How Richert Beil shapes garments from grit

From latex tailoring to deadstock suiting, Richert Beil’s work sits in the friction between instinct and resistance—imperfection, limitation and delay are part of the process

Interview with Jale Richert and Michele Beil – Richert Beil thrives in raw, unfinished spaces that echo their brand’s gritty honesty

Jale Richert: We’re in a raw moment. Everything feels unresolved, mid-transition, unfinished. We’re renovating our new studio space, which was originally meant to be ready by early September. Now we’re looking at October or November. That’s how construction goes—every time you open up a wall, you find something unexpected, you have to deal with. Design feels similar. You start from a certain idea, and the moment you begin breaking it down, other layers reveal themselves—challenges, accidents, shifts you didn’t plan for.

The space is a reflection of how we operate as a niche brand. We look for locations that connect with the collection. It’s part of an overall process. We’re not creating commercial collections that can be shown anywhere, with perfect lighting and polished minimalism. We gravitate toward spaces that feel lived-in, with odd angles, flaws, or a bit of tension. It could be a gallery, or a space with an intellectual residue, or just something raw. It has to echo the intention of the collection. We see our work as conceptual, sometimes artistic. The location has to hold that.

Michele Beil: We’re drawn to rawness, but it has to be real. There’s a difference between a space that is genuinely under construction and one that has been curated to appear gritty or industrial. Like those all-black collections that are styled to seem deep or edgy—they rarely get the tone right. We prefer spaces that are in honest transition—unfinished, flawed, not pretending. That’s where it feels alive.

Jale Richert: Roughness is the starting point of everything. Even now, as we’re reshaping parts of the brand—cleaning, letting go, refining—we’re noticing that some of the things we built at the beginning still hold. They were formed intuitively and have lasted. The renovation of our studio feels symbolic in that way. Rawness is where it begins—space, idea, silhouette. That first form, the unfiltered one, is what carries the charge.

From studio to city: Berlin isn’t treated as a muse, but as a functional backdrop—useful, accessible and coincidentally home. Richert Beil could exist anywhere, but for now, it unfolds here

Jale Richert: I came from a smaller town, but I’ve lived in Berlin since 2009. I would almost call myself a Berliner—I’ve lived here as long as where I grew up. In a way, it is my hometown. Berlin is honest and unfiltered. It’s also a deeply political city. People express themselves with conviction, and that creates a sense of freedom.

Michele Beil: I’m originally from Hamburg—a city where people are proud to stay. Berlin didn’t immediately feel like home. It took time. Over the years, it’s become the natural ground for us. Berlin is where the label took form years ago. Not because the city inspired us with its atmosphere or visuals, but because it became part of our ecosystem. It’s a practical part of our process. Berlin is the people we work with. The woman who sells us a specific kind of yarn. The Turkish supplier with a certain zipper that’s impossible to find elsewhere. Even down to sourcing—buttons, cat brakes, trimmings—it all happens here.

Jale Richert: I wouldn’t say the brand is bound to Berlin. Richert Beil is shaped more by the stories we tell than the streets we walk. If we were to move to the countryside tomorrow, the work would adapt, but the core would stay intact.

Material honesty, for Richert and Beil, rejects clean-cut rules. It’s a raw, instinct-led process—messy, intuitive, and present in every cut, choice and seam

Jale Richert: Material choices begin with the hand—weight, texture, resistance, how it drapes, how it shifts on the body. We imagine how it moves through daily life. We start with familiar silhouettes—something as simple as a classic T-shirt—and from there, we elevate it through material. We both tend to wear very basic pieces, so the interest has to come from the substance, not the shape. That’s where the play begins.

Latex, for instance, is deeply conceptual—it’s the creativity behind it. We treat it like a traditional fabric, tailoring it, but the rules are different. You don’t sew it. You glue it. That completely transforms the construction process. There’s a freedom in that. Latex isn’t precious in a conventional sense, but it demands care. It’s tactile, unruly, alive.

