Rainbows in Shadows by Jenna Gribbon: seeing and being seen

Jenna Gribbon’s first solo show in Milan challenges the definition of looking, inviting the viewer to step into the artist’s place and inhabit her subjectivity

Jenna Gribbon’s first solo show in Milan

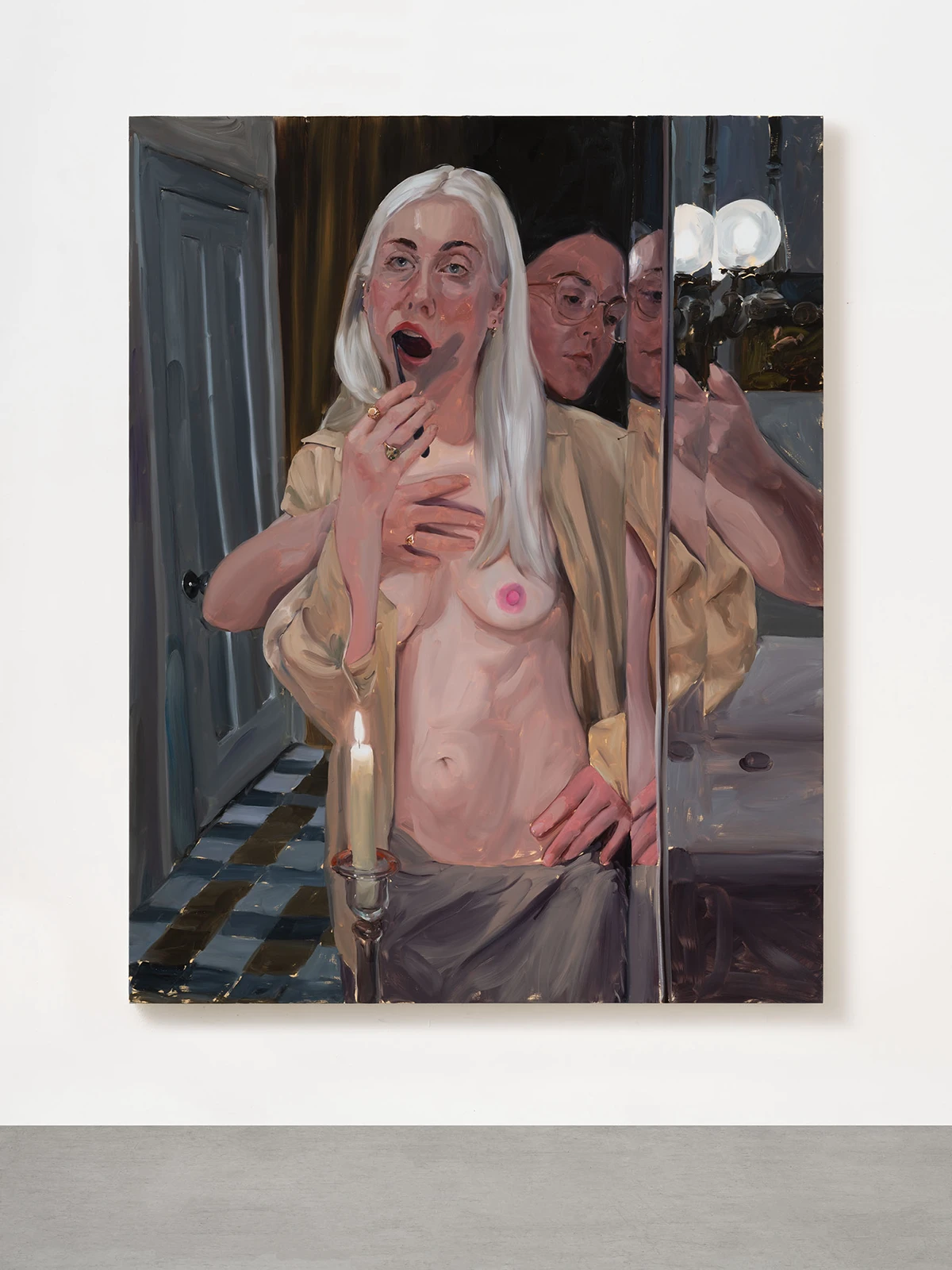

Jenna Gribbon’s first solo show in Milan, titled Rainbows in Shadows, opens on June 5th at MASSIMODECARLO Milano and runs through September 6th. The exhibition is a continuation of Gribbon’s earlier works as well as an exploration of previously explored themes—the private, loving intimacy of domestic spaces; the beauty of queer family; the construction of home as a refuge. It is no coincidence that the show takes place at Casa Corbellini-Wassermann in Milan, a formerly domestic space built in the 1930s by Italian architect Piero Portaluppi. The house, once a residence, has since become a place of artistic refuge and inspiration.

In Rainbows in Shadows, Gribbon’s subjects are once again close to home—her wife Mackenzie, her son, Silas, and herself. She depicts the self as seen from her subjective, yet limited, viewpoint, as something that appears fragmented and incomplete. Only when mediated—when seen through projected images, such as mirrors, shadows, or photographs—can the self appear in its totality. These doublings, as well as the re-emergence of projected images and reflections, destabilize the viewer’s experience of reality, intensifying their knowing and seeing. It might be understood as an extension of reality, an illusion, or perhaps a magic trick. But Gribbon leans into this slipperiness, asking the viewer to reflect on the impenetrable elusiveness of the other’s true self.

We spoke with Jenna Gribbon about the role of her narrative eye, the aesthetics of beauty and intimacy, and the gaze dynamic between viewer and subject.

Jenna Gribbon and the magic trick of projected images

AM: I’m interested in the theme of doubling (projected images) as it manifests through mirrors, shadows, candles as dual sources of light, and subjects facing one another. What function does doubling or replication play in these latest works?

