Why re-reading old images is a subversive act?

Rodrigue de Ferluc reassembles Paris Match archives to question the meaning of images and their reuse —from glossy celebrity portraits to war reportage—in an era of algorithmic control

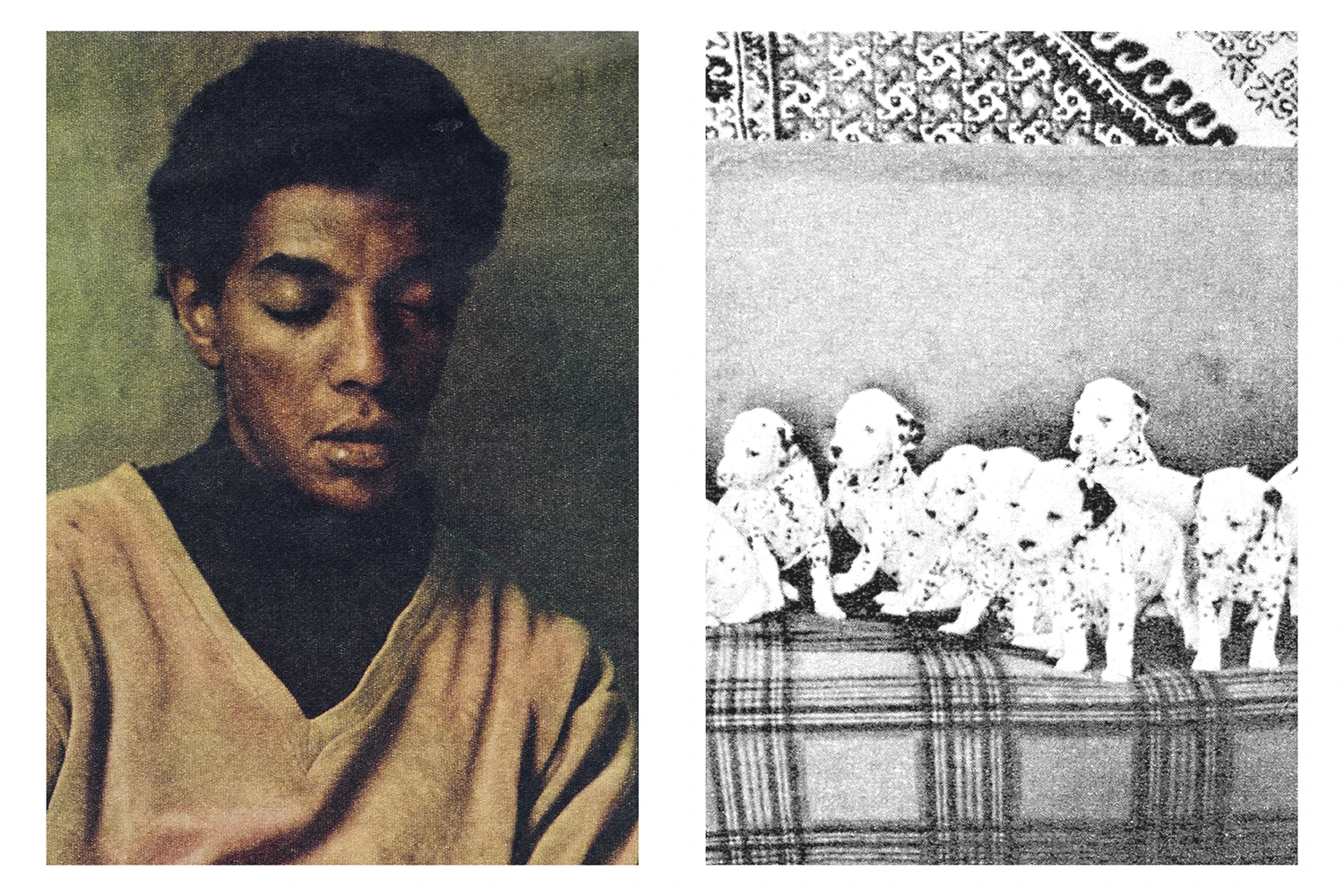

Augure by Rodrigue de Ferluc explores the afterlife of images and the collective memory of photography

