Sweat and rivalry: what happen when male bodies get too close

Locker rooms, showers and other discreet architectures have shaped male desire through rivalry, discipline and enforced proximity, from American art and cinema to photography and fashion

Male desire confined to locker rooms, showers and controlled spaces

Steam arrives before language. Tiles amplify sound. Water runs long enough to erase edges. Bodies move through the space following routines learned early and repeated without question. Towels drop. Skin stays warm. Nothing needs to be said. What remains visible is not action, but proximity.

Throughout the twentieth century and into the present, American visual culture has repeatedly returned to spaces that present themselves as practical and discreet: locker rooms, communal showers, public bathrooms. Environments designed for function, hygiene and discipline. Places where male bodies are allowed to be exposed, pressed together, touched – provided that desire remains unnamed.

These are not neutral settings. They are architectures that regulate masculinity. Heat, sweat and contact are tolerated only because they are justified by sport, work or cleanliness. Desire survives by adapting to function, embedding itself in routine.

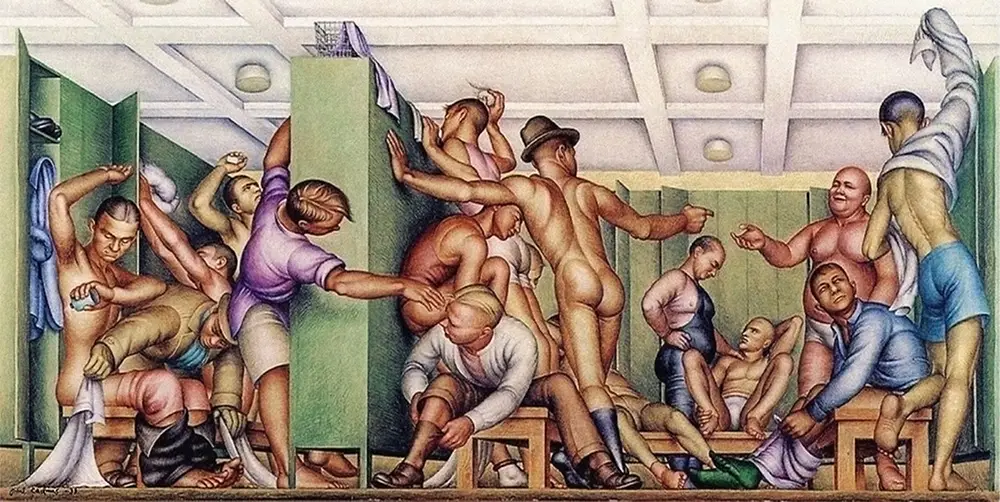

Paul Cadmus in the 1930s: repression as the engine of desire

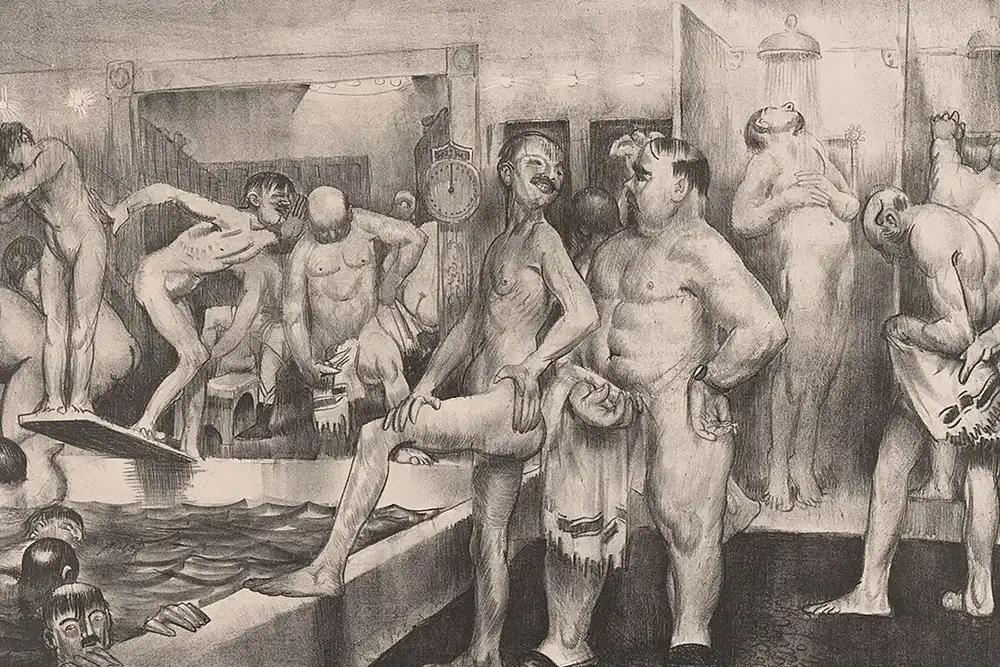

In the 1930s, Paul Cadmus gives form to this tension with unsettling clarity. Working within a puritan, moralistic and censorial America, Cadmus paints male bodies saturated with sexual charge and yet structurally prevented from release. His figures crowd one another, invade space, lean too close. Muscles swell, gestures linger, gazes hover without resolution.

