What Braids Mean Across Time? Heritage, Resistance, and Reinvention

From ancestral codes to fashion runways, braids stand as cultural language and visual archive, linking heritage with reinvention

Braids as living geometry: how hair braiding encodes memory, identity, and design beyond appearance

Not every canvas is flat; some curve across the scalp. Braids are shaped through geometry, rhythm, and repetition, carrying a visual language that reaches beyond appearance. Each style is temporary in form yet continuous in practice, renewed across generations. Unlike artworks stored in institutions, braids endure through constant renewal.

They inscribe memory on the body, moving between personal expression and collective identity. Patterns preserve ancestral codes, survive displacement, and adapt in diaspora, functioning at once as archive and performance. Both intimate and monumental, braids travel from courtyards to city streets to fashion runways, linking heritage with reinvention.

From precolonial Africa to the present: Yoruba, Wolof, Himba, and Akan braids as systems of power, lineage, and coded knowledge

Across precolonial African societies, braiding structured identity long before written records. Yoruba and Wolof communities treated the head as document: braid patterns signaled age, marital status, spiritual role, and lineage. Himba women coated their hair with ochre and butterfat to mark life stages and social position. In Ghana, the Akan encoded symbolic meaning into hair using mathematical patterns that echoed kente weaving, applying a textile logic to the body.

These styles acted as visual codes designed to transmit meaning across public space. A child’s first hairstyle marked status. Ceremonial braids marked rites of passage. The scalp became a surface of geometry, echoing the same gridwork seen in architecture, beadwork, and cloth. Braids did not decorate. They structured.

Under slavery: cornrows as maps, seeds as survival, grooming as resistance

The transatlantic slave trade fractured these systems, but the braid endured. When names were lost and kinship systems dismantled, hands preserved knowledge. Oral histories describe how cornrows mapped escape routes and how seeds were hidden in plaits to plant in new soil. Grooming became covert resistance, a tactile language formed in the absence of speech.

That knowledge moved through repetition. It passed silently from scalp to fingers and back again. Colonial regimes sought to police and erase these practices, but braiding adapted. It stored what could not be archived elsewhere, building memory into form.

Diaspora in motion: salons, streets, and micro economies turning braids into urban visibility and intergenerational memory

In the diaspora, braiding carried memory into new geographies. The practice survived rupture, moving from African courtyards into homes and city streets across the Atlantic. Each braid held a trace of ancestry and a mark of the present, continuity achieved not through preservation but through repetition. Styles were worn, undone, and made again. This rhythm ensured survival in motion.

Braiding became part of urban visibility. In Harlem, Brixton, and Brioude, it marked cultural presence in the street, on buses, in schools. Salons emerged as hubs of exchange spaces where technique was taught, lineage sustained, and invention encouraged. Scholars such as Tiffany Gill have described these salons as micro-economies and cultural archives, places where labor, care, and artistry converged.

Salons as cultural archives: labor, care, and technique as intergenerational knowledge

Within these spaces, instruction traveled by touch and observation. Pricing, scheduling, and mutual aid created informal economies; playlists and conversation set community rhythms. The chair became a site of trust where techniques were honed, stories were shared, and futures were imagined a practical education in aesthetics, business, and belonging.

Art and performance: braiding as commentary on displacement and belonging

The practice has also been staged in art and performance. Carrie Mae Weems has photographed the intimacy of hair care as an act of kinship. Zina Saro-Wiwa’s films explore hair as narrative of diaspora life. Through these works, braiding appears not only as tradition but as commentary, reflecting on displacement, belonging, and renewal.

Across generations, braiding has held the tension between heritage and reinvention. It carries fragments of continuity from Africa while adapting to new worlds. The diaspora gave it scale—transforming a domestic practice into a cultural statement visible in streets, galleries, and media. A braid is individual, but in diaspora it becomes collective memory in motion.

