Hyperlocal installations produced with CO2 in mind – A Feral Commons (or: A Forgotten Place)

For A Feral Commons, Muhannad Shono studied unnoticed ecologies in Dubai’s urban Alserkal Avenue. He applied his rebellious manifestation philosophy to the industrial Al Quoz area

A Feral Commons: fostering symbiotic relationships through public art

Rather than following the tradition of touring, A Feral Commons features site-specific artworks that address local environmental issues creatively. Curated by Tairone Bastien, the project spotlights nature’s resilience in diverse, dense urban environments in the UAE, Jamaica, and South Africa, while fostering symbiotic relationships among city dwellers and their living space. At a deeper level, the project suggests we reconsider our relationship with non-human beings to tackle climate urgency and save humanity.

The inaugural pilot project, a co-commission led by Alserkal Advisory and the Global Cultural Districts Network (GCDN), prototypes a new framework for responsible public art commissioning. Collaborating with Urban Art Projects (UAP), the environmental footprint and impact of each installation are accounted for.

Environmental benefits of hyperlocal art

Typically, a group of arts organizations works with a lead producer to jointly finance artwork, which will typically circulate between them. The works in A Feral Commons don’t tour, eliminating environmentally damaging transfers, specialized packaging, and any associated risks. The participating stakeholders agree to a curatorial brief and commit to supporting the commissioned artists’ visions in dialogue with their unique localized context. This includes navigating issues of site control and securing appropriate authorizations.

The “hyperlocalism” approach to public art suggests that artists can tackle major challenges quicker by addressing them in ways tailored to the specific needs of their communities. It evokes site-specific community responses to and critical engagements with global issues. In identifying research and engagement as goals for A Feral Commons, each of the three participating districts formed a learning community, engaged in strengthening peer networks, and contributed useful knowledge to their professions.

Measuring art’s impact: Artwork Ingredient List, Public Art 360

A Feral Commons addresses the impact of each installation, utilizing UAP’s tools: the Artwork Ingredient List for calculating carbon footprints, and Public Art 360 for evaluating the social, cultural, and economic impacts on communities and their environment. These tools serve as a baseline to quantify what responsible commissioning could look like.

Through considerations of site control parameters, stakeholder engagement, and shared commissioning responsibilities, a new intelligence evolves to inform future art making in more circular and sustainable ways. All learnings will be published and shared upon the release of the final installation.

Muhannad Shono: «obsessed with the idea of rebellious manifestations»

Lampoon spoke with the artists whose work kicks off A Feral Commons. Muhannad Shono, driven by creative rebellion, brought installation The Teaching Tree to the 2022 Venice Biennale, representing UAE. In a video published prior to the co-commission, he expressed, «My existence as an artist has been a response to attempts to limit and restrict human imagination. I’m obsessed with the idea of rebellious manifestations.»

