Maria Luisa Frisa and the political value of fashion

Fashion needs a political message: activism, disruption, obsession – fashion is no longer just a creative matter. The responses of Maria Luisa Frisa

Interview with Maria Luisa Frisa: global fashion scenario, the creative effort and the management

Maria Luisa Frisa: I was asked to put together a selection of stories about fashion. I chose by era, by writing style—fiction, essays, journalism. I wanted to convey the complexity of fashion. Bret Easton Ellis allowed me to reference fashion imaginaries – like Steven Meisel’s covers for Vogue Italia, in the 1990s. Since fashion became a global system, there are creative voices both in design studios and in communication offices. It seems like everyone must be listened to. There is no longer a fashion world that exists within a coherent system. You have to satisfy sensitivities and cultures that coexist in what has become a global vision. Within major groups, a reassessment is needed regarding the multitude of roles that claim the right to speak.

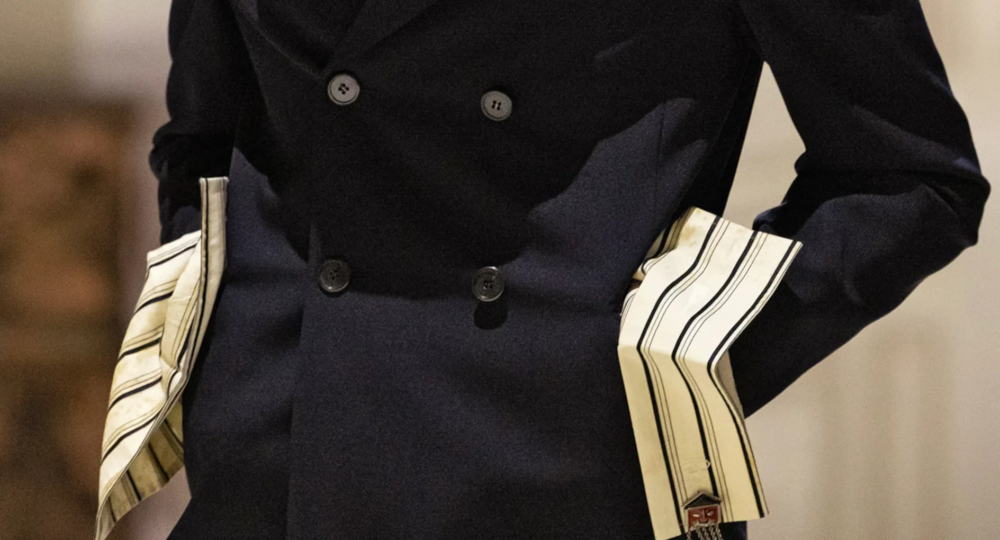

Chanel’s president of fashion, after the Cruise show in Como, said that the Chanel house is strong regardless of who designs its fashion line. What endures is the consistency of the brand, not a demiurgic creative director. Fashion made a mistake: it never imagined that exponential growth could come to a halt.

Carlo Mazzoni: Who should have more of a voice, the creative lead or the managerial officer?

Maria Luisa Frisa: The creative lead. I cited Chanel’s president of fashion as an example I disagree with. The creative must design something we didn’t know we wanted—not just black trousers every season. Alessandro Michele at Gucci imagined something that didn’t yet exist and that we realized we desired.

The responsibility of creativity and nostalgia: Armani, Prada, Gucci, and Maria Grazia Chiuri

Carlo Mazzoni: Responsibility still lies with creatives—for better or worse. They must challenge the supply chains, pushing for less synthetics, less elastane, less polyurethane. Creativity that requires plastic or synthetic materials is nostalgia for the past. There’s no need to even mention sustainability—a word that’s been overused. Creativity only exists if it operates within a context of discipline. Anything else is veiled nostalgia. Creativity without discipline is nostalgia.

