Mold: from spores to plastic, the intelligence of decay

Plastic – our most unnatural artifact – is no longer immune to the appetite of life: experimental microbial consortia are being developed that combine bacteria and fungi to attack complex plastic composites in concert

Mold in scripture and religion: ancient origins of impurity, fear, and fascination

Shame. Disgust. Death. Humanity has sought to conceal aspects of daily life – out of decorum, fear, or visceral revulsion. Mold is among them. A living organism of the fungal kingdom, mold first appears in literature in the Old Testament:

The priest is to go in and examine the mildew on the walls. If it has greenish or reddish depressions… the house is unclean. It must be torn down – its stones, timbers and all the plaster – and taken out of the town to an unclean place.

Throughout Christian tradition, mold has symbolized impurity, toxicity, even sin. It has been shunned, scrubbed away, and feared. Yet mold has also drawn fascination – both aesthetically and scientifically. Like its spores, it proliferates across disciplines, challenging our binaries of beauty and ugliness, utility and decay.

Mold as metaphor: mortality, decay, and aesthetic fascination through time

Is there beauty in mold? In looking closely, we behold an ancient, enduring organism that has outlived epochs. Frank M. Dugan, in Fungi in the Ancient World, traces how fungi – mushrooms, mildews, molds, and yeasts – helped shape early civilizations in Europe and the Near East. Mold reminds us of our mortality. As Tolstoy’s Levin remarks to Kitty in Anna Karenina:

Our whole lives are nothing but a bit of mold on the crust of a tiny planet. And yet we imagine we possess something grand – ideas, works! They are but grains of dust.

Philosophy of mold: Kant, ugliness, and the grotesque in aesthetics

The ugly, the impure, attracts. As early as 1790, Immanuel Kant addressed aesthetic responses to ugliness in his Critique of Judgment. The grotesque exists in nature and can appeal to taste – either by fascination with the corrupt or by its utility. Mold, reviled when invasive, is admired when harnessed for human benefit: in science, medicine, and gastronomy.

