Absurdity, masculinity, and a nude Cary Grant: Kurt Kauper’s take on painting

«All great paintings are great whether it’s Giotto or Picasso because of the way the volumes move through space». In conversation with American painter Kurt Kauper

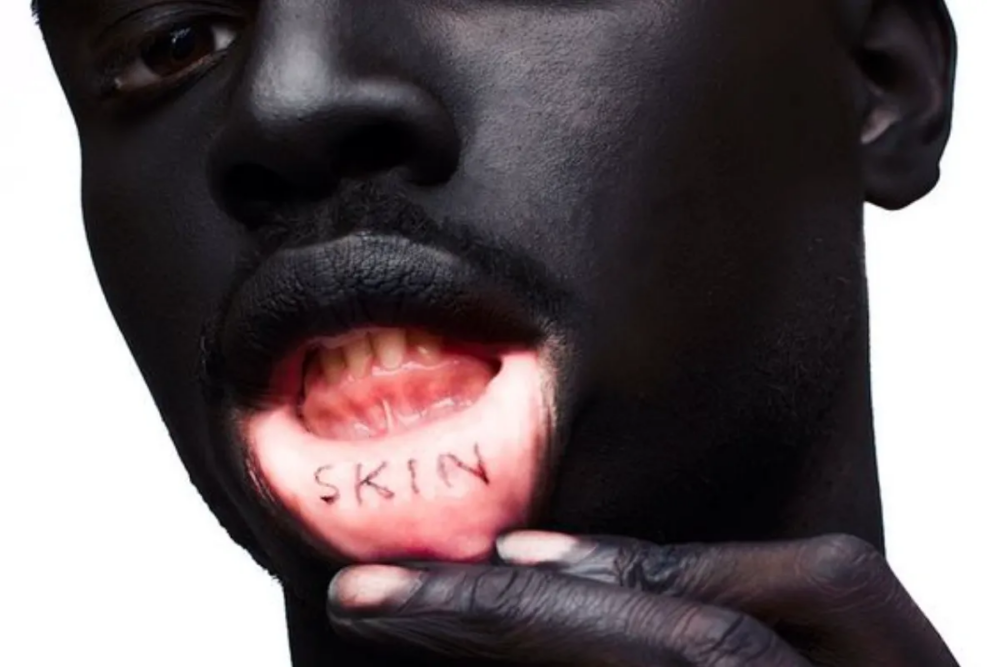

Kurt Kauper – Traditional masculinity

What is masculinity? What does masculinity look like? How is it presented in art form? Kurt Kauper investigates and explores the idealized form of masculinity, from his own admiration and childhood notion of the term to today’s evolution and its ambiguous markers.

From the athletic male nude and portraits of hockey players to intimate moments of men grooming, Kauper goes beyond the everyday introducing almost a feel of escapism within his work. Trained in a traditional manner, painting and its long history have influenced Kauper’s artistic research and practice, which has come full circle in recent years as he comes to accept the term of formalism to describe his work, yet his own version and description of the style.

«The university art program at Boston University in the eighties was by the standards of the time considered traditional in that they taught in a modernist figurative way. The big heroes of the school I went to, not for me, but for the school were Max Beckmann, and Oskar Kokoschka. I have recently been thinking about the training because when I came out of that program, they really emphasized formalism. I remember one of my teachers saying that all great painting is great whether it’s Giotto or Picasso because of the way the volumes move through space. Obviously negating any historical content basis, initially, I rejected that idea but I’ve come around recently to thinking of myself as a formalist».

West Coast influence in Kurt Kauper’s works

From New York to Los Angeles, Kauper was exposed to a different and emerging art world on the West Coast. Sacrificing sleep as a means to be able to paint during the day and work the overnight shift at the Plaza Hotel, moving to Los Angeles broke the routine and placed the artist in the right place at the right time. Kauper enrolled at UCLA in a period when the art faculty was experiencing radical change, not only in its teaching staff but also in the art system which supported the students on the outside.