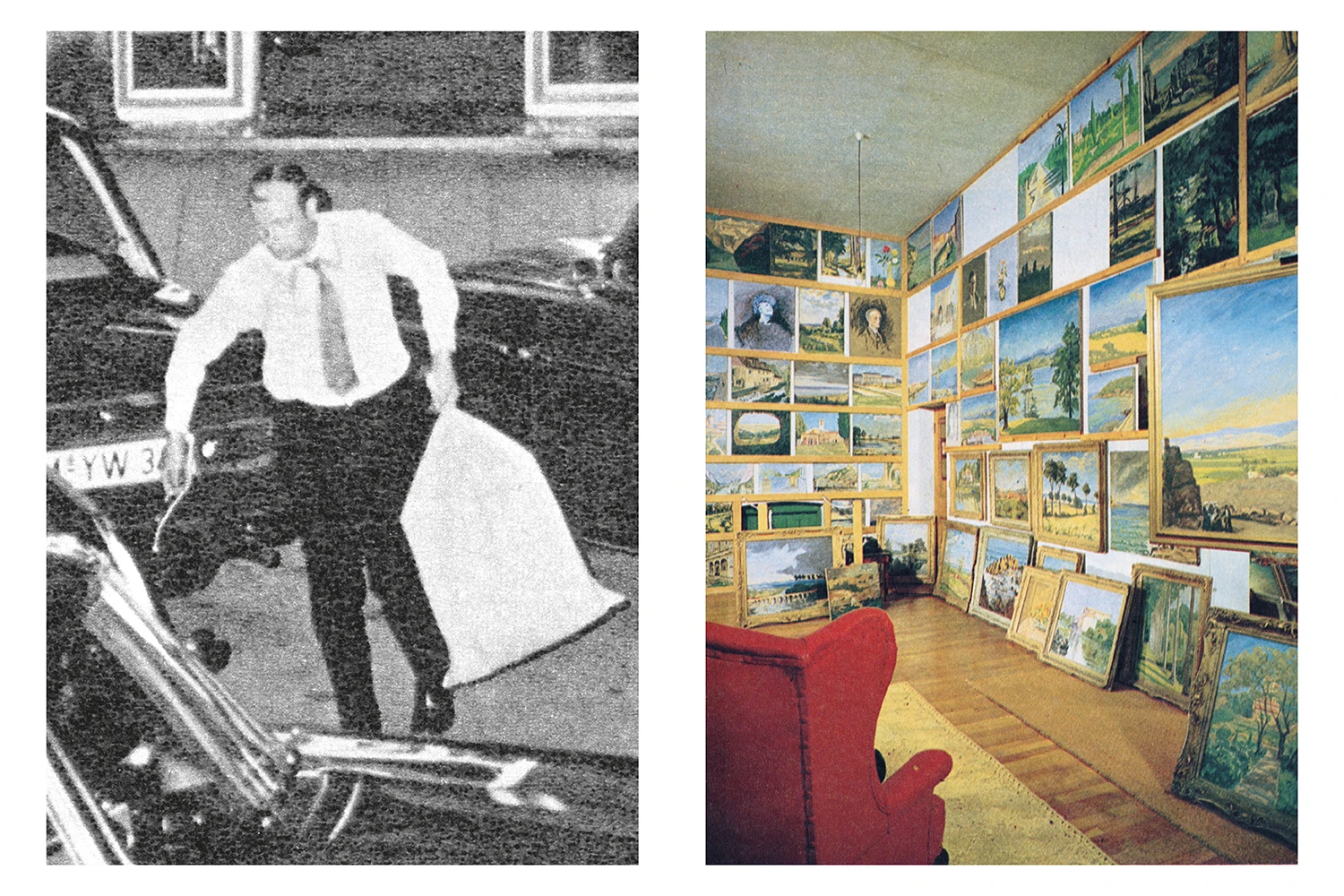

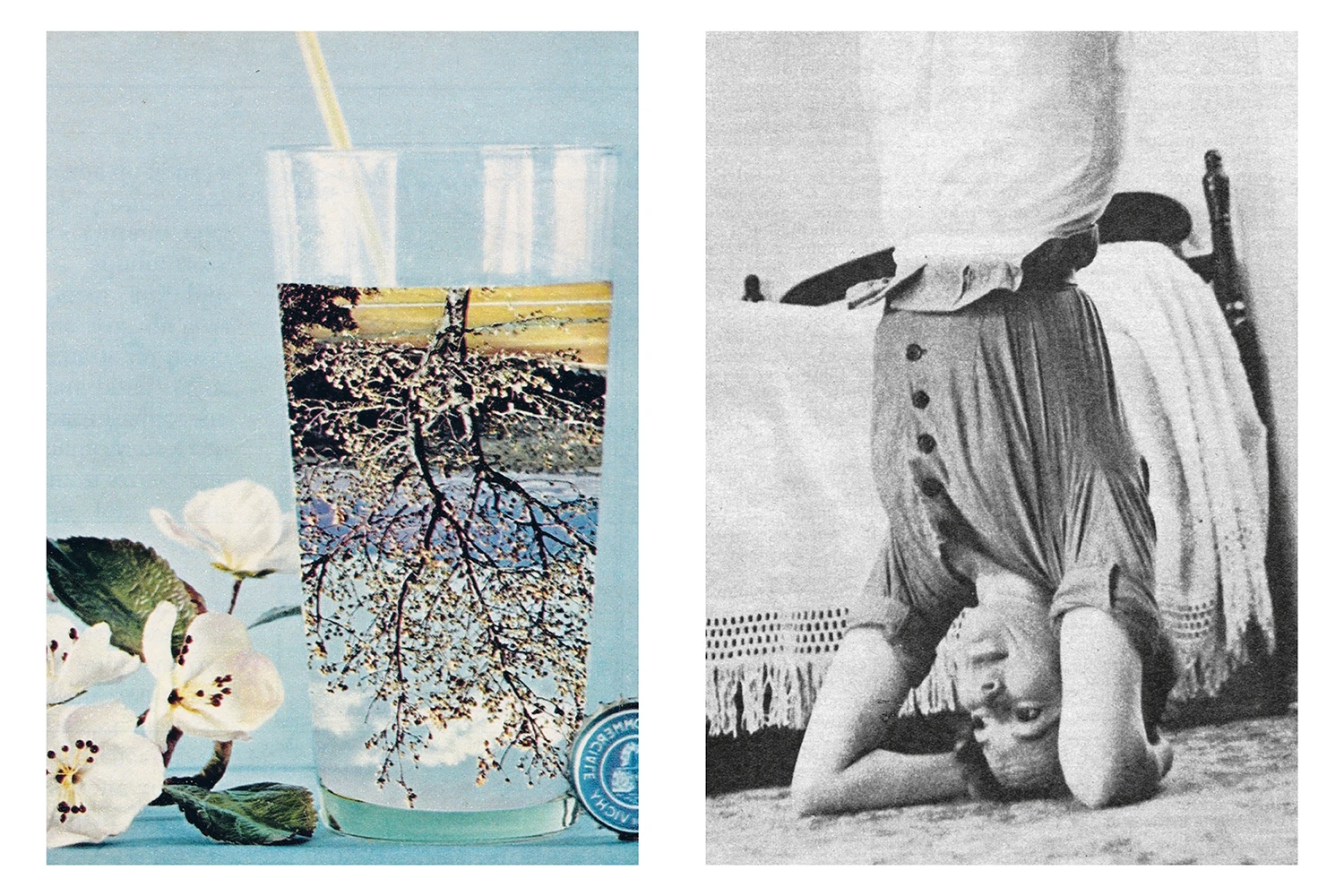

This approach is both economical and political. In an era defined by image overproduction and digital waste, de Ferluc argues for a logic of reuse. His photobook, published in May 2025 by Rnvp, consists of collaged and recomposed images from Paris Match. It is a work of reappropriation and retransmission, consistent with an artistic practice that privileges montage, displacement, and assemblage over the creation of new objects. “Art is less about production than about editing and rewriting,” he explains.

Today, the ambiguity persists, though in a new form. Audiences have become more cynical, more aware that photographs rarely guarantee truth. What matters is less the veracity of the image than its ability to navigate through the networked flows of the present. “We are all reporters and advertisers of our own lives,” de Ferluc observes, citing the Bulgarian poet Athanase Daltchev, “human billboards who carry our own publicity.”