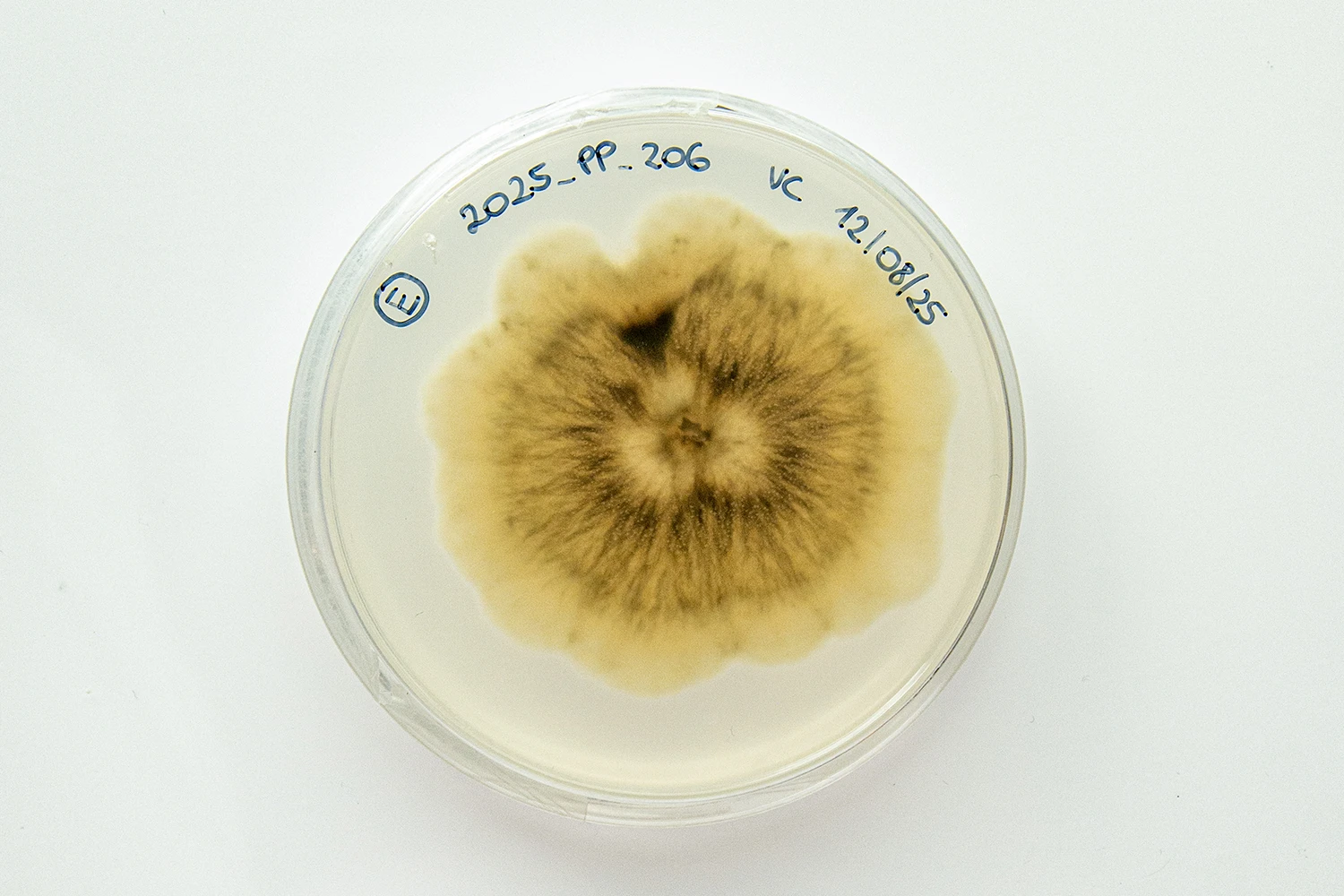

Discovery of penicillin: how mold changed the history of medicine

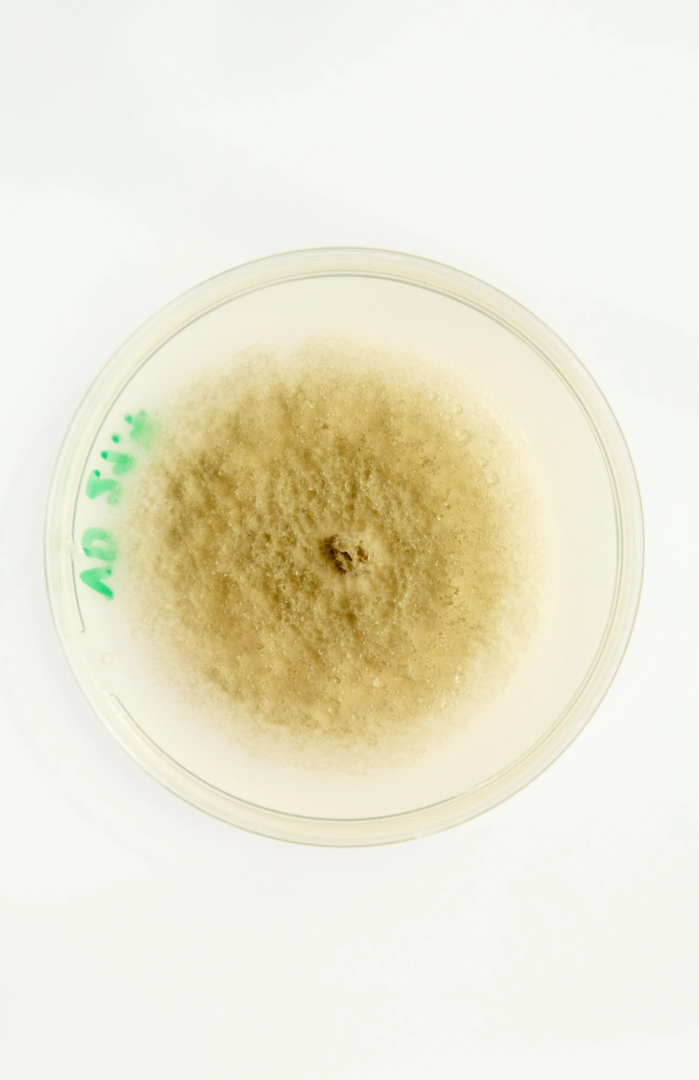

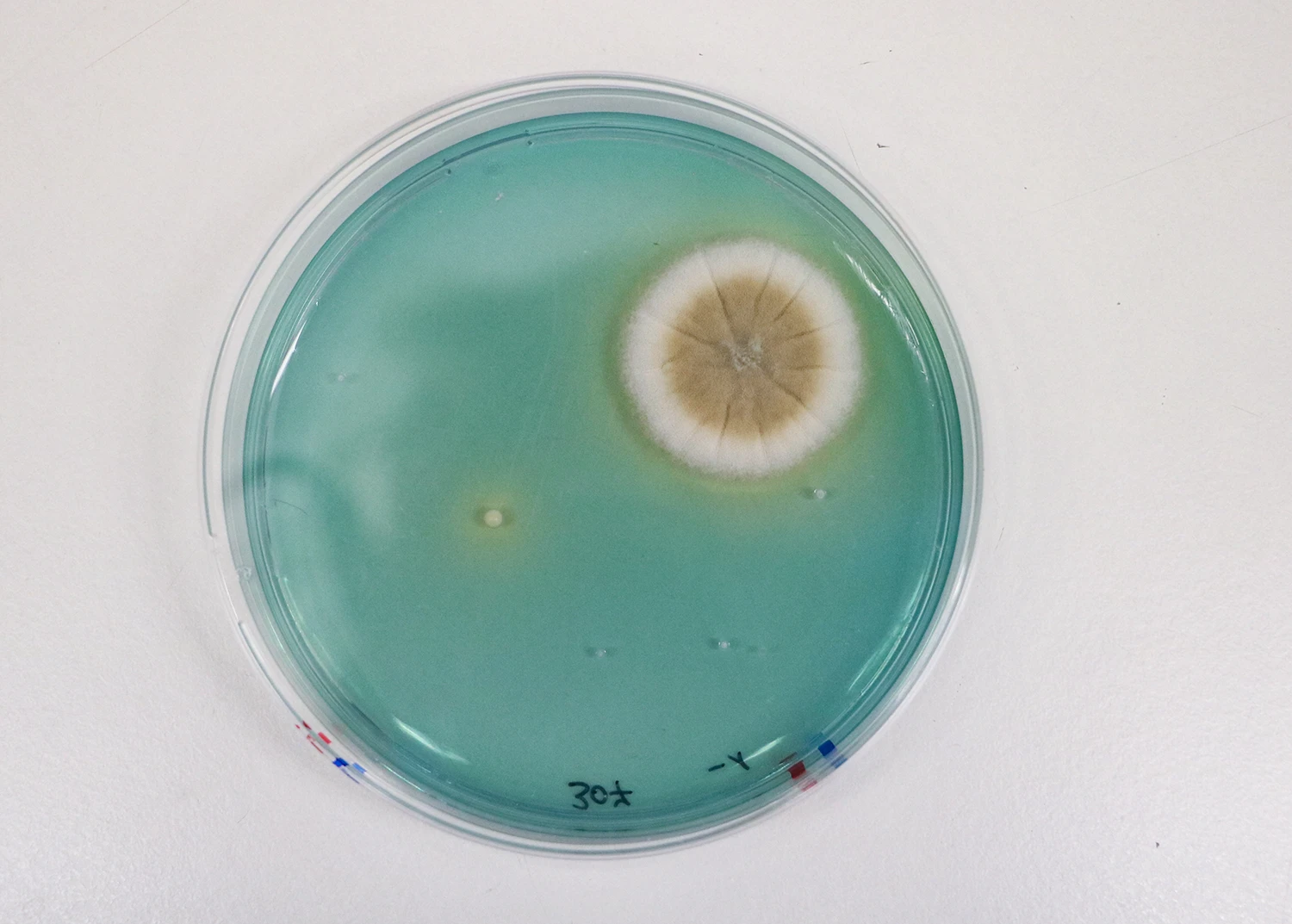

At St. Mary’s Hospital Medical School in 1928, Scottish scientist Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin by observing a green mold – Penicillium notatum – contaminating a Petri dish and killing staphylococcal bacteria. The mold secreted a substance with bactericidal properties. That substance became penicillin, later developed into a life-saving antibiotic by Howard Florey and Ernst Chain in the 1940s.

Gourmet fungi: noble molds in fine cheese and wine production

Mold not only heals; it nourishes. In cheese and wine, we speak of noble molds. Penicillium candidum creates the white rind on Brie and Camembert. Penicillium roqueforti lends blue veins to Roquefort and Gorgonzola. Botrytized wines – Tokaji from Hungary, Sauternes from France, or Germany’s Trockenbeerenauslese – rely on Botrytis cinerea, the noble rot, to concentrate sugars and deepen flavor. Here, mold becomes synonymous with taste, refinement. In the words of Nietzsche, even mold ennobles.

