Anthea Hamilton: Oil makes everything slippery – soap brought the idea back to earth

Anthea Hamilton reflects on the role of tactility in her installations, from quail eggs and bondage rope to plush pumpkins and perfume

An interview to Anthea Hamilton on recontextualized objects, sensory installation art, and the politics of texture in contemporary practice

Speaking with London-based artist Anthea Hamilton on a picnic table outside the Royal College of Art in South Kensington, she draws attention to the twisted contours of a silver necklace, noting how they contrast with the texture of her loosely knitted sweater. As she talks, she absentmindedly runs her fingers across the grain of the wooden tabletop beneath her hands.

Research, archives, and found objects: the material foundations of Hamilton’s art

Fresh from the opening of Soft You in Rome, Hamilton is immersed in research for two upcoming publications, combing through the library of the Royal College. As she sits, she retrieves a photograph from Neo Furniture by Claire Downey—an image soon to be added to her continually expanding archive of found objects.

Hamilton’s relationship to the archive is what sets her practice apart. Known for large-scale installations and surreal site-specific performances, her work is grounded in the accumulation and reinterpretation of eclectic materials. During a recent studio tour, she presented an assemblage of metallic garden flowers, plush toy pumpkins, rocks collected from the Scottish highlands, and a book by Gaetano Pesce.

Gaetano Pesce, performance, and the body as sculptural form

Pesce himself was a pivotal influence in Lichen! Libido! Chastity! (2015), the Turner Prize-shortlisted installation that included Hamilton’s recreation of Project for door (1972)—a monumental 18-foot golden sculpture of a man’s buttocks provocatively spread open. In 2018, Hamilton collaborated with Dior’s Jonathan Anderson on six costumes for The Squash at Tate Britain. These outfits nodded not only to the diverse shapes of the vegetable itself but also to 8 Clear Places, a performance by Erick Hawkins first staged in 1960.

Recontextualizing the everyday: Hamilton’s visual language of cultural residue

Hamilton’s layering of pop-cultural and historical references—alongside her instinct to incorporate everyday objects—forms a deeply personal visual lexicon rooted in recontextualization. Building on Antonin Artaud’s notion of a physical knowledge of images, her installations resist purely visual consumption. Instead, they are intended to be felt – impressions that register in the body as much as in the mind. Her work is textural experienced through skin.

Soft You and the sensory life of objects in Hamilton’s Roman exhibition

For Soft You at Fondazione Memmo, Hamilton invites viewers to reconsider the weight and symbolism of the ordinary. The exhibition constructs a dialogue between Rome, Shakespeare’s Othello, and the meticulously curated physical space of the gallery. In Calzedonia (Hot Legs) (2025), a frieze of human limbs offers a reflection on gendered dynamics evoked by the Italian capital’s many hosiery boutiques. Meanwhile, Shibari Desk (2025) explores the tension between form and stillness, using Japanese bondage ties as a sculptural motif to express pace and contrast. A scent designed in collaboration with decolonial perfumer Ezra-Lloyd Jackson permeates the space, challenging assumptions around the supposed neutrality of smell. The result is a multi-sensory meditation on the inner lives of objects—a suspension in “the void”, where their inherited cultural meanings are rinsed away.

Texture, perfectionism, and the pressure to be political in contemporary art

In the weeks following the debut of Soft You, I sat down with Hamilton to discuss her obsession with surface and sensation, the looped nature of referencing in today’s accelerated cultural climate, and the unspoken expectation for artists to be overtly political. What emerges is a nuanced portrait of a practice that embraces ambiguity, leans into complexity, and remains unwaveringly devoted to the experience of touch.

Anthea Hamilton on scent, oil, soap, and sensory contradiction – the interview

Anthea Hamilton: I’m an oil person. I recently took a bath and put on these oils. It was a bit of a nightmare because everything was greasy—myself, the bath, my hands. I couldn’t do anything. It seemed like a beautiful idea and the bottle was beautiful – but it was just pure oil. So maybe a bar of soap, which I find interesting in its dry state. It’s got a scent you can’t see just by looking at it.