Jenna Gribbon: Using all of these mediating tools together creates the potential for magic, confusion, and revelation. To me, it accurately describes the process of seeing and reseeing, knowing and unknowing our loved ones, which is a central focus of my work. Mirrors, shadows, and projections operate both in metaphorical ways that we understand through psychology and as visual tools that simultaneously aid and complicate ways of seeing.

For example, a mirror provides a perspective we can’t achieve from our vantage point, but it can also fracture, obscure, or confuse what we would see if we were looking at it directly. Lights, mirrors, projectors, and shadows reveal and define in a way that can feel like magic—but sometimes, just like in a magic trick, when you think you’re really seeing someone, it’s actually a reflection or projection or shadow double.

The true reality of another person is elusive: Jenna Gribbon

AM: I was wondering how painting might be a way of knowing. I often think of translation as the most accurate way to know and, therefore, read a text. Do you think of painting as the ultimate way to really see someone? What does it mean, for you, to truly see?

Jenna Gribbon: Painting is a way of giving attention to a subject, idea, thought, or moment. It is a way of inviting others to share in your sensory experience of being while immersed in that feeling of attention. Like a mirror or camera lens, paint is another layer of mediation. It’s a layer that exists between the viewer and reality, but the obfuscation of reality is in service to another kind of knowing that is otherwise unknowable and, certainly, unshareable.

The multiplicity of selfhood, according to Jenna Gribbon

AM: I’m interested in selfhood as explored in these paintings. They seem to suggest that selfhood doesn’t emerge from singularity but rather from multiplicity and relationships—between subjects, as well as between subjects and the observing eye. Can you tell us about the self in your work: is it a collective self? How is it constructed?

Jenna Gribbon: It is difficult to describe visually the way we come to understand ourselves. We can only see ourselves through reflection or some other form of mediation, like photography. Recently, I’ve only appeared in my paintings through the parts of myself I can see—arms, legs, hands, and feet—or in a clearly delineated mirror. In this show, that’s mostly still true.