The erotic tension in Cadmus’ work is explosive and costipated at once. Desire is not absent; it is compressed. Forced to drip through posture, friction and proximity. It operates like a chastity belt imposed by society, preferring voyeurism to liberation. Wanting circulates, sharpens, ferments.

Here repression is not the opposite of desire but its engine. Masculinity becomes a performance of restraint under which erotic tension accumulates until it destabilizes the image itself.

Bodies under discipline: George Bellows and the early twentieth century

A similar logic appears in George Bellows’ Shower Bath (1917). The scene is dense, aggressive in its physical compression. Bodies overlap, indistinct, pushed together by architecture rather than intention. Hygiene becomes a pretext. What remains is discipline.

The male body is collective, exposed, regulated. Desire is not staged but unavoidable. The shower suspends individuality, replacing it with friction. Nothing resolves. The space does not allow escape, only repetition.

Locker rooms in American cinema: rivalry after impact

Cinema inherits this structure rather than inventing it. Locker rooms appear not during action but after it. In Raging Bull(1980), violence withdraws into the changing room once the fight is over, when bodies are still charged and language fails. Any Given Sunday (1999) fills the space with noise, hierarchy and ritual. Foxcatcher (2014) drains it of warmth, turning it into a site of control and unease. Moonlight (2016) allows vulnerability to surface briefly before routine closes in again.

Sex is never shown. What matters is the interval. Bodies still warm. Breath not yet regulated. Skin marked. Rivalry authorizes proximity. Physical confrontation replaces intimacy. Touch is permitted as collision, correction, containment. Heated rivalry is not metaphorical. It is a system that keeps bodies close while refusing interpretation.