Neither of my parents were outwardly creative. They were practical in how they went through the world. I remember my dad would hang these calendars that my mum would buy with kittens on them—very stereotypical. He would always find the biggest, sturdiest, roughest nail and brutally hammer this dainty, little thing into the wall. I remember finding it so distasteful, but now I respect it. If you want to hang something, make sure it doesn’t fall. Why be delicate when you only have a moment to express yourself? An attitude of roughness is a disproportionate act beyond the realms of necessity.

The Squash and selecting sculpture through touch

JB: I read an interview about your preparations for The Squash. You said that when you were choosing sculptures from Tate Britain’s collections to accompany the performers, you were more concerned with the sensation on the hand than the images themselves.

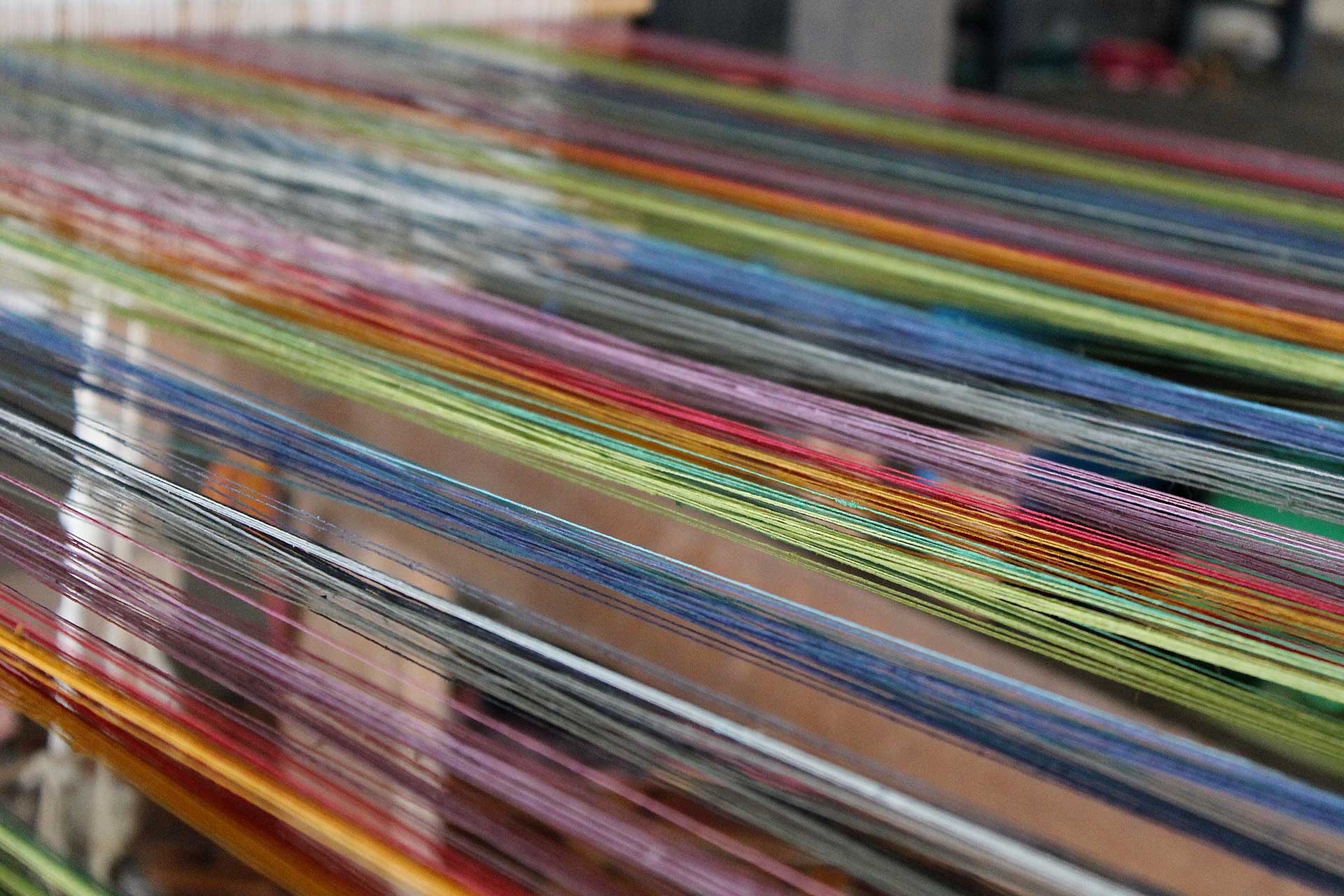

Anthea Hamilton: I’m led by texture. I probably camouflage that in the image, but my work is primarily about texture. It’s a way to experience time, the friction on the surface of a material, running your hands across it. I have a library of materials, and their textural speed helps me decide how they fit together in a collage. It’s a marriage of the visual and textural.

JB: Textural tensions run throughout Soft You—notably Shibari Desk (2025).

Anthea Hamilton: For Shibari Desk (2025), I worked with a Shibari master, and I inundated her with questions about why she would use such a length of rope. I thought it was for the size of the body, but it became clear the more knots you make, the longer it takes to tie or untie. Plus, the roughness of the rope controls how long it takes to make each knot. It’s about the speed of the act. That piece was installed onto a table covered in quail eggs. It took three and a half months.

Interview with Anthea Hamilton: precision, performance, and artistic control

JB: You’re almost mathematically precise—you once spent a month deciding on the width of the grout between tiles for The Squash. There’s an element of any performer, body, or found object that’s outside of your control.

