A Sixties villa show the rough character of Atlantic France

Far from the clichés of the Côte d’Azur, a house becomes a stage for reinvention. In the windswept Basque town of Saint-Jean-de-Luz, Marie Schuller captures her mother in her house

Marie Schuller’s mother: the house on the Atlantic coast

Marie Schuller: Mother bought a house in the South of France. The stormy Atlantic side, not the Cote d’Azur. She got the keys a few days before lockdown, leading to an unexpected four months in total solitude, armed with nothing but a small suitcase of weather inappropriate clothing. The house is large, abandoned, gutted of its interiors apart from the remains of the quaint Sixties decor throughout. It’s an eerie ghostly place with its heyday placed in the past. Someone must have been proud of those candy colored bathroom suites a long time ago. Two Dobermans who at one point guarded the residence have shredded the patterned fabric wallpaper into pieces.

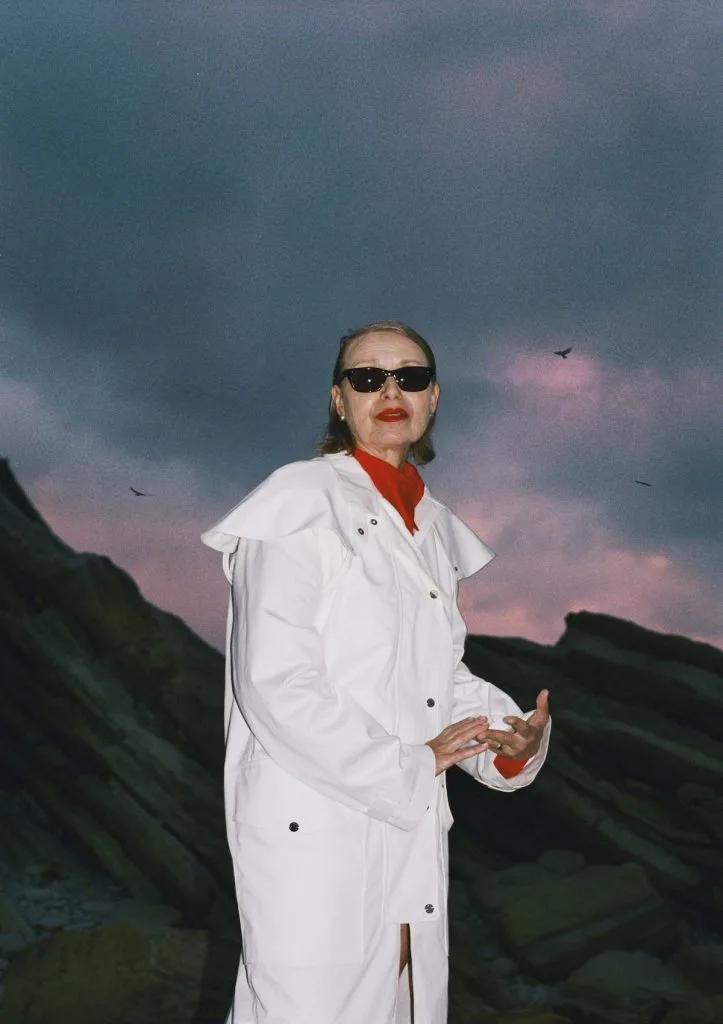

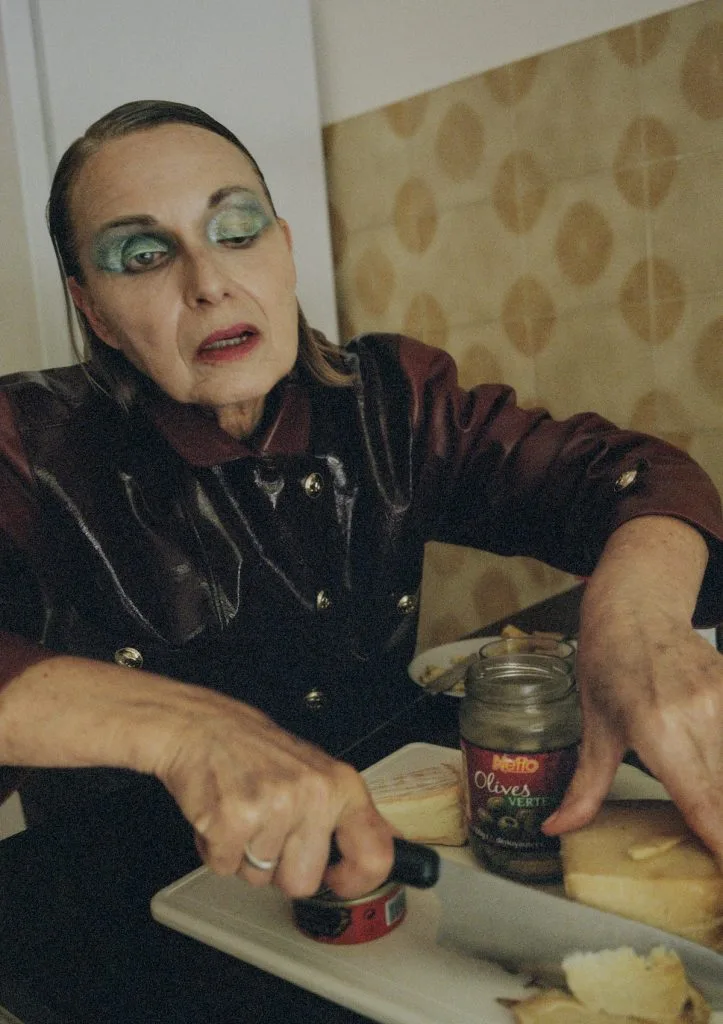

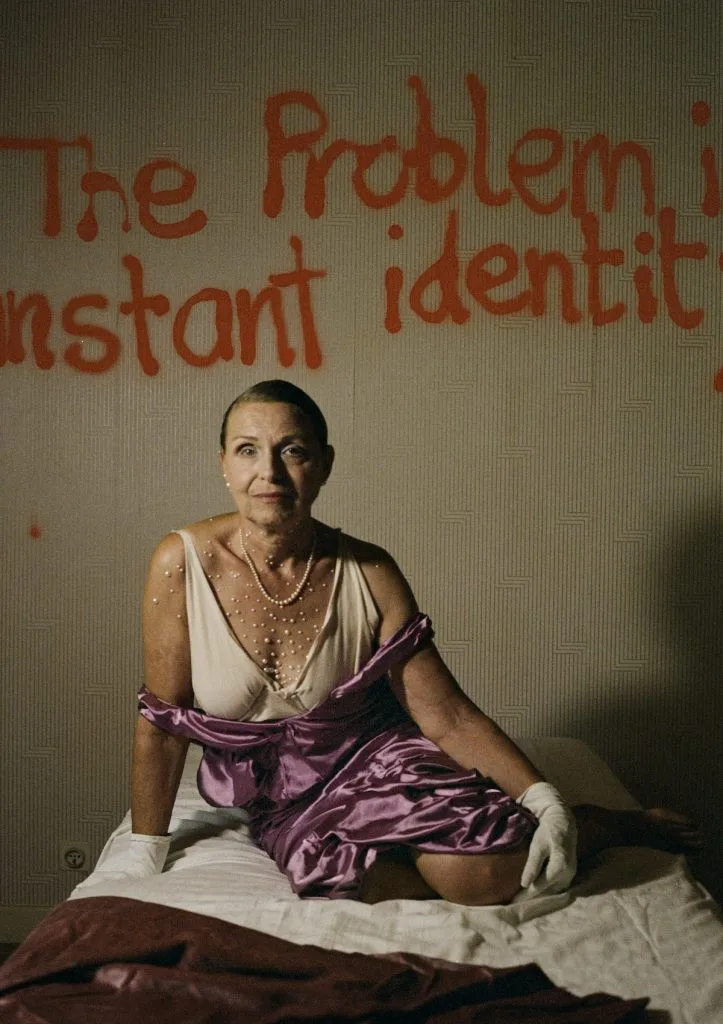

Some heavy furniture left faded markings on the old carpet, creating an imprint of the house’s former interior. There’s a fire pit in the garden with the charred remains of things that look mildly suspicious. The house is ready to be stripped back, destroyed, renewed and rebuilt. To our surprise my mother loved being alone in the house. She made friends with a nest of newly hatched birds (who all died with the first summer storm), and a deranged old cat (who survived so far), and doesn’t seem to miss us, or human beings in general. Once the lockdown eased, I went to see her and photograph her. We started making images around her new house, playing around and generally hanging out with not much of a plan. But these documentary-driven pictures are mixed with performative images, using fashion as a transformative energy that rendered my mother into various characters far removed from her real self. She became the witch in the creepy house, the cougar, the mafia heiress and the Hitchcock heroine.

The other South of France: Atlantic, wild, and resistant to cliché