Between New York and Los Angeles

«On a whim, I went to visit a friend in Los Angeles, and again on a whim, I applied to UCLA as a way to get out of a rut, out of the cycle in New York. I didn’t know that UCLA would become this prominent grad school in the time that I was there, but I lucked out. Lari Pittman started teaching there, who was a huge influence, and Charles Ray, although when I started I didn’t know who he was in 1992. Paul McCarthy was also there, and Chris Burden. A whole group of older faculty members had retired, and the school, therefore, redefined itself. It opened up what I thought was possible for figurative art.

We felt that we were part of a moment, this was the early nineties, and the art world in the US had taken a significant economic downturn in the late eighties and early nineties. There were many startup young galleries in LA at the time, it all seemed very accessible, being part of a gallery didn’t seem impossible. It was a vibrant and rich art community in Los Angeles, that didn’t feel in any way out of reach. I was in LA from ’92 to ’96. I later got a teaching job in Boston so I decided to come back to the East Coast, and commuted from New York. I always wanted to go back to New York».

Instilled with a newfound energy and morale boost post-UCLA, Kauper aimed to make New York his home and the center of his artistic research, production, and exhibition. Kauper presented his first solo shows in 1997 at Jay Gorney Modern Art, NY, and at ACME, Santa Monica; a representation of his artistic network on both sides of the country. The following year, his work was seen by Jeffrey Deitch thanks to an article in Flash Art, and he offered for the two to work together. Kauper presented several solo shows at Deitch Projects until its closure in 2010.

Rejection of formalism

When observing Kauper’s paintings, there is a distinct traditional aspect from the use of portraiture and even at times use of known figures as the subject against the monotonal backdrop. Kauper reflects on the journey his painting has taken to arrive at its present-day destination, «I rejected the idea of formalism. I bring up this term with younger artists and they don’t have a clue about what I’m talking about. I remember being aware of this term as an undergraduate, but perhaps because we were all much closer to a period when there was a real belief in formalism. I have always loved the history of painting, which has been an important influence on my work. If I had to choose one favorite artist, it would be Ingres, one of my favorite historical artists.

Coming out of BU, I rejected the idea that my work could be interpreted as formalist, I was influenced by my teachers at UCLA, who insisted that artists should work with and offer a conceptual framework. I remember Lari Pittman saying during orientation that he expected students to have a thriving practice, meaning an active studio, but backed up by the theory, he didn’t mean theory in the conventional grad school syllabus sense because that’s never been part of his sensibility. He expected serious thought and framed it linguistically. In my work, I would include the ideas and the narratives associated with the work first and then talk about the work itself as if it were a result of that thinking».

Engagement with the history of painting

Looking back and studying the history of painting as a means of understanding his own work, Kauper is aware of his influences and how the final presentation can be interpreted in several ways, there is not one set discourse surrounding Kauper’s practice and this in itself gives the artist food for thought. «I recently had to give a presentation on my work, and I realized that if I think about where my work comes from, all of my work is an engagement with the history of painting.

I always think about how I can take this form that I love, which is traditional painting, and representational painting, and somehow modify it so that when viewers encounter my works they feel like they are looking at a well-known language but in a somehow estranged way. As I am making paintings, all types of meanings suggest themselves and develop, that’s where the ideas and the narratives come from. They don’t start the work in the way that we think of concepts, in a linear fashion. I consider myself a formalist, where I think of the form and how I am going to modify it. That’s the underlying motivation for me. I do not consider myself a formalist in the sense that it’s entirely about the pure forms of painting».

The protagonists of Kauper’s paintings include both famous and anonymous figures, including hockey players, the Obamas, Cary Grant, and opera divas, such as Maria Callas. «With the Cary Grant paintings, I had just finished a series of paintings I call Diva Fictions, which I showed with Deitch Projects. I had no idea what I wanted to do next, I remember that I was in Paris at the time and I was going through all these possibilities, and for whatever reason, it occurred to me to paint Cary Grant nude. That didn’t come from any identifiable sequence of thought, it just occurred to me. I had been watching a lot of Cary Grant movies for the previous five years, and I had really gotten into Cary Grant, but there wasn’t a cohesive thinking process. I found it a funny idea, and it was a little absurd, I liked the idea of absurdity in painting».