Michele Beil: Here’s the contradiction: latex is natural—it can be considered sustainable. At the same time, it’s fragile. It has a lifespan. It changes with wear. It reacts to sweat, to skin, to metal. It stains, discolors, stretches. It tells a story as it ages. The material absorbs experience. Over the years, we’ve continued to explore it more deeply. It’s become part of our signature, paired with sharp tailoring and exacting cuts. That contrast is Richert Beil.

Jale Richert: We manipulate everything by hand. One technique we return to is cotton coated in silicone. We make it ourselves, sheet by sheet, in the studio. Then we cut and construct the garments from there. It’s not a process that can be outsourced. The tension between synthetic treatment and handcraft is where the integrity lies. For us, it’s about what the material does, how it behaves, how it resists or surprises.

Michele Beil: With leather, the responsibility is higher. We work with a verified supplier who handles the ethical sourcing on a smaller scale. It’s a local supplier that works with theaters and independent makers. We source leftover or small-batch pieces. There’s no need for large orders because our collections are intentionally limited.

Jale Richert: Using leather—one that’s ethically sourced—is the promise of longevity and durability. It’s a material with memory, with time embedded in it. This matters to us. We don’t work with mass production. Everything is handmade, in small numbers, right here in Berlin.

There was a time when we recycled old motorcycle gear. We also learned that recycling isn’t always the most energy-conscious route. Sometimes, the cleaning process is so demanding, chemically and mechanically, that it defeats the purpose. We always ask: does that make sense? If yes, we do it. If a new leather piece makes more sense in that moment, we go for that with intention and durability in mind.

We’re aware that fashion, at its core, isn’t sustainable. If it were, we’d all just wear vintage. There’s space to make conscious decisions—to design with thought, to produce with restraint.

Michele Beil: That’s our version of sustainability: slowness, refinement. We don’t chase seasons. We build collections over time. We produce in small volumes, with care.

Alternative materials are possible, but rarely practical—more expensive, less enduring. An interview with Richert Beil

Jale Richert: We’ve experimented with alternative materials. Some looked promising, at least in theory. The reality is that they didn’t hold up. The quality wasn’t there. They cracked, they tore, they didn’t wear well. You touch them, move in them, and the illusion falls apart. There’s often a nice story behind them, but not much structural integrity.

There’s also a transparency issue. Where do these materials come from? You get a poetic narrative story, but the production happens far away, and the process is murky. One time, we used one—it looked good—but then it degraded so quickly we couldn’t stand behind it.

There may be better versions on the market, but they tend to be even more expensive than real leather. And they still lack the longevity, the feeling, the weight. Most people aren’t ready to pay premium prices for something experimental, especially when the quality isn’t guaranteed. In the end, you’re compromising twice: performance and perception.

Michele Beil: Think of fake leather trousers. If there’s no fabric backing and you move too much, they rip at the seam. They don’t last. That doesn’t happen with leather. Leather is elastic in a way—it breathes, it flexes, it ages with grace. These synthetic substitutes just don’t live the same way. At least, not the ones we’ve tested.

That’s why our approach to sustainability has shifted toward tailoring. Lately, we’ve been working more with deadstock suit fabrics from a small supplier in Italy. They do their own finishing processes, their own treatments. These wool blends, these refined cloths—they’re rare, textural, considered. That’s where we’ve found meaning—more than in chasing the next ‘eco’ leather.

Plastic invites experimentation but rarely stands up to the demands of wear, function, or time.