Beyond hairstyle: braids as contemporary art, design, and politics runways, galleries, and collaborations led by Black stylists

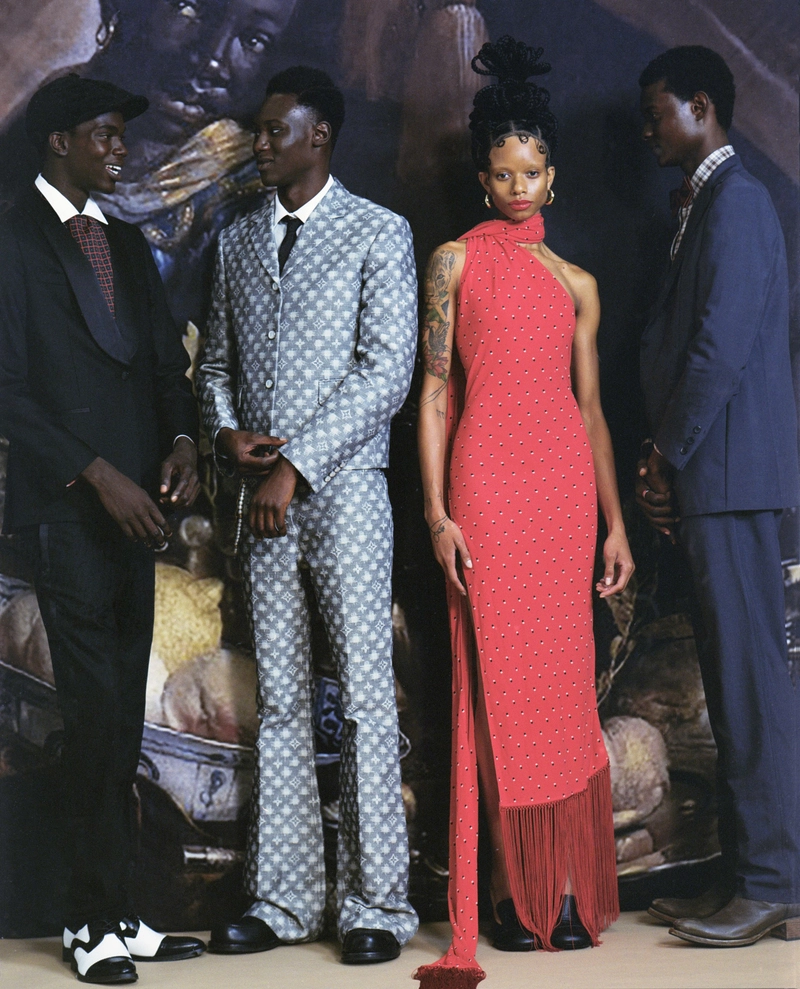

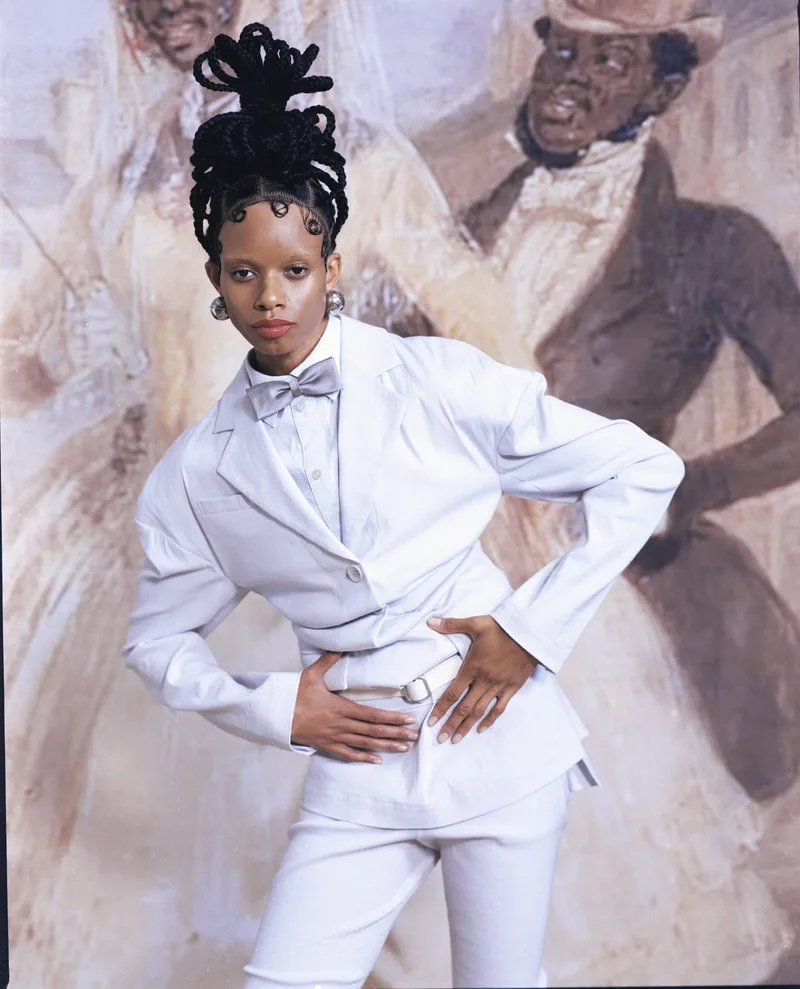

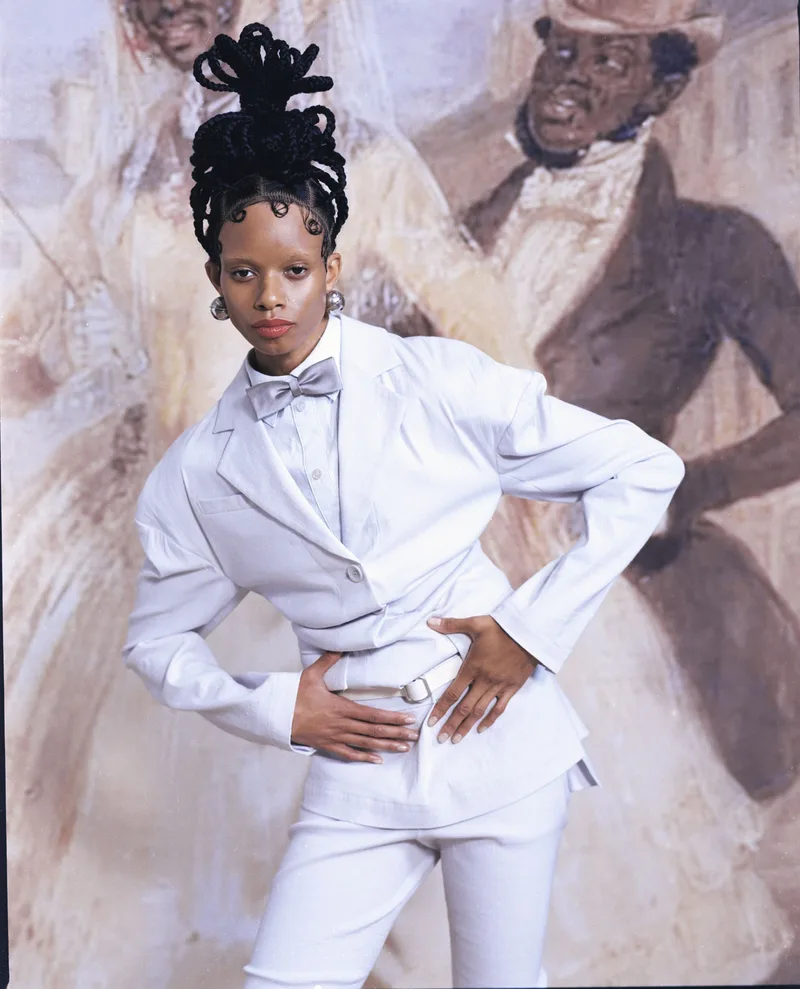

Braids belong within the language of art. Each plait is a line; each section, a gesture. Together they form compositions of order and variation. In contemporary culture, these forms are lived, staged, and theorized. Musicians like Solange have transformed braiding into performance, turning hair into architecture of identity across sound and image. Visual artists such as Lorna Simpson and Mickalene Thomas have worked with braids as material and symbol, placing them within the canon of contemporary art. Scholars like Kobena Mercer and Noliwe Rooks have written of hair as politics, aesthetics, and resistance, framing braiding as a cultural design system rather than surface style. These interventions position braids not as ornament but as archive and critique.

