MOSE project – Methods, Models and Uncertainty: Venice floods as a paradigm for coastal flooding

Four Specialists, one problem to address: Research on a city persecuted by record high tides and a settling landmass done and the salt marshes affected as a result by University of Padova specialists

Venice long-term sea-level rise

Venice’s initial settlers were refugees escaping Germanic tribes and savage Huns to the marshlands where the city currently stands where today has become a tourist attraction thanks to its water canals. The long-term sea-level rise is recorded in the low-lying historical city of Venice, located in the northern end of the Adriatic Sea, a semi-enclosed regional basin with one of the largest tidal and extreme sea levels in the Mediterranean Sea.

For over a thousand years the ancient Italian city has been trying to keep flood waters at bay experiencing high tide surges. Besides being famous for its art, architecture and food the city has also developed a rather infamous reputation for flooding with its severity going up a few notches over the past several years. Which is why the University of Padova has dedicated time and effort into researching its determinants and the gravity of the situation; one of the university’s research team: Marco Marani, Luca Carniello, Andrea D’Alpaos and Davide Tognin walk us through their revelations and ideologies.

The Venice Lagoon – the largest lagoon in Italy

Bounded by the Sile River to the north and the Brenta River to the south, the Venice lagoon is the largest lagoon in Italy and the most relevant survivor of the system of lagoons which in Roman times characterized the upper Adriatic coast from Ravenna to Trieste. Marani commences, «researching both the theoretical and practical points of view regarding the Venice lagoon as well as lagoons as a whole all around the world, this is not a problem that you solve overnight but rather these are the fruits of a long trajectory».

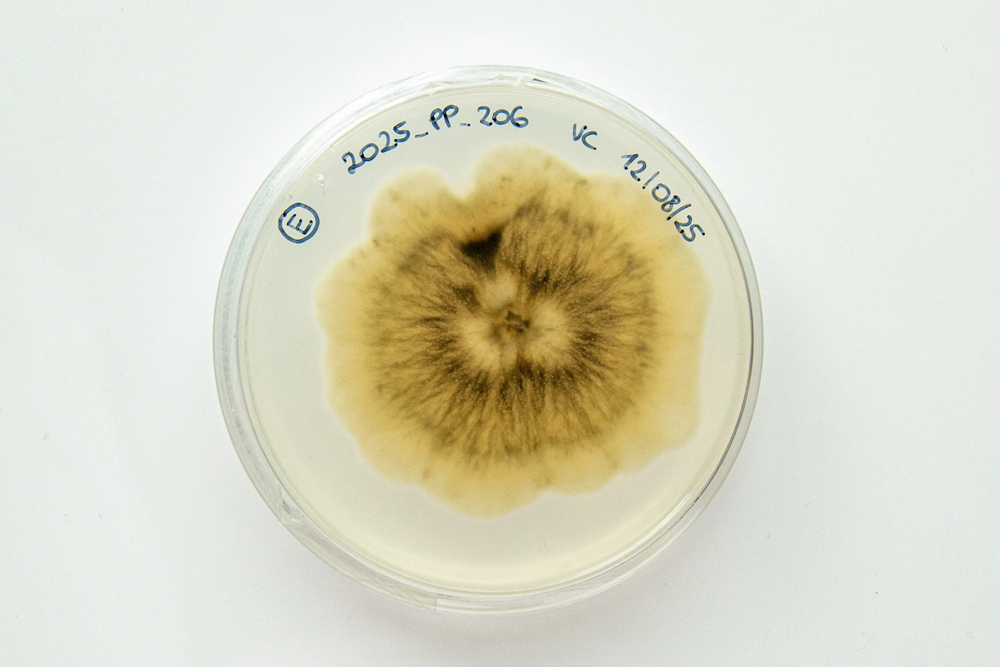

Coastal floodings are considered one of the most catastrophic phenomena of major liabilities to the safety and sustainability of communities worldwide. The event has increased world-wide in the past few decades due to the heightened average sea level rise: an effect brought by the accumulation of tidal and non-tidal processes acting at different temporal and spatial scales. To which Carniello adds, «our idea was to understand the morphological, ecomorphological and bio-morphological solution and the evolution of the Venice lagoon. The topic was aimed to understand how morphological entities of the lagoon and how salt marshes are involved in addition to if and how they are able to keep pace with sea level rise».

Venice is home to a world-renowned wildlife environment, as Italy’s largest wetland and one of the Mediterranean’s most valuable though complicated ecosystems. The ebb and flow of the tides, as well as the brackish mix of fresh and saltwater, maintain a diverse ecosystem. However, since the end of the nineteenth century, the city’s salt marshes and mudflats have decreased by about thirty percent, giving place to industry and coastal development. As the lagoon continues to be dredged to accommodate huge passenger ships, those that survive have been deprived of sediment, poisoned by pollutants, and damaged by waves. Several plans are in the works to limit future development, rejuvenate existing marshes, and establish new ones using silts dredged from the lagoon.