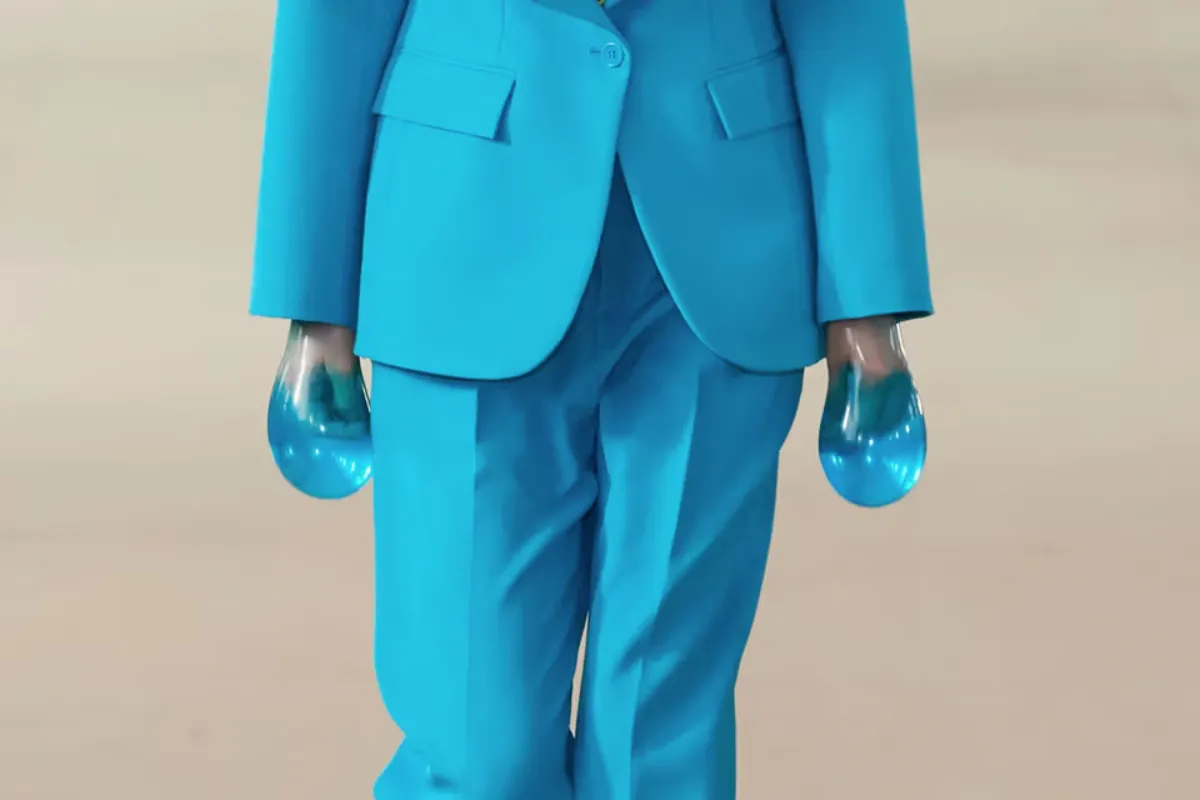

Jale Richert: There’s a distinction between what we present on the runway and what we offer in the stores. On the runway, we can be bold, with sculptural, upcycled pieces, garments that function more like art objects. They carry the concept and the narrative. Translating it to daily wear? That’s another story. Comfort, durability, price—these things change the equation.

Michele Beil: It’s something we’ve encountered with other materials too, especially latex. There is a niche audience that wears it with intention, even regularly, but that’s rare. We worked on the flower coat for three months, handcrafting each rose petal one by one. Of course, we’d sell it or loan it for an event, but it’s not something twenty people walk in and ask for. It’s more about offering a glimpse into our world. Communicating the storyline, the hours of labor, the discipline behind a collection, even if a piece only exists once.

With plastic, the thinking is similar. We ask: how does this material function? What’s its role in the collection? Is it a concept carrier, or something to live in? The answer defines the outcome. If it can’t meet the demands of time or body, it stays in the realm of the idea.

For Beil and Richert, exotic skins and fur remain non-negotiable—material choices that cross an ethical line, no matter how you frame them.

Jale Richert: Exotic animals. That’s our threshold—no exotic skins, no fur. We’ve never been interested in it, even from a conceptual standpoint. There’s no sustainable or ethical way to justify it. You could recycle vintage pieces, but then it still plays into the same narrative. It continues the story we don’t want to tell. If something new comes onto the market, something that authentically mimics the tactile or visual qualities of exotic skins, we’d be curious. We’re open to innovation. That’s part of the work.