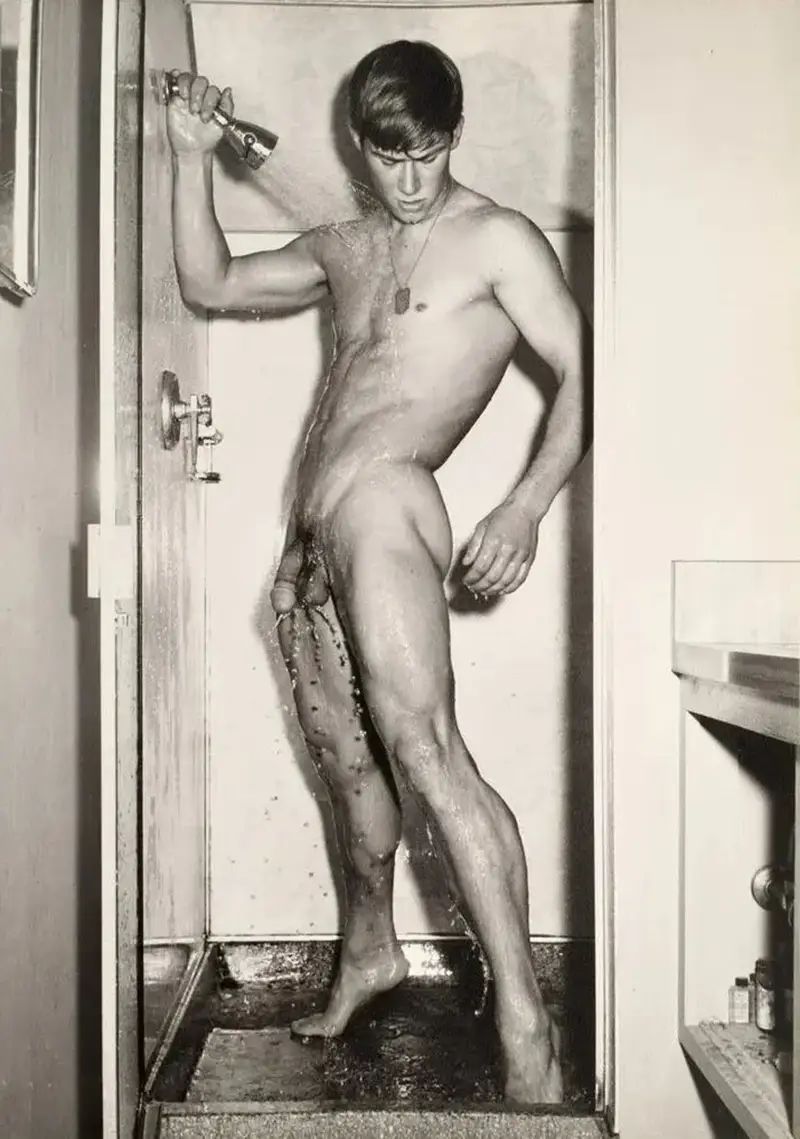

The shower as suspended ritual

The communal shower intensifies this logic. Mandatory nudity. No privacy. Steam dissolves outlines. Sound precedes sight. Time stretches without direction.

