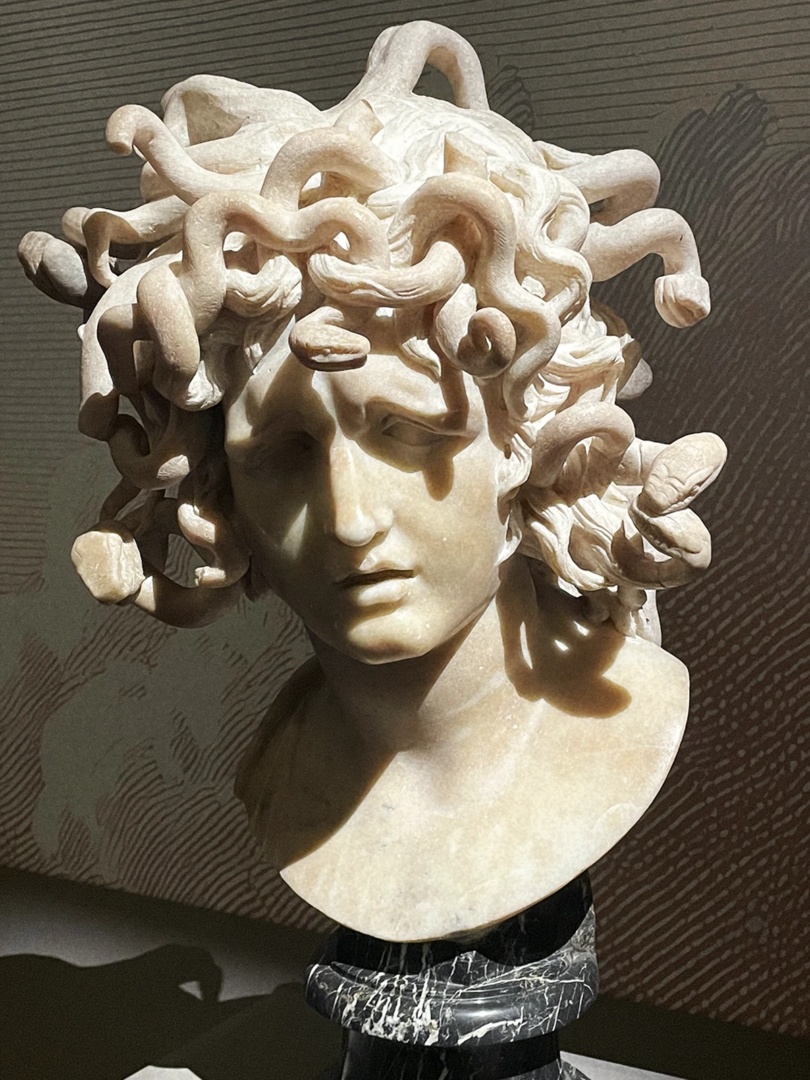

Cartier might have chosen another book by Roberto Calasso: The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, a banquet of mythological stories echoed throughout the exhibition. Tales where the divine enters the realm of the flesh, where the genesis of the world intertwines with desire, lightning pierces foam, and seduction becomes origin.

Let this text—these few minutes you’re giving it—serve as a small spark to reignite what you already know. Sparks found while walking through the halls of the Palazzo Nuovo on the Capitoline Hill, one of Rome’s seven hills; sparks capable of firing the synapses with which Atreyu rebuilds the Ivory Tower for the Childlike Empress.

The classical canon: Demeter, Venus – Cartier at the Capitoline Museums and the Castellani legacy

From the archival notes, we know that in 1923 Louis Cartier immersed himself in classical archetypes while studying the ancient remains of Pompeii and Herculaneum. The symmetry of a Venus replica, the harmony of nature, purity itself. Mythology served as metaphor—matrix of literature, religion, catalyst of the Western imagination. In classical myth, we find the plots of every love story and tragedy; in myth we find the foundations of psychoanalysis that led to the novels of the Last Century. Classical mythology still feeds our fantasy today—our creative expression, our provocations, our sensual and sexual license. The poetic art of turning desire into a song.

The wheat ear symbolizes Demeter, goddess of the earth’s fertility. It was placed on the heads of brides as a sign of welcome into the marital bed, of warmth and intimacy. The nudity of Venus is the Roman reproduction of the Praxiteles’ Aphrodite—her hand is modestly covering her intimacy, defining the very meaning of the word delicate. Every time we speak of delicacy, every time we offer a delicate touch, we are repeating a gesture learned from Venus.

