From Ukraine. Two million stories to begin to understand the war

Mediterranea Saving Humans activated right after the Russian invasion. Always standing by the civilian population – the only real victims

Med Care 4 Ukraine: one year anniversary

Lviv, August 2023. «We have been doing this for one year now» says Caterina Rigo, activist on location for Mediterranea during this mission. One year of going back and forth from Ukraine, bringing medical care to refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs). Mediterranea Saving Humans took action right away, after the outbreak of the war. «At first we started with an initiative called Safe Passage», Rigo says, «to help people crossing the border with Poland and reaching other countries».

Time passed, the war evolved, and the needs of the civilian population changed. IDPs started coming to Lviv in massive numbers. Today, there are around two hundred and fifty thousand of them. Since the beginning of the war, more than two million people have passed through here. Civilians, especially in refugee camps, soon needed medical care and supplies. Mediterranea answered the call. I traveled to Lviv with one of their teams, and had the chance to observe their work from up close.

From Lviv: providing continuous healthcare in the camps.

Mediterranea provides continuous care, visiting each camp or shelter at least once every week. «The most valuable aspect is probably consistency, » Rigo explains. «People know we are coming, they know they have someone they can trust, who cares about them». Lviv had a population of seven hundred thousand residents before the war. Answering the needs of hundreds of thousands more was simply not possible. International humanitarian organizations jumped in.

Trust is also a key part of the job. «We noticed some people have little trust in local public healthcare, but a lot of them see Italian medicine as trustworthy ». Always coming on the same days and at the same time also helps: «It is something to wait for amid the boredom of life in the camps». Residents have close to nothing to do.

Even if they are not ill now, it is significant for them to know someone will be there in case they do. This is also key on a psychological level – most people living in the camps fled their homes without knowing if they would ever be able to go back. For both activists and the medical staff, listening is central as well. Most people have an urge to tell their stories, share their experiences.

The job of translators in this context is vital – they are mostly Lviv residents who speak English or Italian. It takes sensitivity, strength, awareness, and professionalism – and they are up for the task.

Adaptation: Mediterranea from Safe Passage to Med Care

«After the outbreak of the war we wanted to help the civilian population, » says Rigo. At the time, the emergency was taking people out of the country. Mediterranea observed one need especially: helping people who were struggling to get out of the country: «From the beginning, the aim was guaranteeing a passage that was free and secure for the whole population, without discrimination».

Many organizations, they found, were making people pay for the journey. «There was a lot of empathy, but also some contradictions», Rigo recalls. They made a first trip stopping in Lviv, and then reached Kyiv with a second mission. It was not merely about the current emergency, but also about the future of the people they were helping. «We were in touch with people and organizations in Venice, Naples, Rome, Milan and other cities – to make sure the people we were bringing to Italy would be welcomed and integrated properly».

Rescue first, discuss later: Mediterranea and the hypocrisy of passports

«Our aim, » she explains, «was to bring everyone, challenging the hypocrisy of the passport and tearing down every barrier». This meant giving special help to people who did not have a Ukrainian passport, but also transexual people who had not completed their transition, «which we did co-operating with the NGO Insight as well». Often the lines were blurry, and people were unfairly endangered as a result.

«One of the people we brought back was an Italian citizen who also has a Ukrainian passport – he has been working in Italy for years and is a resident of a small town in northern Italy». He was in Ukraine for a few days to attend his father’s funeral when the war started. On his way home to Italy, he was denied an exit visa. Mediterranea, with the help of the Italian embassy, managed to get him back.

All too often, passports become pieces of paper that decide who can or cannot cross a border. «What I love about Mediterranea is that we see humans simply as humans». One of their slogans is «Rescue first, discuss later». Politics and discrimination should not determine whose life gets to be saved.

Starting Med Care 4 Ukraine: changing needs

After a while, priorities changed. Many people wanted to stay in the country – the majority wished to go back to their lives once the war was over. Many women whose men are on the front also want to stay close and support them. Needs have changed too. In Lviv there were not enough staff and medicines to take care of all those who were arriving.