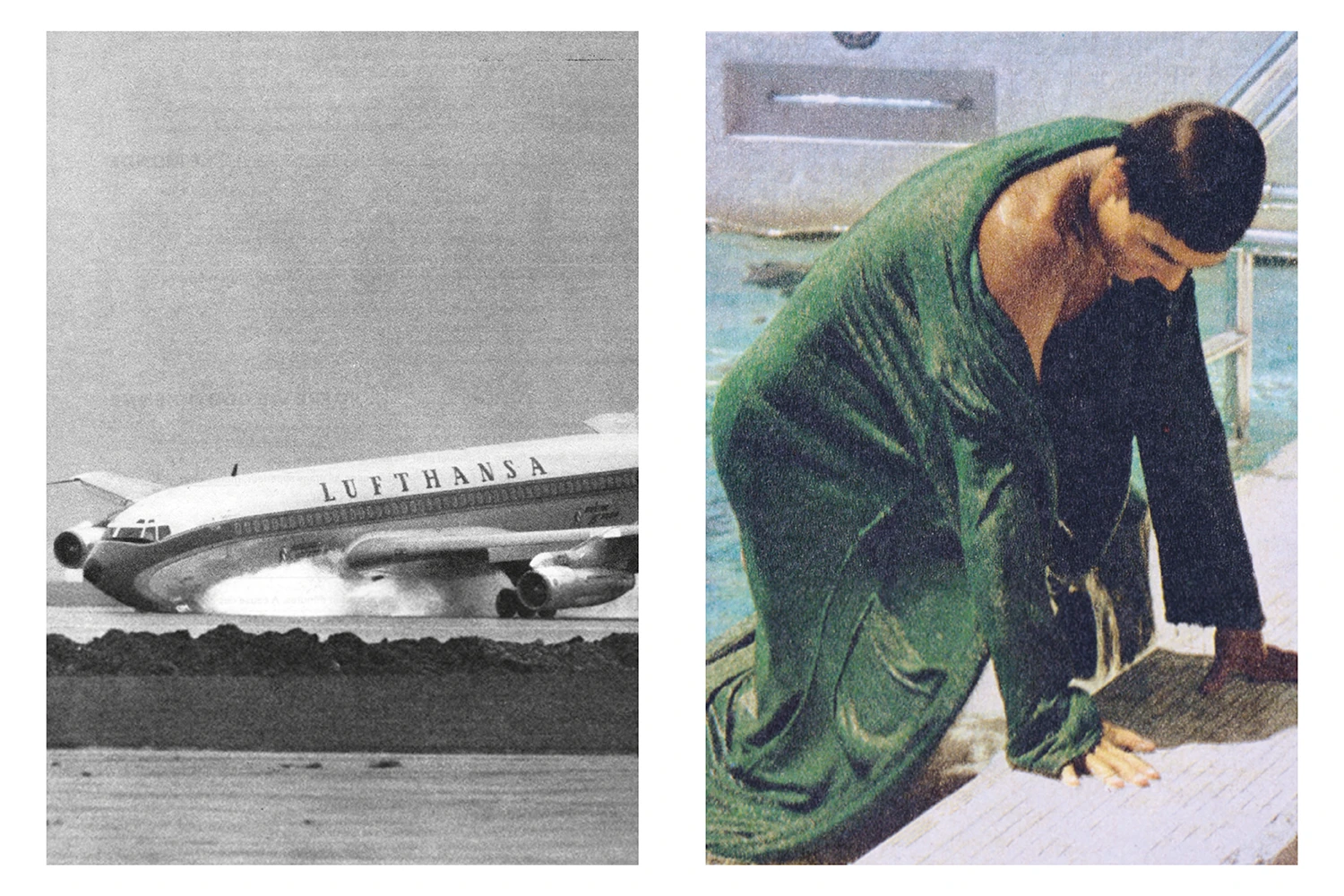

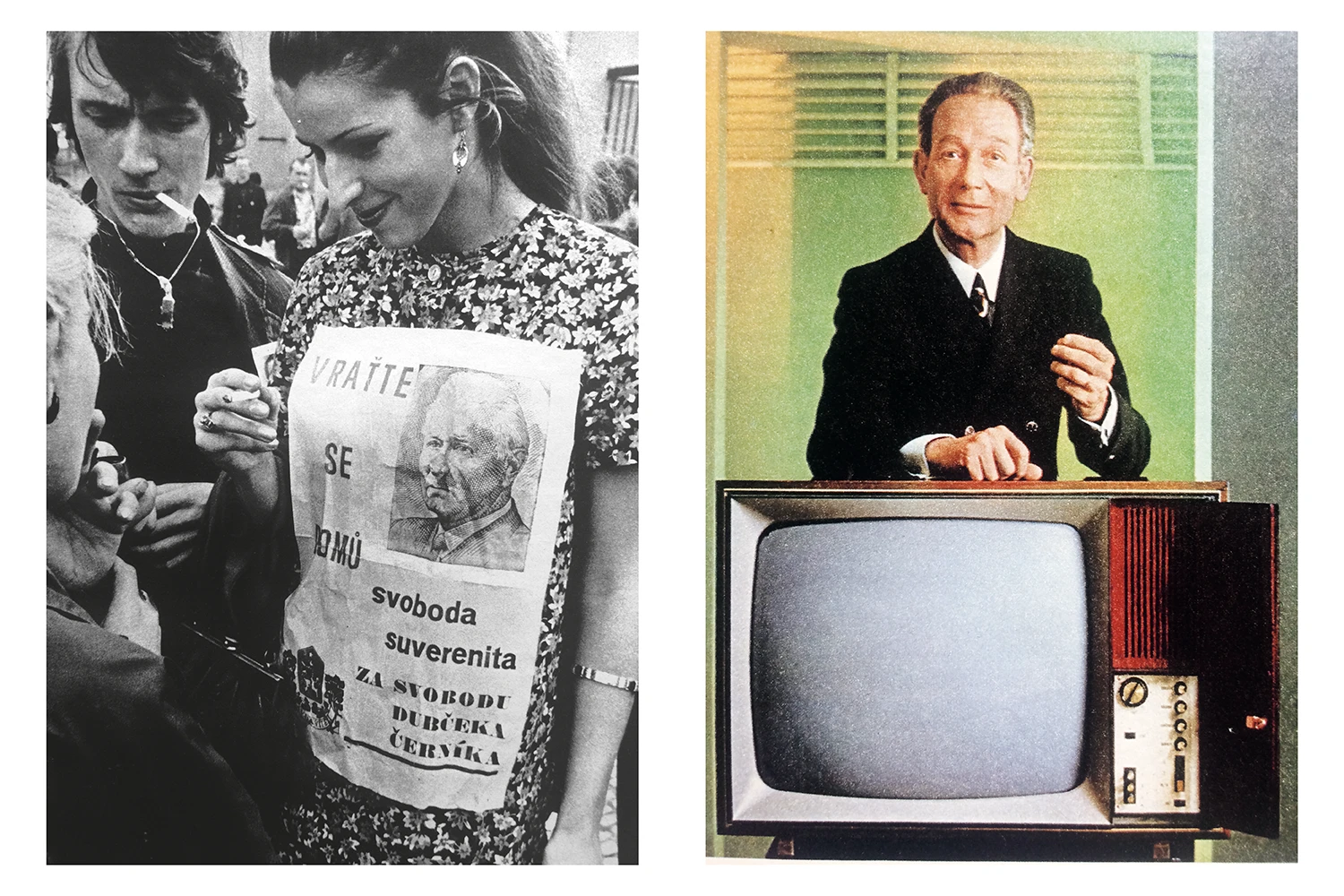

The project Augure by Rodrigue de Ferluc begins almost by accident, in a small second-hand shop, with the discovery of around sixty issues of Paris Match. For thirty euros, the photographer carried home sixteen years of history – from 1958 to 1974 – years in which print media still safeguarded a degree of editorial independence, in stark contrast to television, which remained under state control in France.

“I bought them without knowing what I would do with them,” de Ferluc recalls. “At first, I was simply drawn to the pale blue eyes of Hollywood stars, or I felt pity for the confused gaze of an anonymous soldier.”

