Mycelium is emerging as a viable material for packaging and textile design

A fungal infrastructure hidden underfoot is turning agricultural residues into composites, surfaces and textiles. Mycelium expands the role of biology in circular resource use

Mycelium — a quiet infrastructure under the surface

Mycelium is the vegetative apparatus of fungi: a network formed by hyphae, microscopic filaments capable of multiplying rapidly through soils, substrates and decomposing matter. It grows in layers, fusing into a tissue that holds humidity, transports nutrients and communicates chemically. It remains largely unseen, while mushrooms appear only as reproductive structures. The visible part is a temporary event; the mycelium is the stable structure. Fungi rely on this network to digest the world: cellulose, lignin, complex organic waste.

The ability to convert discarded matter into new growth positions mycelium within broader ecological cycles, both in forests and controlled environments. It is not a static material but a process, constantly modifying itself as conditions change. Understanding this dynamic behavior is essential for those who want to use mycelium beyond the forest floor.

Living raw materials: engineering growth as fabrication

The shift from biology to material science happens inside laboratories and facilities where controlled growth replaces spontaneous colonization. Agricultural by-products such as hemp hurds, straw, sawdust or other cellulosic residues are used as feedstock. Once inoculated, the mycelium spreads through the substrate, acting as a natural binder. The outcome can be firm like a composite or flexible like a non-woven sheet. Growth cycles, humidity, oxygen exposure and temperature modulation become the equivalents of molding or polymerization.

The material is shaped while it is still alive. When the desired architecture is reached, heat or dehydration inactivates fungal metabolism, fixing the form. As a production system, mycelium reduces steps: there is no chemical polymer synthesis, no spinning, no weaving. The organism performs several tasks autonomously, guided only by the matrix and environment. The consequence is a new generation of raw materials that emerge biologically rather than being extracted or synthetically engineered.

Rethinking materials through sustainability metrics

The interest surrounding mycelium intensifies where environmental assessments are a priority. Fossil-fuel polymers involve high energy and long-term waste. Animal-derived leathers require livestock and intensive resource use. Conventional textiles depend on agricultural land, water and dyeing cycles. Mycelium-based materials grow from low-value biomass and do not require light or fertile soil. Production can take place in compact indoor facilities close to waste streams. End-of-life scenarios rely on biodegradation: if untreated with synthetic coatings, the material can return to soil in weeks or months.

The concept of sustainability becomes operational rather than aspirational. Mycelium converts local residues and avoids persistent waste. The main environmental burden remains in growth control: maintaining sterility, humidity and temperature still requires energy and resources. But the comparison with petroleum-based plastics or conventional textiles reveals a different balance between input and impact.

A new material culture: objects emerging instead of being manufactured

Mycelium challenges traditional industrial imagery. Instead of assembling parts, the object forms as a continuous whole. Garments can be grown to shape. Packaging is formed directly in the mold that defines its final geometry. Surface textures, density and mechanical response derive from biology rather than milling or injection. Each product is the result of a growth event.

The boundaries between agriculture and manufacturing become blurred. Instead of extracting resources to feed production, production becomes a phase of cultivation. Human intervention reduces to guiding the behavior of an organism. A material culture rooted in innovation is not about novelty for its own sake, but about shifting manufacturing logic from extraction to growth.