Once again, Mediterranea jumped in – creating Med Care 4 Ukraine. August marked the one-year anniversary of providing continuous care to all those in need – from IDPs to homeless and single mothers. In August they achieved one more goal too: as of today, they have taken charge of more than one thousand patients. It is about providing healthcare, but it is also a political stand. «We are against every kind of war, all across the globe», Caterina says. They are consistent in their action too: «Mediterranea always stands on the side of civilians – who are always the only true victims of wars, whose stories are often disregarded». They do the same job at sea too, saving humans in the Mediterranean.

Here in Ukraine, explains operations coordinator Denny Castiglione, «we are probably the only organization who not only visit patients, but also distribute the medicines people need completely free of charge». It is a political stand too: «how could someone who has lost everything they owned afford medicines? ».

The issue of corruption must also be factored in. The Ukrainian healthcare system was already corrupted, but it got worse since the war. Castiglione is also responsible for the safety of volunteers, remaining available and in touch with authorities 24/7 in case something happens.

[envira-gallery id=”133049″]

Sykhiv, the only institutional camp

Here in Lviv, Mediterranea regularly operates in at least eight locations. Among those, Sykhiv is the only institutional camp recognized and dealt with by the local administration. All the other camps are informal, opened because the people needing a shelter after escaping far exceeded Sykhiv’s capacity.

Sykhiv was also the first camp Mediterranea started operating in. It is a modular camp which consists of small rooms created inside big containers. It is now home to around eight hundred people. Most of them come from the eastern Russian-speaking regions: from Donetsk, Lugansk, Zaporizzja and Kherson. People are keen to tell their stories, most have an urge to do so. Rigo, who speaks the language, helps me translate, so that I can talk to them.

Real people, real stories – talking to refugees in the camp

Valentina is seventy-seven, from Bakhmut. She lost a leg in January because she was hit by a missile fragment. She had been out for five minutes when the missile hit her home and burned it to the ground. She was taken to Lviv where she underwent surgery. Today, she lives in two square meters in the camp. Her son, in his thirties, is fighting on the front, and her daughter was in Greece at the beginning of the war; now she has come back to support her.

She says she’s lucky – she lost a leg, but she is still alive. She has bright, light blue eyes – in her voice, her manner, a strength words cannot describe. Axana also comes from the east. She is a young woman and has three kids and lives in the camp with them and her husband. They traveled here by train a year ago and have lived here since. Her youngest is sick, and she invites us into the small room they all share to see him.

Vira is from Donetsk. She has Alzheimer’s. She comes to the doctors with her son, and her grandson is fighting on the front – on the Russian side. One of many stories of separated families.

Svetlana also has a child on the front, on the Ukrainian side. She came here last March with her mother, who died in the camp one year ago.

