Milan, from Rationalism to the Neo Ratio of Material

A Milanese attitude, an identity for the city of Milan: from Rationalism to the exposed engineering of the Torre Velasca, to new materials – questions and answers

The Milanese attitude: from Piazza Meda to Piazza San Babila

A cultural and intellectual challenge I’d like to continue writing about, poised between seriousness and irony, between delirium and reason: to define an aesthetic identity of Milan. The game of describing a way, a taste, a style that is precisely Milanese—without overusing the word “Milanese.” Finding a balance, a pace—an identity-based attitude that can synthesize the city of Milan.

Piazza Meda is a compendium of Milanese architecture: Piero Portaluppi, Pier Luigi Magistretti, Gio Ponti, and the Chase Manhattan Bank by the BBPR studio firm. In the center stands the Pomodoro’s Sun, surrounded by a few magnolia trees, which are native to this region. Piazza Meda is a starting point, a kickoff, to search for a genuine Milanese measure.

People often say that Milan is not beautiful. Compared to Rome, Florence, or Venice—those other grand dames—Milan comes across as a functional, commercial hub rather than an aesthetic one. Yet that cliché dissolves the moment Milan is presented as the capital of modernist architecture.

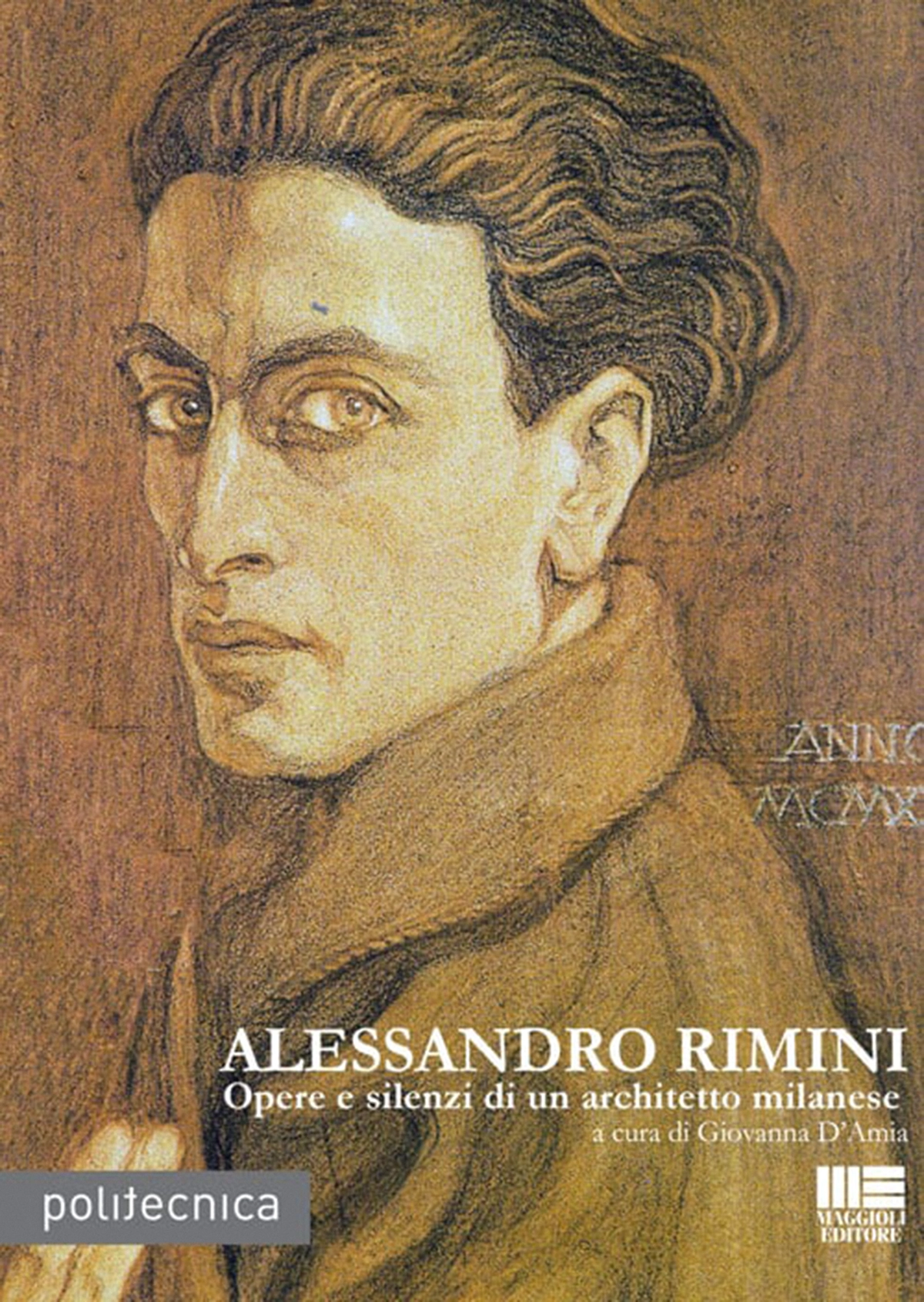

From Piazza Meda, one heads to Piazza San Babila: the buildings designed by Alessandro Rimini, based on grids and modulations. The Rubanuvole, in English the Clouds Stealer – formally known as the Snia Viscosa tower – rises front and center. The intense traffic swirling around Piazza San Babila lends it a prominence too conspicuous for it to serve as a stylistic manifesto.

