Oda Jaune Reclaiming Wings: Angels Among Ruins

Being religious was nearly a crime. At home, my parents trained me to answer school questions carefully, to evade, to feign indifference. No one could know we were believers – everyone watched everyone

Life Under State Surveillance in 1980s Sofia

We had to be cautious. External images were not broadcast on television. We learned about the fall of the Berlin Wall by secretly listening to a German radio station. Everything was monitored. Even the neighbors had to be distrusted.

Witnessing the 1989 Berlin Wall Collapse as a Bulgarian Child

1989. At ten years old, I saw a system crumble. I remember people pouring into the streets, saying, “Now we can speak. It is over.” Everyone was crying, gathering with candles, talking to one another. The fall of the regime brought euphoric freedom. Soon euphoria turned to chaos. The war in former Yugoslavia erupted. We had no bread. Electricity was rationed — one hour, two hours a day, sometimes none. No heating.

Emigrating to Heidelberg: Early Challenges for a Young Bulgarian Artist

My mother and I left for Germany, leaving my father behind in Bulgaria. Leaving was not easy. In order for me to go, my aunt, who lived in Germany, had to legally adopt me. (Years later, we annulled the adoption, and I once again became my parents’ daughter.) We settled in Heidelberg.

Cultural Misunderstandings in the German Classroom

One day I arrived at school with plastic markers I had received as a Christmas gift. I wanted to show the other children what I could draw — especially since I did not yet speak German well. They forbade me from using them. They did not understand. They said plastic was harmful — which was true — but they failed to grasp what those markers represented for me.

At that time, not only did I speak German poorly, but I also lacked fine clothes. My sister had given me hers, mostly in black and navy blue, while the other children wore pink and orange. Some German girls remarked, “You’re a little dark; you shouldn’t dress in black,” and gradually, I started falling ill more and more often. My parents realized I was unhappy, and they decided to send me back to Bulgaria.

Returning Home: Bulgarian Art School Foundations

When I returned to Bulgaria, I joined a small specialized school for young artists, where we studied music and philosophy. Later, I continued my studies at the Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts, where my sister was already enrolled. This type of education did not exist in Bulgaria — doors were open, visitors could enter and observe the students’ work. I remember the way people looked at the artworks.

There is nothing more honest than that gaze. The way they moved, paused in front of a piece — those reactions spoke volumes. Open exhibitions allowed us to see those responses as if conducting an experiment. Children reacted instinctively — if an artwork evoked something in them, they would show it without any filter.

Düsseldorf Academy Insight: Safeguarding Artistic Integrity

Our professors warned us: “We know you need money, but be careful. Your soul must always come first.” Collectors were present, but we were advised not to rush. In the beginning, one is vulnerable. Chance plays a role. If one can create without showing their work to anyone for as long as possible, that is best: to make art for oneself, in secrecy, and then one day, decide to open that door.

My father used to say, “If you ever need money, never compromise your art. Find another job.” I have inherited that Bulgarian resilience. I am aware that I can endure more than others, push beyond imposed limits. I was taught to be wary of rules, not to follow blindly. Everything must be done my way.

Mother’s Strength as a Motif in Oda Jaune’s Work

I can adapt to anything, create from nothing. My mother may have always been present in my work without my being fully aware of it. For six months, I knew exactly what I wanted to paint, yet I was unable to do so, bound to the hospital at her side. She was ill.

My mother is endowed with unshakable strength. I remember a flight we took when I was a child. The plane nearly crashed. Around us, passengers were screaming. My mother turned to me and said, “This is the moment to be grateful. Life has been beautiful.” Then, when the plane eventually stabilized and we were saved, she simply smiled, as if nothing had happened. I have never seen my mother cry — except when she listens to classical music.

