Who’s afraid of the father? Camille Lévêque rewrites paternal mythologies

Through collage, family archives, advertising images, and political propaganda, photographer Camille Lévêque dismantles the traditional father figure, exposing patriarchal myths in À la recherche du père

The fragile myth of fatherhood in culture and society

The figure of the father has always been a fragile and contradictory archetype. In Western tradition, it has been overloaded with responsibilities and expectations: a moral guide, economic pillar, protector, but also a distant authority, sometimes violent or entirely absent. A role both idealized and feared, which extends far beyond the family and into political and cultural realms. The father has been narrated not only as the head of the household, but also as the father of the nation, a guarantor of order and symbol of stability.

It is within this complex landscape that Camille Lévêque’s decade-long project unfolds. À la recherche du père began in 2014 as a deeply personal inquiry and gradually expanded into a polyphonic archive of voices and images. Through collage, family albums, testimonies, and advertising iconographies, Lévêque constructs a plural portrait of fatherhood: not as a monolithic presence, but as a cultural invention that must be interrogated, fragmented, and rewritten.

Family archives and fragmented memories: when the father figure is missing

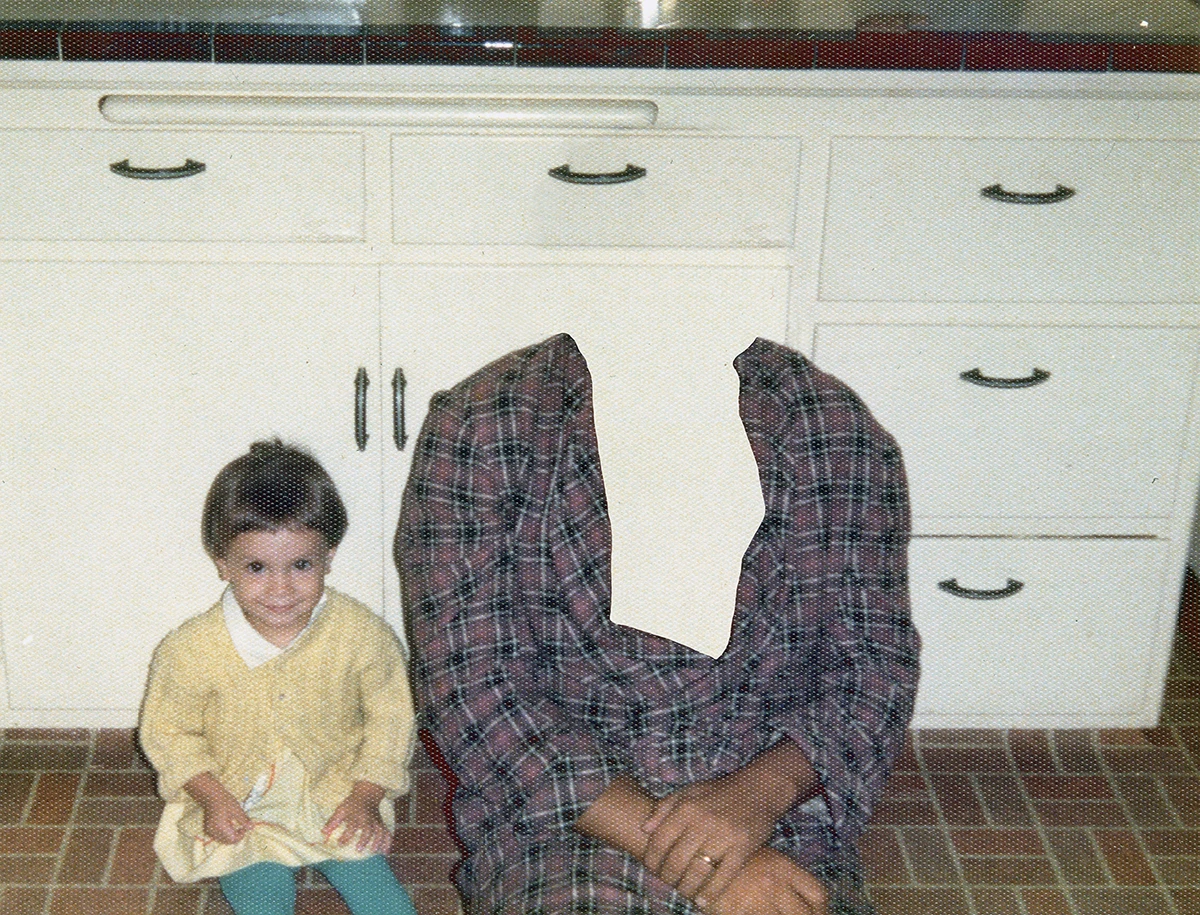

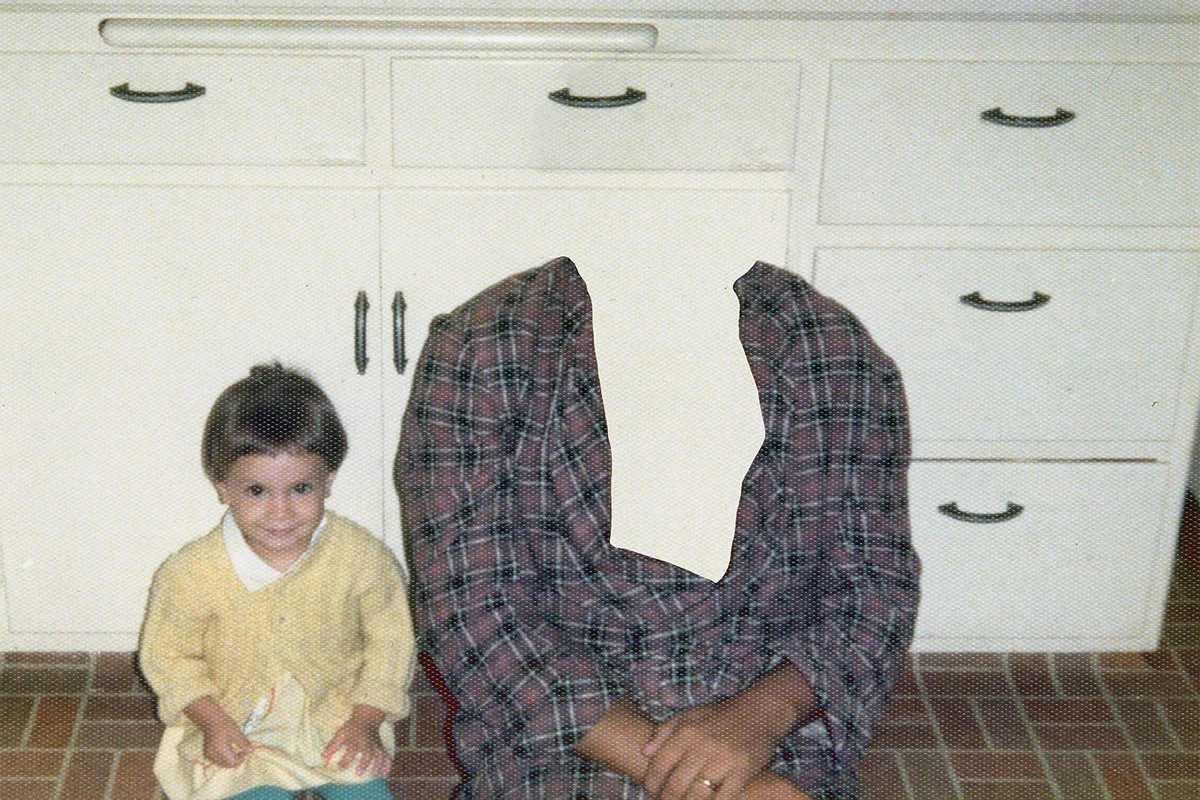

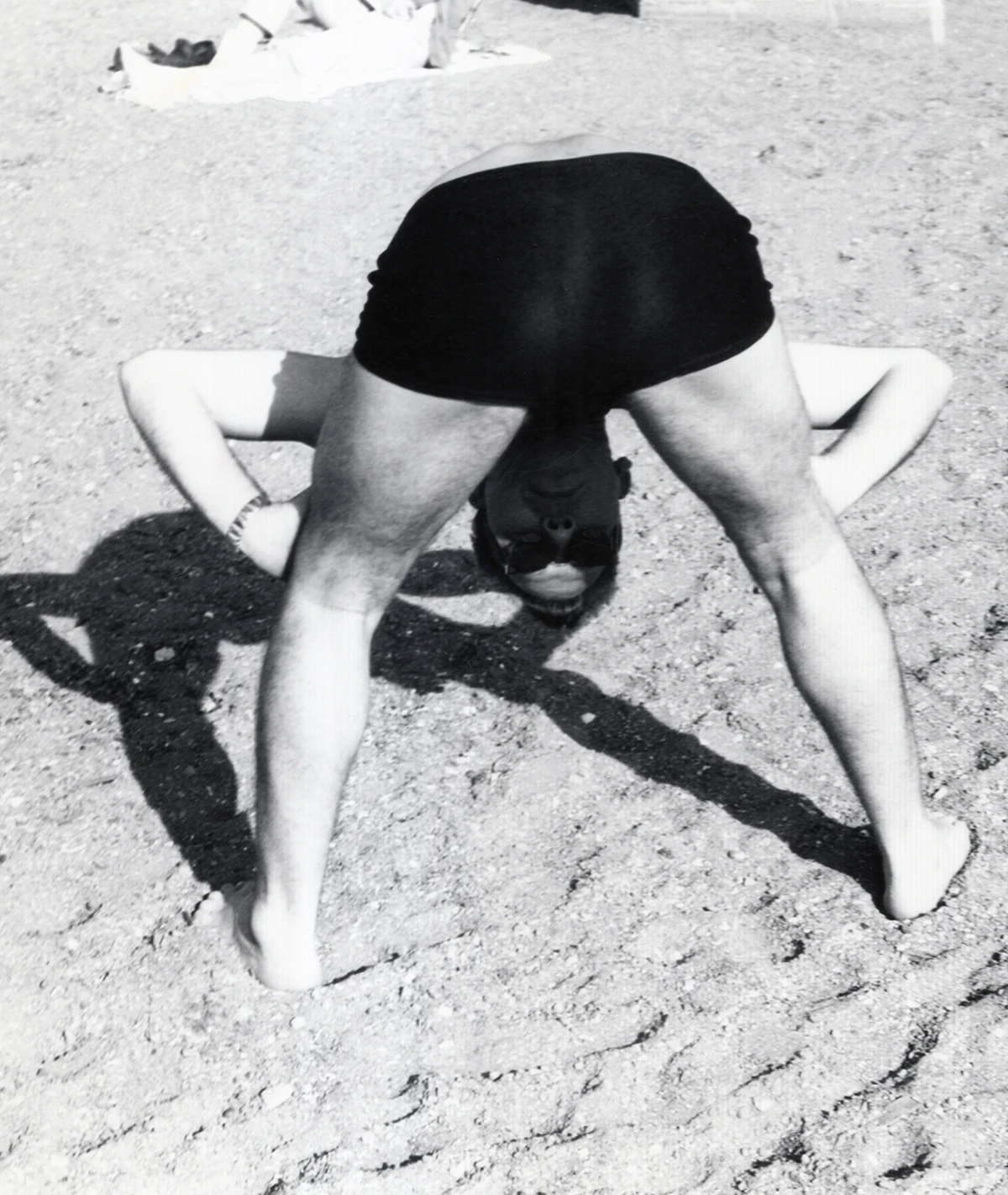

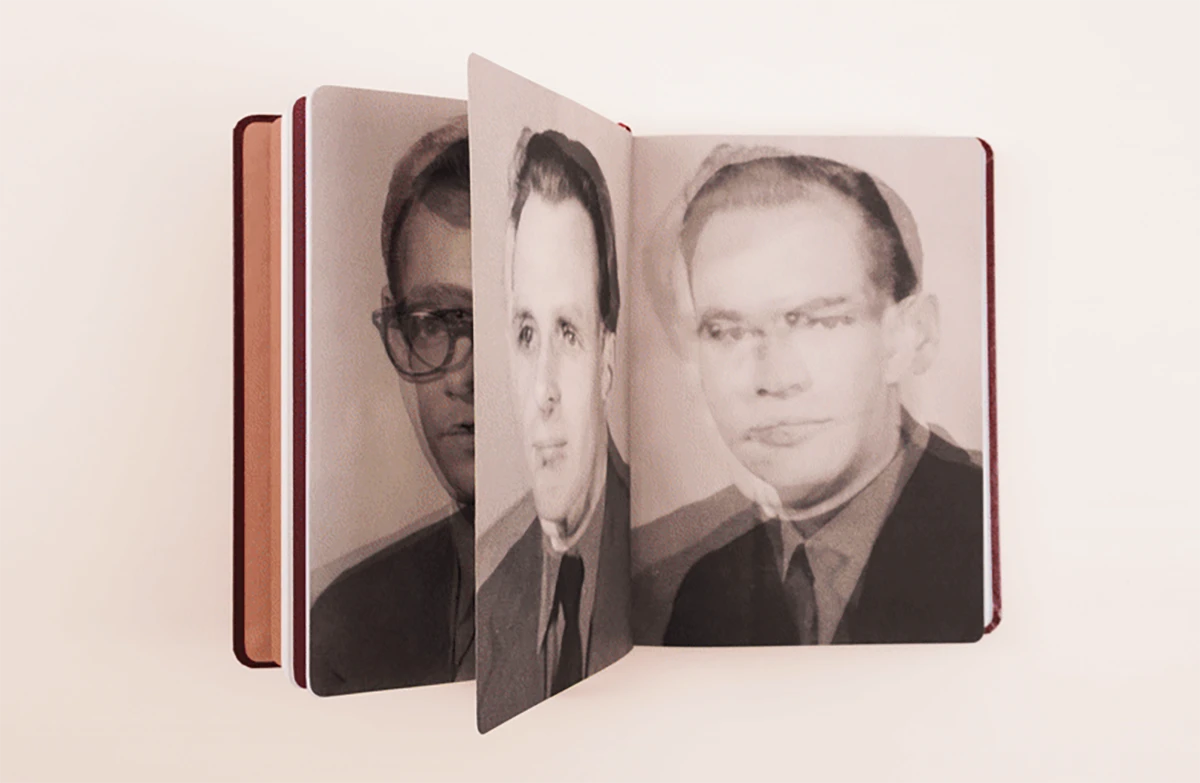

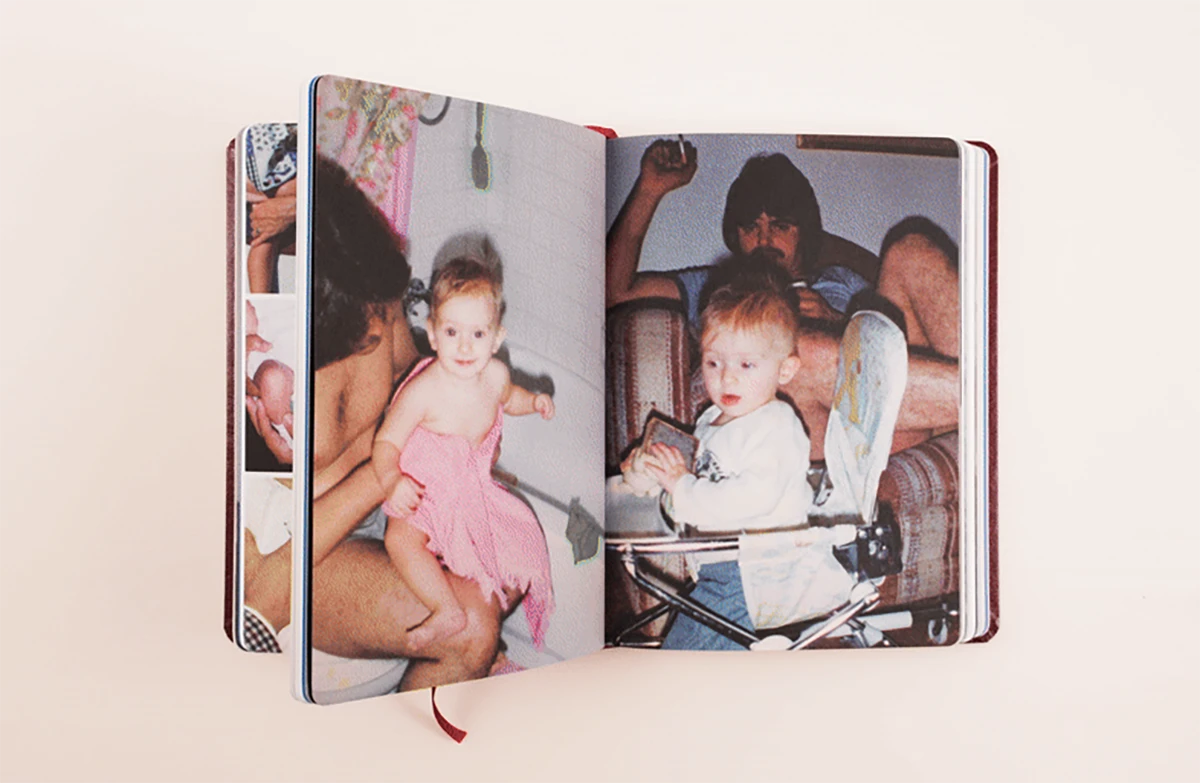

Lévêque’s work begins with a radical yet intimate gesture: reopening the family photo albums. In her visual memories, the paternal figure appears blurred, absent, cut off at the edges — heads cropped, gaps left blank, traces erased. This is a father who fails to hold shape, leaving wounds rather than presence.

From this autobiographical nucleus, the artist expands outward. She invites others into the project: sex workers, religious figures, daughters and sons of absent or overbearing fathers, voices from different cultural contexts. In each testimony she encounters the same silence, the same ambivalence. À la recherche du père becomes a collective archive, where paternal absence repeats itself across lives and generations. “Personal memories emerge as layered and elusive traces, offering a mirror in which ambiguity can be shared,” explains Lévêque.

