We all want more sex! Independent publishing and emerging fashion

From Butt Magazine to Carne Bollente and Ludovic de Saint Sernin, independent publishing and niche fashion labels transform sex from spectacle into intimacy – shifting from glossy provocation to everyday openness

Sex, fashion, publishing: rewriting desire

That vocabulary is no longer sufficient. Independent magazines and small fashion brands have rewritten intimacy. Instead of provocation, they offer disarming frankness; instead of perfection, they foreground fragility. Sex today is not an external spectacle but an everyday practice, woven into publishing and clothing as a language of identity and recognition.

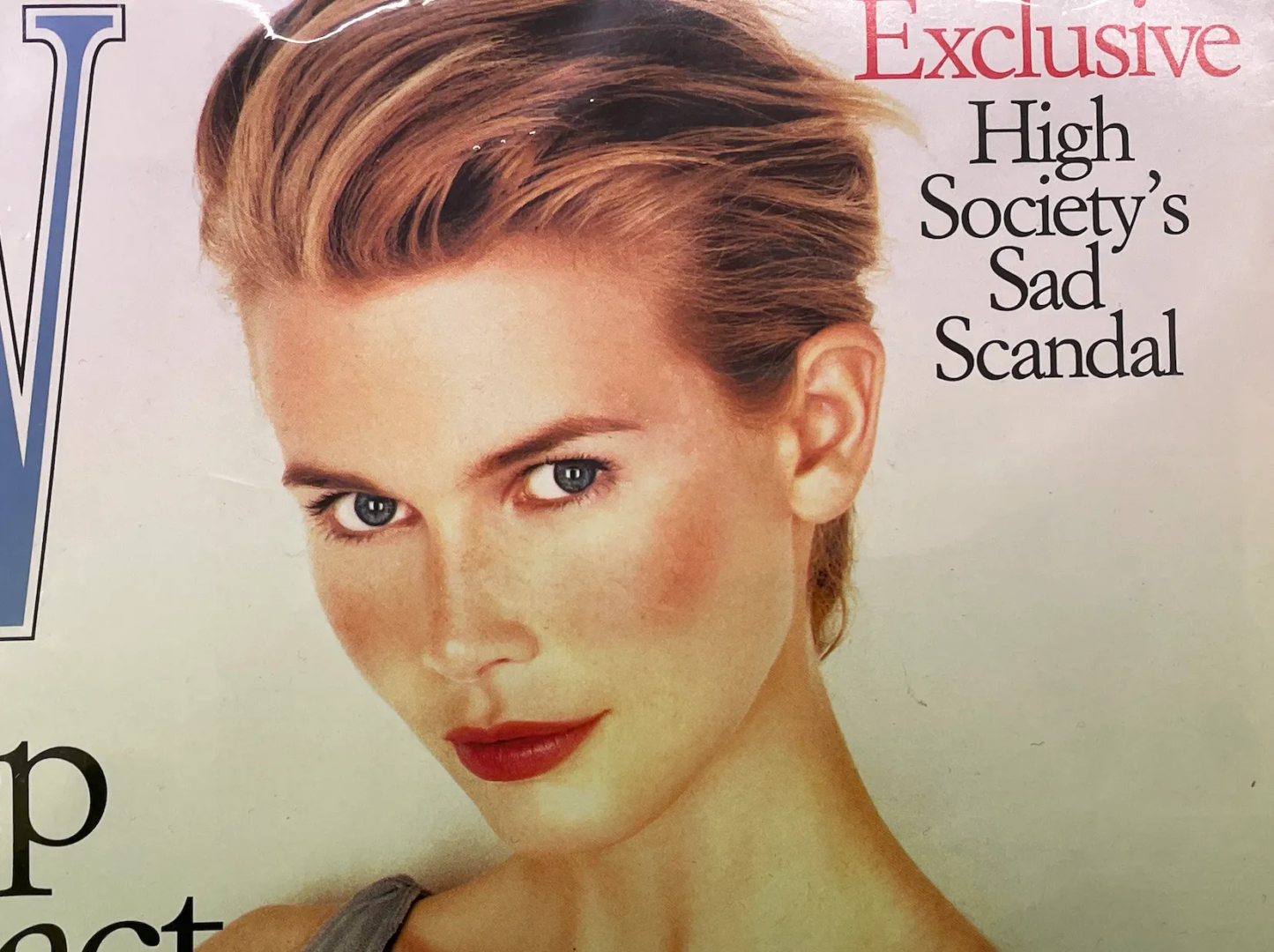

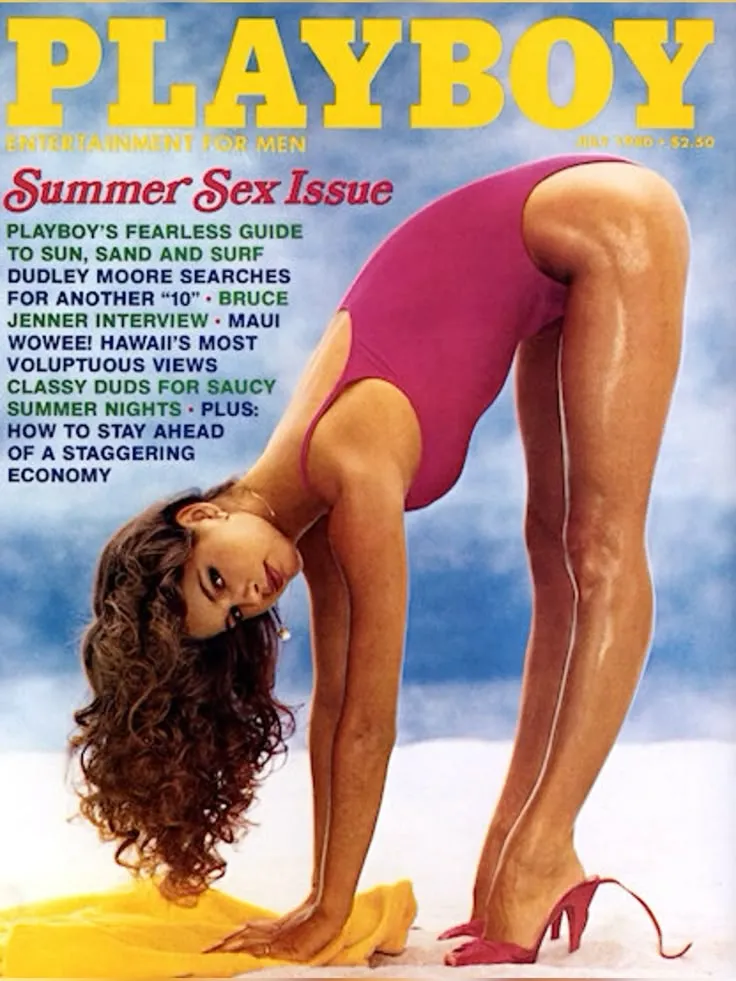