Maria Luisa Frisa: Armani and Hermès are about style, not about fashion. Prada is a fashion topic—the only fashion company that is thriving, thanks to Miu Miu. Prada’s ungraceful gaze. A designer like Raf Simons. The biggest mistake Gucci made was thinking it needed to return to a classicism that Gucci never actually had. What is Gucci’s classicism? Maybe Tom Ford’s erotic interpretation of a brand that was never truly erotic? If Monsieur Pinault decided one day to move Gucci’s archive to Paris, no one could object. Same with Valentino’s archive, which is owned by Mayhoola. If these owners decided to house the archives in their private palaces, we couldn’t stop them.

Maria Luisa Frisa, an interview: Italian fashion, messaging, activism – from Alessandro Michele to Duran Lantink

Carlo Mazzoni: Don’t you agree today fashion needs a message that can reach the community, a positive message about society? Something that involves people regardless of whether they buy the clothes or not?

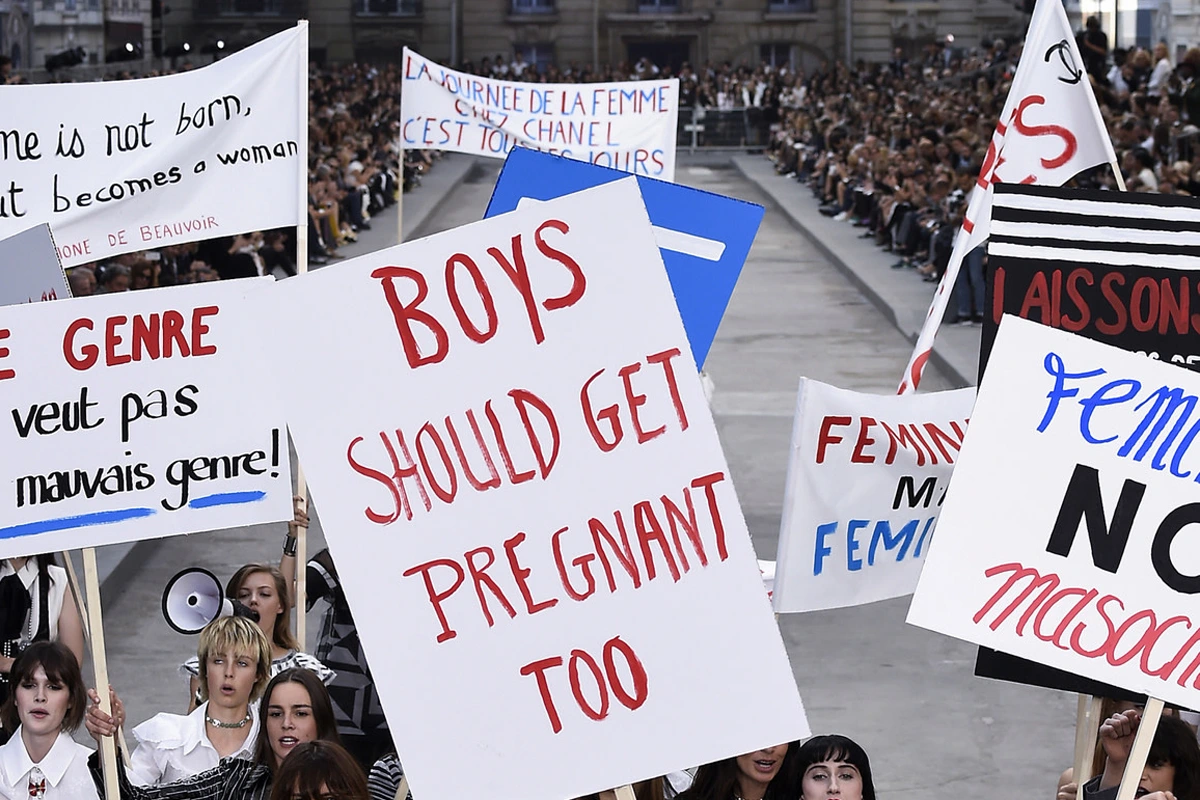

Maria Luisa Frisa: I’ve worked on Italian fashion; I’ve curated exhibitions because I wanted to reconstruct the history and the value. A cultural and productive system—a political value as well. In Italy, this isn’t understood. Then there’s creative and sociological expression: Alessandro Michele rejected the idea of the new at all costs, because fashion renews itself by looking at its past. Maria Grazia Chiuri introduced feminism.