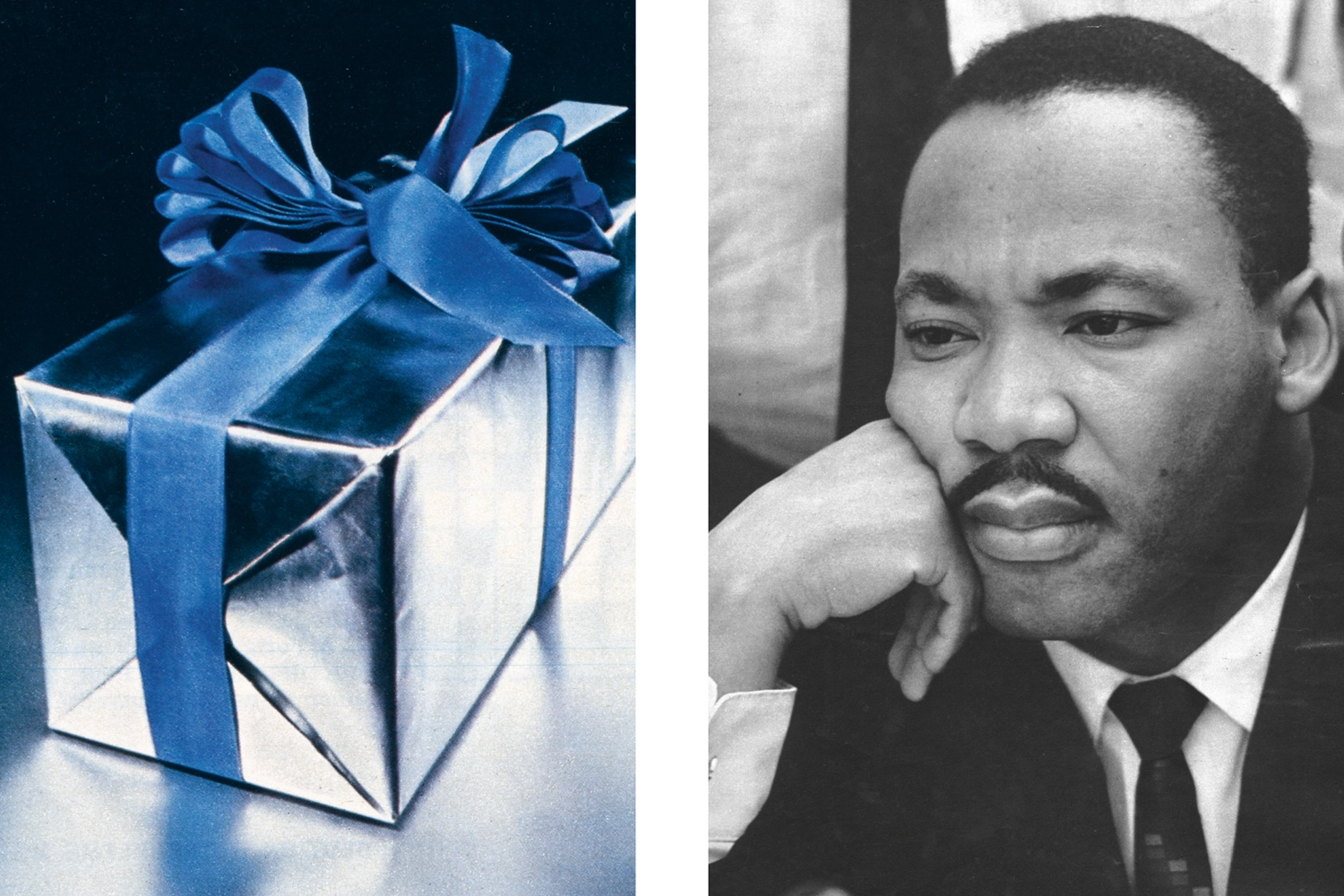

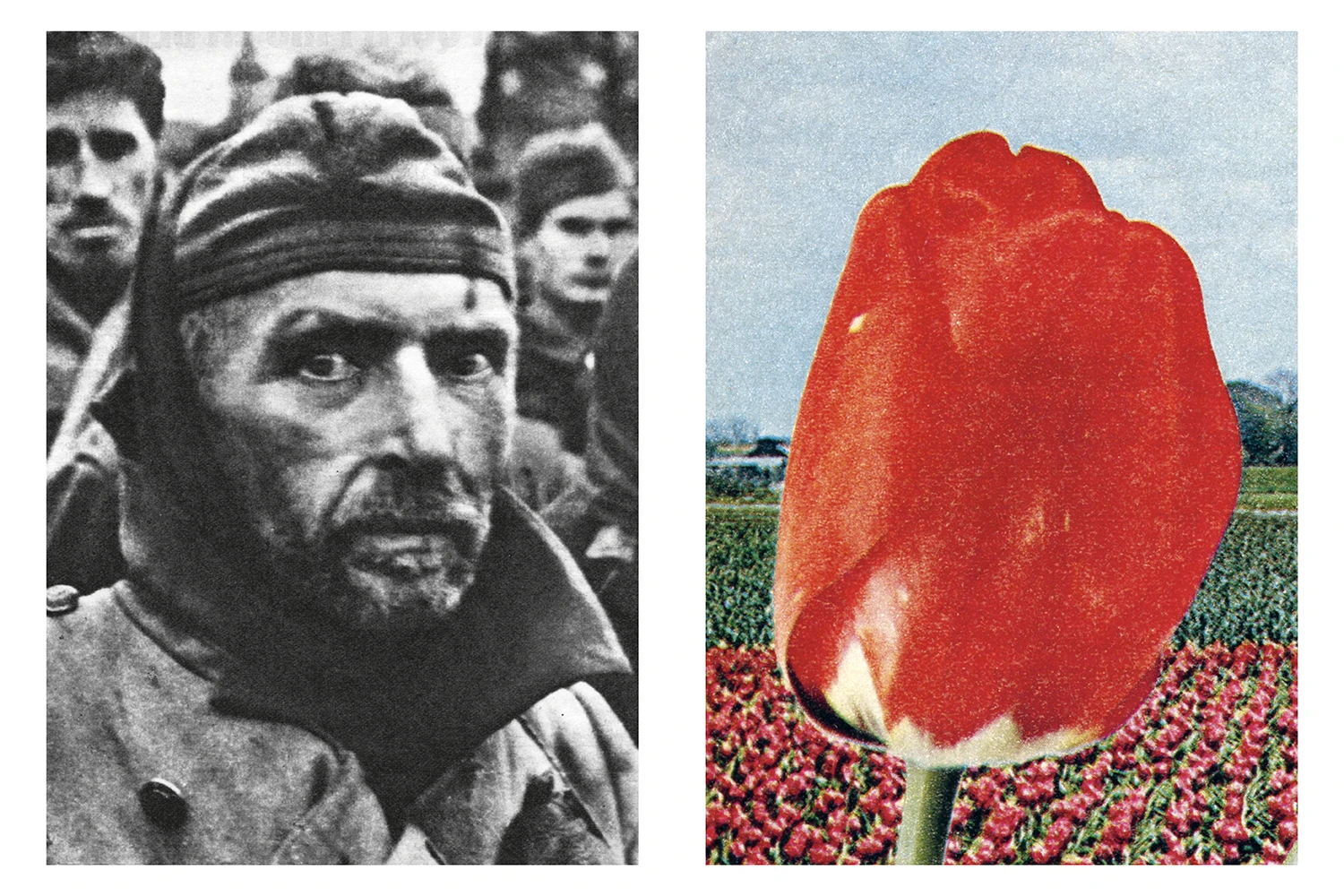

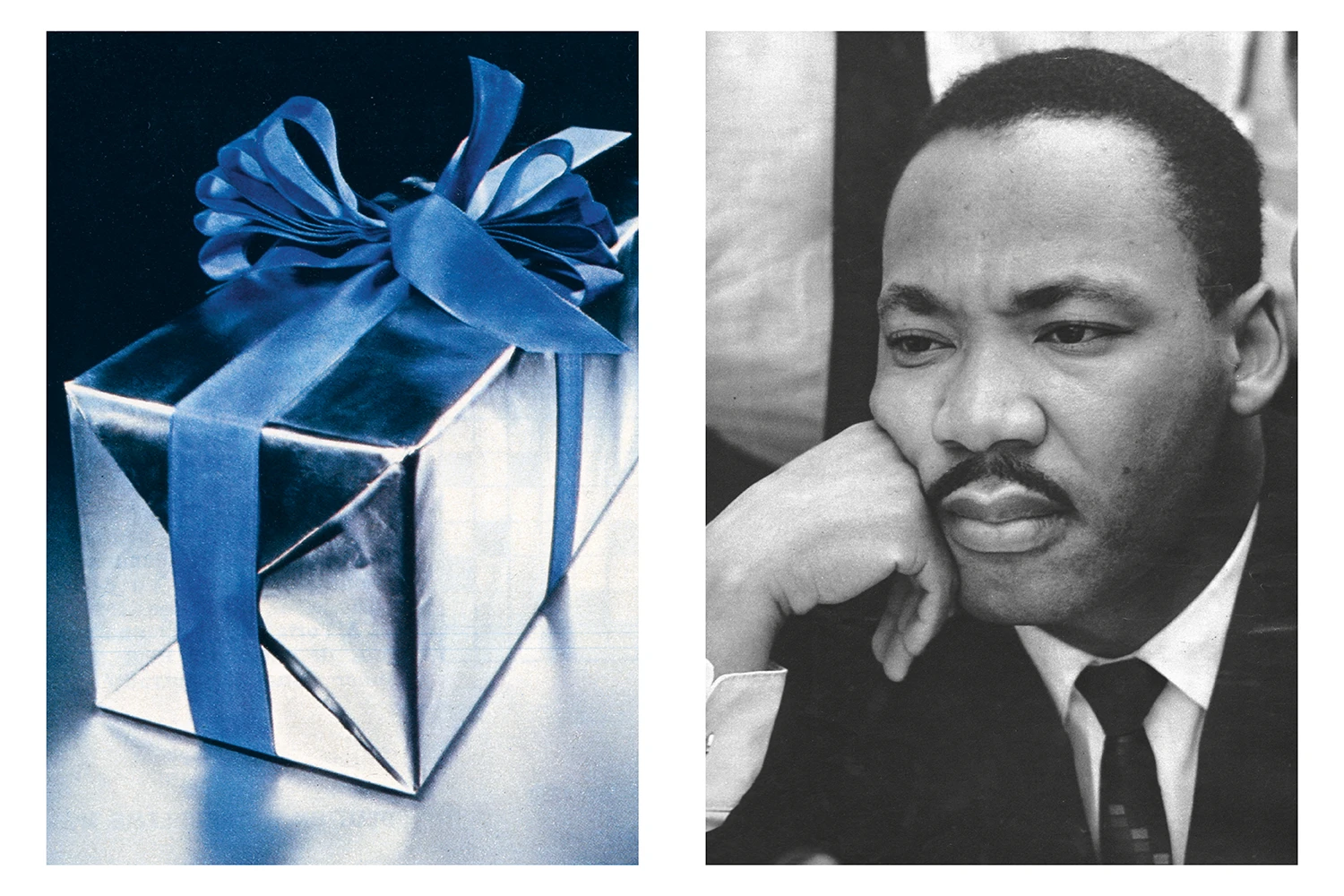

The pages of Augure juxtapose war reportage with glossy consumer advertising, images of political conflict with portraits of celebrities. This tension reflects the fragile equilibrium of the second half of the twentieth century: an era when images were already mediating between spectacle and violence, aspiration and catastrophe.

Paris Match and the birth of modern photojournalism in post-war Europe

To understand Augure, you consider the role of Paris Match. Founded in 1949, the weekly became an influential magazine in post-war Europe. Often described as the French counterpart to Life, Paris Match was more than just a news outlet: it was a cultural institution. Its motto, “Le poids des mots, le choc des photos” (“The weight of words, the shock of photos”), encapsulated its philosophy.

Through vivid, large-format photography, the magazine brought global events into the homes of millions of readers: wars in Algeria and Vietnam, the space race, May ’68, celebrity scandals, fashion, and political power struggles. It blurred boundaries between serious reporting and spectacle, placing images of burning villages next to glamorous portraits of Brigitte Bardot or Catherine Deneuve.

In France, where television remained tightly controlled by the state until the mid-1970s, Paris Match offered a different kind of visual literacy. It presented itself as both eyewitness and entertainer, collapsing distinctions between news and publicity. For a generation of readers, it defined how history looked – glossy, immediate, often sensational.

By retrieving sixty issues of Paris Match, de Ferluc unearthed not just a media archive, but a visual DNA of modern France, preserved in the fragile pages of mass print culture.

Why old photographs never lose meaning: Rodrigue de Ferluc on the semiology of war, fire, and collective memory