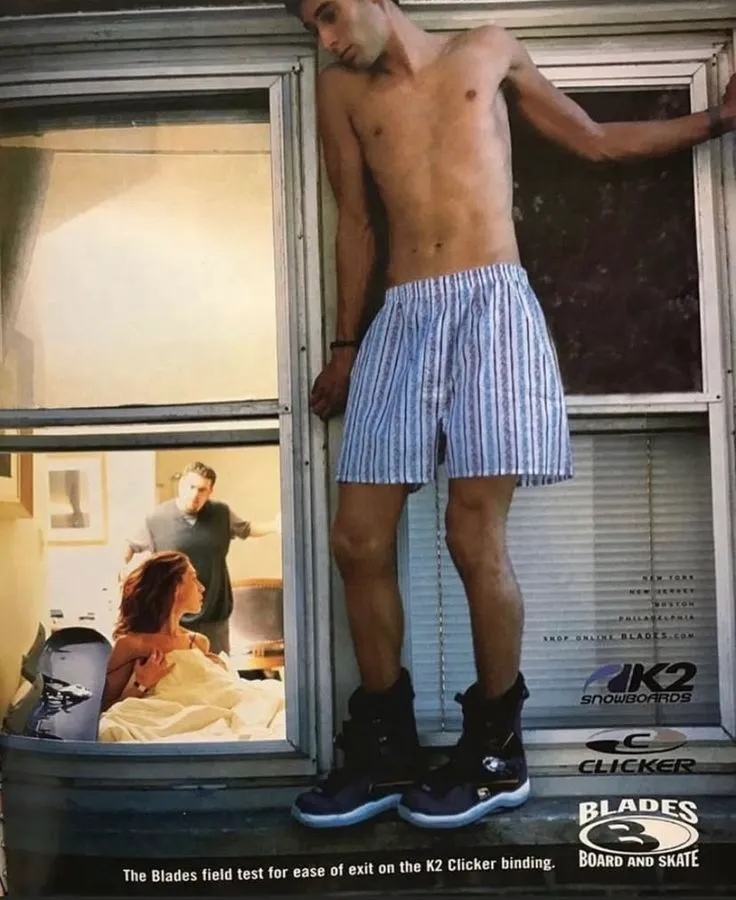

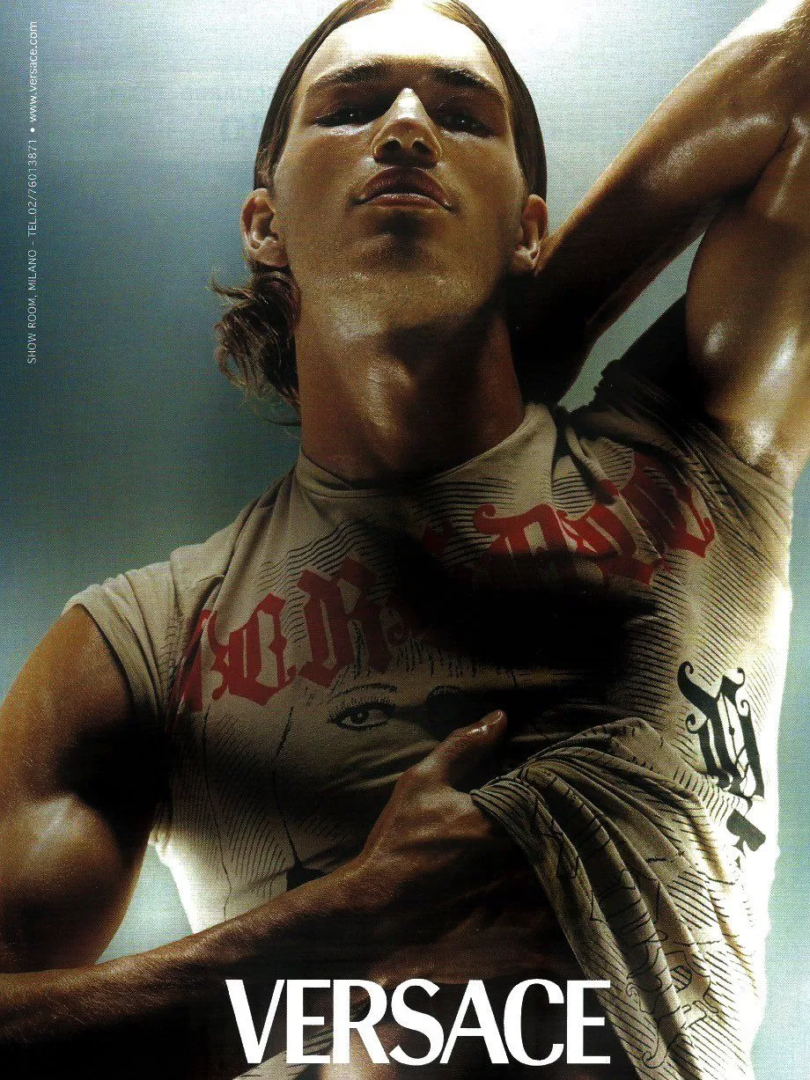

In the 1990s, magazines and advertising agencies presented sex as a product of shock and aspiration. Tom Ford’s Gucci campaigns epitomized this: bodies oiled, fragmented, staged as erotic weapons. Eroticism was consumed as a luxury accessory — remote, intimidating, unattainable.