The absurd in Kauper’s compositions

Absurdity is a prominent theme within Kauper’s compositions, from the use of well-known figures in pop culture and society to their placement within the image, whether they are nude or feel awkward in their pose and gesture. An element of absurdity causes the viewer at times discomfort and unease from the inability to read the painting easily. Kauper maintains a balance between the absurd, the awkward, and the recognizable language within the painting.

«One of my favorite paintings is Jacques Louis David’s The Oath of the Horatii, which is incredibly absurd when we look at it now. We look at the language that was used to create meaning, it is both incredibly persuasive and absurd. I liked the idea of making a painting that operated that way. There was also a gesture of admiration, but I knew that it would be interpreted as somehow iconoclastic but I liked all those tensions. Sometimes the absurdity bothers me. I recently did a lecture, which was posted online and a comment read, “It’s almost as if he’s mocking his subject more than admiring them”, and I find that this is related to the idea of absurdity. My favorite paintings are often absurd. I love Ingres and his paintings are absurd, I love John Currin and his paintings are all about absurdity. I love Francis Picabia, which has an element of absurdity in his work».

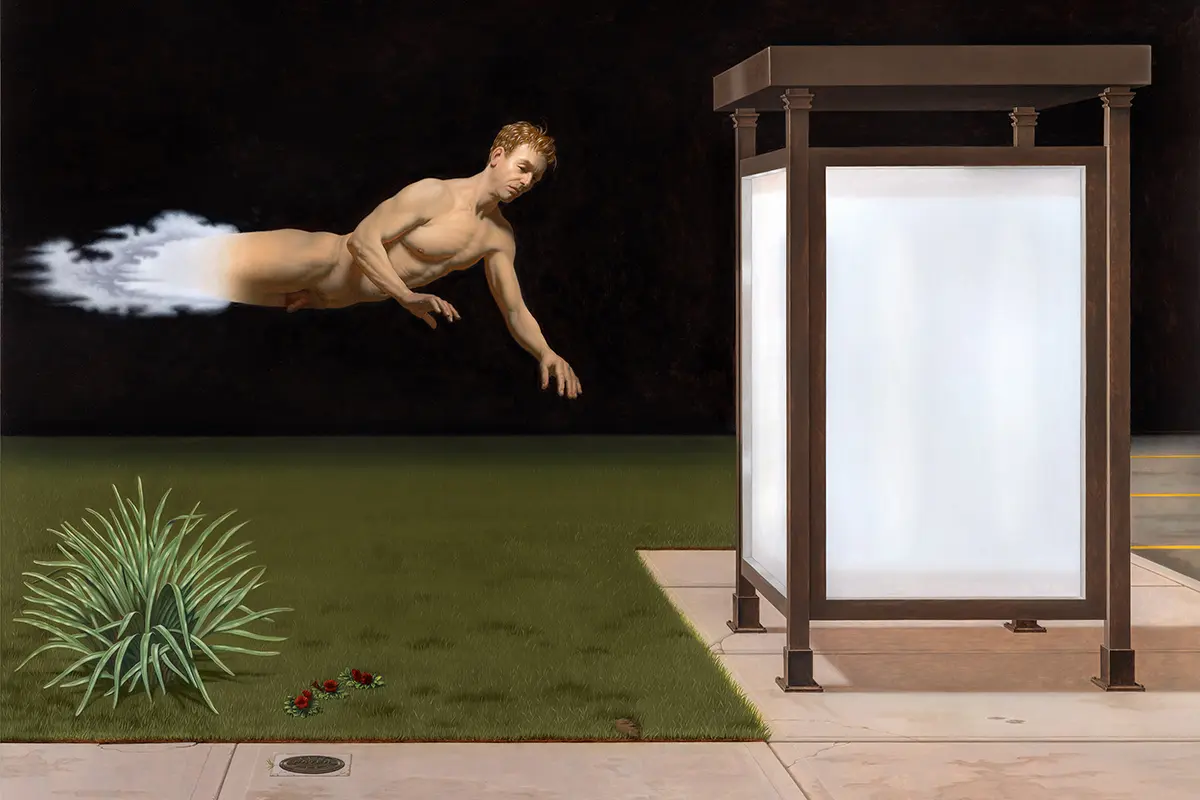

Kauper’s Bus Stop work

Moving away from his commercially successful paintings, such as the Cary Grant series, Kauper has contemporarily been working on a slightly differing style, introducing a fantastical aspect, increasing the absurdity, and moving away from reality. Bus Stop (2020) which is part of the Fantasy series of works, consists of a nude male, whose lower legs have transformed into clouds, floating towards an isolated bus stop against a dark background.