Unnoticed, thriving ecologies in Dubai

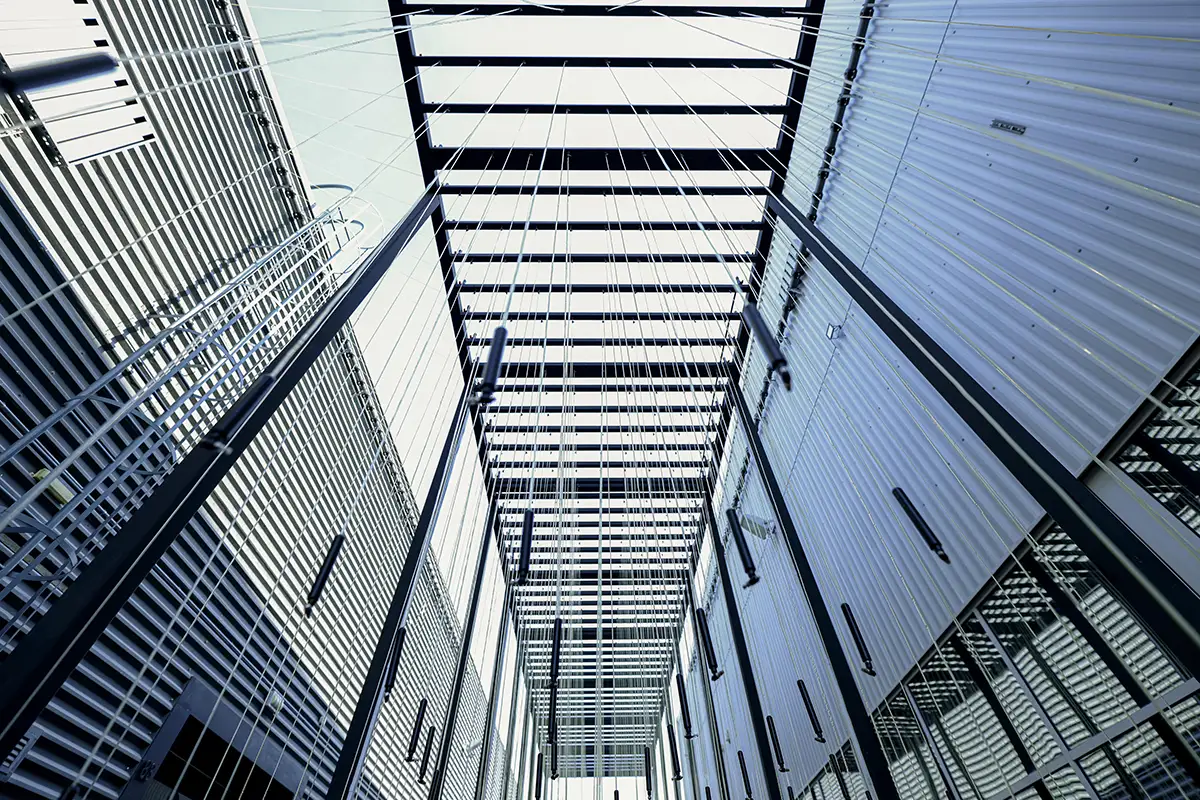

For A Feral Commons, Muhannad Shono studied unnoticed ecologies in Dubai’s urban Alserkal Avenue. He applied his rebellious manifestation philosophy to the industrial Al Quoz area, particularly examining greenery emerging from the AC units – a familiar sight. Shono reflects, «I sought feral traces of nature to question what ‘feral’ means in Dubai. I observed these AC units with ecologies we mentally discount every day.»

Despite the severe and arid conditions of the industrial environment, remarkably varied plant life thrives under and around air conditioning units outside of the buildings. In an area with very little rainfall, these plants grow and flourish in unexpected places, nourished by water condensate that drips from the AC units operating non-stop, producing especially heavy flows of water in the hottest summer months.

Shono: «Each AC unit hosts its own unique ecosystem, with basil and watermelon in some areas and thorny, poisonous plants in others. I attempted to attract bees with basil, but they haven’t shown up yet. It takes time. The underlying question is: are we merely observers, or must we actively engage with our environment? In a landscape where life is scarce, including cats, bees, and birds, our responses must transcend typical human behavior.

It baffles me how these systems are not standardized in architecture. AC units’ condensed water is wasted down the drain. Why aren’t smart or modular systems utilizing it for flushing toilets or irrigation? In a world where there are plenty of AC units, it’s frustrating that we fail to see their potential.»

A Forgotten Place kicks off A Feral Commons: «a superhuman empathy is necessary»

To conclude his research project, Shone constructed an art installation titled A Forgotten Place which extracts water from AC units and channels it to nearby plants, thus initiating an ecological cycle.

Positioned between warehouses, the installation features a network of transparent irrigation tubes collecting water from the AC units inside. Visitors can walk around and observe how the pipes channel the otherwise wasted water to irrigate seeds in the soil beneath and between the bricks, fostering circular plant growth.

Though Shone usually keeps the process of his installations hidden, maintaining a sense of mystery, he made an exception for A Feral Commons. He used transparent tubing to narrate the story of the single humble drop of water: traveling down from the invisible systems above our built environments, it holds the potential to irrigate the earth and save humanity.

Shono reflects: «Thinking of feral animals and plants often occurs in a simplistic manner. We desire to collaborate with them, but we cannot think like them, nor can we communicate with them. Inter-species collaboration requires us to step outside of ourselves – a superhuman empathy is necessary, akin to the empathy people already have for a tree. Incredible collaborations could emerge from that.»