Yet there is one painting where I’m directly facing the viewer holding a light. I haven’t made a self-portrait this straightforward in many years. Maybe twenty years? However, in reality, this painting was made possible through the use of both a mirror and a camera. It’s not really me as I understand myself from the inside, but it’s rather a depiction of me that might be seen by my wife and child as I author these images.

It’s a reflected photographed-me with a discerning expression in the midst of my looking while illuminating.

The “unguarded humanity” of intimacy in domestic spaces

AM: The bodies in these paintings appear to be relaxed, conveying a sense of safety and a feeling of intimacy to the viewer. What’s the role of intimacy, both physical and emotional, in your work?

Jenna Gribbon: Portrayals of intimacy are a gift because they are a window that can only be opened from the inside out. Only I have knowledge of what my family looks like at their most comfortable, or most vulnerable, and there’s such a preciousness to those states—such beauty to unguarded humanity. If there’s a feeling I want to evoke in my paintings more than anything else, it’s empathy. I love the experience of seeing a stranger in a painting and thinking, “God, I just love her.” An intimate depiction of a subject creates the possibility for that experience—because we are so charmed by people who are being their most authentic selves.

Instead, physical intimacy is in my paintings for a slightly different reason. There is still such a dearth of images of romantic love between two women. Many (most?) people don’t understand what sex between women is, and might not even believe that it’s legitimate. I also think it’s important to show that women can be both sexual beings and mothers, and that both realities exist simultaneously in our bodies and our homes.

AM: I’m also drawn to the way these paintings might express the domestic beyond the relational subjects. Can you speak about your choice of props and objects—how do they contribute to creating the domestic space?

Jenna Gribbon: I wanted to give a window into the particularity of my home space. Objects, like people, hold energy and narrative backgrounds. They interact with light and shadow in complex ways that contribute so much to the feeling in a space. I included details of my environment as a way of communicating the feeling I have here. It’s a feeling I deeply love.

AM: Can you tell us about your decision to include written language and particularly the word, “cherry picker”?

Jenna Gribbon: That’s actually a Kim Gordon print that hangs in my living room. I liked including it for the confusion it contributes. It’s a painting that’s really embracing visual chaos.

Art as a refuge, art as a denunciation

AM: There’s a soothing sense of refuge emerging from these works—the flowers, the striped nightgown, the depiction of the pet. Can you tell us about the idea of refuge in these latest works?

Jenna Gribbon: We are living in such dark times. I have definitely been focused on my home life as a way to manage distress. The paintings are meant to show that we are not immune to the darkness, there is a lot of darkness and shadow in the paintings, but within the bounds of home, things are still very beautiful. The colors and shapes of the shadows are very beautiful. It’s a show about finding refuge in the people you’re close to and living vividly in dark times.

AM: I’m interested in how these latest works speak to the current political climate. Is any work of art inevitably part of a broader lineage of cultural and political dialogue, in conversation with the social climate of their time?

Jenna Gribbon: My works are overtly political. Knowing the current stance of the Italian government on marriage and family for the LGBTQ+ community, I really wanted to depict the beauty of the domestic life of a family helmed by a same-sex couple.

The gaze dynamic between viewer and subject: Jenna Gribbon

AM: Finally, I’m interested in how the subjects return or avoid the viewer’s gaze. What do they invite or ask of us as viewers?

Jenna Gribbon: To me, these paintings have a theatrical quality to them. The home is our stage and the viewer is seeing these tableaus unfold. The viewer is immersed in the scene until eye contact is periodically made, in a kind of breaking of the fourth wall, and the viewer is reminded of their position in relation to the subject.

Jenna Gribbon

Jenna Gribbon was born in Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1978, and currently lives and works in Brooklyn, New York, US. Her figurative paintings often depict her family—her wife and son—in loving, everyday scenes. Gribbon’s work is included in the collections of the Brooklyn Museum in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Museum of Modern, and Contemporary Art (MAMCO) in Geneva, and Collezione Maramotti in Italy, among others. Rainbows in Shadows is her first solo exhibition in Milan. It opens on June 5th at MASSIMODECARLO Milano and runs through July 25th.

Anna Montagner