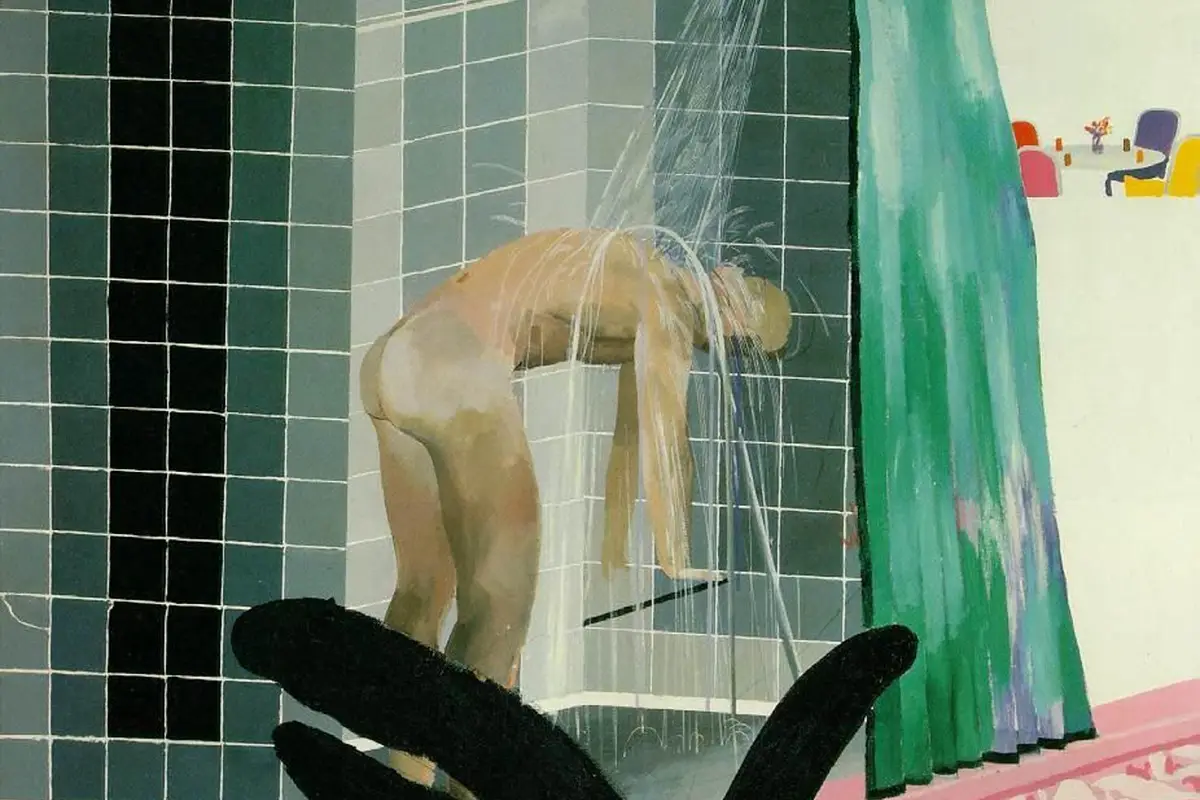

In Man in Shower in Beverly Hills (1967), David Hockney isolates the ritual, removing rivalry but not vulnerability. A single body framed by tiles, absorbed in repetition. Cleanliness does not neutralize erotic charge. Even alone, the shower remains a threshold. Nothing begins. Nothing ends. Desire circulates without destination.

Bathrooms in the 1970s and 1980s: Keith Haring and release

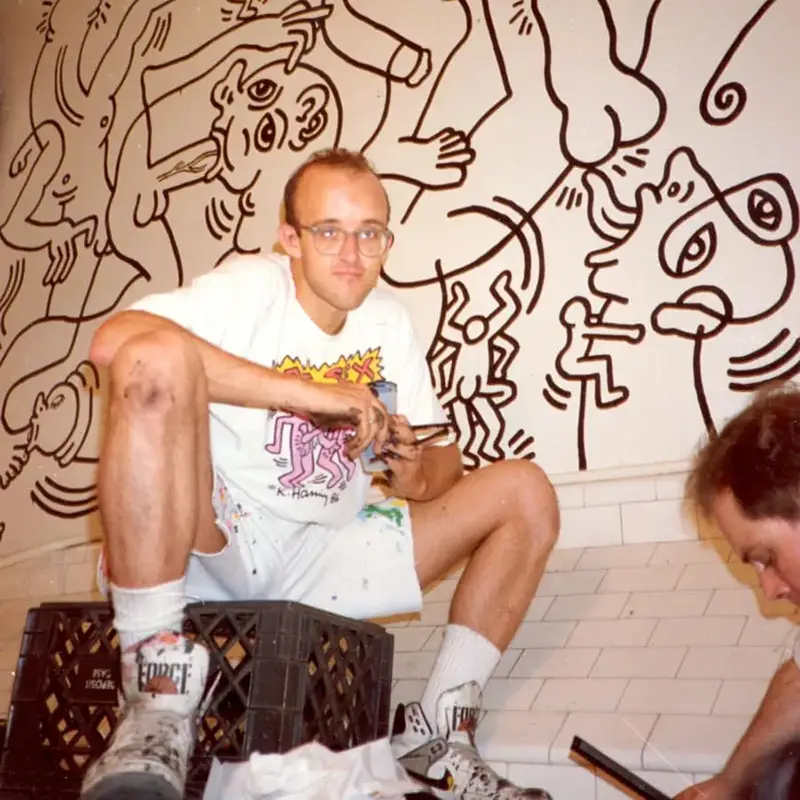

If Cadmus compresses desire, Keith Haring detonates it. In late 1970s and 1980s New York, public bathrooms – subway stations, cultural centers, restrooms – become sites where repression briefly collapses.

Haring’s walls are flooded with explicit symbols. Phalluses repeat obsessively. Bodies couple, penetrate, multiply. Sex is not hinted at; it is asserted. These bathrooms do not conceal desire – they idolize it. They function as secular chapels devoted to male sexuality, where fellatio, anal contact and animal appetite are rendered visible. Spaces designed to be cleaned, erased and controlled are overtaken by presence. Desire finds its mecca in the places meant to eliminate it.