Again, the absurdity is clear from as simple as the question, why would this figure require public transport when he is capable of flying? «I recognize why people would call this work surrealist, which I don’t, but again I understand the reference. With that painting, which I am working on a body of work right now, I had done a series of paintings in 2018 of Women which were shown at Almine Reich Gallery and I was tired of doing these paintings that I called iconic, in the sense of a single figure. It presents an image to a viewer, where these figures point to a determinative meaning, which is unavoidable, I wanted to get away from working that way.

Bus Stop is based on a Sassetta painting at the Louvre, called The blessed Ranieri frees the poor from a Florentine jail (1437-1444). It’s impossible to tell what is going on, there is Ranieri, a monk, floating through the air, gesturing at the prisoners who are escaping through a hole in the wall. I have always been drawn to that painting. Always in the back of my mind, since first seeing it thirty years ago. I had an impulse to make a painting riffing off the figures. I didn’t have any clear narrative reason, I almost didn’t want one, I wanted to make a painting without any determinative content that could be associated with it and see where it went. That’s the first painting that came out of those, I am working on another painting based on another figure».

American Dream no more

The well-dressed man, 1950s-esque attire, and slicked back hair, the his-and-hers portraits of the first Black American President and the First Lady; a concept which has long evolved since its primary use, certain aspects of Kauper’s works recall the look of the American Dream or its lack of credibility as a concept in modern-day America.

«I am interested in identities that are in an in-between state. I like indeterminacy. Something I have always loved about Cary Grant is that you can’t quite identify exactly what you’re dealing with. It was famously unclear if he was gay or straight, what was his accent, was it American, or European influenced. A synthetic identity was created, and all of that was interesting to me. We would never say he was not masculine, he had a certain type of masculinity, but it’s an ambiguous type of masculinity, it’s not stereotypical. All of this contributes to an idea of the American Dream, the idea that you are supposedly able to make yourself which you can’t anymore. It’s fiction».

Clean cut men

Clean cut. «For the Watching Men series, I have always had an interest in men’s clothing, the way men’s clothing exists within a relatively circumscribed set of options. Culture is changing and this is changing, but conventional men’s clothing exists in this set of options. This was true in the 1930s and is still true today. I liked the idea of using clothing as language in these works, even though I never dress that way. I guess there is an aspirational aspect to it.

The figures in my work are associated with the fetishization of well-groomed men. I am interested in expectations of masculinity, and my perceived failure to fulfill them. This is what instigated the Hockey Players series, I grew up in a blue-collar Irish Catholic town outside of Boston, and hockey was how a boy was defined, their ability to succeed in that realm, I was aware of my failure not that I regret it. Whether that’s playing hockey or being perceived as a successful male, there is less discussion on the expectations of masculinity».

Directly influenced in his teenage years, Kauper took note of his gay uncle and partner’s view of masculinity, its presentation, and finally its differing meaning from person to person. «I remember my grandmother saying after visiting my uncles in New York, ‘Those men spend so much time in the bathroom every morning grooming’, a complete mystery to her. I feel that this stayed in the back of my mind. There was this idea that men shouldn’t do this for some reason».

Kurt Kauper

American contemporary painter who lives and works in New York City. Kauper graduated from Boston University in 1988 and completed his Master of Fine Arts at UCLA in 1995. He has been the recipient of the Pollock Krasner Foundation Grant in 2001, 2006, and 2019. He has taught at Princeton University, and Yale University School of Art, and since 2005, Kauper has been an Associate Professor of Art at Queens College, City University New York.