The Politics of Oil: Tanoa Sasraku Reframes Corporate Souvenirs as Violent Symbols

Working with found objects, sculptures, and UV-printed paper works, Tanoa Sasraku maps the destruction of the oil industry across global affairs and the environment

Rediscovering Corporate Trinkets from the Oil Industry

In the latter half of the twentieth century, petroleum companies across the globe created corporate trinkets celebrating what they saw as a benchmark in human progress — oil, a precious and massively destructive natural resource.

Companies like Derrick in the United States, BP in the UK, and the Gulf Oil Corporation in Zaire produced paperweights housing small amounts of crude oil, often accompanied by golden rigs, souvenir coins, and engravings marking new ventures. At the time, they were found on mantlepieces, in homes, and on the desks of oil tycoons. Now, they mostly surface on online marketplaces like eBay.

Morale Patch at the Institute of Contemporary Art

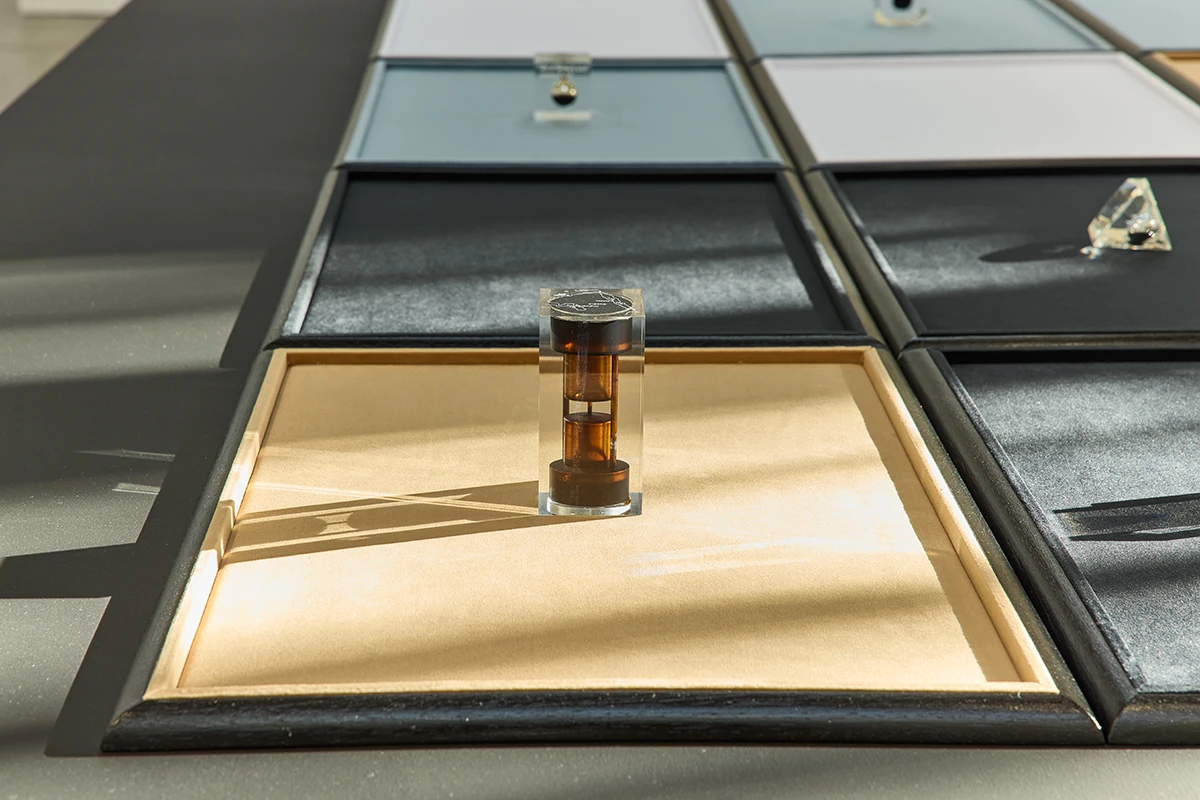

On show at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London, Tanoa Sasraku’s Morale Patch is a response to these tokens. Working across paper, sculpture, and found materials, the British artist interrogates what symbols of the oil industry mean in a world that can no longer ignore its impact. In ‘Watchlist’, she arranges 32 paperweights on a gridded landscape recalling both a chessboard and a wartime strategy map. A cluster of Middle Eastern trinkets and two American pieces stand in for the 1991 Gulf War. A Soviet memento evokes the invasion of Afghanistan.