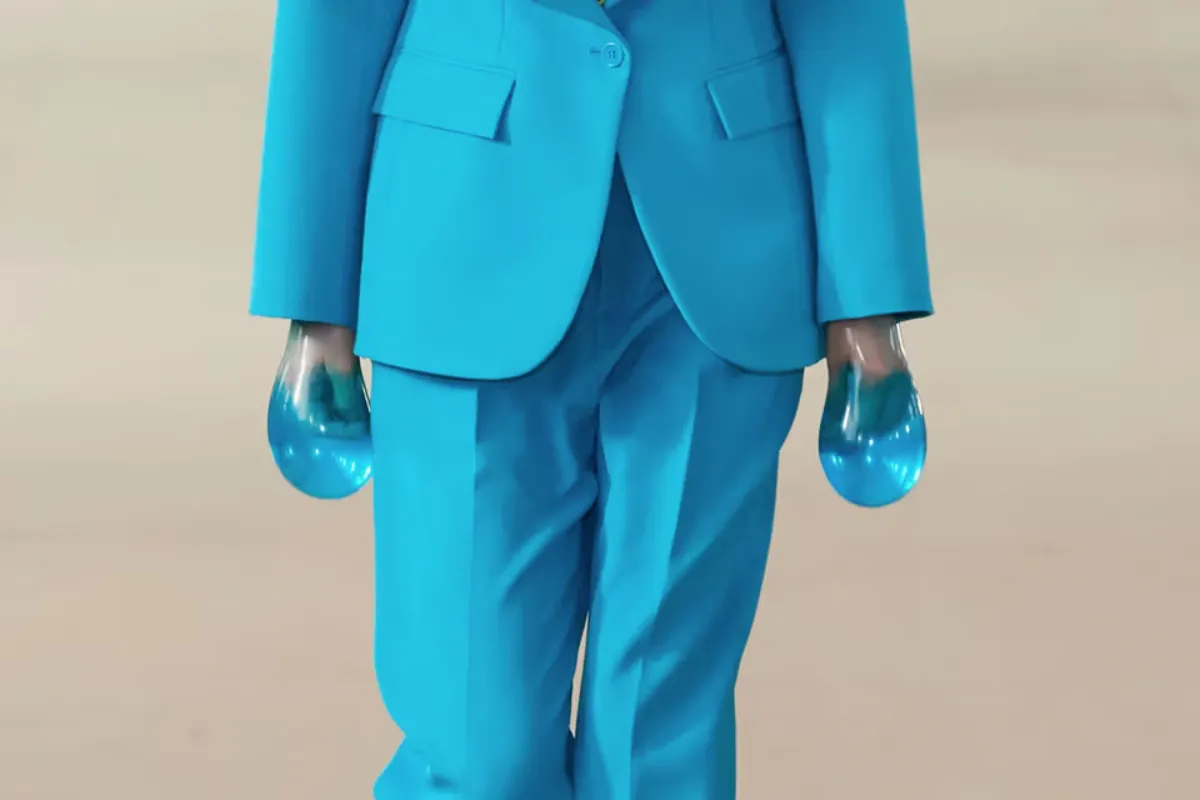

Textile ambitions: a fabric without fiber

The idea of mycelium as textile derives from its non-woven nature: a continuous planar sheet where intertwined hyphae replace threads. Designer-led laboratories work to achieve flexibility, softness and mechanical resistance aligned with fashion standards. Natural colors remain limited to earthy or off-white tones unless surface finishing is applied. Breathability and comfort depend on the porous microstructure. The absence of spinning and weaving also means absence of seams: modules grown to shape can reduce cutting waste.

The challenge is durability. A mycelium sheet must withstand friction, humidity and repeated wear without losing cohesion. Research focuses on densifying the network during growth, adapting species and controlling fiber thickness. The potential exists for a new category of biodegradable textiles, but mechanical performance still sets limits on widespread apparel use.

Circular economies: composites grown to replace polymers

In sectors where flexibility is less critical, mycelium-based composites have already reached commercial scale. When grown around substrate particles, the fungal network creates a rigid matrix that is lightweight and bio-derived. Such composites occupy the same functional space as foam packaging and protective inserts. They absorb impact, insulate thermally and can be tailored to specific shapes without post-processing.

In architecture and interior design, panels show acoustic absorption and low thermal conductivity, suitable for partitions and temporary installations. These solutions align directly with the principles of circular economies: waste biomass becomes a structural product and later returns to nutrient cycles. Scalability remains tied to the availability of agricultural residues and the efficiency of growth facilities. Standardization is a primary concern: biological processes fluctuate, and performance tolerances must tighten before adoption in demanding applications.