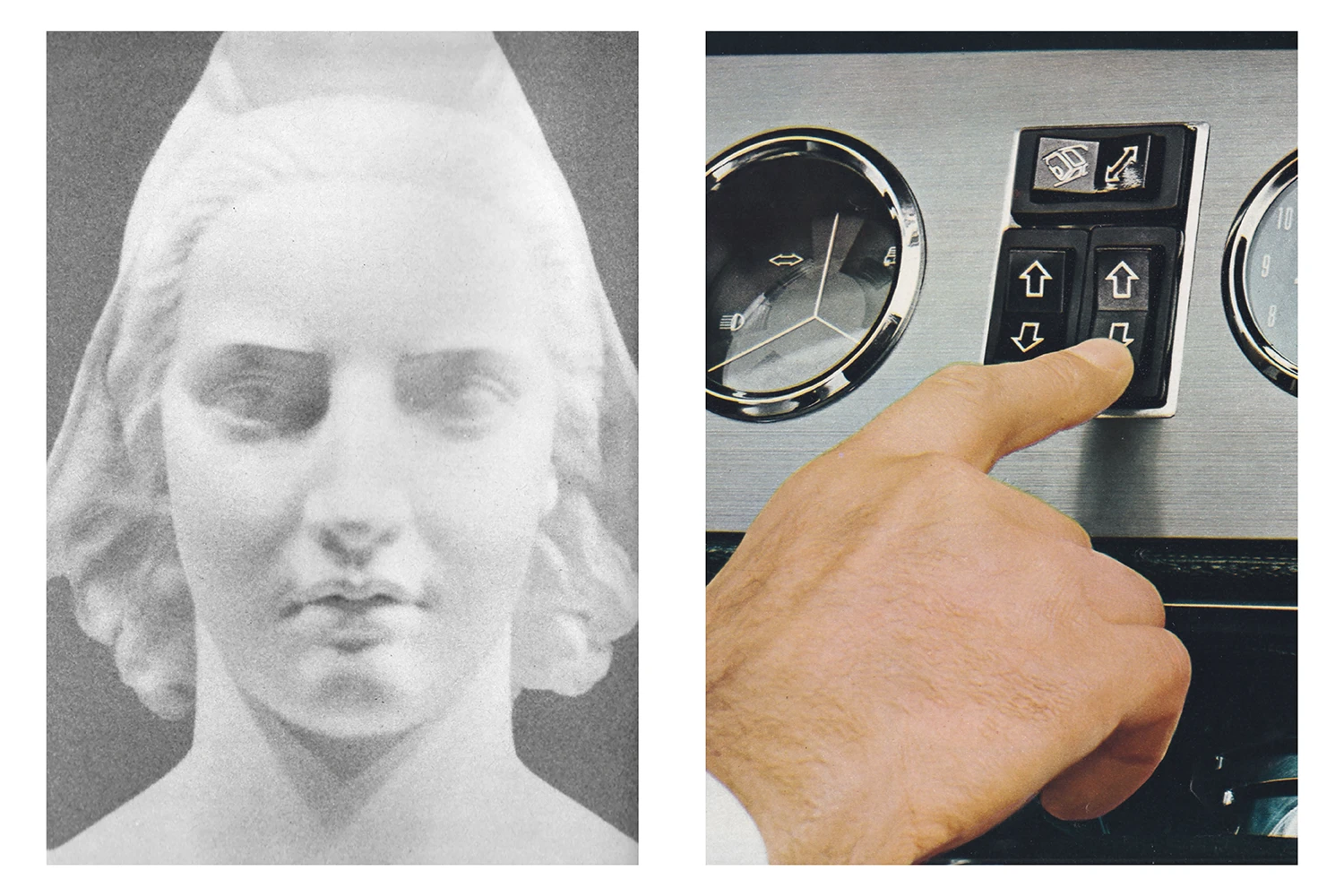

De Ferluc insists that the intrinsic meaning of an image does not disappear, even when it is detached from its original context or reframed by new techniques and critical apparatus. “A photograph of a soldier returning from war or a forest burning carries the same semiological weight. The photo of the forest in flames will always tell the story of a forest in flames. It is a-historical.”

By working with existing material, the artist proposes a circular vision of history, in which peace and conflict, crisis and resolution, revolution and reaction recur. In such a cycle, the question is not whether to produce new images, but which of the countless existing ones are worth retrieving, re-assembling, and transmitting once again.

The ambiguous power of photography between truth, advertising, and spectacle in the 1960s and 70s

At the heart of Augure lies a meditation on the ambiguous nature of photography and its enduring influence on collective imagination. Since its inception, photography has oscillated between document and spectacle, between news and advertising. Paris Match embodied this ambiguity perhaps more than any other European magazine of its era.

Its glossy pages allowed for fluid coexistence: war reportage next to cigarette ads, political analysis next to beauty tips, stories of famine next to Hollywood glamour. For the reader, information and publicity were mediated through the same aesthetic codes. The shock of photography resided not only in what was depicted but also in what was juxtaposed.

Risograph printing and the fragile economy of images: tactility, imperfection, and visual memory

Formally, the project gains depth through its chosen medium: risograph printing. The decision to print Augure on risograph paper reflects a deliberate embrace of imperfection. The technique, with its fragile ink that never fully fixes, mirrors the ephemeral economy of contemporary news and images.

Turning the pages of the book becomes analogous to scrolling through a feed – information consumed with ease and lightness, only to vanish with the next update. For de Ferluc, this tactile, almost sensual engagement contrasts with what he calls the pornographic nature of certain images: those that cease to represent and instead claim to be the very object they depict. Here, the artist recalls Magritte’s lesson: “This is not a pipe.” The distance between image and reality must be maintained if we are to resist the collapse of representation into spectacle.

From augury to prophecy: how Rodrigue de Ferluc uses birds as metaphors of vision and image migration

The title Augure itself evokes the Roman priests who interpreted divine will by studying the flight of birds. In de Ferluc’s book, avian figures weave a thread through the narrative: from a Beatles-haired crested canary on the opening page to a sick owl at the conclusion. Albino birds, migratory birds, caged birds: all become metaphors of vision, prophecy, and displacement.