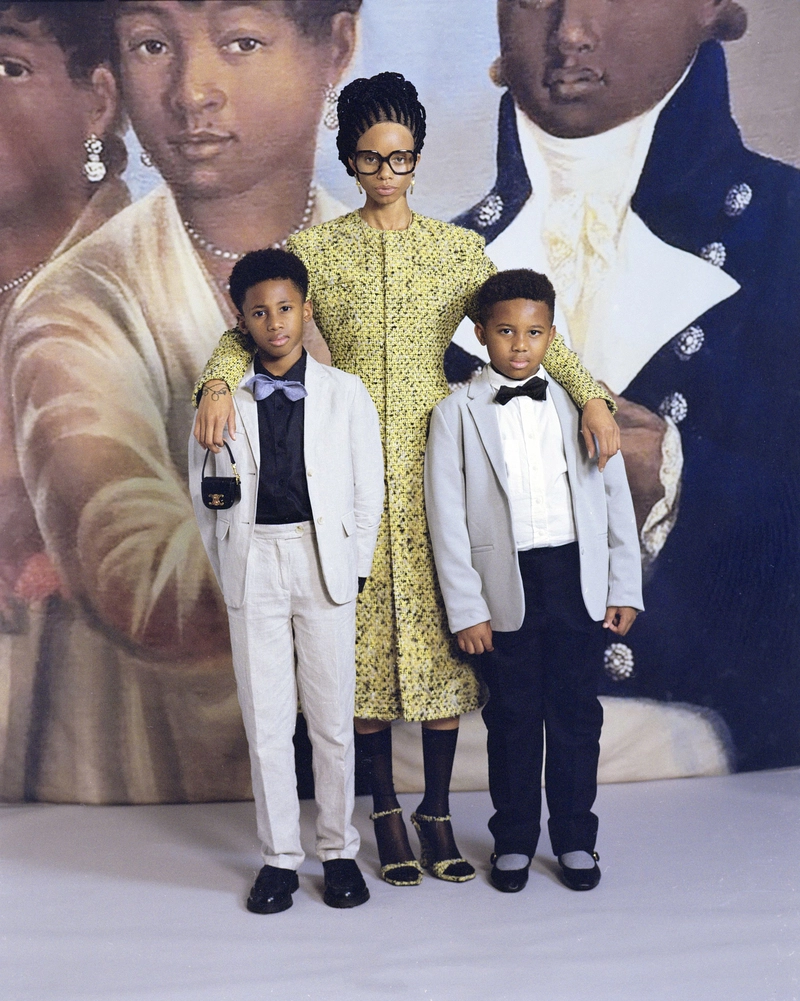

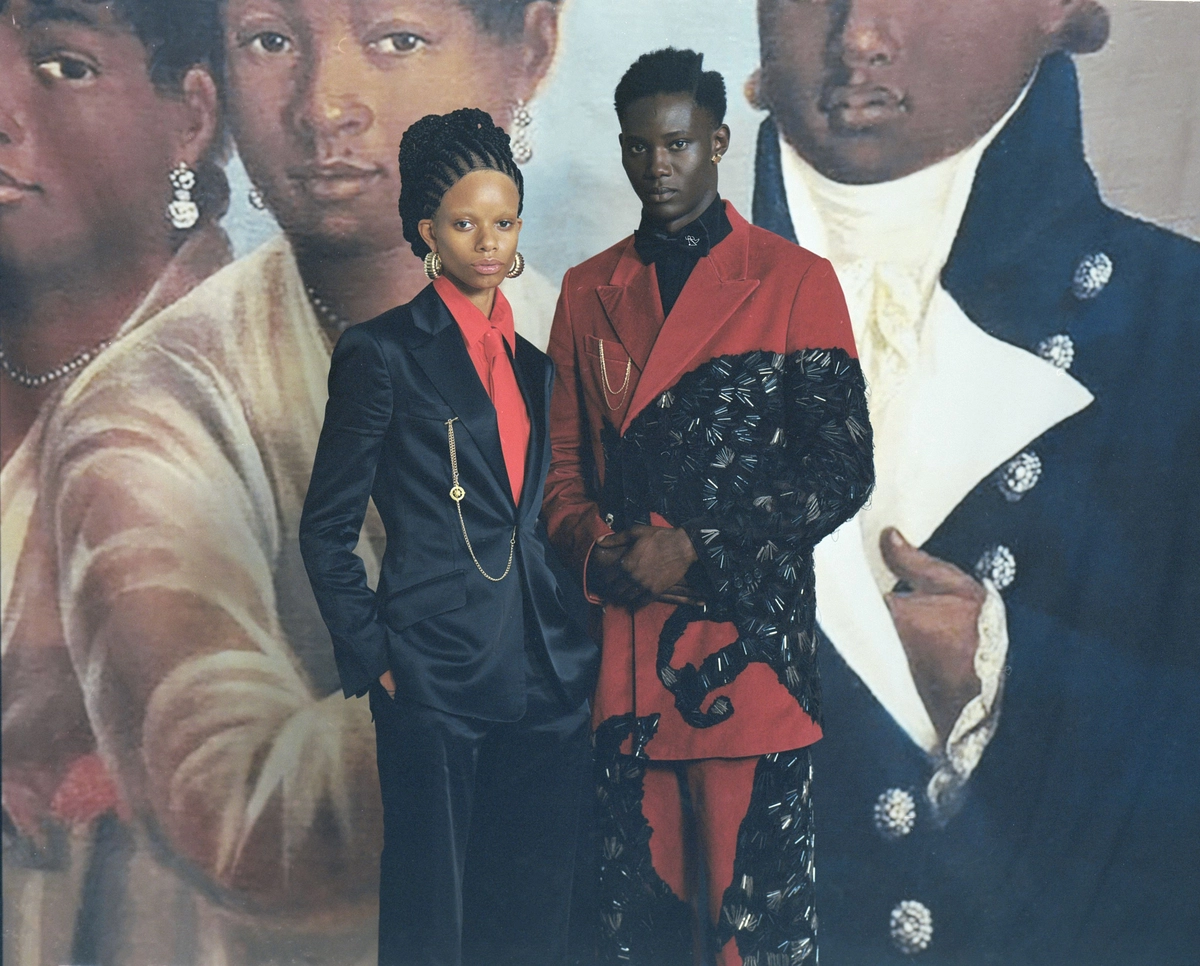

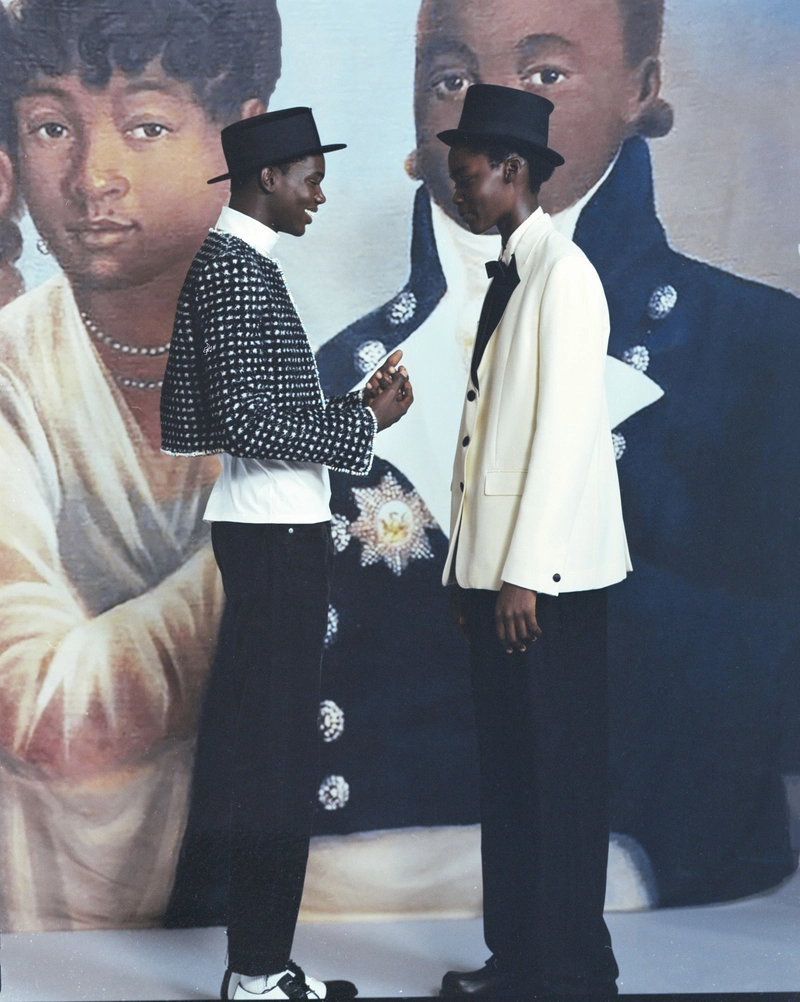

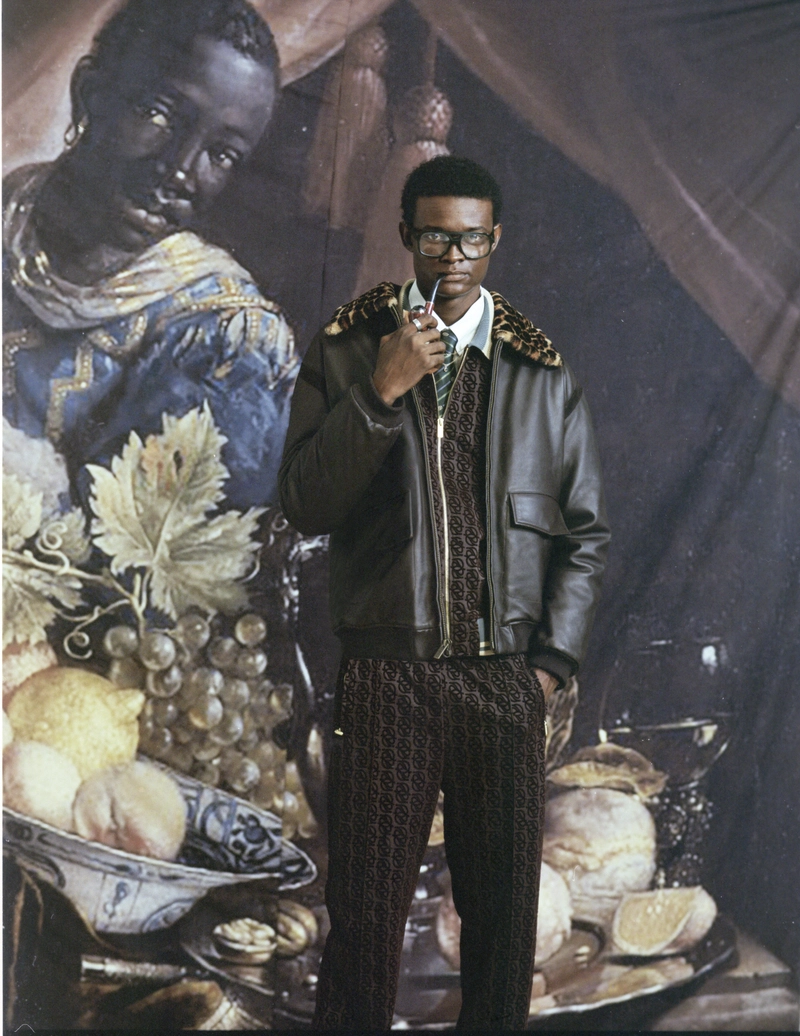

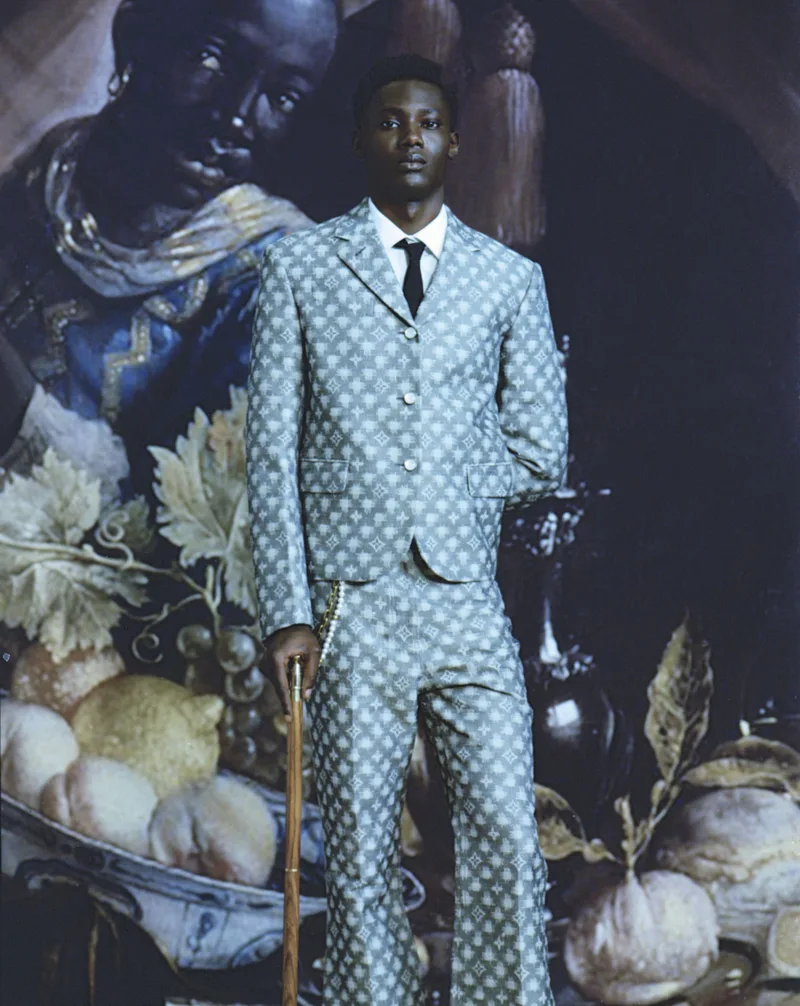

Fashion amplifies their visibility. Runways present them as structures. Campaigns emphasize their sculptural force. Editorials frame them as declarations. Yet their role in fashion is not only visual. Hair becomes a stage where cultural codes and histories collide. Designers have long borrowed from braiding traditions, sometimes as homage, often as appropriation. The response has been contested: what looks like ornament to some carries centuries of meaning to others.

