Amit Berman turns pain into softness

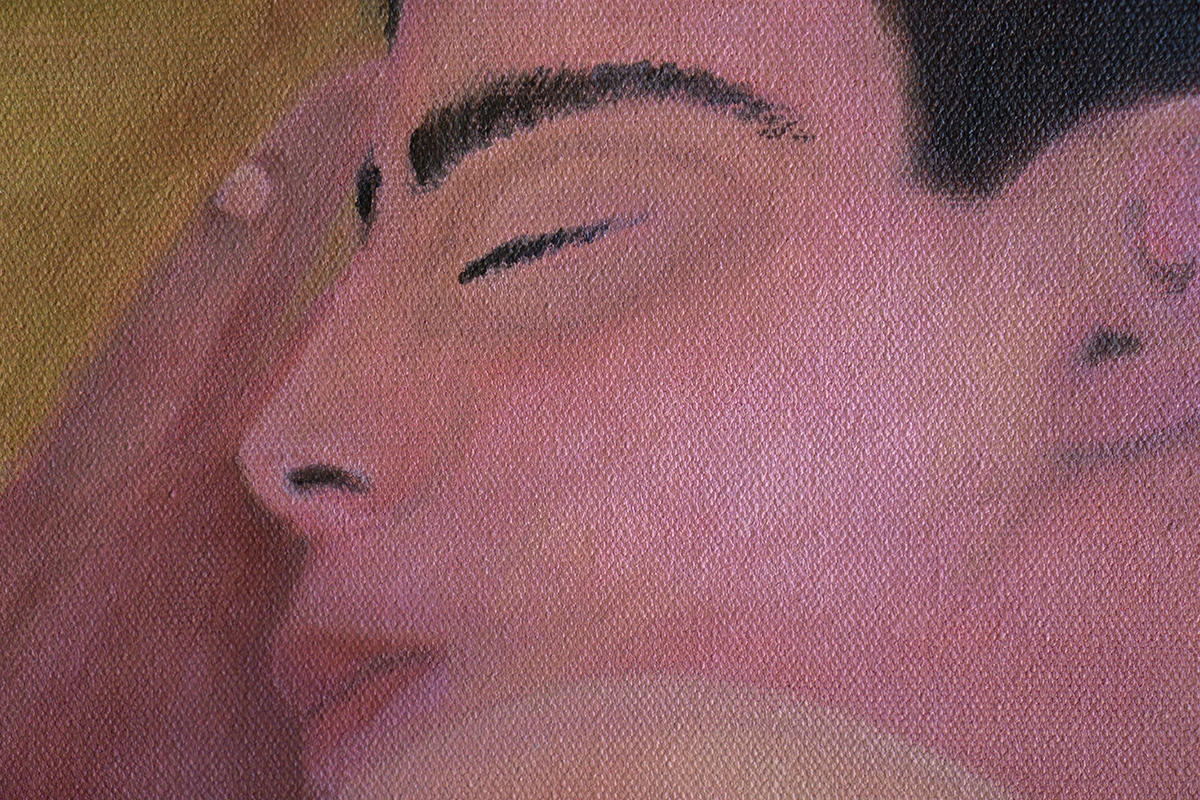

I work in a messy, dirty way. Beneath the roughness of grainy canvas and cadmium underpainting, Amit Berman stages male nudity as a zone of negotiation – trauma and tenderness, sex and self-approval

The stain that stays – Three paintings by Amit Berman Berman for Lampoon, on what the body remembers: from childhood violence to tenderness

Trauma is depicted as stain: something that clings to skin, memory, light. One painting shows the imprint of a fork pressed into the body – a reference to a moment of childhood violence, reimagined with ambivalence. The scene is part surrender, part detachment, rendered with a surprising softness that resists easy emotional legibility. Another work shows a figure lying in darkness, caught in a beam of light from above. It’s a suspended, in-between moment – about intimacy, visibility, and the slow movement out of trauma toward self-recognition. The third painting takes place in a surreal, Romanesque shower: a tiled space with an arched, antique ceiling and glass panels that half-obscure the figure. Like Marsyas before Apollo – the satyr flayed for daring to challenge a god – the figure stands exposed yet veiled, caught in the tension between visibility and vulnerability. The stance is proud yet ghosted by the barrier. Like his recent solo show Softened Edges his work complicates ideas of masculinity, privacy, and performance.