The Italian Rationalism, Terragni’s Casa del Fascio in Como, and BBPR’s Torre Velasca

In a broader cultural view, the Milanese measure draws its roots from the evolution of mid-20th-century Italian Rationalism. This Rationalism pursued a purity of design, as if a building could paraphrase the molecular construction of carbon—a crystal in architecture—when every angle and distance is respected, and geometry becomes the primary structural rule. One prime expression of this is Terragni’s Casa del Fascio in Como. My “game” begins here, on how Italian Rationalism evolved in Milan after the 1950s.

My next move landed on the Torre Velasca (completed around 1955). The BBPR firm—particularly Ernesto Nathan Rogers, architectural theorist and editor of Casabella—wanted to go beyond the codes of Italian Rationalism, seeking a measure peculiar to Milan. A first glimpse is found in the disordered alternation of solids and voids in Torre Velasca, which breaks the symmetry of Rationalist masonry. Going further, Rogers introduced cultural references—history, tradition, local territory. The aesthetic, the beauty of Milan, is denser, less pristine, wrapped in a cultural blend of urban reality that is prolific, industrious.

The Torre Velasca and the Filarete Tower – BBPR, Rem Koolhaas, the Arco Lamp by Castiglioni, and Magistretti’s Eclisse

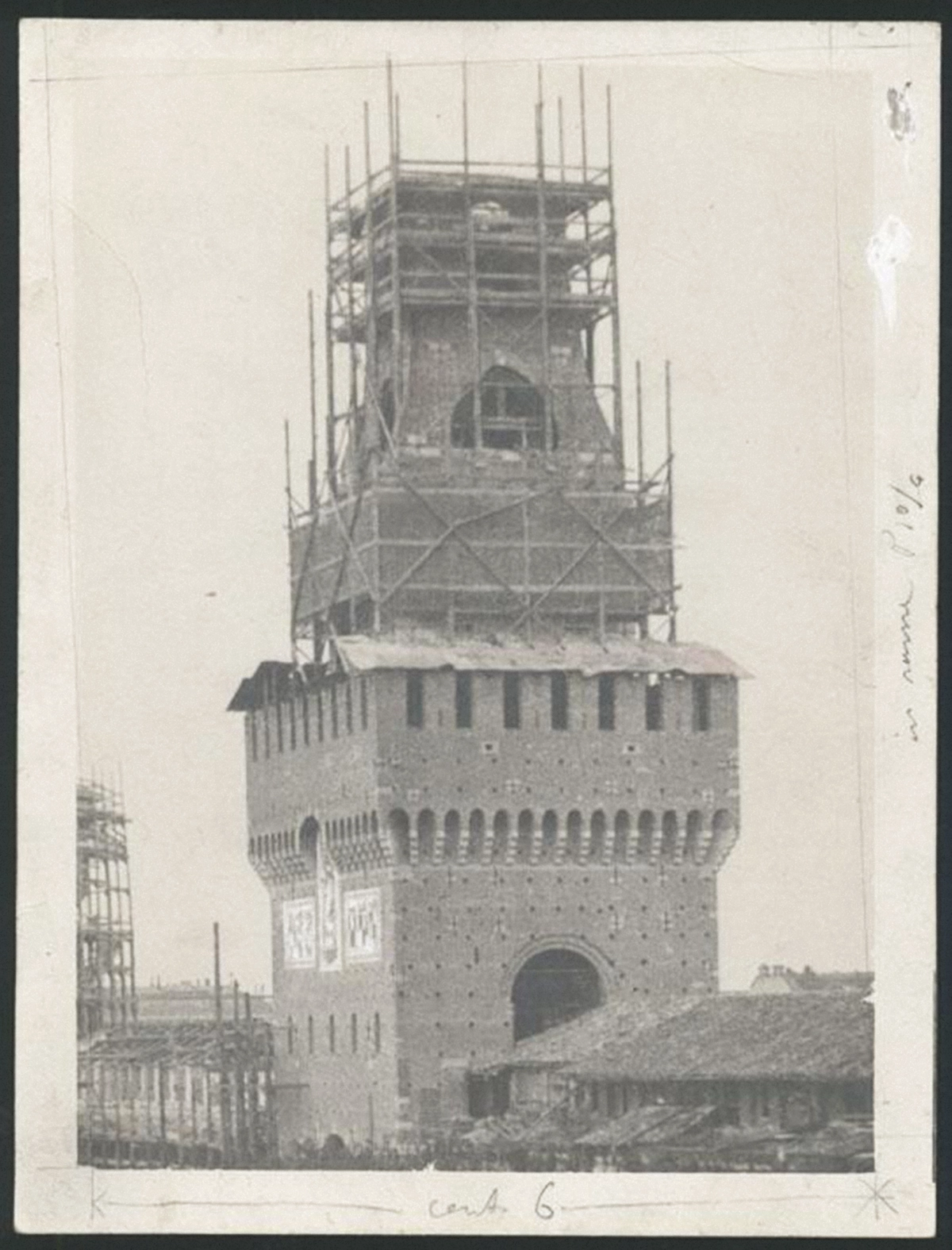

In designing the Torre Velasca, BBPR drew upon historical Milanese echoes, among them the Filarete Tower of the Sforza Castle. The diagonal beams placed from the fifteenth floor upward in the Torre Velasca are a modern reinterpretation of late-medieval buttresses and flying arches. The structure’s ribs are exposed—its engineering laid bare. Could Rem Koolhaas’s tower for the Prada Foundation be seen as a further commentary on the Torre Velasca?

Exposed engineering may be the key. Milan’s aesthetic, past and present, is based on revealing, manifesting, and expressing functional construction—essentially, engineering. We can find parallels in design: the Arco lamp by Castiglioni, designed for Flos in 1962. Its marble base weighs 65 kilograms—the minimum needed to stabilize an arc and dome that shift the lever’s fulcrum into midair. Volume and balance with weight become the rationale of the design. The design is born out of engineering, not the other way around—it is not engineering that solves the design. Another example is Vico Magistretti’s Eclisse lamp (1965)—two nested spheres that regulate light intensity. The definition of design remains the industrialization of an item—if an object requires a single screw, that screw becomes its defining feature.

A Milanese measure: the Neo Ratio and its materials, from hemp-lime to wood, to reassembled metal

Milan is the city of functional aesthetics—rich, yet unpretentious, and certainly not cold. I dare to name this Milanese measure I’m exploring: the Neo Ratio. Today, a Milanese Neo Ratio finds itself in a global context that must—and will—show respect for the supply chains of chosen materials, both in architecture and in design.