Beau ideal city of coastal flooding

Under the circumstances of the unexpected series of floods that took place in November 2019 – being the city’s second-worst flood recorded in its history – disclose the need to process establishing coastal flooding. The UNESCO world heritage listed city has been titled as the ‘canary in a coal mine’ on account of its coastal flooding worldwide in addition to the fifteen flood events the city experienced in a month posing as a paradigm study site for coastal flooding. D’Alpaos explains, «in the past it was higher and due to human activities mainly ground water extraction but now this subsidence rate has decreased to one millimeter a year, while it is a combination of the two is also a natural process. The lagoon is subjected to natural subsidence but one thing to highlight and clarify is that this issue contributes to the rate or relative sea level rise which is constituting to around four or four point five millimeters per year but IPCC predictions for the northern Adriatic suggest much faster rates in the future».

Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico – MOSE

The MOSE, named for the acronym of its Italian name ‘Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico’ gate system, a fitting name derived from Moses and his mastery over the sea, was planned back in the Eighties before climate change was a well-known concept. The system is designed to control waters flowing into the three inlets connecting the sea to the Venice lagoon based on a system of hydraulic floodgates. These measures were designed last century in the Seventies and were expected to be operational in 2018 but its completion has been postponed at least to the end of 2021.

«When the system is in use during the Acqua Alta events this will have some effects on the morphological evolution of the lagoon and it is key to know because the Venice lagoon is evolving and becoming deeper by observing the information and studies we have on it from the past. The salt marshes are also disappearing and the MOSE system is contributing to this process, some say that Venice is the lagoon and there is no Venice without it and with doing so we are thinking about a different city, knowing this we have to start thinking how counteract or mitigate this effect».

[envira-gallery id=”116631″]

‘Aqua Alta’

Because of Venice’s uncommon topography, built among canals has as a result made it susceptible climate change and is frequently exposed to floods, locally known as ‘Aqua Alta’ meaning ‘High Waters’: a recurring phenomenon most of all during the winter time where tides are around eighty centimeters or more above the mean sea level. Over the years, Venice has been battling rising water levels. Due to various factors, such as man-made and natural, it floods about a hundred times a year.

D’Alpaos discloses information that people rarely know, «People who should manage the system do not know this or they do not say it but 110 centimeters Punta della Salute is the threshold. So, when the forecast tides are higher than 110 they decide to rise the gates, but what people do not know is that according to the observations of tidal levels within the lagoon during these first closures is that the water level within the lagoon stays well below the 110 to around sixty – seventy centimeters and this makes quite a difference for the salt marshes whose elevation is about between fifty-five centimeters and sixty-five centimeters above Punta della Salute. If the threshold is 110 and you raise the gates and keep the water level at severity this makes all the difference; optimally managing the rise of the gate is a key point that the University of Padova department of civil engineering has been studying for a while».

The dark side of the MOSE

«One of the questions that we have been asking ourselves was whether the accretion the marshes need to keep pace with sea-level rise otherwise they drown whereas – this accretion was the consequence of the everyday tide – or if it was the result of a few episodic events. We started analyzing with field experiments accretion and sedimentation rates in relation to the everyday tide or to the Acqua Alta events and it came out that these events along with Aqua Alta events are those which critically affect and control salt marsh dynamics in the vertical frame and so they are essential to marsh survival in the face of in particular sea-level rise with the face of poor availability in sediment dynamics».

The entire MOSE project has been marked by episodes of corruption, sanctioned in a trial which has just ended and which revealed a frenzied activity of bribery to cover up work and plans that were bad in design and even worse in execution. We now learn there is a thing as too much gate closure. One would think that if the hydraulic system gate were to be closed more often that would benefit the city’s infrastructure and ecosystem, but rather the complete opposite is true to nature.

Marani explains, «Closing the MOSE too often gives rise to other consequences, we cannot simply close it whenever we feel like it because this gives cause to more problems for the environment. These problems or damages are now quantified; more so like an alarm saying look now you’re devising your procedures but these procedures should be kept into account that gates should be closed only when it is deemed necessary not more and not less. If closed too often the marshes will not accrue and will fall behind with respect to sea-level. Losing around one millimeter per year on average; an additional loss with respect to the rising sea-level, worsening the situation of the marshes».

Venice – Sinkage of a historical city

Over the past millennium, the piles have been sinking into the lagoon bed at a rate of around two to four centimeters per century. Due to the extraction of water through artesian wells, the land subsidence rate has increased. The rise of the sea levels during the 20th Century was also caused by the increasing temperature of the Mediterranean. Marani assures, «the city has been sinking overtime but now this ‘sinking’ has slowed down. The residual sinking, if you may, is just a natural process. Something that takes place in every coastal area in the world; sedimentary zones are subject to that and it is something that human beings are not responsible for and so that is just a physiological being of the sinkage».