Across all three paintings, Amit Berman treats the body as a site – marked by experience, memory, and desire. Stains appear as beams of light, dark underpainting, as bruises, as the fog of glass. These are works about aftermaths: the visual or ephemeral residue of something that already happened. There is no spectacle here, no drama – just surfaces marked by time. While his work borrows quietly from art history; from classical figuration to Romantic nature and 20th-century expressionism, it resists nostalgia. It’s about what remains.

Roughness, layering, and cadmium red: Amit Berman on his technique, self-taught practice, and material honesty

Amit Berman: The surface has to be rough. There’s depth in it, and I am trying to show that through the layering of the paint. I choose a rough surface, starting with a quite intense color, cadmium red purple. The initial part of the painting even feels a bit violent to me. From that moment on, I am trying to soften it, to reach tenderness throughout the complexity. I try to show imperfections. As a self-taught artist, my work was never “perfect” or classical in a way. You can see that process over the years. My earlier work was much less polished because I was trying to express myself without limits and without the skills. Now I can be more precise about the rough elements I choose to keep while telling the story.

Jemma Elliott Israelson: For Lampoon, roughness is a value – not a flaw. In art historical terms, it reminds me of Caravaggio’s dirty feet on his holy subjects, or Leon Kossoff’s thick, muddied paint. Your paintings are physical – from the forms of the figures to the architecture that surrounds the body. Your materials – canvas, paint, color, surface – are not just tools, but part of the content.

Sustainability and slow production: how Amit Berman balances environmental consciousness with artistic practice

Amit Berman: At the beginning, I worked mainly on paper, which left room for the surface’s texture. I used more impasto, searching to show the essence and physicality of the material. After a while, I started painting on a refined linen. It was almost smooth. I was doing a residency in LA last year and couldn’t find the same material on time. I went back to using more grainy surfaces – and I am grateful for the turn. Within that surface, I’m trying to search for tenderness and harmony. I’m working with the oil to create that.

I strive to live and create with a moderate environmental impact. While sourcing sustainable materials is often challenging, I address this by producing less and minimizing waste. I try to avoid discarding materials during the study phase, and I almost always complete each painting I begin. In Italy, maintaining a more sustainable lifestyle came relatively easily; in Tel Aviv, however, it has proven to be more difficult.

Interview with Amit Berman: I work in a messy, dirty way. Trauma, self-mythology and the chiaroscuro by Caravaggio

JEI: You don’t shy away from difficult subjects. It’s not that they’re depicted in a visceral way, but they can be heavy.

Amit Berman: The painting with the fork is from a memory of real violence, but I’ve composed it with this gentle prodding into the skin. I tried to transform pain into a moment of gentle immersion. To enlighten it. I depict my daily life without hiding the mundane, that’s how I show roughness and honesty.

I work in a messy, dirty way. Many realist or figurative painters work in a more organized way and separate the paint. I’m so much in control in my life and then in my practice I let this go – I even mix paints directly on the canvas. Nothing is sterilized. As we speak, I’m working in a studio in the countryside and everything is free, rough, and messy.

It’s funny that you mention Caravaggio as well, since I just saw the show in Rome (Caravaggio 2025 exhibition at Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini in Rome – editor’s note) and without thinking it’s the first time I’m working with a kind of chiaroscuro. Also in the bed painting, there is a tiny painting which hangs above our bed, I’ve painted it a few times. It’s a little reproduction of a Caravaggio work. I carried it with me from my apartment in Milan to Tel Aviv.

JEI: John Berger wrote, The way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe. When you’re painting a scene from your own life – a trauma, an intimate moment, or a memory – how do you keep it from slipping into self-mythology? How do you stay honest with the image?

Amit Berman: The personal is the starting point. The self-mythology, as you called it, is present, but I keep the door open for the viewer to engage with the painting. I want to transform those intimate moments into a narrative in which others can resonate with. I search for titles that are open for a subjective interpretation.

Between Milan, Tel Aviv, and Hong Kong: the role of place, displacement, and migration in Amit Berman’s visual language

JEI: You live and work partly in Tel Aviv – a city that’s in flux, physically and politically. Where does the city show up in your paintings? Is your studio a retreat from that, or a container for it?

Amit Berman: After a few years working in Italy and using it as my main reference, I realized I wasn’t confronting the challenges I was facing in Tel Aviv. You might say that some of it can relate to a sort of queer dislocation. I was always escaping. I couldn’t feel at ease. When I did paint Tel Aviv – It was always our apartment, where I felt safe. Italy just felt like an ideal in a way, a place free from confrontation. Lately, something moved in me and for my last show at Alon Segev I started going back into Tel Aviv interiors: my studio, the Tel Aviv museum bathrooms, local hotels. Places where I could now feel present. My studio is a safe space. It’s far from other studios, and I can be isolated. The city can be exciting, but what I love the most about it is our house, my studio and the sea.