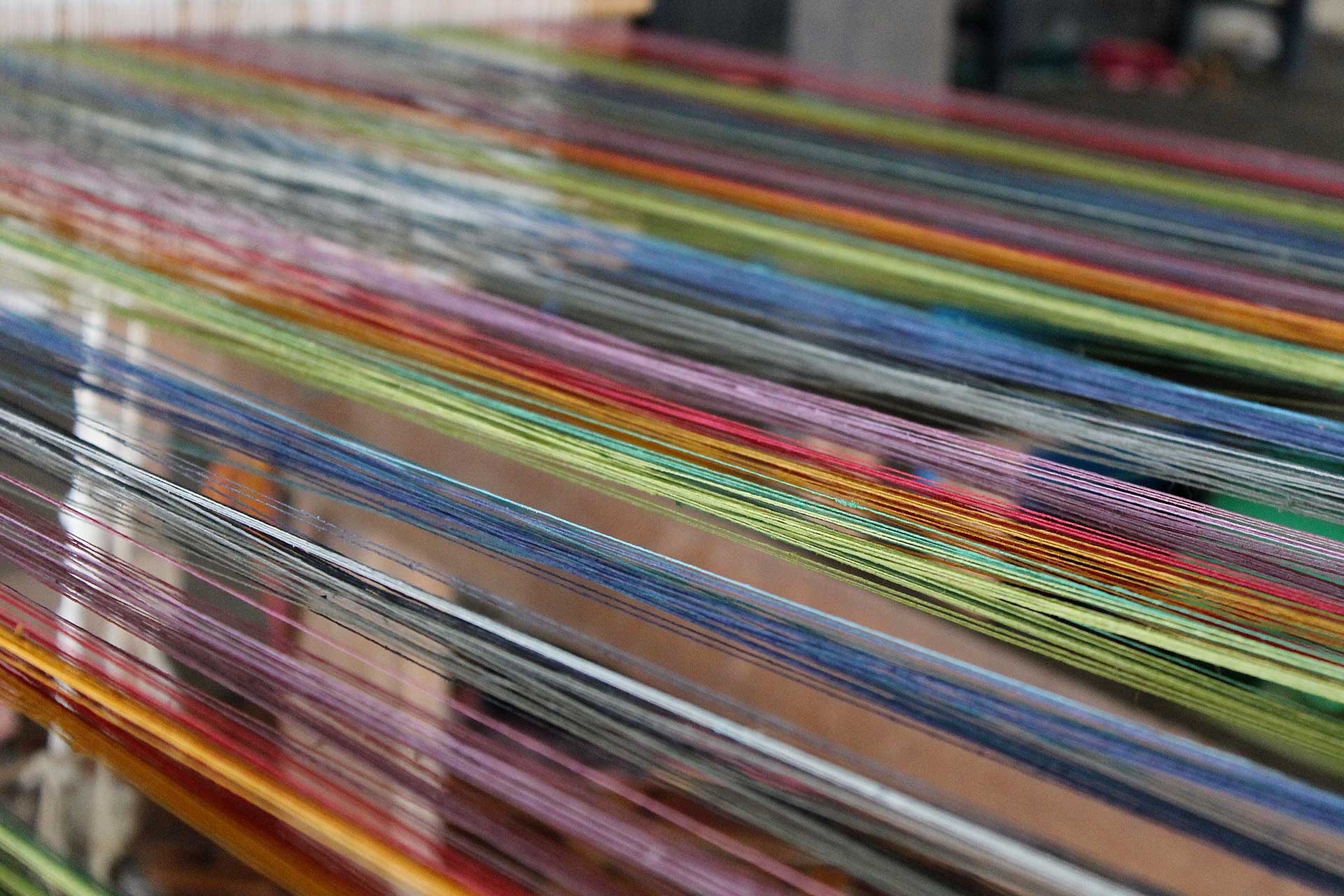

The materials of a Neo Ratio: lime generated from mixing organic matter such as agricultural byproducts and hemp. Glass that’s endlessly recyclable. Ceramic, if no synthetic materials are added—today, ceramics are used to build swimming pools: porcelain stoneware can mimic stone and marble. Yet imitation never endures; history proves this. Ceramic should be used with an appreciation for its inherent identity. Wood from controlled sources: constructing buildings and furniture in wood helps store carbon dioxide. A massive, solid walnut piece can last centuries—quite different from a walnut tree left in its natural environment.

There are two metals: iron and its alloys (steel), or aluminum (lighter, but can only be fastened with bolts, not weldable). Building with metal means acknowledging the limits of non-renewable sources—so reason must guide the design of truly lasting solutions. A piece should be forever and should be transportable, adaptable to different places. Today, everything is assembled in parts: easy to dismantle. Elements aren’t glued or welded. Now, a joint is bolted on. We are more nomadic these days, and we enjoy it. Questions no longer focus solely on recycling but also on preventing waste.

The word “trend” versus a Milanese measure, Neo Ratio, and identity-based consistency

An online shop and physical store, inustrialkonzept.com, presents a wide-ranging production in lightweight, reassemblable, bolted aluminum. We might call this production a “trend”—it has engaged established companies, emerging designers, collectives, and strategic projects—and as a trend, it partly defines the times we live in. Yet the word “trend” undercuts those who follow it. Milanese hallmarks must confront and respond to global trends, react to them. Neo Ratio: today, what earns respect is consistency of identity. Everything recognized as contemporary and timely places its identity at the forefront. Identity comes always first, before any commercial opportunity.