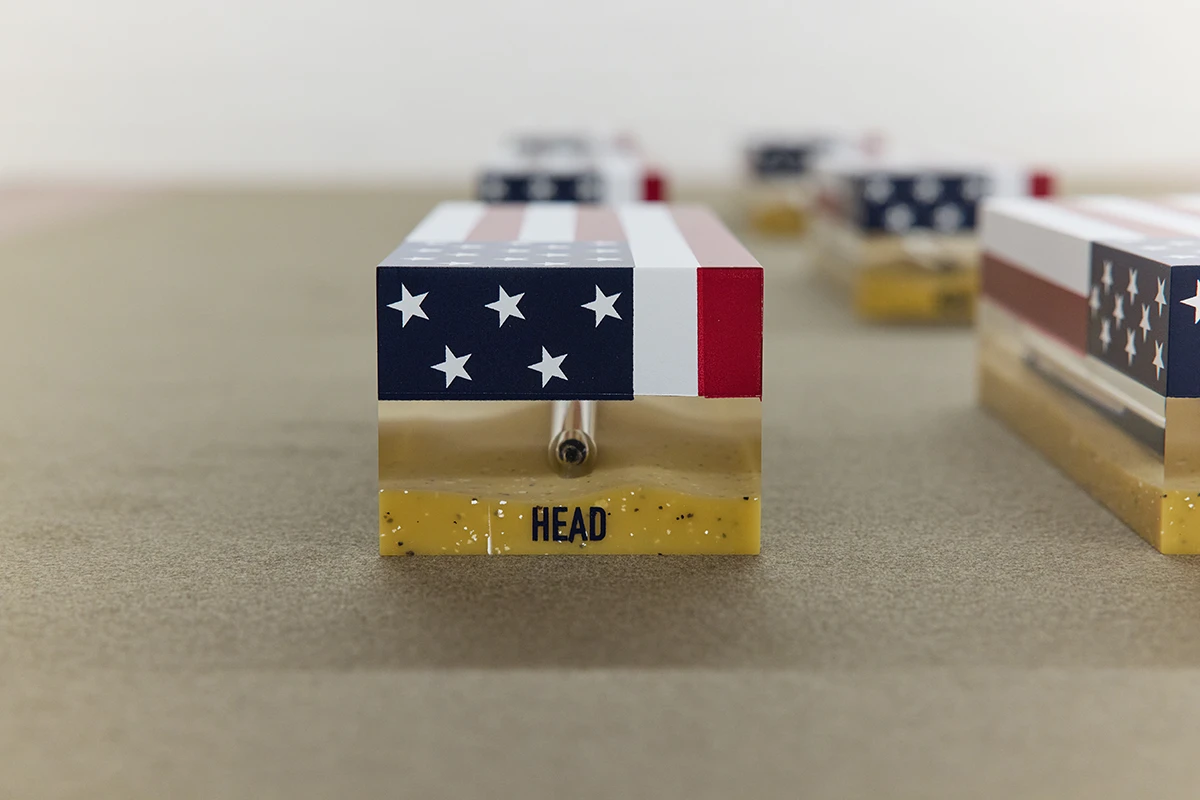

In ‘Shell (I)’ and ‘Shell (II)’, Sasraku crafts her own memorabilia: a series of acrylic, coffin-shaped paperweights adorned with American flags over broken pens and sandy terrains. On the walls are rippling paper works, onto which Sasraku has rendered scaled-up and distorted symbols like the Global War on Terrorism Medal. UV-printing means these pieces are designed to fade over time.