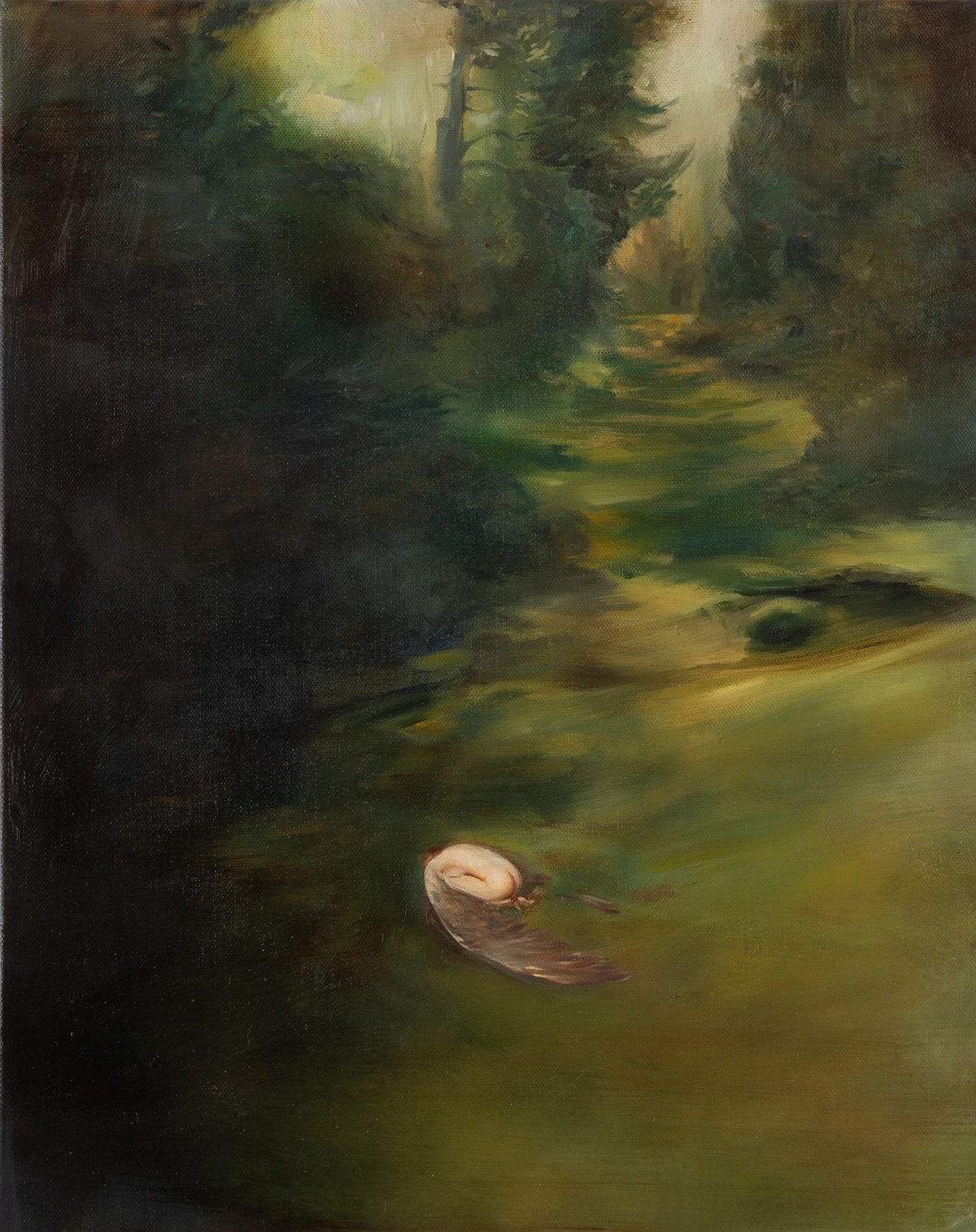

Wing Imagery: Freedom & Transformation in Contemporary Art

Age, transformation, what we gain and what we lose. And then, there are these wings that fascinate me: breathing underwater, being as light as light itself, rising and soaring. I often wonder: What happens to those who once had wings but have lost them? Why do we not have feathers?

Childhood Flight Experiments: Pain and Growth

As a little girl, I tried to fly. On a swing hanging from an apple tree, I asked to be pushed, convinced that I would take off. Then I jumped … and the pain was sharp, as if I had abruptly halted my own growth. One day, when I was six or seven, I was certain I could fly. I leaped from the first floor.

Influence of Sofia’s Mountains & Countryside on Creative Vision

I was born in Bulgaria and grew up in Sofia, in the heart of the city, until the age of twelve. Every weekend, we would leave for the countryside, where we had a villa. There, I was often alone, surrounded by trees. That is where I began sculpting. I have always painted, always created, in that solitude that lived within me. Sofia is a city nestled between two mountains. In winter, they are draped in a white mantle of snow, while in summer, the heat is overwhelming. Between these mountains, the air seems trapped, laden with dust.