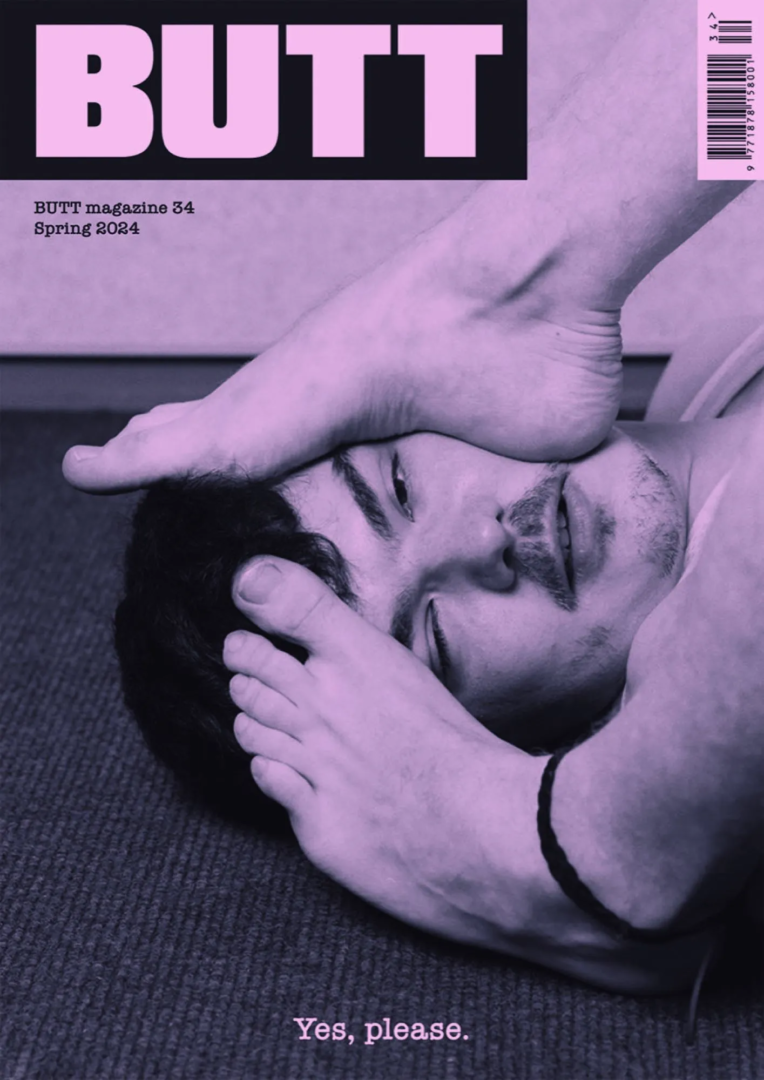

Butt Magazine and the indie press of desire

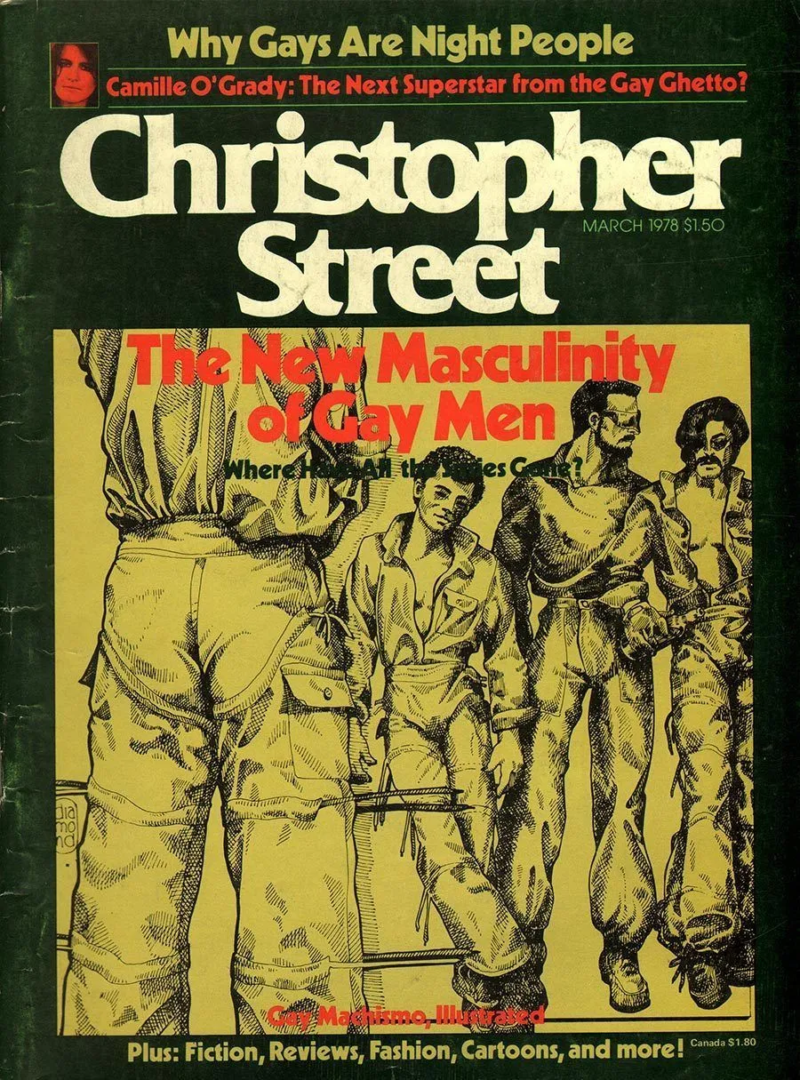

When Butt Magazine launched in 2001 in Amsterdam, it broke with glossy gay media. Its pages — pink paper, cheap print, staple binding — featured ordinary men, photographed candidly, interviewed without censorship. There were no six-packs, no airbrushed fantasies. Sex was presented as lived experience, as conversation between equals.

This shift was not only aesthetic but political. Butt turned publishing into a site of intimacy: the magazine itself became a place where desire could be articulated without shame. Readers found themselves reflected not in perfected icons, but in peers. That intimacy — small, fragile, printed — created a community.

The legacy of Butt continues. Phile: A Journal of Desire and Disgust explores sex through critical writing and visual culture, presenting it as both artistic and political terrain. Little Joe, devoted to queer cinema, reconstructs the history of desire in moving images. Even Odiseo, a Spanish magazine combining erotic photography with essays, insists that sex belongs not to the margins but to the intellectual center of cultural discourse. Each title demonstrates that publishing is not just distribution of content, but circulation of bodies, ideas, and possibilities.