Taken as a whole, Morale Patch reframes corporate and military symbols to critique nationalism, environmental decay, and geopolitical power. In a world still captivated by the allure of oil, Sasraku demonstrates that the fetishization of resources has complex, ongoing consequences on politics, nature, and human life.

Interview with Tanoa Sasraku

Before the opening of Morale Patch, I spoke with Sasraku about the complex legacies of these paperweights, the state of the oil industry today, and how time and temporality overlap with her practice. Turning to the personal, we explore her frustrations with reductive labels, her relationship with her father, and spirituality.

Joshua Beutum (JB). There are some intriguing textures running through Morale Patch. What does ‘roughness’ mean to you?

Tanoa Sasraku (TS). Morale Patch relates more to smoothness and slickness than roughness. There are ripples in the paper works, but they feel more like draped fabric than textural coarseness. And the techniques underpinning the show are less physically abrasive than usual. My body is typically destroyed by the processes I employ — I work with so much stone and silt pigment that the skin on my fingers wears down.

JB. Would you say that the show is thematically abrasive?

TS. Yes. But I’ve tried to keep it open. Artists tend to create shows about how bad the oil industry is, which becomes a moralistic and didactic exercise. I’m more interested in how we worship oil. It’s driven us forward. It can be a life force, but it’s also a death matter. The abrasion is in that juxtaposition.

JB. Let’s touch on oil — it’s thick, slippery, sexy. What draws you to it?

TS. I use a lot of minerals, especially iron oxides. Since much of my work addresses death and mourning, I was looking for something that spoke to the body and its degradation. And crude oil is literally made of ancient bodies that have been pressurized underground for millennia. First, I tried painting oil onto paper, but I decided the paperweights were the best way to harness the resource.