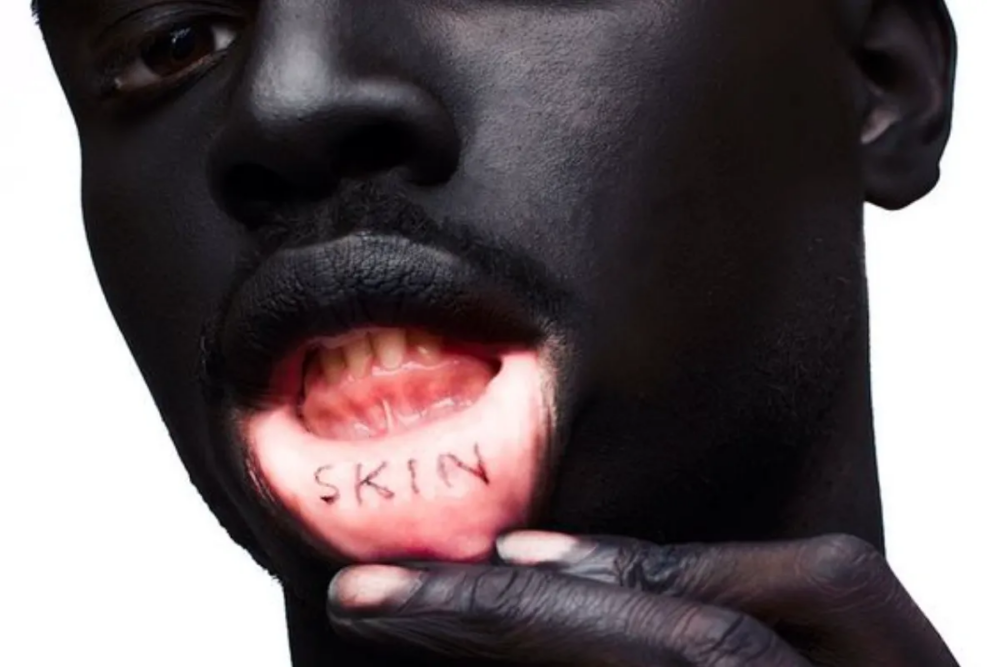

Ana has depression. She is claustrophobic because of the tight spaces in the camp, and has severe anxiety. She is clearly very happy and grateful that someone is taking care of her. Even though Lviv is a relatively quiet place compared to the rest of the country, and the war is not always immediately visible, these stories are hard to hear, as real as can be. Irrefutable proof that, when it comes to war, civilians are the only real victims. They bear the direct, heartbreaking consequences of the geopolitical agenda on their skin.

Stryiskyi, two gyms, turned into a camp

The second camp we visit is inside Stryiskyi park. The camp, set up immediately after the beginning of the war, was also used as one of the sets for the video for the popular song ‘Stefania’ by Klaush Orchestra. It is run by the local polytechnic, and located in a university park in a sports complex. Here, refugees live in big rooms with fifty to sixty beds placed next to each other.

The only partitions, where present, are made from cloth and curtains. Mediterranea visits at least twice a week. Here we meet Boris Babenko, 83, from Zaporizzja, who used to work as a musician and music teacher. When he sees us coming, he insists on changing into traditional clothes and playing for us. He has four daughters, who decided to remain closer to where they were born.

The first two patients are a couple – they were tortured on the frontline, they have cigarette marks on their skin, they’re in pain, they can’t sleep. An eleven-year-old girl comes to the doctors alone. She’s feeling sick. She lost both her parents in an attack in July. She lives with her grandmother and has an older brother and sister.

Stryiskyi administration will soon clear people out

Conditions are far from good, depression is widespread. Nonetheless, this is all people living here have left, and they look after it and after each other with care. Next week, students will be back, and the administration has decided to vacate the gyms, clearing people out. The refugees I talk to are beyond shaken.

They will be relocated outside the city, to a village a hundred kilometers away, with no services, unsure whether their children will be able to attend school and whether they will be able to access healthcare and the medicines they need – far from humanitarian help, mostly located in the city center, as well. Those who have managed to find a job will be forced to leave it.

There are only two buses a day – and they cost the equivalent of five euros (an average meal in a café is around two). They ask me to report on this, to take pictures and tell their stories, with what little faith they still have in the media. I know there is not much I can do – I can listen, I can bear witness to the injustice, to these people being punished, these people who already lost everything, who are always at the bottom.

I can say they come from places we learned the names of in the past year and a half because of the moving front and battlefields. We often forget these names once meant home for thousands of people – a simple house, a school, a hospital, and a cafeteria just like the ones we know. Now, those names sound to them like loss and destruction. Yet, there is so much life, dignity, and kindness, even gratitude left in them.

Mediterranea acts: no time for stalling

In the face of all this suffering and injustice, in the face of wars and migrations, of denied rights, there is no time for stalling. Mediterranea, at its core, is a group of people acting rather than doing nothing. In the age of apathy, action is all that can save us, on the land, and at sea. No time for discussions, theories, or doubts, in front of pressing human needs. When it comes to human lives, it is all just about that: save first, discuss later.

Mediterranea

Established in the summer of 2018 out of indignation at the thousands of deaths in the Mediterranean and the policy of closed ports. From the union of people and associations, the civil society platform organized, and in a short time they put the first and, still only, Italian-flagged civil rescue vessel at sea.

With the escalation of international tensions and Italian and European migration policies, Mediterranea went to assist migrants in danger along the most frequented routes by also organizing land missions both on the Balkan Route and in Ukraine.