Father’s Teachings: Anatomy, Color Theory & Perspective

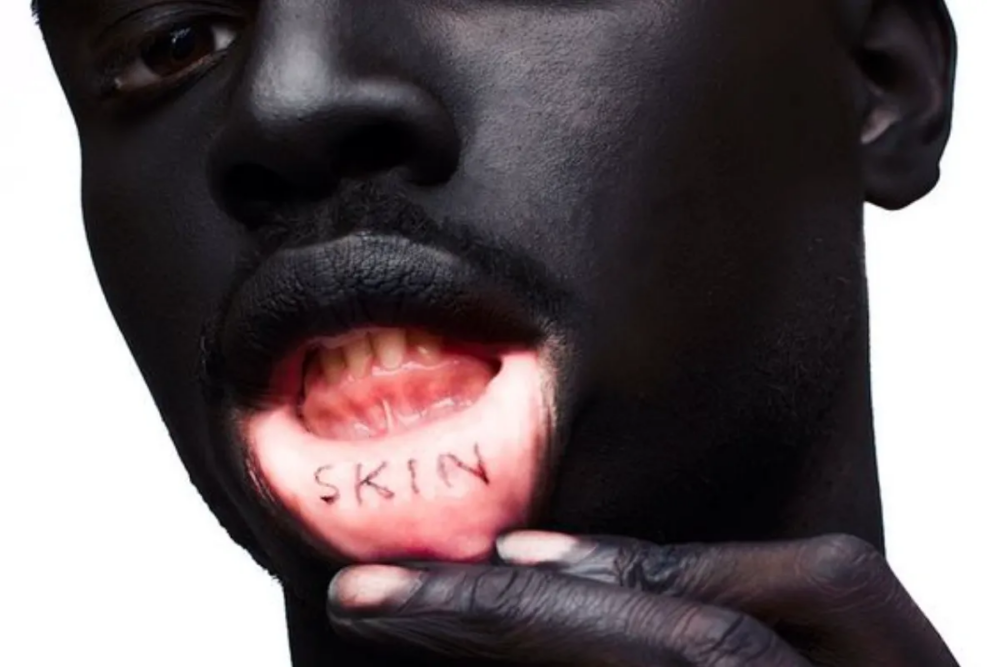

With my father, we would take long walks in the forest. We set off, a sandwich in hand, talking as we walked, and then we would return. He would say to me: “Look closely. Every tree is different. No two are alike.” He believed that all answers could be found within the human body.

He would tell me that one must understand anatomy — one cannot comprehend the skin without knowing what lies beneath it. He spoke to me about painting, showing me how every color can be warm or cool depending on what it is paired with. “If you do not choose the line, then light and shadow will define it for you.” Where light meets shadow, a boundary is born — a line. Everything is a matter of contrasts. He spoke to me about perspective, not only in art but in society as well. To change a proportion is to change a message.

Matchstick Lessons: Simplicity Before Complexity in Art

My first lessons were a game. He taught me to see using matchsticks, to rearrange them in order to grasp the simplicity of movement. He told me that if one truly masters the simple, one need not fear complexity. “You can abandon everything,” he would say, “but only if you know exactly what you are leaving behind. You may venture into abstraction, but only if you are not afraid of the figurative.”

Choosing Light Over Pure Abstraction: Artistic Philosophy

Abstraction, to me, is an absence. It does not interest me. I am fascinated by light. My father loved the earth, painting, and ceramics. He worked with ochres — deep, warm colors, very different from mine. He did not paint to exhibit. He painted for himself. His profession led him to create for others — graphic design, decorative arts, advertising photography — but his art remained intimate. His studio was his kingdom. At the top floor of our home, it was his space, his refuge.

Everything had its place — unlike my own chaos. I wanted to touch everything. Sometimes, I forgot to close the jars, and he could no longer use the paints. He was fascinated by Egyptian civilization. He spoke of the Greeks, comparing them to the Romans, explaining their legacies. His love for these civilizations was immense, imbued with admiration and reverence. To him, they represented the highest elevation of the human spirit, the nourishment for the mind. Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci. We traveled together to Rome, to the Vatican. I was fourteen, fifteen, sixteen years old.

First Oil Paintings: Socialist Realism Blends with Greek Mythology

My first oil on canvas was a blend of socialist realism and Greek mythology, highly idealized, influenced by Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People. I began oil painting at fourteen. Before that, I had explored tempera, watercolor, and pastels. I did not like ink or line drawing. Watercolor and pastel powders appealed to me more — soft and fluid materials.

Parents’ Love Story & the Bulgarian Academy of Fine Arts Challenge

My mother was from Plovdiv, the ancient capital of Bulgaria. She arrived in Sofia as a child, and my father at eighteen. They met at Balkan Air. My father fell in love with her instantly and asked her to be his wife. She hesitated. So she gave him a challenge: get accepted into the Academy of Fine Arts; quit smoking; find a gold ring. At that time, gaining admission to the Academy was nearly impossible. Most places were reserved for the children of Communist Party members, with only two or three genuinely open spots. My father succeeded.

Anna Berest