Nature: Tanoa Sasraku’s use of natural materials

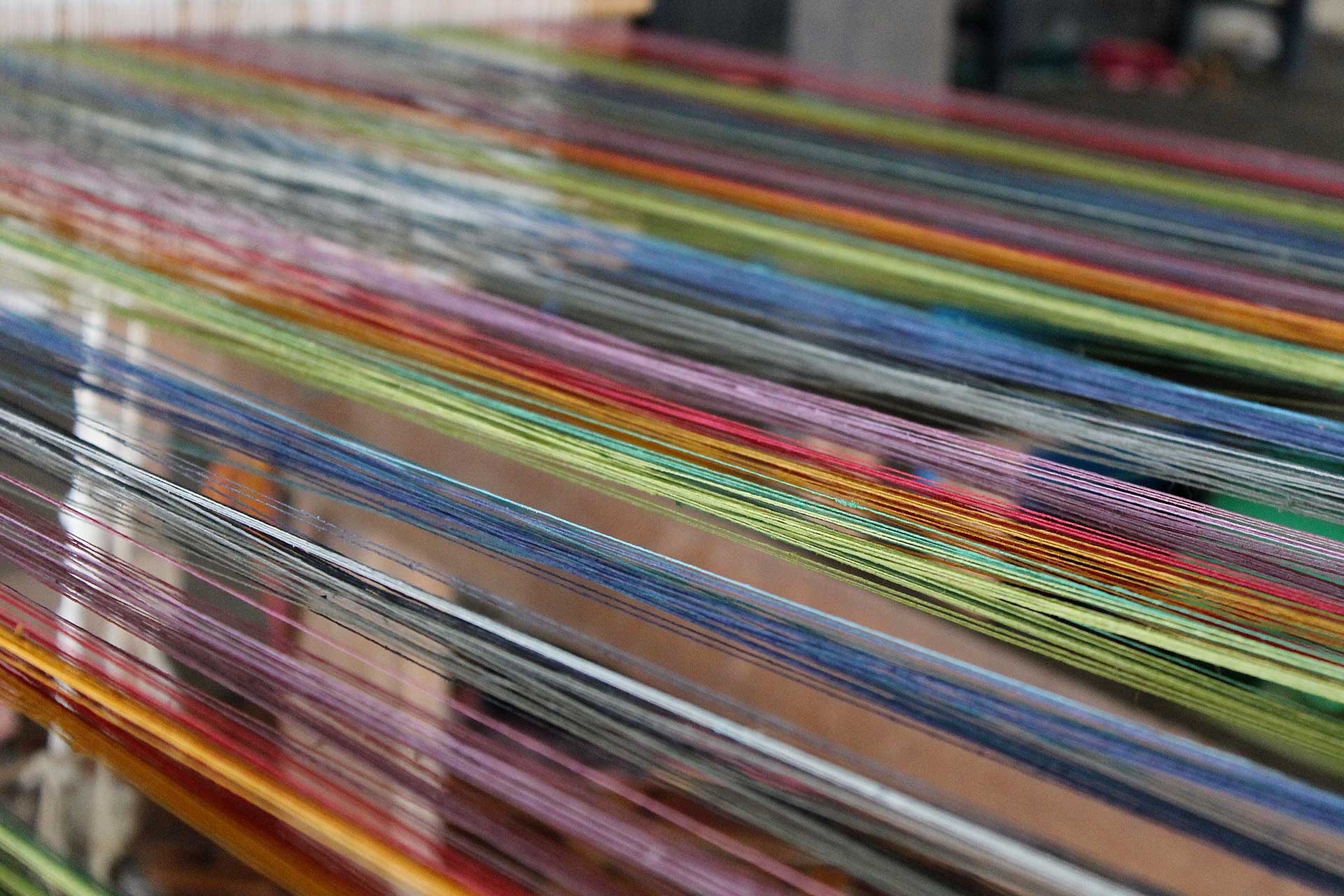

JB. This fixation on oil makes sense given your frequent use of natural materials and processes in your work. Consider Terratypes (2022), where you soaked textiles in rivers, oceans, and bogs. I wonder how you view nature in relation to your practice. Is it a collaborator, an inspiration, or a tool?

TS. Most of my early experiences occurred in the moors of Devon, where I grew up, and outdoors in Ghana, where my father was from. My work is often about revisiting that past. The color palette in Terratypes was defined by whatever the earth provided and however it chose to represent itself. In this sense, nature is a collaborator — not something to take from, but something to work with.

In the Studio with Tanoa Sasraku

JB. Walk me through a day in the studio.

TS. I normally start at eleven, which is just enough of a rebellion against the typical nine-to-five. For Morale Patch, I’d turn on the sunbed for my UV-printed works and let it process, while I’d search for the paperweights on eBay.

JB. With such a connection between your practice and nature, it’s surprising that you chose to use sunbeds rather than the sun for UV printing.

TS. The sunbeds are channeling an era of ambition, vanity, and failure. They’re from the late-1980s to 2000s — a Reaganite moment that’s become an obvious precursor to Trumpism and the attitudes we’re contending with today. Using the tools from that particular era infuses the work with the energy of that time.

JB. Let’s talk more about this temporal element. How do you view time?

TS. I often walk through painful memories, and that can be quite melancholic. But time is also a tool. It offers me things from the past — moments to revisit and relics for reinterpretation. The internet is a great place to find those objects.

Paperweights in Morale Patch

JB. What’s the most interesting paperweight in Morale Patch?

TS. There’s one that BP issued in November 1975 to celebrate the first oil found in the UK. It’s shaped like a Christmas tree: a glittery base, a brown-stained cone, and a BP shield where the angel should be. It’s camp. Since it’s made of plastic — which is a petroleum-based product — it will eventually turn back into oil.

JB. These corporate trinkets originally celebrated the oil industry. Now, they symbolize geopolitical and environmental destruction. How do you navigate these conflicting associations in Morale Patch?