Anthea Hamilton: I want to provide a high-quality, considered environment for the performers. When deciding the width of the grout, I didn’t want them to feel like it dominated them or that it was too light. It needed to be just solid enough to carry them through six months of their performance. Kata in Japanese Kabuki theatre. If something goes wrong in the performance, if you’re practiced with a foundational support, you cannot truly fail.

At the Basel Social Club, we auditioned many people but chose only two. Even if there were gaps in the performance, we decided that was better than spending all this time to fill it with something that wasn’t quite right. We only want the people who make the whole thing work.

Since being an artist is already quite obtuse, why would you compromise? There are other professions—like if you’re a designer, it’s about listening—but if you’re an artist, the idea of compromising an artwork doesn’t make sense.

JB: Have you felt compromised before?

Anthea Hamilton: I have had big budgets: that’s almost a compromise because you can get washed away in the spending. Otherwise, the compromise never comes down to the work. It’s often on the self, or you may allow yourself to be compromised. I can imagine it’s a compromising situation if you’re asked to function in a space where you’re not fully trusted or if people just humor you without truly understanding the work. That said, I’m sure institutions like Tate Britain wouldn’t ask me into those situations if they weren’t ready for what I can offer.

Time, references, and the physical knowledge of images – the focus of this interview to Anthea Hamilton

JB: You’ve cited Antonin Artaud’s “physical knowledge of images” in your work. What does that idea mean to you?

Anthea Hamilton: You can take it literally. I know what it feels like to hold an iPhone. If I see an image of an iPhone, I know the weight, I know its slipperiness, I know what it is. Sometimes when you see an image, it speaks of something more. It affects one in a visceral way—a non-verbal, non-visual function. It speaks to our other senses and our feelings, probably through semiotics because our culture has constructed the images for us.

JB: There’s also the idea that we’re trapped in a loop of referencing other references until the original image—or reality—is lost. With that in mind, where you position yourself in relation to your references?