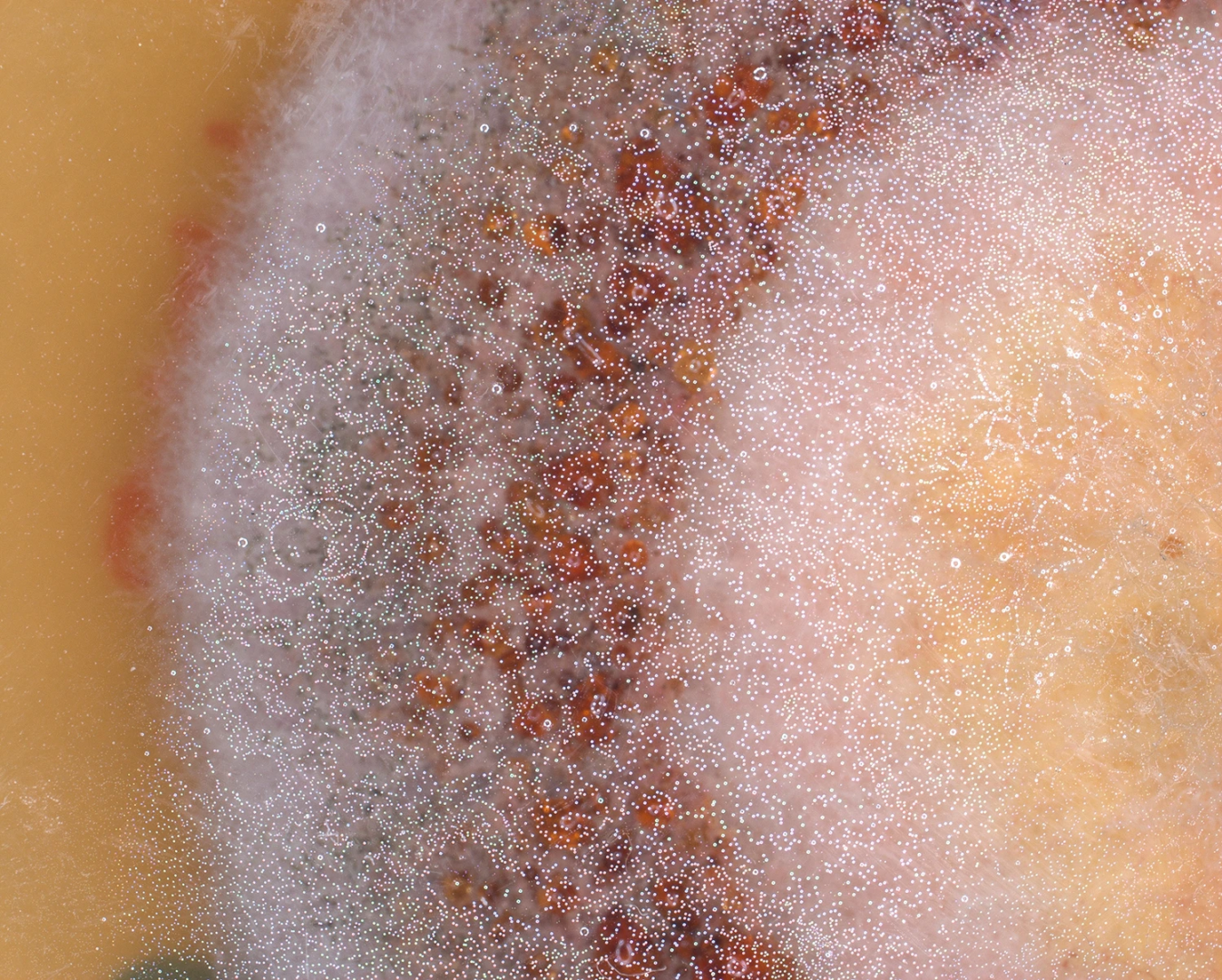

Slime mold intelligence: how brainless fungi simulate cognition and networks

Beyond taste, mold suggests intelligence. Audrey Dussutour, a biologist at France’s CNRS, has shown that the slime mold Physarum polycephalum – known as The Blob – displays a rudimentary form of cognition. Though brainless, it adapts, remembers, and solves problems. In one experiment, researchers placed oat flakes on a map of Japan, positioned over major cities. The mold connected the food in patterns mirroring Tokyo’s rail network, as if solving an optimization puzzle.

