It’s Prada, Prada again, always Prada. Why are we so obsessed? It’s that sense of balance

In fashion, obsession means Prada. How does Miuccia Prada, also in dialogue with Raf Simons’ cool detachment, continue to rediscover—and redefine—the identity of Milan?

Prada and the measure of Milan

The keyword is “balance”. Not style. Not taste. Neither the aesthetic identity—nor the method. If there is one word that can tentatively summarize the work of Miuccia Prada, that word is “balance”.

A vain exercise, perhaps. As vain—and as sterile—as writing yet another review of a Prada show (and how many more I will write). “Balance” is not knowing what to choose; it is knowing how much to choose. You find the right “balance” only when you know how to do what you want to do.

“Balance” is also the code of an intellectual Milan that resurfaces when we think of our architectural masters—Ignazio Gardella, Gae Aulenti, Franca Helg – how many more, the Italian main references. “Balance” is the design, it is never decoration. You find balance when reading a Ferruccio De Bortoli editorial; in the line of Forattini, in Emilio Tadini, in Tullio Pericoli. It’s all so Italian. In Italy we should do one thing—and do it well. With Prada, the balance becomes visible. It becomes the identity of Milan.

Unlike other fashion houses—where the direction is so linear that it turns almost didactic, where commercial pressure risks flattening creativity—Prada remains unpredictable. You never quite know what will walk down the runway. And yet, season after season, show after show, it is immediately clear: this is Prada. Only Prada. Still Prada. Always Prada.

Fondazione Prada, TikTok, Hollywood, Kendall Jenner

If Prada did not exist, Milan would have a problem. Those of us who endlessly search for the city’s identity would be lost—pointless, even. Prada is a reference point: a benchmark, a reassurance.

The culture Prada produces—also through Fondazione Prada—is complex, difficult, elitist, not inclusive. And yet, that same culture supports a company whose revenue continues to grow. Which means one thing: human beings are not condemned to the simplification of TikTok.

As an aside, Hollywood seems to be moving in the opposite direction. Data suggests audiences are more distracted than we once were; today, even while watching a movie, people feel compelled to check their social feed. Scripts adapt accordingly: not architectural narratives, but stories designed so that if you lose focus for five minutes, you don’t lose the storyline . You can jump back in without consequence.

Closing the parenthesis—Prada reassures us. It is not true that refusing to adapt to a new neural infrastructure—where social media acts as plumbing—makes you a sterile nostalgic. Both Miuccia Prada and Lorenzo Bertelli have spoken about how the sense of belonging—the community—that many of us feel around Prada is generated precisely through Fondazione Prada’s cultural effort. Difficulty, complexity, and sophistication created affiliation.

Without becoming dogmatic—Prada knows how to pull commercial levers. Culture is good, but products must sell. Before the Chiara Ferragni controversy, the influencer was invited by Prada (rumor has it la Signora was less than enthusiastic, while new management insisted). Kendall Jenner ad campaigns follow similar mathematics—different weights, same equations. Much of an industry obsessed with Prada sneers at these lapses in coherence. The irritation passes quickly—like a July downpour.

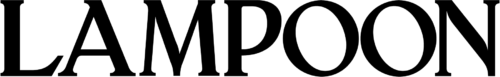

Prada Men’s FW26: the ephebic boy

Two days ago, Prada presented its Men’s FW26 collection—the clothes that will reach stores next autumn. The ephebic boy becomes a manifesto of fluidity. And yet, within the collective imagination, it is difficult to picture la Signora in dialogue with that fragile, slender child—one who may not yet even have body hair.

She is the bourgeois queen in mid-heel pumps and knee-length skirts; the woman who transformed female discomfort and shyness into proud, commanding beauty. The Prada woman could snap the arm of a construction worker after teasing him. The first look of the show is a sexless angel: a long, double-breasted coat that could walk on its own.

And here, “balance” reappears. This is not about the ephebic boy. It is not a political statement, nor a polemic on gender difference in an era exhausted by cancel culture. It is about designing a coat that fits—on a man or a woman—in the correct sizes. The imagery is contemporary; the measure is familiar. A decent boy. One you’d turn to look at if he walked beside you—because you’d want to dress like him. Then comes the styling: shirt cuffs spilling generously from tailored sleeves, oversized enamel cufflinks that could just as easily be earrings.

Prada’s front row: from Stefano Boeri to Troye Sivan

Everything is measured. Even the sharp smell of new, clean plastic that hits you at the threshold of Rem Koolhaas’ atrium. The music. The pace. The front row itself: Stefano Boeri, Troye Sivan, Nicholas Hoult, Mahmood. Men. Human beings with masculine attributes—valid in aesthetics, sensuality, and presence. Prada’s measured balance lies in mixing high and low, pop and snob. The same balancing act we attempt at Lampoon—trying to intercept meaning in a world overwhelmed by digital stimuli.

Outside the venue, to the left, housing for the Olympic Village. Straight ahead, the construction site for the Scalo—a tower still unfinished. Milan feels the crisis. And we, Milanese people, feel discomfort. We need the balance la Signora taught us—and she continues to repeat.

We wake up in a city that welcomes millionaires and lets the homeless freeze. This could be dismissed as romantic pathos—every major city is like this; you can’t change the world. You’re just writing, again and again, yet another Prada review.

And yet. Fashion needs politics—not frustrated discussions about sex. Not politics of parliament or Greenland, but politics as the ancient Greeks understood it: the affairs of the polis. The city. Collective life that cannot be based solely on profit—or worse – on digital self-satisfaction.Still Prada. Always Prada. Once again Prada. We are obsessed with this measure la Signora carries in her eyes and neural circuits—to our great fortune. We imagine her smiling as her ephebic boys walk the runway—boys she may not fully understand, but who are impeccably dressed, she admits. We imagine that trap song in her head—the one played for her the other day to explain who Troye Sivan is. She might have laughed. We like to picture her with a glass of champagne in hand, amused when they showed her how good Troye Sivan’s dance moves are.

Carlo Mazzoni