The jacaranda blossoms fall behind a misty window. The strum of a nineteenth-century guitar gently breaks the silence. Julian Bede, founder of Fueguia 1833, leads into its creative and productive universe

Pretoria in South Africa is known to be the City of Jacaranda – at the time of flowering, the city appears tinged with blue due to the huge number of blue-flowered trees emerging from buildings, gardens and boulevards. The Jacaranda is also widespread in Kenya, South Africa and Australia – it is being cultivated extensively for the decoration of city boulevards in all climatically suitable areas. As it is considered a lucky charm, it is often placed at hospitals and maternity clinics. The plant also reaches heights of 30 m. The flowers are gathered in terminal clusters – each flower is five-lobed in the shape of a long tube, with a blue to purple-purple corolla. some species have white flowers. The fruits are flat or elongated oval capsules containing small winged seeds. The wood of various Brazilian Jacaranda is also used for the construction of body parts of acoustic guitars: this wood, with its bright reddish colour, is often called ‘rosewood’.

Jacaranda, Fueguia 1833

The jacaranda blossoms fall behind a misty window. The strum of a nineteenth-century guitar gently breaks the silence. From music to a perfume: Julian Bedel was inspired by this plant for the creation of the fragrance Jaracanda. The fragrance reproduces the characteristic sound of a vintage guitar and makes the silence disappear. The music controls the emotions in a room full of sound elements, while the guitarist is a. mistake, and there is always something unique about his hypnotic sound.

Fueguia 1833 perfume production

Fueguia 1833’s scents are native to the lands of South America, where founder Julian Bedel lived until he was thirty-five. To him, being able to imagine a poem, a place, a music track, the neck of a vicuña or a painting from the nineteenth century by making a scent about it is akin to creating a soundtrack, or a «scent track», as Bedel defines it. It is a matter of quoting, or being inspired by, the work of Argentinians. The people who built his culture.

Jorge Luis Borges, one of Bedel’s literary references, has had an influence on him since his childhood. Fueguia 1833 honors his work through a series of perfumes belonging to the Literatura collection. El Otro Tigre is one of them. A poem imbued with symbolism, metaphysics, and allusions to scent, the text leaves it up to the reader to recognize its subject.

«It could be a tiger, a cat sitting by the bed, or imagination. In the end, it’s your own tiger». Borges’ oeuvre lends itself to multiple interpretations and to be re-experienced in time. Such details echo the brand’s take on perfume, and its philosophy regarding limited editions, which consider a perfume’s age as an asset and a distinguishing mark.

Fueguia 1883’s guiding principle

The guiding principle behind the development of Fueguia 1833’s four-hundred-bottle batches was the optimization of resources in relation to the scale of their production. As Bedel recounts, there was «a happy accident though» in their evolution. «After one or two years from production, we started to open and smell the bottles we could not sell, and the change in their scent amazed us».

Observing the discrepancy between the smell of a newly-made perfume and that which remains at the end of the bottle, when an essence has had the chance to mature and ethanol rounds out, led Bedel to formalize the discovery into editions. «In 2016 we began putting aside ten to fifteen percent of our production to make vintage editions. We wait five years, then we bottle it and we package it with a vintage label. Customers can experience the difference between new and aged editions in our stores, and they can learn about the meaning of our decision».

Julian Bedel’s childhood

Perfumery, for Julian Bedel, was a calling. Coming from a family of landowners, Bedel experienced the wilderness of the Argentinian landscape from an early age. Nested between the Paraná and the Uruguay rivers, his family owned a two-thousand-hectare property in Entre Ríos. An area where agriculture and hunting traditions coexisted, located in the Mesopotamia region, where animals roamed and native species thrived.

At his family’s estate, Bedel cared for plants and flowers, pruning from dawn to dusk. His job as a laborer in a sub-tropical area influenced his curiosity towards botany. Bedel’s curiosity for these ingredients came from the region’s culture and medicine. His exposure to man-made scents traces back to the smell of pigment and chemicals that reigned at his father’s atelier. An artist and sculptor, it was him who set off his fascination towards the science behind perfume-making.

Bedel was bewitched when he read a scientific paper by Nobel Prize winner Linda Buck that, by taking into account the coding of our genome, expanded upon the ways humans interact with volatile molecules. It became a subject of artistic inquiry to him, and a way to frame a question, akin to sculpting or painting.