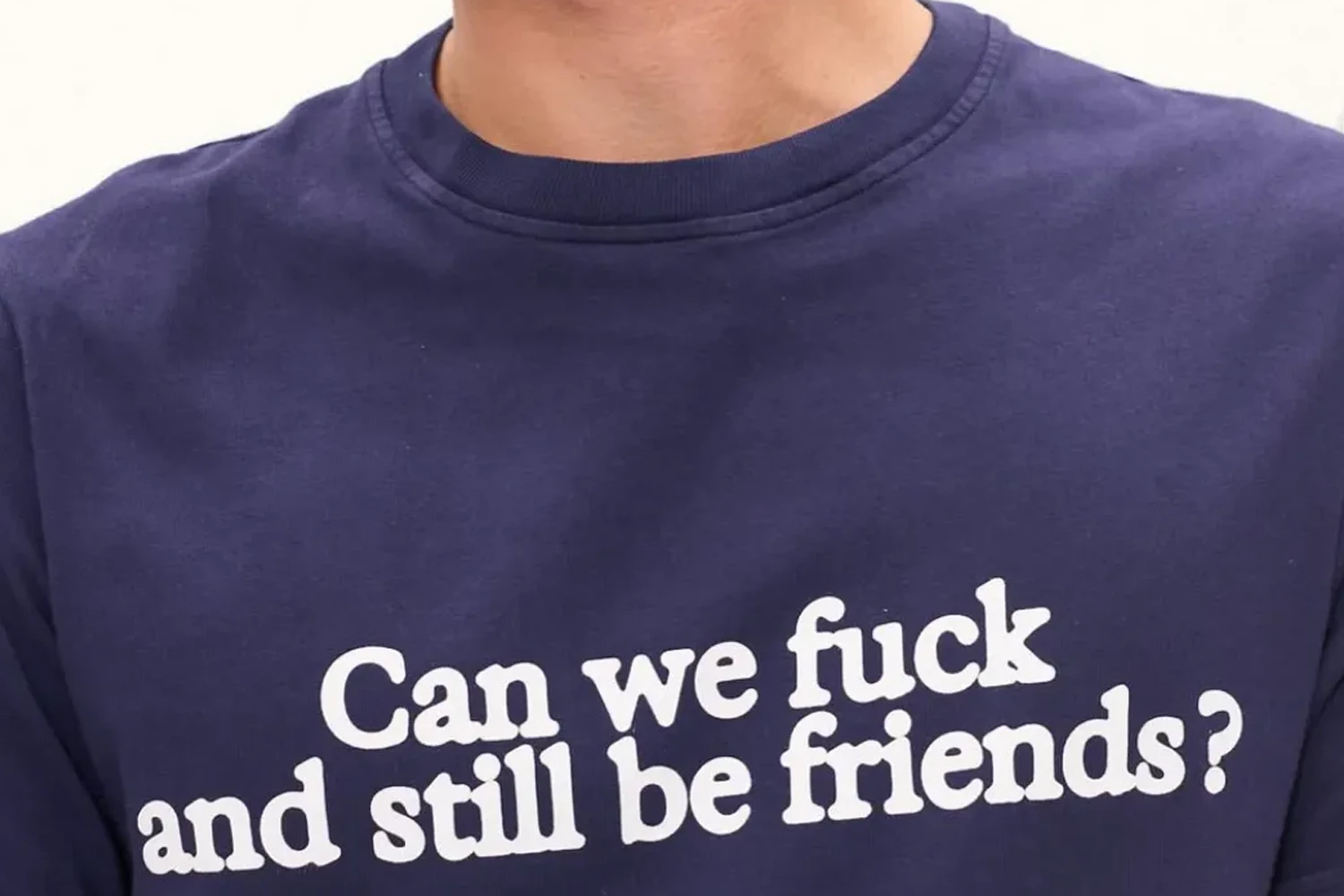

Carne Bollente: eroticism embroidered

Paris-based label Carne Bollente translates erotic freedom into everyday dress. T-shirts, sweaters, and caps carry embroidered scenes of threesomes, masturbation, and playful intimacy. Worn in public, these garments normalize sex as part of social life: not scandal, not provocation, but openness.

By stitching eroticism onto cotton, Carne Bollente removes sex from pornography and installs it into the banal fabric of the street. Wearing one of their pieces means declaring sexuality not as transgression but as part of one’s identity — not hidden but integrated.

Other small brands follow similar paths. Awkward, Berlin-based, prints zines and garments dealing with queer eroticism; Boychild uses performance and clothing to reframe gender and desire. Each case shows how independent fashion is less about trend and more about publishing through textiles: the garment becomes a page, the body becomes the distribution channel.

