Zegna, district, manufacturing: is this the only story we need?

It is not fashion. It is work. The “well made,” the cloth that stays in the wardrobe: the Zegna method and what Northern Italian enterprise still teaches

Zegna, Biella, worsted wool: a district built around a specific craft

Wool comes from the Biella area. More precisely: Biella became a district because it specialised in worsted wool. That matters. Worsted is not carded wool. Carded wool has its own Italian geography—Prato, with a different logic of production, texture, and industrial history.

How much is still left to say about these manufacturing districts? They are not a decorative chapter in “Made in Italy.” They are commercial and industrial history. They are also a form of collective life: productivity plus civil society, held together by work.

Districts formed for mixed reasons. Geology and climate shaped some of them. In other cases, the starting point was wealth in a few hands that turned into a possibility for a whole community. The rhetorical, almost utopian question is whether new manufacturing districts can still be born today. Many believe the task is defensive: protect what exists. New districts, they say, cannot be created anymore.

People living within variable distance ended up doing the same job. Different entities, different firms, then a shared movement started. Companies began to act as a single organism when it was useful. Ideas met other people’s experience. More crucially, workers moved. Craftsmen and operators went from one firm to another for practical reasons—wages, timing, conflict, opportunity. They carried mastery with them. They carried tests, failures, fixes, and habits. Skills circulated.

A district is a living social fabric. It is a permanent proving ground for manual ability and intellectual attitude. Districts do not grow inside the city. They grow in territory—what Italy calls provincia—where manufacturing historically had access to natural resources, rooted traditions, and human bonds that hold under pressure.

Zegna on the runway: the district as legend, casting as the profane element

Zegna can be a symbol. A title for a story. It can hold that cultural and historical imagination. Every runway show repeats the legend of the district. Biella, worsted wool, and the other natural fibres that the old looms learned to handle. Cashmere coming from India. Threads “worth gold” coming from South America. Linen. Cotton. Then the hope of hemp.

Hemp is not a mood-board fibre in your text. It is a thesis. Hemp is the only textile fibre you call sustainable without caveats. It could be cultivated in Italy. If it were Italian, it would set a benchmark that the national industry could not match with anything else in sustainability terms. The argument is not about trend. It is about an industrial option that Italy keeps postponing.

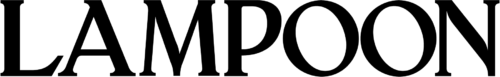

A Zegna show works like a good song: it gets everyone to agree. Then the eyebrow lifts at the casting. Male casting, the choice of faces and bodies, a variable degree of fluidity, a heterosexuality that becomes interesting exactly when it is put under discussion. Elongated silhouettes that can collide with the background Zegna embodies in the collective mind: solid, robust manufacturing quality.

The models come with angular faces. Shoulders as corners. Panthers or gazelles. Executioners and victims. Angels and demons. They look like extraterrestrials from a future dimension. In Zegna, casting becomes a break in coherence. Almost everything else stays familiar—classic menswear, the “proper family” wardrobe. Casting is the dissacrating factor. It gives modernity through aggression. A creative risk, close to a slap. It turns the show on like a hydrogen engine.

Zegna, narrative, collective imagination: the country villa, the city home

Once you absorb the scratches of casting, the narrative remains. It consoles. It reassures. It looks like an interior. A house wardrobe. A large villa salon. The walk-in closet of the commendatore—owner, patriarch, count. Boiserie framing a fireplace. Persian rugs layered over rugs, like bedspreads sliding from a canopy bed. The bourgeois country house that sometimes goes to the city. If this were London, it would be the club. This is Italy: from Biella you orbit Turin, then above all Milan.

There is a link between provincial life—villa, garden, woods, factory nearby—and the city apartment. What you are writing is not only style. It is a way of living, read through Zegna. The Biella entrepreneur, the patriarch, chose new architects—names that later became masters: Gardella, Caccia Dominioni. You cite them as references, not as verified attributions. The Zegna man looks for a rationalist aesthetic, anchored in the contemporaneity of his own time. No décor. No Mongiardino. No Rococo. A lived-in house. The human trace is simple: a book dropped on the floor on Sunday afternoon, when eyes close for an hour.

Today, the Zegna man is a boy. The people holding the reins are young. Zegna is trying to become a brand for a new generation, not only for those who know how to choose—and can afford—the quality of worsted wool, a coat with a weight that recalls solid wood.

The larger question is cognitive and cultural. How does the intellectual solidity of our parents evolve—when the brain trained on books, when even television was treated as a laziness not to overuse? How does a sense of measure in aesthetics survive when it used to be fed by long reading, page after page? We live in a world where attention has been cut down by continuous hypnosis on social media.

The challenge for Zegna—and for all of us born in Italy—is to find and cultivate measure in our culture, with Milan at the centre of it. Reinterpret the Milanese code that comes from work and courtesy, good manners and listening. Travel, yes. A novel is travel too: it moves through cities and nations, time and astonishment.

Zegna’s runway is not only admiration for an entrepreneur’s wardrobe, for a decent man. It is an invitation to reactivate ourselves. To work. Nobody cares about elegance anymore—unless elegance returns as a synonym for intelligence.