Limits that define the future of bio-fabrication

The performance of mycelium is not universal. Water absorption can destabilize structures. Fire behavior requires treatment to meet safety codes. Growth speed varies across fungal species and affects manufacturing throughput. Uniformity across large molds remains technically complex. Contamination risks require controlled environments similar to cleanrooms. Costs depend strongly on logistics: substrates must be local to preserve environmental advantages.

For fashion, tactile standards impose strict expectations: consumers associate quality with specific sensory cues. The shift from niche experimentation to mass availability demands investment, regulatory clarity and predictable scale. Biological variability, once seen as a strength, becomes a limitation when consistency and certification are required.

The cultural meaning of living matter

Mycelium introduces questions that exceed performance metrics. What does it mean to live among materials that once were alive and will return to soil. The presence of fungal systems reflects a cultural shift: valuing processes that regenerate instead of extract.

The inclusion of mycelium in design invites a reconsideration of the relationship between humans and the biological environment. It positions matter as a former metabolism. Innovation extends into cultural transformation: industries integrating principles that reflect ecological intelligence over mechanical control. Adoption requires accepting that imperfection, variability and adaptation are inherent properties of living matter.

Industrial reality and geographical proximity

If growth relies on region-specific residues, production can be decentralized. Shorter supply chains reduce emissions and increase territorial autonomy. This model differs from petrochemical infrastructures concentrated in few locations. It mirrors agricultural logistics and requires knowledge of substrates and species suited to each context.

Material behavior depends on the interaction between mycelium and local biomass: hemp hurds behave differently from rice husks or hardwood sawdust. Expertise is biological and territorial. Mycelium manufacturing becomes a way to reconnect production with landscapes and resource flows. The network beneath the soil becomes a metaphor for the industrial networks emerging above it.

The crossroads of biology and construction

Designers explore transitional fields such as temporary structures and experimental pavilions. Mycelium panels offer low density and natural thermal regulation, though not yet suitable for load-bearing use. The construction sector demands long service life, moisture resistance and certified performance.

Hybrid assemblies, combining mycelium with timber, natural fibers or bio-resins, are being tested to improve mechanical properties. The aim is not to replace concrete or steel but to complement them in applications where biodegradability and low environmental impact are priorities. Architectural experiments support a broader hypothesis: the built environment may incorporate materials closer to natural cycles, accepting deterioration as part of a planned lifecycle rather than a failure to avoid.

Learning from the organism: a transition still in motion

The most radical potential of mycelium may not be the products but the paradigm it suggests. Its role in ecosystems is decomposition and renewal. Applied industrially, it implies that materials can embody regeneration. Growth takes place from the inside outward; structure emerges without machining. Repair is possible by allowing colonization to resume. Waste is not an end point but a substrate. A material born from decomposition becomes a manifestation of biological intelligence applied to manufacturing.

Mycelium has evolved from scientific curiosity to industrial candidate, yet most impact remains ahead. Transformation timelines depend not only on research: they rely on regulation, cost, culture and the will to reorganize supply chains. Mycelium will not replace every material; its applications are sector-specific and performance-dependent. Yet its presence has shifted expectations.

A biological system once invisible underfoot now enters design studios, factories and conversations about the future of matter. The organism becomes infrastructure. The material becomes process. And the underground network of fungi becomes a reference for how industries might regenerate rather than exhaust the resources they rely on.

Mycelium

Mycelium is the vegetative network of fungi, formed by microscopic filaments called hyphae. It grows through organic matter, breaking down biomass and binding particles together. This natural structure can be cultivated to create materials for packaging, textiles, and construction. When deactivated, mycelium becomes a lightweight, biodegradable composite. Its performance depends on fungal species, substrate, moisture, and controlled growth conditions.

Debora Vitulano