Like birds, images follow trajectories that exceed human control. They migrate, return, and reappear in unexpected constellations. In this sense, Augure is not simply an act of visual memory but a political gesture: it slices, reorders, and re-assembles fragments of a recent past to suggest uncomfortable parallels with the present. In an age when we scroll seamlessly between commercials and war footage, between influencers and disasters, the book reflects on a paradox of distance: the more images pass before us, the less we feel them.

The bunkerization of imagination: algorithms, image control, and the shrinking horizons of visual culture

The project also confronts the shrinking horizons of contemporary visual culture. De Ferluc draws on Rem Koolhaas’s idea of the “bunkerization of the imagination,” noting how images, once capable of opening onto the world, now often function as instruments of reassurance. Despite their multiplication, algorithms funnel us into ever-narrower clusters of content, reinforcing our values, convictions, and social status.

Images thus oscillate between being tools of democratic expression and instruments of confinement. They can fuel dissent in societies under strict control, but they also enclose us in echo chambers that confirm what we already believe.

At stake is the question of who controls the collective gaze. Historically, the production and distribution of images required large numbers of people and institutions. Paris Match itself was once the work of hundreds of editors, photographers, printers, and distributors. Today, image management has become increasingly centralized, automated, and disembodied. Generative AI systems train on vast databases of pre-existing images – often produced by other AI systems – creating a closed loop whose ecological, economic, and political costs remain largely unexamined.

“Whoever controls the image banks, controls the future,” de Ferluc warns.

Why re-reading old images is the most subversive act in the age of AI and visual overproduction

In this environment, saturated with pictures whose origins are uncertain – whether human-made, documentary, or algorithmically generated – the act of creating new images risks becoming redundant. The real subversive gesture, Augure suggests, lies in learning to read and reread the images we already possess.

The project is, in this sense, both a work of memory and a critique of memory’s mechanisms. It asks us to recognize how images outlive their contexts, how they continue to speak across decades, and how they can be reactivated to question the present. By rescuing fragments from the pages of Paris Match, Rodrigue de Ferluc shows that the value of images is not exhausted by their original publication. Their meanings persist, mutate, and, like auguries, foretell futures we may not yet be ready to confront.

Claudia Bigongiari