The South of France most people picture lies on the Mediterranean—fields of lavender, pastel villages, bougainvillea, rosé. But the south-western coast, where Saint-Jean-de-Luz stretches toward the Spanish border, tells a different story. It’s a coast of relentless waves, dense pine forests, long beaches with no shelter, and skies that turn from clear to slate in a matter of minutes. The air is heavy with salt and wetness. Here, the idea of escape is not glamorous—it’s elemental.

This is France’s Atlantic façade, a place often left out of the postcard narrative. It is not softened for tourism, not staged for the international gaze. People come here to surf, to walk alone on wide empty beaches, or to live quietly between the land and the sea. Nature is not decorative—it is dominant.

Saint-Jean-de-Luz: a town suspended between fishing port, monarchy, and Basque soul

Set in the Basque Country, Saint-Jean-de-Luz is shaped by contradiction. A town that once hosted the royal wedding of Louis XIV and Maria Theresa of Spain in 1660, it has none of the pomp its history might suggest. The fishing port still defines the town’s rhythm more than its historical plaques. The architecture is utilitarian, solid—red beams, white stucco, stone under heavy roofs. No frivolity. No gloss.

The Basque identity is not just visible here—it is structural. It informs how the town looks, speaks, eats, and refuses to be simplified. Even the landscape resists. The coastline is unsheltered and alive, constantly reshaped by the Atlantic. It doesn’t suggest stillness or surrender, but endurance.

A perfect setting for withdrawal: houses that hold stories, not spectacle

It makes perfect sense that this would be the place where someone could disappear, quietly and without ceremony. A house like the one Schuller describes—abandoned, outdated, even unsettling—doesn’t clash with its surroundings. In this part of France, architectural decay doesn’t read as failure. It becomes part of the terrain.

The region is full of such houses: once-proud holiday homes from the 1960s and ’70s, now faded and water-stained, neither luxurious nor ruinous. They are stubbornly unpicturesque, and because of this, they hold space for ambiguity. They don’t perform a narrative. They leave room for one.

Schuller’s mother settling into such a place—befriending birds and a half-mad cat, drifting into roles for the camera—is not eccentric. It fits. It reflects the rawness of the landscape, the openness of the town’s margins, and the possibility of transformation not as performance, but as a form of survival.

Editorial Team