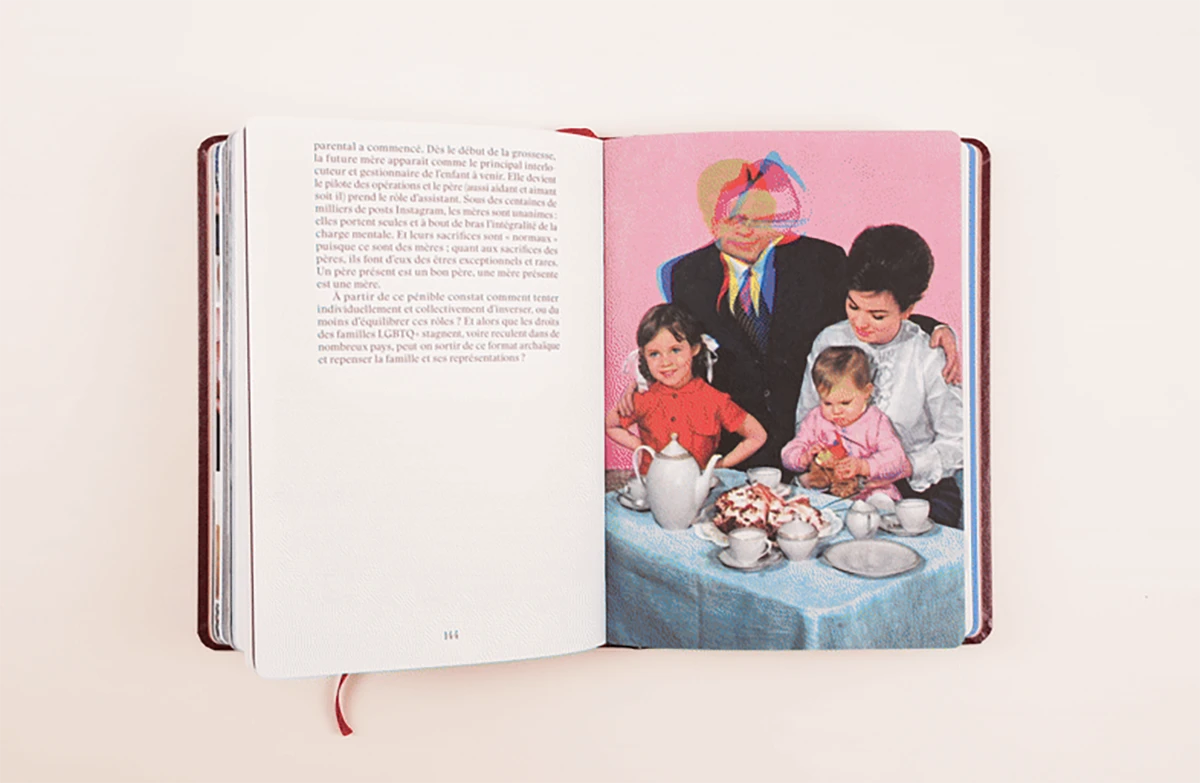

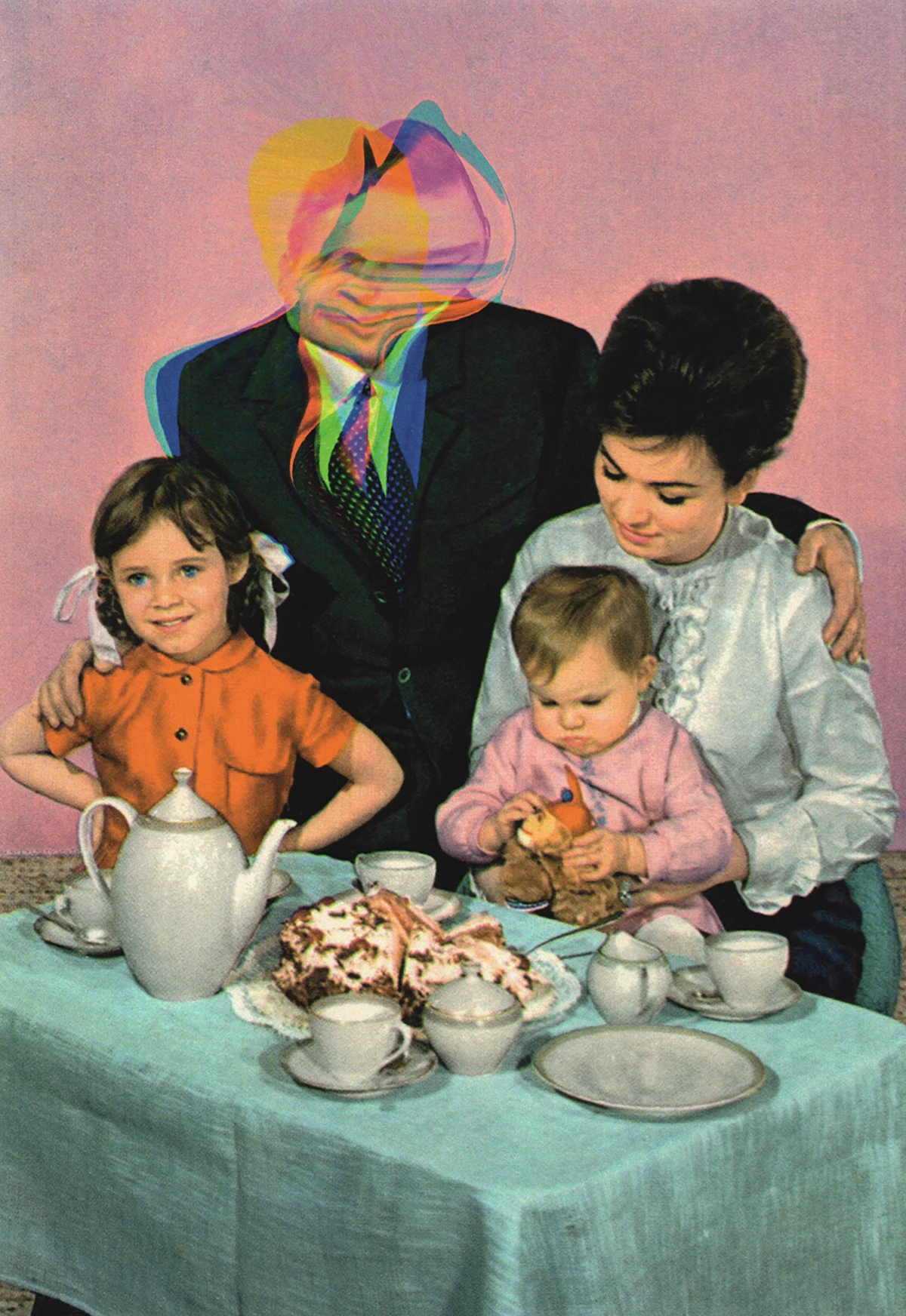

Collage as a language of honesty: raw aesthetics against patriarchal authority

This uncertainty finds its form in the materials and methods Lévêque chooses: rough collages, glitches, erasures, superimpositions. A visual language that refuses smoothness or linearity. “It is a material response to emotional trauma,” she states.

Her collages recall the instinctive cut-and-paste creativity of children building imaginary worlds. Yet behind this apparent playfulness lies a critical stance: embracing error, rupture, and instability as integral to storytelling. Far from polished aesthetics, Lévêque’s works convey a fragile, emotionally unstable memory — one that feels more authentic than any glossy depiction of family life.

The breadwinner archetype: how advertising built the ideal father figure

Alongside private archives, Lévêque interrogates the visual culture that shaped fatherhood throughout the twentieth century. In the 1950s and 1960s, Western advertising consolidated an apparently unshakable model: the man as breadwinner, tireless worker, and financial provider for the family.

Television commercials and magazine spreads endlessly repeated the same script: the father returning home after work, greeted with his wife’s smile and a warm meal, rewarded for his dedication. This language reinforced a strict hierarchy of roles — man as authority and guarantor of stability, woman confined to the domestic sphere.

These images, consumed and reproduced for decades, implanted themselves deep in the collective unconscious. The father as pillar of stability became not only an ideal but also an invisible enforcer of gendered hierarchies.

From household patriarch to father of the nation: politics and paternalism in the 20th century

Advertising was not the only medium to codify paternal authority. The archetype of the father also became a political instrument. Throughout the twentieth century, leaders from Charles de Gaulle to Stalin, Mussolini, and Franco sought to embody the father of the nation.