With the frequency of flood catastrophes increasing in a gradual way over time and is predicted to continue increasing due to the ever-rising levels in sea and subsidence. While it is a little more than fascination for visitors and tourists it is an inconvenience for Venetians; ground floor doors must be sealed with barriers, waterproof boots must be worn and if water levels are high, boats are unable to pass the Italian city’s bridges until the water descends again. Carniello divulges, «If we want to protect Venice from other cities within the lagoon and from most extreme Aqua Alta events, the solution is to separate the lagoon from the sea. Conditions and circumstances have decided that the best current solution is the MOSE and what we noticed with our research and campaigns is that while yes MOSE will be able to withstand the issue for thirty or fifty years, we will have to come up with something else after that».

The short blanket syndrome

World-wide relevance as the site is considered a UNESCO world heritage place and has always relied on a foreign trade driven economy and with the MOSE gate system the city has been making efforts into maintaining accessibility between sea and land to safeguard its interests. David Tognin’s work in the research quantifies the closing of the lagoon with respect to its morphological dynamics, «what will the Venice lagoon be like in the next century? What will be the morphology of the system and in order to understand how to deal with a new system that would regulate the dynamic of the water and sediment transport and the connection from the lagoon to the sea we must understand how to modify and manage this new type of environment».

According to Tognin, the contribution of the everyday tide and the storm surges is not equal to the sedimentation of the marshes; a striking contrast to what has been told in previous years when the sedimentation of the marshes were seen as rather a continuous process. «The natural and urban environments are somehow competing – what we need to do is try to find a compromise which we can do by trying to understand what will happen in the future in order to help the stakeholders and decision makers understand what we can do if we want to save both the city and the nature or at least have them survive together in a different system than the one we have created in the past one thousand years».

Illustrating it to a short blanket, the original paper’s title was called ‘The Short Blanket’ whereby protecting the city is more like pulling the blanket upwards towards your neck but in doing so your feet are left exposed. Finding a compromise is key, «you cannot just preserve the environment just as it has been over the past hundreds of years. Things will have to be different, we have to make a decision; one that has consequences, quantitative information lets you know the reality of how it is».

Possible outcomes to a world class crisis

If left untreated the elevated water level will cause the ancient buildings to deteriorate and collapse. It will also allow the iron tie rods to corrode and break. According to a local association, during the time of the flood (November 2019) hotels reported a drop of thirty-five percent putting a dent into the three-billion-euro industry and it was reported that more than eighty percent of the city was underwater at the peak of that flood event. Not only does the hospitality industry struggle to stay afloat but others like tourist and food industries are also affected not only by the floods that occur but with the closing of the MOSE system, Marani explains that this interferes with the movement of the ships coming in and out of the city, «this affects investors interested in the harbor, stakeholders and employees will start to worry. It is not possible to preserve the city as it is because whatever solution you find we will have to sacrifice. People have different views on what should be prioritized even though the city is a priority for everybody. We already know that in thirty years the MOSE will have to close so often that it is likely going to impact the harbor and these measures should be considered now because it takes thirty years to come up with a collective decision for the future».

The Venetian lagoon is over 500km2 in total, but has an average depth of just one meter. High tides and storms can have a severe impact on this kind of wetland environment, in order to be able to manage such events in the future measures should be taken and options besides the MOSE flood gate system should be considered, «we made some work and scenarios seeing what would happen with the data we have collected if the MOSE was activated at different thresholds or water levels. If we are able to close it later and accept higher water levels within the lagoon we can counteract this process a lot, by adding 10 centimeters of acceptable water level in the lagoon can moderate this negative effect on the marshes».

The Baby MOSE project

Carniello explains further: «There is another structure called ‘The Baby MOSE’ preventing the flooding of Chioggia at a higher level. Therefore, if we can do something at a local level, we can gain these few centimeters in difference from being able to close later and less frequently and we can counteract and reduce the negative effect we have on the marshes». As part of the MOSE intervention program The Baby MOSE was the project proposed for the built-up area of Chioggia and saving it from flooding along the Vena Canal and the urban and environmental upgrading of the area.

Needing to rely on hard evidence has become a necessity above all else because part of the natural process of being human is to look at our immediate needs and interests and can open up the public’s eyes. D’Alpaos concludes, «we want to make clear that defending Venice from flooding is not under discussion, so our paper does not question the need to protect the city of Venice. However because the MOSE will likely protect Venice and the other cities around the lagoon, the MOSE might have negative effects on the morphology and our role is to highlight these possible negative effects and possible countermeasures to prevent a faster sinking of the marshes or a faster morphological degradation and erosion of the lagoon».

Marco Marani, Luca Carniello, Andrea D’Alpaos, Davide Tognin

All from the University of Padova with ranging areas of expertise from different departments like Department of Civil, Environmental and Architectural Engineering, Center for Lagoon Hydrodynamics and Morphodynamics and the Department of Geosciences all coming together to study the nature of the Venice Lagoon, its coastal flooding and the everchanging salt-marsh sedimentation dynamics due to this crisis.