Mold in visual art: from Dutch still life to contemporary bio‑art experimentation

Mold appears in the Flemish and French still life of Balthasar van der Ast and Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, where decay gently encroaches on fruit. In Still Life (2001), British director Sam Taylor-Johnson filmed a bowl of peaches, pears, and grapes slowly rotting – an ode to the beauty of decomposition. In 2018, artist Kathleen Ryan created Fool’s Mold, sculptural fruit encrusted with gemstones – agate, malachite, fluorite, obsidian – evoking the colorful, crusty splendor of mold in crystalline form.

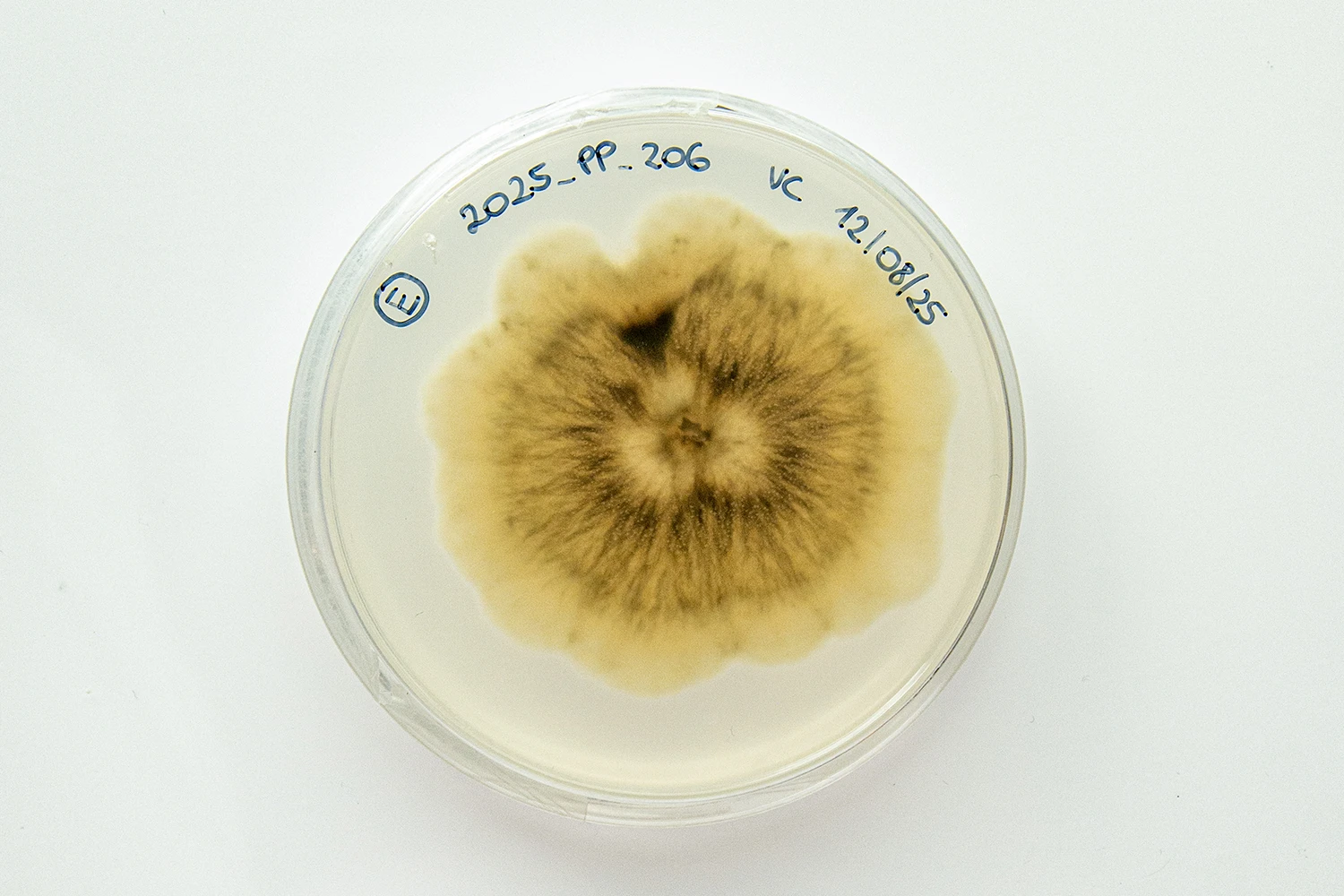

In Italy, the art duo TTOZOI paints with organic materials – flour, water, pigment – and lets time, moisture, and mold do the rest. Their work continues the legacy of Alberto Burri, who in the 1950s created his Muffa (Mold) series. Using pumice, oil, and synthetic glue on canvas, Burri transformed decay into poetic matter. His surfaces resemble spores and growths, textured like infected walls. In the words of Giulio Carlo Argan: «no longer a fiction of a thing, but a pure phenomenon […] not an objectification, but a fusion with reality». Burri’s paintings celebrate transformation. Mold, as both subject and medium, becomes a symbol of regeneration. A meditation on impermanence and the constant flux of life.

Plastic‑eating bacteria: Ideonella and mold’s microbial revolution

In 2016, inside a plastic recycling facility in Japan, researchers identified an organism that quietly upended our understanding of the boundary between the artificial and the natural. It was a bacterium, later named Ideonella sakaiensis, capable of degrading polyethylene terephthalate (PET) – one of the most ubiquitous plastics in the world. Far from being a rogue exception, this microscopic life form revealed a remarkable metabolic strategy: it feeds on plastic. Through the secretion of two specialized enzymes, it breaks down long polymer chains into basic organic molecules, which it then absorbs and metabolizes for energy.

This phenomenon is not isolated. In recent years, scientists have discovered dozens of microorganisms with similar capabilities. Some thrive in industrial soils, others in marine sediments, waste dumps, even within the gut of certain larvae. The microbial world – long known for decomposing organic matter – is now adapting to synthetic materials. Nature, it seems, is quietly folding plastic into its cycles of decay and renewal.

What is the Ideonella sakaiensis?