The image was strikingly consistent: the ruler as protective guide, provider of safety, the patriarch who knew best for his citizen-children. But behind the rhetoric of filial affection lay a relationship of obedience and submission. Fatherhood was deployed as a tool of collective discipline, naturalizing hierarchies and legitimizing authoritarian rule.

In this light, fatherhood never belongs solely to the private domain: it is a political construct, a mechanism that organizes social relations.

Psychoanalysis and archetypes: the symbolic function of the Name-of-the-Father

Psychoanalysis has also helped cement the father as a symbolic anchor. Freud conceptualized him as the bearer of law, the figure who introduces the child into society. Lacan advanced the idea of the Nom-du-Père — the “Name-of-the-Father” — a symbolic rather than biological function, embodying law, authority, and prohibition.

This framework shaped generations: the father as the one who forbids, who sets boundaries, who represents necessary distance. But what happens when this figure weakens, disappears, or is replaced by other models of care? Lévêque’s work seems to probe precisely this void: what remains when the symbolic father no longer holds?

Generational trauma and patriarchal inheritance in contemporary families

Behind the myth of the father as protector often lie scars and violence. Abuse, abandonment, authoritarian control — traumas passed from one generation to the next, embedded in social structures.

“I would like to see individuals and communities re-imagine fatherhood on their own terms — beyond trauma and inherited archetypes — to create a new constellation of care, authority, presence, and absence,” says Lévêque.

Her research becomes an act of healing: dismantling myths of the past in order to open new possibilities, where fatherhood is no longer synonymous with power or lack, but can be re-invented as a more fluid, vulnerable relation.

Fathers on screen: from sitcom archetypes to postmodern parodies

Cultural representations of fathers are not confined to family albums or political rhetoric; they are pervasive across cinema and television. In the 1950s and 1960s, American sitcoms consistently portrayed the father as the benevolent authority — wise, calm, and always restoring household order.

By the 1970s and 1980s, this figure began to fracture. Cinema presented absent fathers, abusive patriarchs, or men in crisis. Today, series and films frequently show fathers as vulnerable, uncertain, sometimes even mocked. Popular culture thus mirrors a broader shift: fatherhood as a fixed role no longer holds, and instead appears fragmented, unstable, even parodied.

Feminist critiques of fatherhood and the dismantling of patriarchy

Feminist theory has long questioned the centrality of the father as institution. Patriarchy has been denounced as a system of domination that excluded women from the public sphere and positioned the father as guarantor of gendered hierarchies.

Lévêque’s project resonates with this critique. By dismantling the myth of the father, she also destabilizes the symbolic foundations of patriarchy. Her collages are not only personal recollections but also political gestures that reveal the artificial nature of paternal authority.