Hong Kong has shaped my eye. I worked for an airline, and it was my favorite destination. At the time I was into studying architecture and spent most of my time there sketching from life, the shapes, the lines, the chaos. It’s quite an organized chaos. it wasn’t about palaces, it was about structure, intensity, density. At that point I was drawing architectural sketches. Milan is where I started painting, which makes it a meaningful place for me. My first two years of oil painting were in my apartment there. The city isn’t very green, but it has these walled garden courtyards. During COVID, the parks were closed, and I started painting wildflowers, flowers that were unreachable. This became the language of my paintings.

Why Amit Berman’s nude bodies aren’t eroticized: confronting taboo, religion, and self-exploration through oil painting

JEI: Nudity in painting carries history – from classical sculpture to the male gaze. In your work, the body is often exposed, but never performative.

Amit Berman: When I started painting, the use of nudity came from a search for self-approval. When I was living in Milan, I had a complicated relationship, and I was looking for validation through my work. Over time, I found an interest in exploring the tension between exposure and concealment. I find the body to be the most natural and beautiful form, which holds tension and tells a story.

There’s still a taboo, just as everywhere else. The connection between body and nature inspires me a lot and I try to convey that longing for nature through my work. I could be a bit too conservative in a way, but I try to break that through painting. The canvas is where I can explore what I desire or what I hide.

Between detachment and confrontation: Judaism, and emotional distance in Amit Berman’s work

JEI: Do you think that taboo has something to do with religion – like a hangover from conservative Jewish ideals?

Amit Berman: I didn’t get it from Judaism. Every religion does that as it mostly holds to more archaic ideals and norms. It’s not about provocation. It’s about using the body as an organic form. My work deals with intimacy. I search for honesty and there’s nothing more honest than a naked body. Even if the body is never fully exposed.

Sex relates to honesty. You never really see it in the work, but you feel it. It’s an act of confrontation. I use it as a way to explore ideas of distance, closeness, migration and pain. In my last show, I was thinking about remoteness and intimacy. It started with sex, but expanded to my upbringing, to being queer, being Israeli, being always abroad. I’m searching for safety and honesty.

Amit Berman: painting queer identity

JEI: Similarly, your work isn’t about homosexuality – but it doesn’t hide it either.

Amit Berman: I live my life as a normal person, whatever that means. I paint my partner a lot and while doing that I am talking about queerness. I’ve often felt outside the queer community, I got hurt by people in the community a few times, I guess that made me feel vulnerable while staying near. I detached myself in order to keep safe. There’s a lot of isolation in the work. As the time went by, I realized that so many of my friends in Italy are part of the community, but in Tel Aviv I was isolating myself.

JEI: That isolation is clear in the painting with the body on the bed. The body is not only alone, but has a kind of inter, paralyzed form. In the work you use shadow and light to push both the eye and narrative of the work across the canvas. You also often paint surfaces that are fogged, stained, or scarred. What is it about the stain – as image or idea – that draws you in?

Amit Berman: Painting for me is a way of cleaning something, but not fully. I like to leave traces of what was there. Imperfection is the story I am trying to tell. There’s also violence and pain in the work. With the choice of themes and the underpainting’s color. I’m trying to hold the stain in the painting, not to forget it.

Being queer, being Israeli – an interview with Amit Berman

JEI: In your shower painting, the body is fragmented – obscured by glass, almost dissolved by steam. Why resist showing the full figure?

Amit Berman: Not showing the full body creates tension, between closeness and distance. That’s true of sex, roughness, everything. I want to invite you in without exposing everything. There has to be a mystery, even in a naked body. The body is the protagonist in my work, but it still needs to hold some enigma.

JEI: Whether or not it’s explicit, painting the male body – queer, damaged, exposed – is political. Do you see your work that way?

Amit Berman: These days, the body is political. If I don’t have the safety to show my work, I can’t detach from that.

JEI: In terms of being queer, or being Israeli?

Amit Berman: Both. Being queer isn’t accepted everywhere, even in places we thought were advanced, we’re going backwards. As an Israeli, my voice is in my paintings. For a long time, I was partially hiding that I am Israeli. It is something that I can never change, it’s not a choice, just like being queer. I have a lot of criticism for the government and its actions, I am devastated by the amount of pain, injustice and suffering.

Jemma Elliott-Israelson

Jemma Elliott-Israelson (b.1994) is a Milan-based curator and art advisor specializing in post-war and contemporary art.