TS. They originally signified a touchpoint in innovation and various countries’ position in the world. In Morale Patch, they’re grotesque symbols of a human desire to make meaning from violence. They fuse propaganda and sentimentality.

JB. Does their link with violence make it hard to collect them?

TS. I feel bad about how much I enjoy them, mainly as representations of power. But I mustn’t get too close — much like with the ring from The Lord of the Rings.

JB. I imagine you sleeping surrounded by hundreds of paperweights.

TS. That’s the sort of thing I would do. As a child, I never had teddies, but I would get obsessed with objects — usually video games — and sleep next to them.

Mapping the Oil Industry in ‘Watchlist’

JB. The central piece in Morale Patch is a chess-like game populated with these paperweights. What does ‘Watchlist’ reveal about the oil industry?

TS. We often don’t understand why certain countries are allied — but oil is usually a missing part of that equation. Each paperweight is a stand-in for a country or an oil company. In the map, the color of the bases relates to different moments and terrains: the Arctic, oil spills, the Saudi desert, the North Sea. These are the places where the oil comes from and where oil wars are often fought.

JB. Does the layout of the map represent a particular moment?

TS. Multiple. You can see a stronghold of Gulf States represented by the terrain and paperweights from the region on one side. Then there’s a paperweight from Texas and another backing it up from America. This is the 1991 Gulf War. You also have an American paperweight and a Saudi one somewhere, which represent 9/11 — an unanticipated piercing of the American stronghold.

JB. You’ve also made coffin-shaped paperweights encasing broken pens. Some are adorned with the American flag. How do these play into the story?

TS. They represent the bureaucratic decision-making that occurs in the safety of the office, which leads to violence elsewhere. America and its flag are constantly entangled in this game of life, especially when it comes to the Middle East.

JB. Has the global relationship to oil changed since this historical moment?

TS. It’s still about one thing: Drill, baby, drill. In today’s climate, it’s about gesturing at a greener future without making consistent progress. Britain has put a lot of money into decommissioning oil rigs in the North Sea, but we’re still paying Norway and Russia for oil. I don’t see that changing any time soon.

Race, Childhood, and Legacy

JB. Let’s shift gears a little. You’re often explicitly referred to as a ‘Black lesbian’ artist. How do you feel about being labelled based on your identity?

TS. I got into a hole with that when I was acting in my films. Suddenly everyone was obsessed with talking about how I’m Black and a lesbian. It’s boring. And it’s restricting. When I was at Goldsmiths, people wouldn’t give me the feedback I needed because they didn’t want to risk seeming racially insensitive.

JB. Your father was a fashion designer from Ghana, and your siblings are both in the entertainment industry. It must have been a creative home.

TS. My dad’s business consumed the household. He was so ambitious.

JB. Do you draw a line from his fashion career to your work now?

TS. He was my model of a creative. He helped me start a brand when I was 16. We’d been to Ghana, which is heavily Christian. An exorcism was performed on me during that trip. I wanted to channel that experience into an atheism-themed brand, and he supported me. After he died, my relationship with him has been about finding success and trying to make him proud of me.

Looking Forward

JB. What are you learning about these days?

TS. I’ve become more spiritual. I grew up resistant to religion because I was forced into it, and it clouded my relationship with Ghana. But in a spiritually bankrupt society, we need more practices that connect us to something higher.

JB. I have one more question for you. What’s next?

TS. I’m feeling very present lately and know that I don’t need to prove myself as an artist anymore. I’m also working on a commission for Glasgow International next year. It draws on scrapbooks made by wives for their soldier husbands. These women used craft to contain war and violence. That’s what I’m exploring.

Tanoa Sasraku

Tanoa Sasraku is a Glasgow-based artist whose multidisciplinary practice spans sculpture, printmaking, textiles, installation, and film. Her work draws on landscapes, pigments, and minerals to explore personal histories, geology, and myth. Combining research with fine art techniques, she creates evolving works that resist fixed meanings. Sasraku has exhibited internationally, including at Spike Island and Vardaxoglou.

Joshua Beutum