Appropriation vs collaboration: centering Black stylists to transform fashion narratives

In recent years, collaborations with Black stylists and artists have shifted this dynamic. Figures such as Jawara Wauchope and Shani Crowe treat braiding as sculpture and performance, working with global fashion houses while grounding their practice in community. Collectives and platforms from Lagos Fashion Week to independent salons frame braiding not as trend but as lineage. In New York and London, designers and stylists increasingly center Black voices in the creative process, reframing appropriation as collaboration.

Scale and temporality: from single plaits to sculptural volumes, from hours of making to the memory of undoing

Braids expand across dimensions. At their smallest, they are single lines. At the next, they form repeating patterns. At their largest, they rise into sculptural volumes that reshape the head. They also unfold in time. Like performance, braids are process: hours of making, weeks of wear, hours again to undo. They resist permanence, leaving only memory of labor and rhythm.

Braids expose the sophistication of practices often dismissed as ordinary, dissolving the boundaries between craft and art, heritage and design. They are architecture in strands, performance in repetition, archive in motion.

A moving archive: why braids are living design systems beyond museums minimalist rigor, Bauhaus modularity, everyday performance

Braids remind us that some of the most intricate design systems exist outside institutions. They do not stand behind glass. They live in streets, in salons, in daily life. They carry the rigor of Minimalism, the modularity of Bauhaus, the temporality of performance while remaining woven into the everyday.

Benedicta Addoteye