A photobook as secular bible: À la recherche du père in print

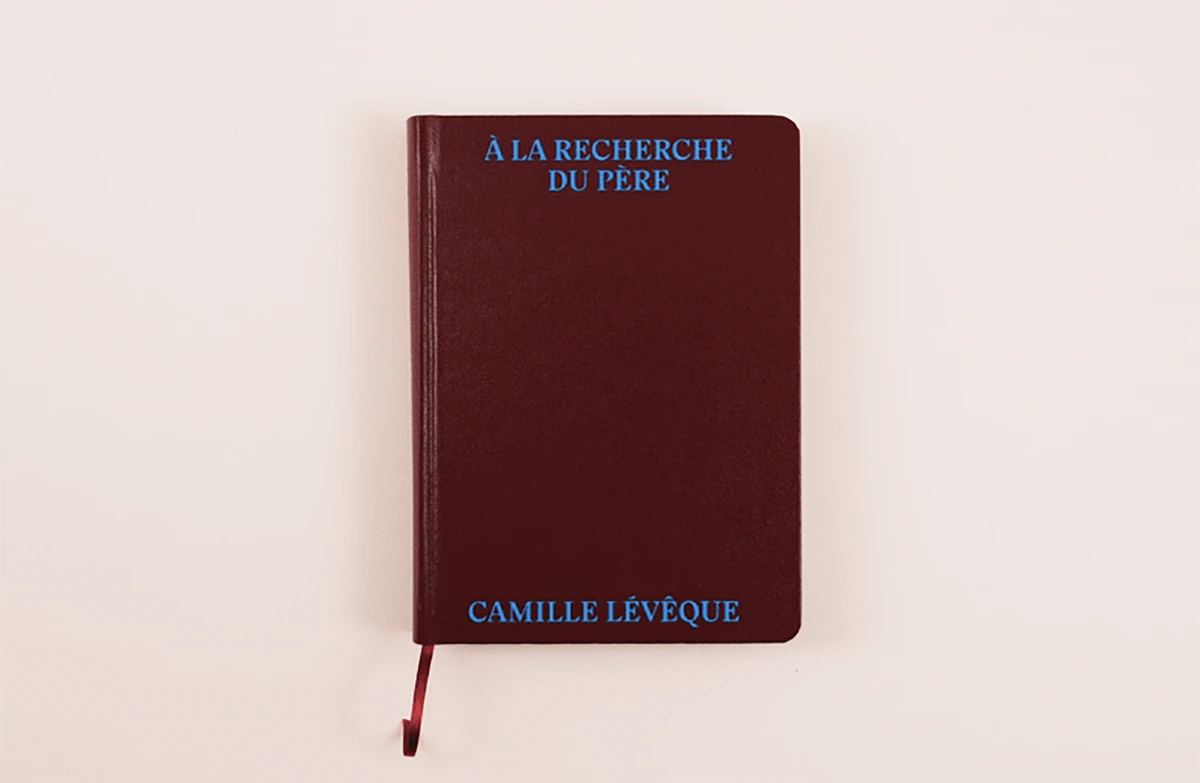

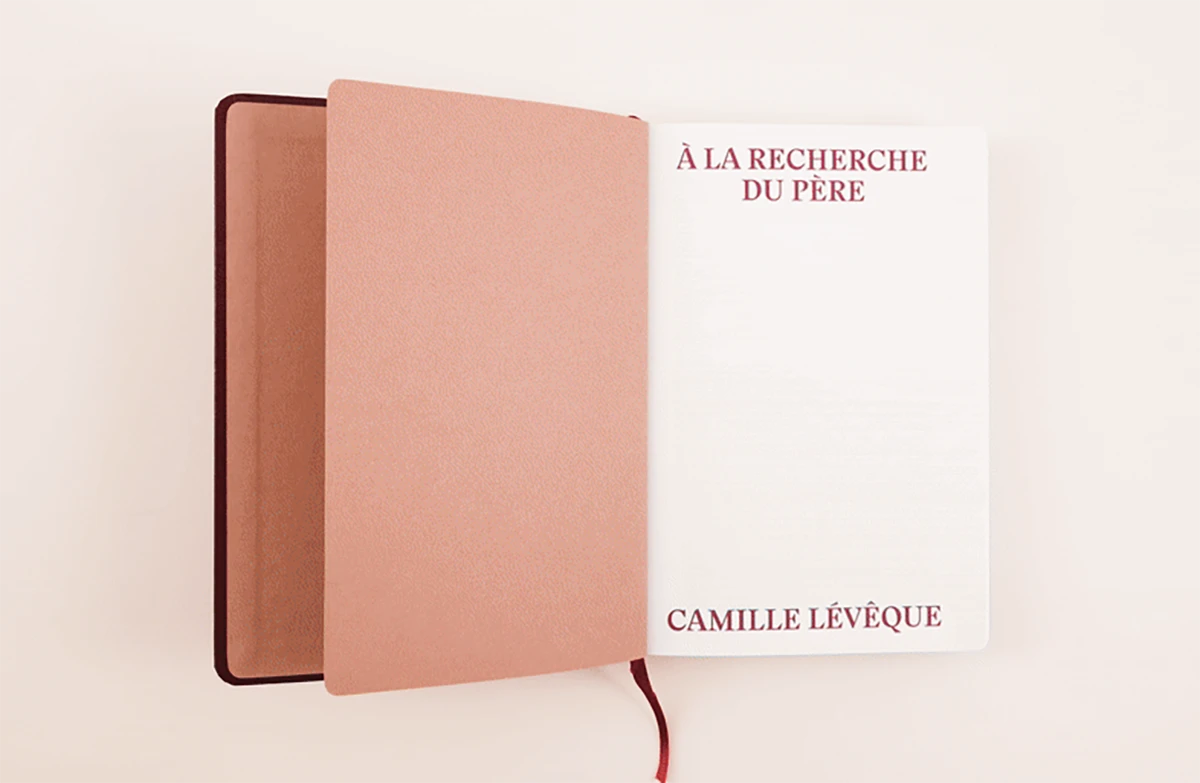

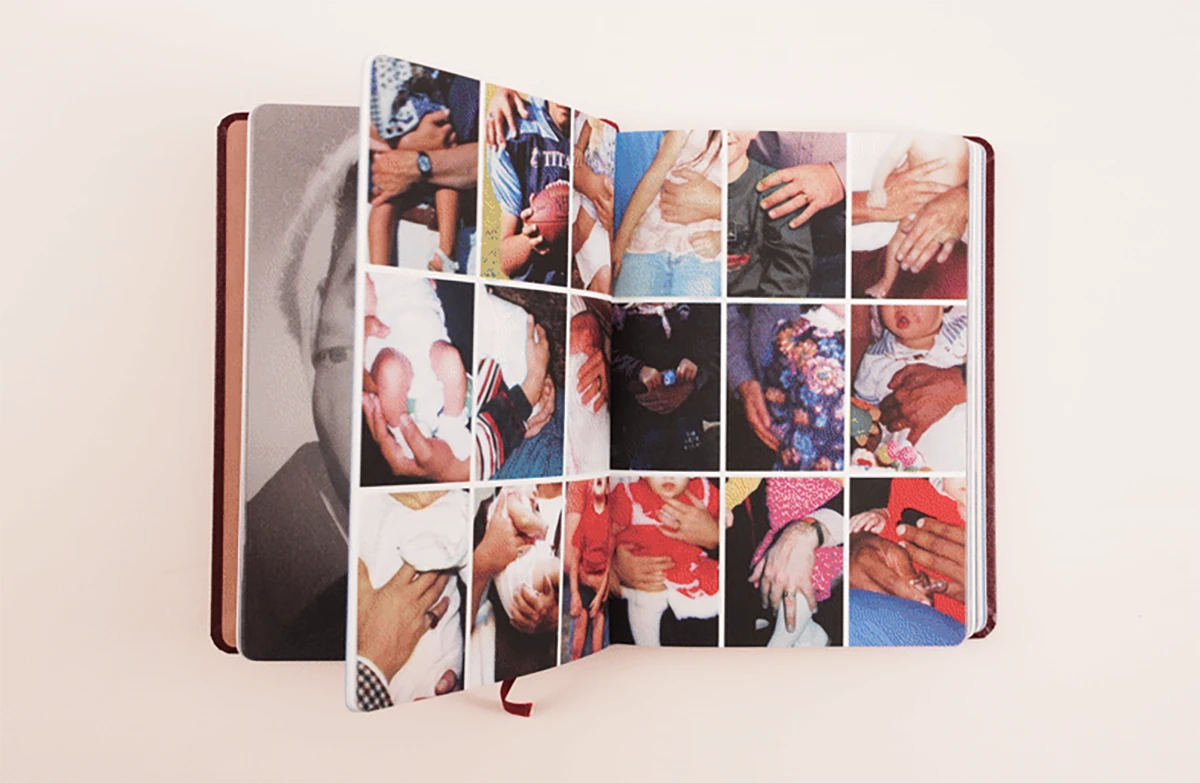

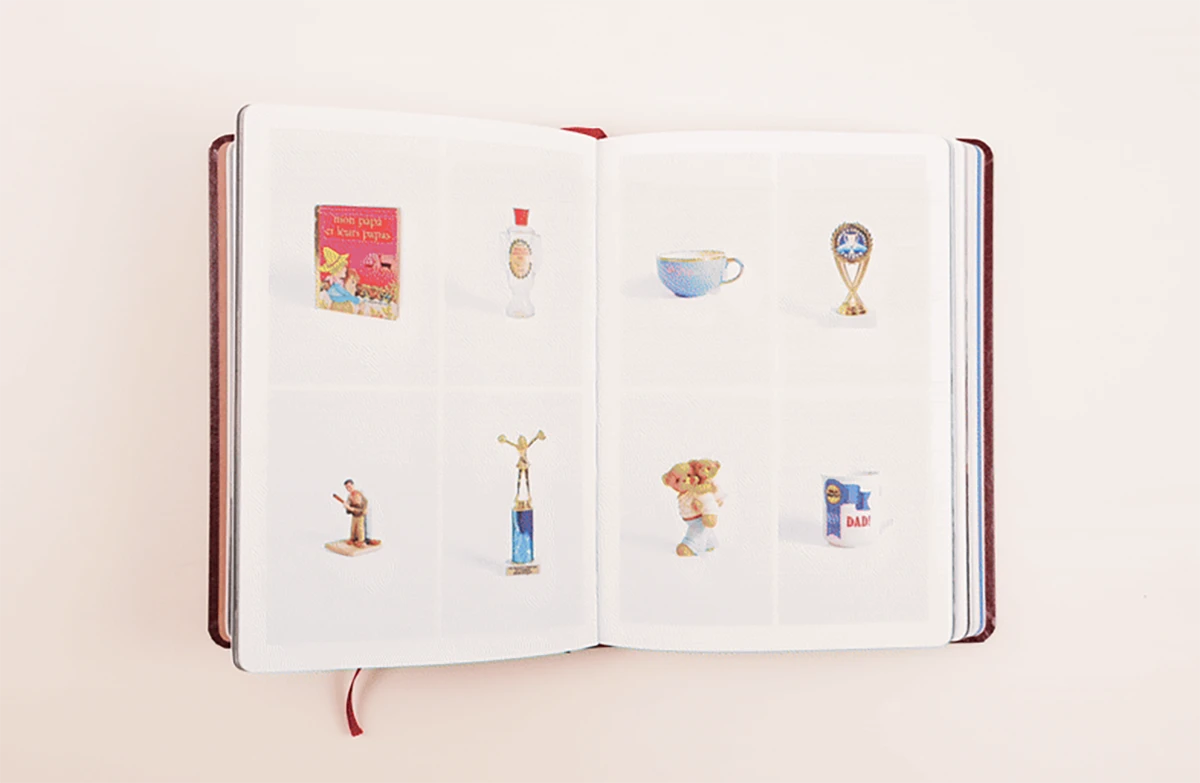

The project found its material form in the photobook À la recherche du père, published in 2025 by Delpire & Co. Small in scale, bound in faux-leather hardcover, the book deliberately resembles a bible. Yet inside there is no dogma, only fragments: photographs, letters, advertisements, collages, objects.

“Designing the book was an act of translation, from a vast archive to an intimate object. I arranged images and texts as if they were a sculpture — not to commemorate an illusion but to guide the reader through an emotional navigation,” explains the artist.

Nonlinear and open-ended, the book resists spectacularizing trauma. It is not a narrative to consume, but a companion to wander through, where each reader chooses how to connect with its fragments.

Visual honesty and sustainable images: resisting the commodification of trauma

In today’s cultural landscape, trauma is often transformed into consumable content, aestheticized for mass circulation. Lévêque moves in the opposite direction. She recycles visual materials, embraces rawness, and refuses to polish or sanitize the images. The wounds remain visible.

“We live in a time when trauma is monetized, aestheticized. I believe photography can still sustain a space for authentic reflection if it rejects glossy surfaces and accepts ambiguity, error, and raw matter. That is how we can speak of healing without turning it into entertainment,” she affirms.

Claudia Bigongiari