Ludovic de Saint Sernin and the aesthetics of vulnerability

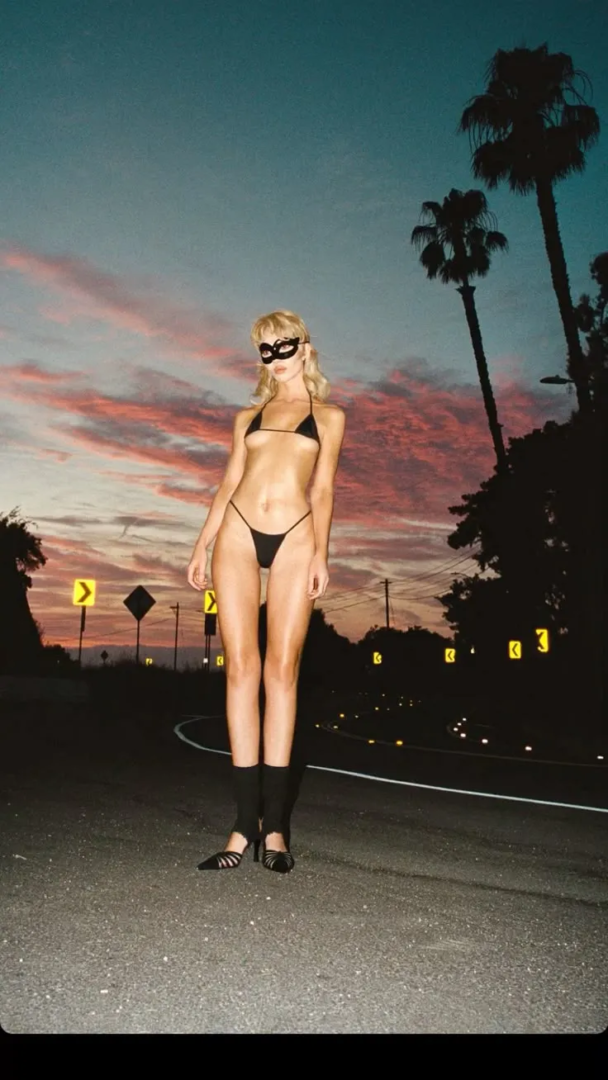

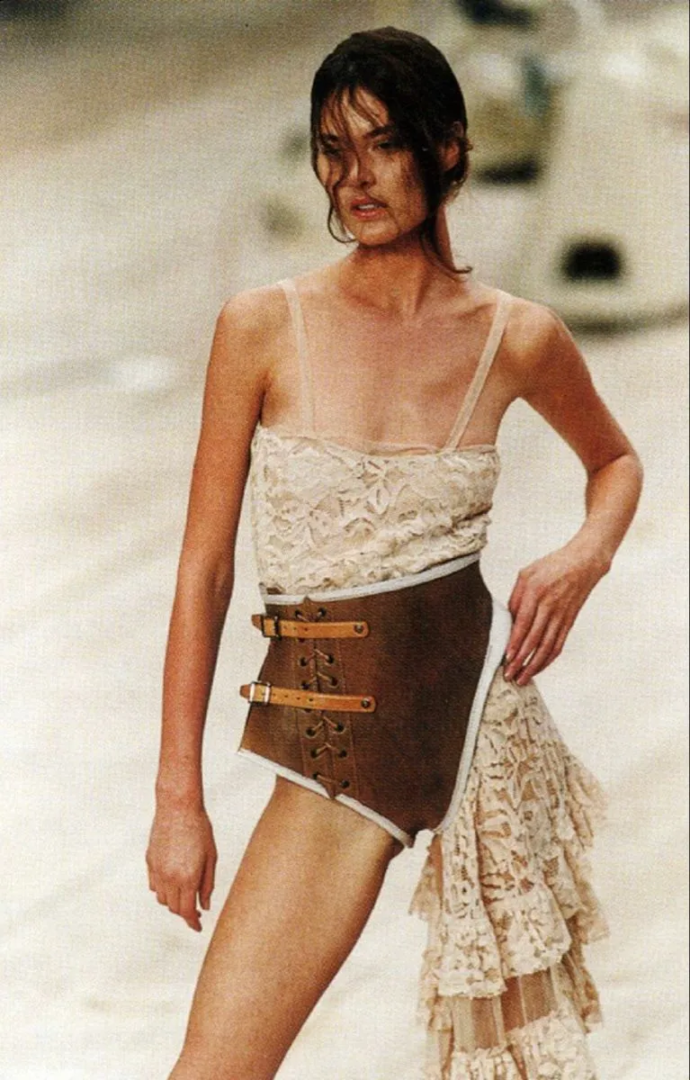

French designer Ludovic de Saint Sernin pushes fetish codes into the fashion system but empties them of aggression. Leather straps, metal rings, lace-up details, and transparent fabrics echo BDSM aesthetics, but his clothes frame fragility rather than domination.

Models walk in lace briefs, sheer tank tops, satin shorts. Instead of conquest, the effect is exposure. Bodies are presented as porous, receptive, vulnerable. The collection transforms symbols of control into tools of softness. In this sense, de Saint Sernin belongs to a new generation of designers who use erotic codes not to affirm power but to question it — a reversal of the patriarchal script of desire.

The resonance is wider. His work connects to photographers like Wolfgang Tillmans, who has long portrayed queer intimacy without spectacle, and to the visual legacies of clubbing, where fetish gear has been worn less as armor and more as communication.

Queer nightlife as laboratory of aesthetics

Much of this convergence between sex, fashion, and publishing originates in nightlife. Clubs have always been laboratories of desire, spaces where dress codes and erotic codes intertwine. From New York’s underground in the 1980s to Berlin’s Berghain today, nightlife has produced aesthetics that migrate into both fashion and editorial projects.