Anthea Hamilton: We’re in a moment of meta-referencing, but I come from a time when there was a more straightforward way of looking at things. I just look at things for a long time. It’s not about the speed of a reference; it’s about the deep wavelength of an image. I normally keep images with me until they make sense—I’m like a processor. It’s not about forcing a meaning but about collecting items and seeing what makes sense. I also think about the power of images—which images get to stay, which images get lost, and how they function as expressions of what’s dominant in the culture. Historically, at least. Now, there’s a mass of images or a weight of data rather than an image itself.

Referencing the past as a strategy for clarity and resonance

JB: Is that why you tend to draw on images from the past, rather than the contemporary?

Anthea Hamilton: I’m just not quick enough. The contemporary is now, and I’m too much within it to understand it. But looking at something from the past, it’s already settled. I can find what’s quintessential about it. I was listening to someone talk about social policy and she was saying that certain answers kept coming up in her questionnaire. Those answers became the melody she needed to understand. That resonated. There are certain things that just make sense, and they become the references we reappropriate—from the 1980s to 1990s to now. Maybe, I’m referencing how we reference.

JB: That idea touches on Soft You, which explores a “return to zero”.

Anthea Hamilton: My work is often linear—I have a mathematical way of thinking. The quantum. Rather than pushing forward, I feel a need to reboot every time. When the work is complete, I go back. I don’t feel like I’m making progress, just creating new iterations or different expressions of what I have to say. It’s like travelling far, only to end up on the same street. After accepting that my experiences look like expansion and contraction back to a similar point in loops of complexity, I realized you could reduce that to something minimal and take it somewhere else. We often think about zero as none, but it’s not a lack, it’s a space. A void. In that vein, the museum is also a material. My thinking goes beyond the realm of the object. I’m very much thinking about the context.

Artistic responsibility, activism, and the politics of resistance

JB: Should artists be activists?

Anthea Hamilton: I find that sentiment to be quite undoing. I have a sensation of constant failing, not knowing how to un-fail within the system we’re in. That’s not because of my practice, but my situation as a person who lives in a city, who contributes to these issues through my daily life. My role is like any other person’s, whatever their job.

JB: How do you approach that role through your work?

Anthea Hamilton: I don’t get asked that often. I have a will that advocates for non-compliance. Understanding the rules and knowing how to work around them is political. Even if it’s in an art environment—as opposed to a street protest—that doesn’t make it any less disobedient. Things need to happen in as many parasitic ways as possible. You need people on the inside to understand how the system works and to be able to come back out and say that isn’t right. My work is showcasing a model of what different worlds can look like from within the institution.

JB: Do you feel a pressure to perform being overtly political?

Anthea Hamilton: People are often looking for a performance of artists making work about race. I’ve tried to resist that because I’m not impressed with the language around it. There’s also an element of visually misreading me, like looking at me and assuming I love mangos. To view my work through one lens is reductive. Daniel Day-Lewis doesn’t get pigeonholed—well, he does, but for being Daniel Day-Lewis. I want to be pigeonholed for being Anthea Hamilton. Nothing less.

Environmental limits, contradictions, and the vegetable as a metaphor

JB: Let’s touch more on environmentalism. Do you consider sustainability in your processes?

Anthea Hamilton: I do, then there’s usually a point where I completely screw up. I must stay true to what my work needs to be and do my best within that framework. If I need to make something from leather, I’m going to do that. Then it’s bad because people flaunt so much environmental damage. Sometimes I want to say, look at what Jeff Bezos is doing. We shouldn’t compare ourselves to these people—they’re the least normal. I do limit myself.

JB: There’s a fixation with nature running through your work—The Squash, the butterflies and flowers in Soft You, the recurring motif of the body.

Anthea Hamilton: A vegetable is growing. The internal life of that object has got nothing to do with someone in their garden or their ideology. It’s just doing what it wants to do. It’s a vegetable. It’s busy with its own affairs and we don’t understand them at all. We can understand nature only from a humanistic perspective, which is wrong. It’s a synonym for Western power, where the importation of crops has changed the natural environments of other countries. There’s a human fantasy about how the planet functions. We’re doing a lot of damage to it, but we’re not all there is. When we’re gone, it will still be here. In whatever form.