The difference between an architect and an interior designer

The architect is Alvar Aalto studied running water sound to design a sink. The interior designer can sometimes be a laughable affair: a mishmash—a bench with a wooden base, a polyurethane cushion, synthetic fabric printed in acrylic, metal legs that are glued together, iron screws biting into plywood. We Milanese choose the first as our guiding teacher, relegating the second to the far corner among those who still have lessons to learn.

Neo Ratio, a Milanese measure: what is Milan’s identity?

To summarize, after a flow of thoughts that some might find disjointed, I return to the initial point of my narrative. In today’s international context, in a contemporary dimension that must look to the future, what might be the attitude, the mode, the balance of a Milanese movement—an equilibrium, a way, a Neo Ratio—to define our city of Milan? A precise identity for Milan.

I don’t want to oversimplify, but I do want to hazard an answer. There are three main components. First, taking up the lesson of BBPR, Castiglioni, and Magistretti—namely, showcasing engineering and celebrating functional aesthetics – that are the foundations of early 20th-century Italian Rationalism. Second, a supply chain of materials that is as short as possible, drawing on renewable sources, without plastic and with minimal synthetic substances. Third, a reworking of Milan’s history, tradition, and territory, extending to Northern Italy and the whole country.

These three pillars, if skillfully balanced, might outline a genuine Neo Ratio—a new measure, a new rational perspective—rooted in Milan’s identity but primed for an ever-shifting global stage.