Sustainable art in Dubai: «it offers a solution to the problem it contributed to»

Why Dubai, an international symbol of waste and pollution? The city relies on free desalination, a process also utilized in other Gulf cities, which poses significant environmental challenges due to waste disposal (salt, hazardous chemicals) and energy consumption. Tairone Bastien: « One discovery from the project was the significant water output from AC units. Although not potable yet, it sparks discussions about alternative water sources.»

Shono himself adds: «The work is reproducible because it utilizes off-the-shelf irrigation systems accessible to people. My hope is that it becomes not just a teaching moment, but rather an open-source, a desperate piece of information, serving as a guide or manual.» Shono’s AC units, man-made machines, facilitated the development of cities in the desert, but the same technology allowed desertification to happen. “It offers a solution to the problem it contributed to.»

Humanity must become more feral

Shono’s unconventional approach to Dubai’s suburbs, working with AC ecologies that were not planned for, diverges from conventional urban planning practices. «In Dubai parks and public spaces are manicured and hedged for aesthetics, so we can have our picnic, play with our kids and draw more tax capital in. There is no honest concern for nature as something essential or collaborative. It’s a flavor of all cities we live in: they’re struggling to be authentic.»

Shono studied plants that don’t obey the rules, something humans typically want to rid themselves of as they foil their (city) plans. There is intelligence in the wildness of plants, animals, and waterways that ideally are respected and collaborated with – as Shono did for this project. They respond to their environments to find ways of surviving, which holds a lesson for us: in confronting the climate emergency, humanity must become more feral.

Al-Khidr: the ultimate plot twist inspiring A Forgotten Place

Shono connects his project to a character from Arabic mythology, Al-Khidr (green (wo)man), depicted as a head with no body, with plant matter coming out of the nose and mouth. Al-Khidr is a symbol of regeneration, rebirth, resilience of nature, and the cycle of death and rising again. Shono: «It is as if we’ve tried to silence this character, that will inevitably return as the ultimate plot twist. If we were to abandon our urban spaces, they would quickly be reclaimed with a different kind of urban planning — something natural and undeniable.»

Camille Chedda (Jamaica) and Io Makandal (South Africa) for A Feral Commons

The following artwork for A Feral Commons is by Camille Chedda, a lecturer and visual artist focusing on postcolonial identity. Representing Jamaica, she worked in Kingston, overgrown with plants commonly inhabited by bees. She presents an artistic apiary, a mini-industry for community members to learn a new skill and produce their own honey.

Io Makandal inaugurates the third and final project of A Feral Commons. Creating for South Africa, she stays true to her living sculpture practice, working with Johannesburg’s Victoria Yards. Her installation centers around the overlooked Jukskei river that runs through the precinct, positioning it exactly at the point where the river meets daylight and where the first impact of human mismanagement, sewage, and pollution takes effect. She aims to activate that space along the river for civic engagement.

Tackle climate urgency with public art

Tairone Bastien: «Cities are a flashpoint for current and coming climate emergency – places with exploding populations and struggling infrastructures that are inadequate to deal with even greater fluctuations in weather. The three districts in the project, all within the Global South, where climate disaster is already present, are recognized as a part of these struggling urban ecologies.»

The process of public art commissioning largely neglects the urgency of addressing the current climate emergency, a topic explored in Lampoon’s Boiling Issue. We can no longer afford to imagine future actions but must take concrete action in the immediate term. A Feral Commons interprets this new phase by upending a new logic to the arts.

Shono: «The co-comission taps into unnatural man-made systems to resuscitate the natural. It is an involuntary, inevitable response to something that is immediate, that is desperate, and it’s also unnatural.»

Tairone Bastien: «Does art merely pose questions to people, or can it also propose action or concrete countermeasures? The project counteracts climate emergency and proposes a challenge to the artist: to create work that goes beyond symbolism or conveying a message about climate change or narrating the story of feral ecologies. Instead, the aim is for the artworks to be active participants within the ecologies they are embedded in, generating outcomes beyond mere aesthetic value, serving a utilitarian purpose, and fostering relationships.»

Anna Roos van Wijngaarden