Fashion as material and the ideology of the body

JB: After high-profile collaborations with Jonathan Anderson, campaigns for luxury brands, and your recurrent use of clothing in your work, you’ve been positioned alongside the fashion industry.

Anthea Hamilton: Fashion is fast, and I appreciate the designers who love the speed. Seeing that in comparison to my tortoise pace is interesting. By the time I’ve gone to the library, whole collections have come out. To make something work on the body – I respect fashion for that. When I use fashion as a material, it reflects an ideology, but to the same magnitude as a tile or a wallpaper I choose for a room.

JB: An emphasis on fashion requires a consideration of the body.

Anthea Hamilton: The bodies I use are often beautiful young men. It’s a classical body, which opens a discussion around dominance and the dominant body. That’s where the campness comes into it, because holding these bodies up as the ideal is nonsensical. They are attractive. I tend to work with people who know how to use their bodies, and quite often those people are good-looking. Plus, I wanted people who could understand the weight of being stared at and not being taken for the complex humans that they are on the inside because of how they look. This was the case for The Squash. When they put the costume on, they could relate to feeling similarly objectified in whatever way by an audience who doesn’t always offer themselves the tools to look at things with complexity.

JB: While you’ve mainly avoided using your own body in your installations, you have used the silhouette of your legs as a recurring motif across your career.

Anthea Hamilton: Yes, my legs are not doing anything. When I made them in my 20s, using my silhouette was a defensive move. There’s no indication of ethnicity within them, there’s no indication of wealth, there’s just the freedom of being strong and young. I’m aware it’s a female body, but within popular culture the female body is almost a free sign.

London as a tactile, layered, and formative landscape for Anthea Hamilton

Anthea Hamilton: Born and bred in London. Plus, everything that I take for granted in London does not exist anywhere else. My work is the way it is because I didn’t have to question too much about the world I knew. If I had grown up in the countryside, there would have been a different framework I would have had to see and adapt to.

First, London is an old city. Because of the bombings in World War Two, there are contrasts of glass and brick, brick and stone. It forces an understanding of the will of the city to change over time. You can see the priorities London has as you move between areas—like Bishopsgate. You’d hope that these structures have been built in the most effective way, but sometimes it’s the opposite. Council estates are built with people in mind—more of an idea, actually—but they never work.

So, if I’m on a deadline, I’m at Studio Voltaire making decisions. Then it’s a lot of the time on the computer. I can look for ages or I get other people to help me. Other days I will go to the library, like today. The studio is my base, but I’m not always there. Travelling through London is part of the studio practice.

Learning, ageing, and the quiet patterns of artistic growth

JB: It’s been almost a decade since you were shortlisted for the Turner Prize, and you’ve been a practicing artist for over twenty years.

Anthea Hamilton: When you get older, you realize that time has passed and you’re still busy with the same affairs. Maybe that’s what it means to have a “return to zero”. There’s something about getting older and becoming a parent that can be so boring. Or maybe I’ve missed the moments of having fun. I was speaking with a friend yesterday and she said that being in your twenties was so intense. I don’t think it was intense to me. I wish it were.

JB: There’s an expectation that the twenties are a time of drastic development.

Anthea Hamilton: I always knew myself. Even when I was younger, I had faith in my capacities. Now, I’ve seen people who have doubts about themselves, which I’m lucky not to have. It’s that I’m comfortable in my own company. I’m chilled. Though I do see others get more done because they’re nervous.

I learned that a good companion plant for a pumpkin is a borage. I planted a squash on the balcony. It’s quite measly, but there was this thing growing next to it. I looked it up and found out that they support each other quite well. It always comes back to accompaniment.

Joshua Beutum