In one of the most celebrated rooms of the Capitoline Museums—the one where the busts of Roman emperors are arranged chronologically—visitors stop before a Mariano Fortuny gown inspired by the bronze statue of Delphi, an emblem of the Severe Style developed around 460 BCE. From 1909 onward, the geometric language of Greek archaeological findings merged, through fashion magazines like this very Lampoon, with the vivid imagination of the Ballets Russes.

Beyond them, the display cases hold pieces from Cartier’s patrimony. Some highlight the connection between early twentieth-century craftsmanship and classical codes. Cartier’s intellectual references came from reproductions of archaeological artifacts circulating in Europe’s cultural journals, as well as from Roman jewelers who revived ancient Greek and Etruscan techniques. Among them, Fortunato Pio Castellani and his sons stand out. In addition to producing their own work, the Castellani restored the jewelry collection once owned by Marchese Campana, later purchased by Napoleon III for the Louvre in 1861. The collection’s journey from Rome to Paris stirred the imagination of designers across Europe, prompting a revival of classical motifs.

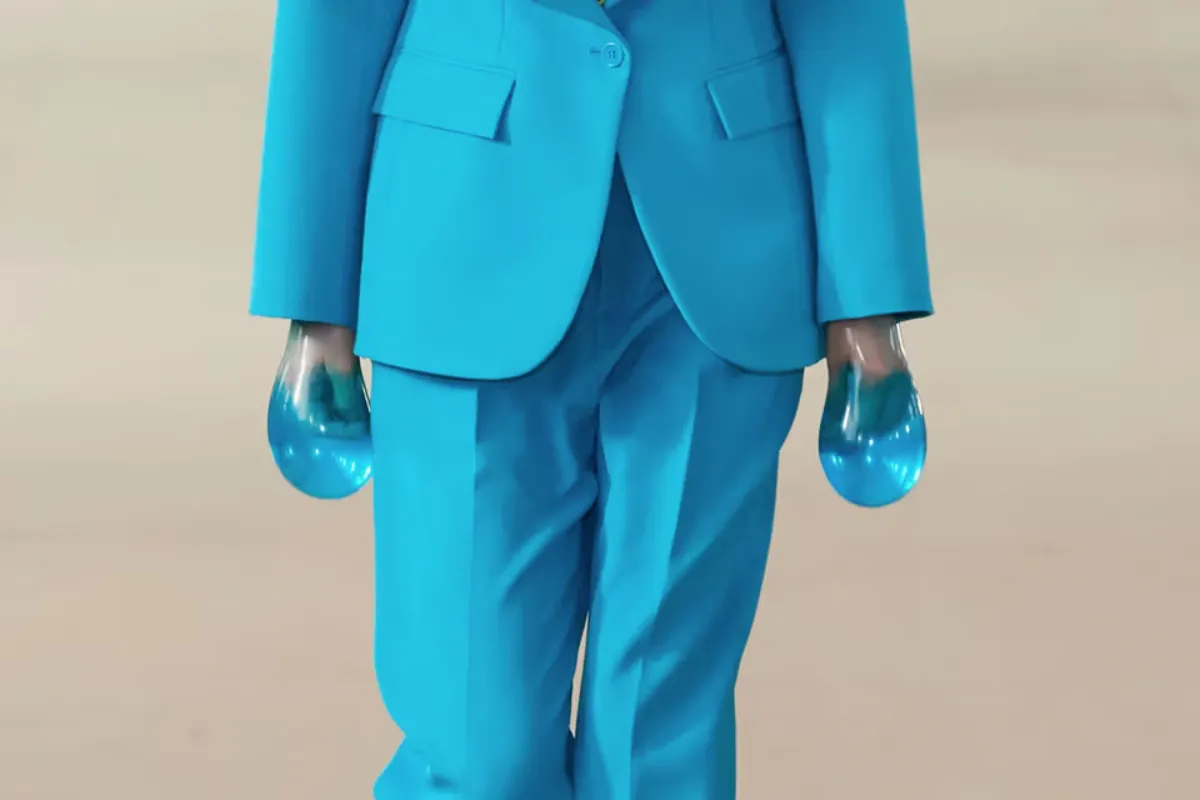

The same image will continue to move us: a man alone at his workbench, in a room full of noise, completely absorbed in what he is doing. Nothing else matters. His concentration is so deep that the noise first recedes, then disappears. Time flies—or stops altogether. His body strains: hands, back, breath. Yet none of it matters. He is moved solely by imagination, beating in rhythm with his heart.

Algorithms may eventually replace manual labor. Perhaps they will. They will never replicate the error that creates human wonder. Artificial intelligence cannot imitate the slight imperfection, the subtle misalignment, the soft line where a tool slid too gently—those tiny deviations that give life to beauty, to Venus herself.

Carlo Mazzoni