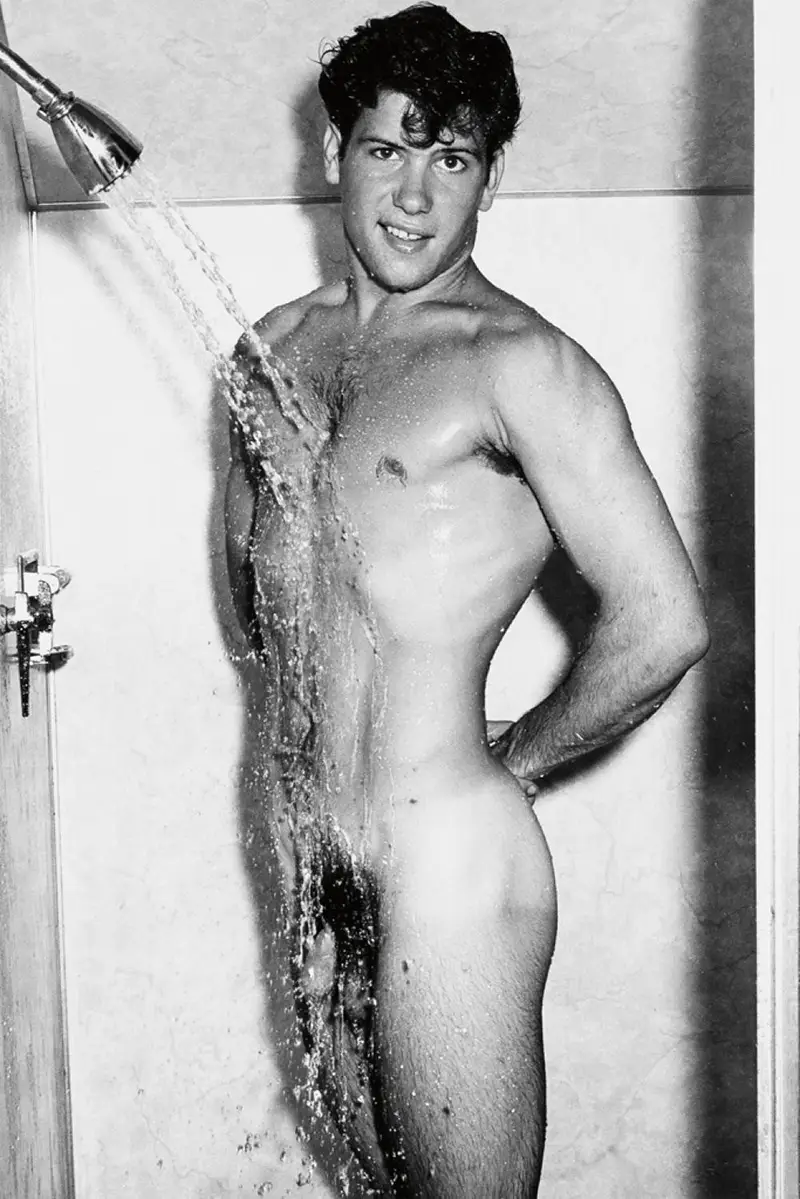

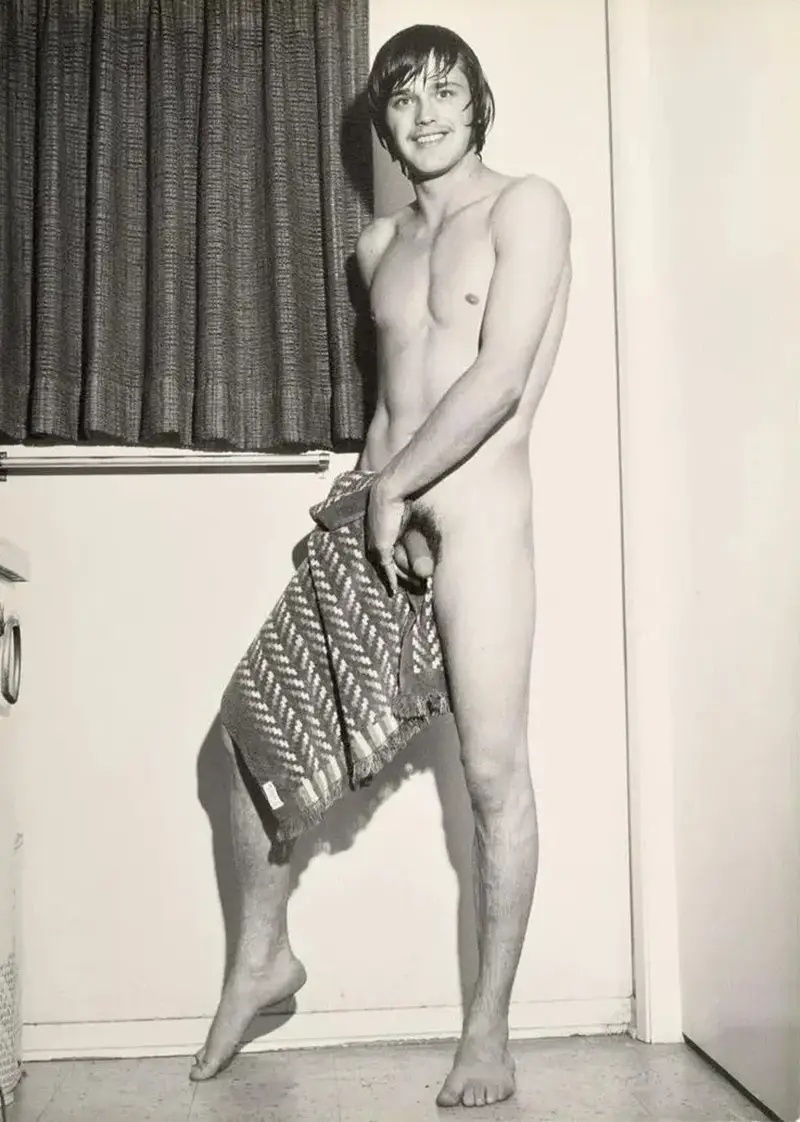

Photography and the institutional alibi

Photography exploits the same loophole. From the mid-twentieth century onward, photographers like Bruce Bellas operate inside locker rooms and showers under the guise of athletic documentation. Institutions authorize the gaze. Sport excuses nudity. Eroticism passes as routine.

Bodies are disciplined, posed, regulated – and unmistakably charged. What appears neutral is structured. Desire survives by remaining embedded in function.

The female locker room as an interior space

If the male locker room operates as a site of socialization through proximity, rivalry and discipline, its female counterpart has historically produced a different imaginary. The women’s locker room is less often framed as a collective body under pressure and more as an intimate space turned inward.

In cinema, photography and visual culture, the female changing room rarely becomes a theatre of confrontation. It is quieter, fragmented, less hierarchical. Bodies are present, but not measured against one another. Mirrors matter more than benches. Time slows rather than intensifying.

Eroticism is not absent, but structured differently. Where male desire is routed through friction and enforced closeness, female desire is often framed as a private negotiation with the self. Vulnerability replaces rivalry. Exposure remains personal rather than circulating socially.

Gendered spaces and the politics of proximity

This contrast reveals how locker rooms function as gendered devices. Male desire is allowed to exist collectively, provided it can be coded as competition, endurance or discipline. Female desire is redirected toward introspection, self-regulation and privacy.

The difference is cultural, not biological. It is produced through images, narratives and expectations layered over time. The male locker room tolerates closeness because desire can be disguised as function. The female locker room isolates the body, discouraging collective tension. Both spaces regulate sexuality. They simply do so through opposite strategies.