Michele Beil: It’s never appealed to us aesthetically. We gravitate toward unembellished materials—plain fabrics with clarity and presence. We don’t need overt textures or animal-based surfaces to tell our story. In that sense, there’s no sacrifice. This line we’ve drawn—ethically, materially—is fully aligned with who we are and what we want to create.

There are places for experimentation, but black is not one of them. It is Richert Beil’s constant—uncompromised, elemental and deliberately stark.

Michele Beil: Black is the essence of Richert Beil. It holds everything together.

Jale Richert: It’s both presence and restraint. Black gives a sense of security with a touch of drama. It brings presence, but it also silences everything around it. People think it’s the easy choice, the safe one, but it’s not. Mixing different tones of black is a huge no for us. No black is ever the same. Black comes in different undertones—blue, red, brown—and they clash in ways you only notice once it’s too late. Suddenly, what was meant to be a black collection becomes unintentionally colorful. If you make a jacket and the sleeves are slightly off-black, it’s ruined.

We pay close attention to details. We play with different textures and finishes, but the undertone has to match. I feel exposed in light colors, but black—it gives a sense of control, seriousness.

Michele Beil: Black is intellectual. It reflects our world, the people we surround ourselves with—artists, designers, creatives. It’s quiet but still expressive.

Jale Richert: We almost entirely dress in black. Could I sleep in it? No. That would feel wrong.

Interview: Richert Beil emerged not as a calculated decision, but as an inevitability. For Richert and Beil, the label was a natural evolution that simply made sense.

Jale Richert: Meeting Michele was the turning point for both of us. I grew up in a small town, in a family that was not involved in art and design. Everything was more practical. My mother is a teacher; my father became a reverend later in life. Everyone in my family works in social services. Fashion is not significant in that world, but I was always drawn to it—to sewing, to the craft. My parents supported that fully. Then I met Michele, and it just clicked. I experienced different materials, different perspectives. I always loved his style and approach.

Michele Beil: I got to know designers like Yohji Yamamoto and Comme des Garçons when I was eight. My mother is an artist, so aesthetics, visual expression, it was all there from the start. She’s not walking around in big designer logos, but she has a sharp eye and her own individual style. I was immersed in that early on. Still, I’m now learning from Jale.

Jale Richert: You’re learning how to survive with me [laughs]. Yes, we come from different backgrounds, and that’s helped us shape our brand—the openness to different opinions, different lifestyles, different ways of seeing things. Over time, we’ve found our own small bubble, built through a mutual intuition. It shapes how we work, how we build collections. There’s part of our personal story inside every collection.

I was interested in fashion, but I could never find what I was looking for in stores. We started building it ourselves, based on our taste and vision. First, there was a pull towards unisex design. But we didn’t want to rely on oversize or shapeless forms. Tailoring was direction we went for. We design gender-neutral clothing that fits a range of body types without having to alter it. That’s the big work behind what we do.

In casting, Richert Beil looks for people who feel real, people they’d want to talk to, not just dress. Looks are secondary

Michele Beil: Backstage is always calm. No tension, no ego. It’s warm, focused. That’s intentional.

Jale Richert: Casting is a big part of what we do. We must like the people we work with. We must like their character, who they are. We don’t just send out a brief and choose based on looks. We talk to them. We get to know their story and see if it resonates with Richert Beil.

Feeling alone isn’t enough to sustain the next chapter. Now, the focus is structure—building the internal architecture the brand needs.

Jale Richert: There’s always room for growth. Right now, structure is what we’re working on. The internal structure—our systems, our pace, the daily process. With the studio still being built, there are delays. Things slip through the cracks. It’s not as tight as we want it to be.

Michele Beil: The brand started with instinct. To sustain it, we need to know exactly where things go—who’s doing what, and how every part functions. That’s what we’re working on now. The groundwork. If it’s solid, everything else follows. Hopefully, in a while, it’ll run the way it should.

Susanna Galstyan