Since its discovery, Ideonella sakaiensis has become the subject of biochemical research. In laboratories, its enzymes have been engineered to improve efficiency and broaden their scope. Some variants can now act on more crystalline, resilient plastics – such as those used in bottles – within a fraction of the original time. Other scientists have transferred the bacterium’s genetic blueprint into fast-growing marine microbes, allowing the enzymes to function even in saline conditions. Experimental microbial consortia are being developed that combine bacteria and fungi to attack complex plastic composites in concert. The possibilities stretch beyond biodegradation toward full biological assimilation.

In this, Ideonella becomes a symbolic cousin to mold. Like Penicillium notatum transforming a contaminated petri dish into the dawn of antibiotics, or Botrytis cinerea turning shriveled grapes into liquid gold, Ideonella sakaiensis transforms what was considered indigestible and permanent into nourishment. It does not destroy plastic; it metabolizes it. It makes it part of a new ecology.

Mold networks and microbial intelligence in future ecological balance

These plastic-degrading microbes offer more than a potential solution to pollution. They present a deeper vision of ecology itself – one that is not rooted in erasure or removal, but in incorporation. Decomposition becomes a form of creativity. The bacterium is not a destroyer; it is a composer of new chemical orders. As such, it continues the work of mold: slow, invisible, and endlessly adaptive. An alchemist of the margins.

Far from being a threat, decay becomes a process of translation. And like the mold that encrusts fruit in the still lifes of Chardin, or the slime molds that map the logic of cities, Ideonella sakaiensis reveals that nature’s intelligence works through dissolution as much as through construction. Even plastic – our most unnatural artifact – is no longer immune to the appetite of life.

Hebbel’s remark, that we may one day need a magnifying glass to see what a forest was, becomes ever more poignant. Mold, when viewed closely, reveals an ecological intelligence that modern life ignores at its peril. The mycelium, an underground fungal network, facilitates communication and sustains forests by connecting roots and sharing resources. Mold is not a menace to be eradicated but a vector of information and equilibrium. A microscopic custodian of life.

Learning from mold: embracing decay, entropy, and transformation in nature

To gaze at mold is to peer into the logic of entropy, but also into the resilience of nature. It is a world not of decline, but of reintegration. A velvet rot that teaches us to accept change and embrace transformation – not only in nature, but in ourselves.