Carlo Mazzoni: In 2015, when Alessandro Michele was at Gucci, we lived in the bubble of Instagram, of social media, of self-indulgence, selfies, vanity, clothes worn to be photographed outside fashion shows. Chiuri came out with almost political activism. Today, after Covid, after a war, with Trump in America, with the downfall of social media’s reputation—we need what Chiuri did ten years ago.

Maria Luisa Frisa: Chiuri was the first female creative director of a house always led by men. The men at Dior had defined a certain idea of femininity. Chiuri reintroduced the work of Chimamanda—no one knew her at the time. That cry: We should all be feminists.

Carlo Mazzoni: In 2025, activism and politics – politics as in the ancient Greek sense, the relationship between citizens—is what fashion needs. To use a perhaps simplistic example: two years ago, when war broke out between Russia and Ukraine, Demna sent soldiers down the runway.

Maria Luisa Frisa: Vivienne Westwood was a disruptive and activist figure. In terms of personality, one could also describe McQueen as militant—focused on his personal suffering. Today, we have campaigns instead of analysis. Some take a stand, others voice personal opinions, some make proclamations without having the authority—but no one offers true analysis. Young people lack focus; they’re hypnotized, anesthetized by endless scrolling. On the other side, fashion media only seeks to be pleasing.

Carlo Mazzoni: Duran Lantink, last February. Applause for his tailoring skill, audacity, vision, and consistency—yes—but it was a creativity built on plastic volumes. With PR and networking in full activation.

Maria Luisa Frisa: I wanted to showcase a piece by Duran Lantink, but the company wanted to sell it—they wouldn’t lend it. The exhibition was in a public museum, funded with institutional money—we couldn’t buy it.

Maria Luisa Frisa, IUAV, and the Veneto: politics, the university – top students and the obsessed

Carlo Mazzoni: The Veneto region is perhaps the leading manufacturing district for experimental weaving, also thanks to its proximity to IUAV, where you are part of the scientific board. In Veneto, there are also attempts to revive the hemp supply chain, which could be a pragmatic and concrete driver for rebuilding a national fashion system.

Maria Luisa Frisa: I tried speaking with politicians at the helm of the Italian university and research, arguing that if we don’t give dignity to fashion studies within universities, we won’t get anywhere. I never managed to achieve anything. Universities should catalyze the consolidation of an academic discipline. My best students left the country because I couldn’t help them find jobs in Italy. There are exceptions like Stefano Gallici, Pasqualetti, Marco Rambaldi, who launched their own brands.

The best students are willing to do anything. I realized it while preparing exhibitions—I was teaching curatorial practices in fashion. The best students are those who understand the value of education. They told me: “The chance to see the clothes in person, to understand how they’re constructed—when will I ever get that again?”

Carlo Mazzoni: To work in fashion, you need to be obsessed. Are your students more obsessed with manufacturing—how to cut, sew—or more with image, identifying a photographer rather than a stylist?

Maria Luisa Frisa: One of our students was Giovanni Dario Laudicina. When he started the course, I sent him to Judith Clark’s studio in London. Giovanni was sleeping on the floor of Judith’s studio with Francesco Casarotto, another of our students, just to be in that environment. They were interested in image. Then there are those who care about the project—making a collection. We don’t train tailors—we train designers.

I was a terrible student myself. I even dropped out for a while. I came to university late, through strange paths, eventually becoming a professor. Universities are places where communities are formed, people with shared passion. Especially in a public school like Venice’s: there are those doing theater, architecture, art. These communities include us professors too. The boundary between student and teacher is thin. I don’t believe in the friendly professor. I always use formal address with my students. It doesn’t mean I care less—it’s a formal distance that allows for precision.

Carlo Mazzoni