From controlled architectures to fashion

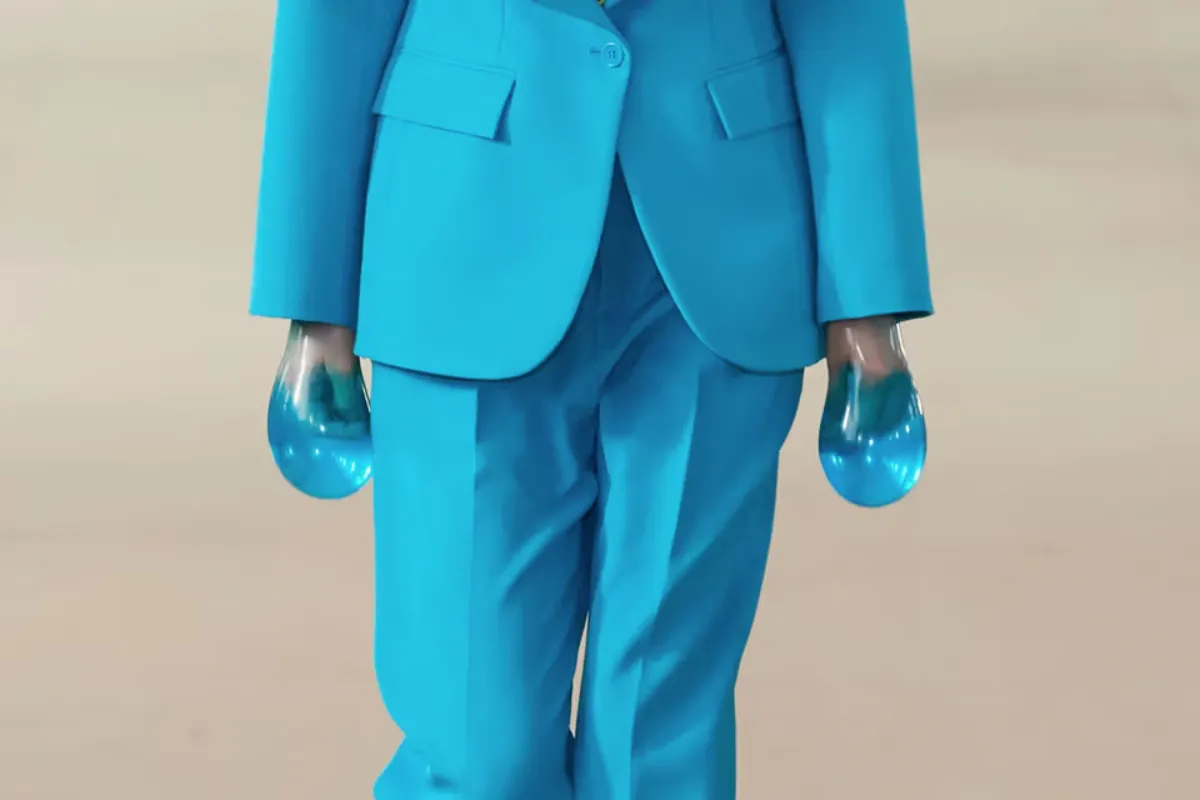

Fashion absorbs these distinctions rather than erasing them. In menswear, the locker room remains a persistent reference: uniforms, sportswear, compression, repetition. In the 1990s, Calvin Klein fixed the locker room as a visual standard – institutional, clean, disciplined. Dsquared2 exaggerated its theatricality, amplifying bodies and hierarchy without dissolving rivalry.

More recent designers slow the image down. Ludovic de Saint Sernin allows fabric to linger where uniforms usually move on, exposing hesitation rather than performance. Willy Chavarria reframes sportswear as a collective body, heavy and political, stripped of triumph and individual heroism. In these approaches, masculinity is no longer resolved through victory, but through endurance.

In womenswear, references to backstage, changing rooms and preparation spaces tend to emphasize interiority. The body is framed in relation to itself rather than to others. Exposure is not competitive but introspective. The architectural logic remains, but its symbolic function shifts. Here, endurance replaces spectacle. Sustainability aligns with repetition, pressure and use. Clothes, like bodies, are imagined to withstand contact rather than display.

Heated rivalry as a gendered historical condition

Across painting, cinema, photography and fashion, locker rooms, showers and bathrooms function as containers for desire that cannot fully declare itself. For men, these environments produce closeness without intimacy, exposure without acknowledgment. For women, they generate solitude within exposure, intimacy without collectivity.

Heated rivalry is not universal. It is a specifically masculine condition, shaped by architectures that keep bodies together while refusing interpretation. Desire is neither liberated nor eliminated. It is managed. These spaces are dirty, disciplined, unfinished. They do not resolve sexuality; they organize it. And in doing so, they reveal how much of desire depends not on what is shown, but on where it is allowed to exist.

Ario Mezzolani