The logic is collective: dance floors turn vulnerability into visibility, bodies into texts. What happens in clubs — leather harnesses, sheer fabrics, gender play — travels into fashion shows and magazine spreads. Publishing then documents, amplifies, and transforms these experiments into cultural memory. Without queer nightlife, neither Butt nor de Saint Sernin would exist in the same form.

Independent publishing and sexual openness

Independent magazines extend this consideration. They approach sex not as commodity but as cultural question. Kinkdocuments BDSM cultures through interviews and photo essays. No Place Like Home explores domestic intimacy, mixing erotic imagery with reflections on belonging. Each project expands the range of how sex can be represented: tender, ironic, messy, intellectual.

By printing what mainstream media censors or sensationalizes, indie publishing normalizes sexuality as conversation. It dissolves prudery without replacing it with spectacle. In doing so, it makes sex a terrain for thinking — not only about bodies, but about politics, aesthetics, and futures.

From glossy eroticism to playful intimacy

The common thread across these practices is a rejection of spectacle. In the 1990s, sex was presented as something to buy into, a tool of seduction attached to luxury. Today, small brands and magazines use it to connect, to dismantle shame, to propose vulnerability as a new mode of masculinity and femininity.

Sex, fashion, and publishing intersect because all three produce narratives. In this convergence, sex is not extraordinary but ordinary — embroidered on a hoodie, printed on pink paper, staged on a dance floor. Desire becomes visible without provocation; intimacy becomes shareable without scandal.

We are no longer in Tom Ford’s era of glossy provocation. Instead, independent voices insist that sexuality belongs to everyday culture, that intimacy deserves publication. Pleasure, once locked into spectacle, is now written into community.

Digital intimacies: censorship, platforms, and virtual desire

The digital sphere has expanded the terrain of erotic visibility while imposing new forms of control. Social platforms like Instagram perform a paradox: they monetize desire but censor the body. Queer, trans, or fat expressions of sexuality are often removed under the guise of “community guidelines,” while luxury brands can circulate hypersexualized imagery without consequence. What once was moral censorship has become algorithmic governance — a politics of visibility written in code.

If independent magazines made sex printable, platforms like OnlyFans have made it transactional. Here, self-publishing becomes self-monetizing: the body as both medium and income. Many queer and feminist creators have turned this space into an arena of autonomy, reclaiming sexual labor as self-expression. Yet this freedom remains unstable — dependent on metrics, shadow bans, and precarious attention economies. Desire, under platform capitalism, survives only as long as it performs.

Meanwhile, digital fashion and virtual avatars propose new erotic frontiers. Designers create immaterial garments, worn by bodies that exist only as data, where gender can be multiplied and flesh becomes interface. In this post-physical intimacy, clothes no longer touch the skin but the screen. The fantasy of liberation coexists with the infrastructure of control: even in virtual space, the politics of who may be seen — and how — remains.

The digital has not erased erotic publishing or fashion; it has reprogrammed them. What once circulated as paper and fabric now travels as pixels and code, but the question endures: who controls the image of desire, and who gets to speak it?

Politics of desire: intimacy under conservatism

The resurgence of conservative politics in the 2010s and 2020s — from Trump’s America to Europe’s far-right revival — has turned sexuality once again into a battlefield. Moral panic, nostalgia for “family values,” and the policing of gender expression have re-entered the mainstream. Under these regimes, desire becomes suspect; visibility itself becomes a threat.

Fashion and publishing respond by reclaiming eroticism as resistance. Independent designers, queer editors, and artists use tenderness, pleasure, and transparency as political weapons. In a world that seeks to reimpose shame, showing one’s body becomes an act of defiance. A sheer tank top, a pink zine, or an intimate photograph are not just aesthetic gestures — they are affirmations of existence against a culture of fear.

This is not the grand provocation of the 1990s but a quieter form of dissent. Instead of shock, there is insistence, instead of scandal, persistence. The new erotic culture answers authoritarian nostalgia with emotional honesty, and patriarchal power with collective vulnerability. Desire, once disciplined by the state and now surveilled by algorithms, returns as a small, fragile, public truth.

Ario Mezzolani