The founder’s take on the universe of scent distillation

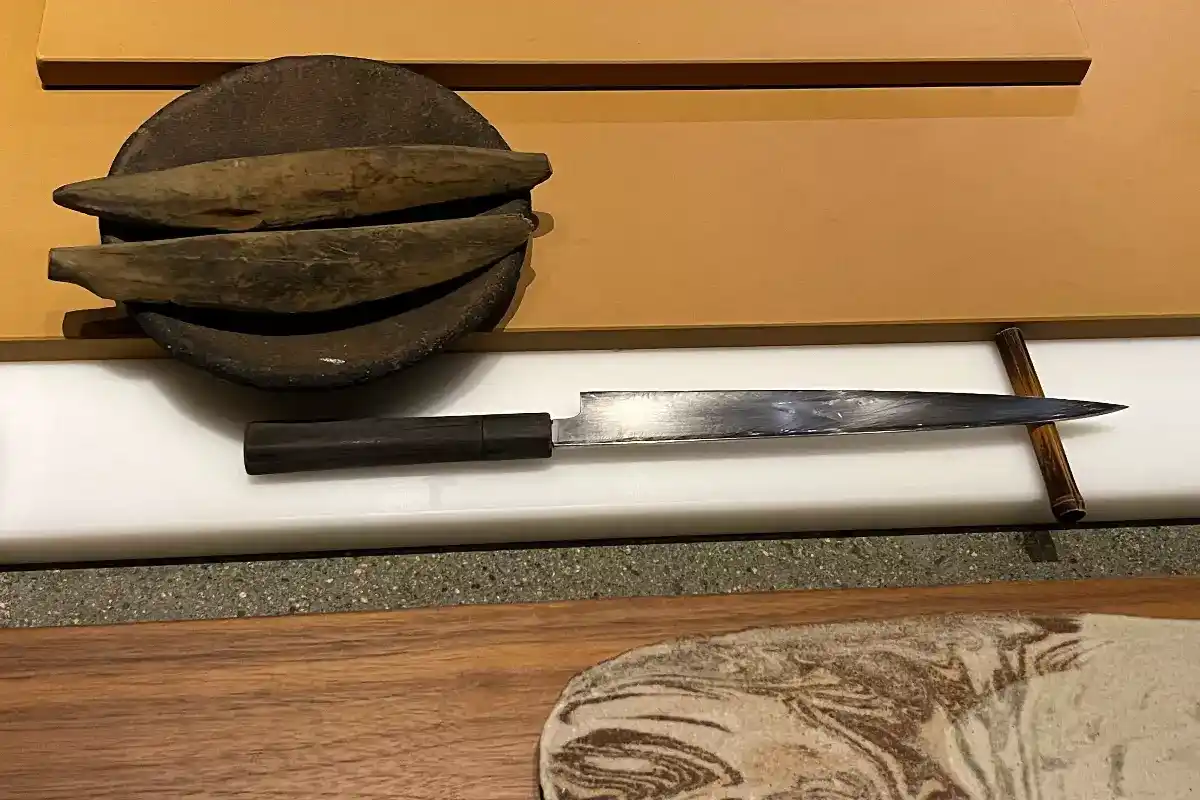

A desire to refine the techniques and methodologies underlying Fueguia 1833’s research and production has since driven Bedel’s take on the universe of scent distillation. At twelve, Bedel started studying lutherie. The art of building string instruments. The impact of his training as a musician on his take on perfumery moves between the sense of smell and that of hearing. To Bedel, in music as in perfume, silence is key. «Silence is a concept one can experiment with. I spoke about this with Yasiin Bey, with whom we collaborated to create a perfume, Negus. In music you have rhythm and an attack, that is the drums».

In perfumery, two key concepts characterize it. Volatility, or molecular weight, and flash point, when liquid turns into vapor. Following these principles allow Bedel to make space for novelty and unexpectedness. «The organization of the script of a formulation creates anticipation. With citric notes, such as hexenol, linalool, beta-Pinene, one can infuse a perfume’s attack with immediacy, speed, confusion and numbness. While with musks, vanillas, woods, one gets a slow release». The overlapping art fields Bedel came into contact with, and the synergies between them, guided him in the development of his approach to perfume-making, which he calls empiric. «Unless you are a genius, you need to establish an empirical relationship with the tools that you use. Be it pigment, wood, or an instrument. It is a learning process».

Bedel’s first steps into the world of perfumery

Through his relationship to the arts, Bedel understood the importance of composition, and knowing when to stop. «In painting there’s a point when you start ruining the initial intent. It is the same in perfume». Bedel’s didn’t have a knowledge of the industry or the market during his first steps into the world of perfumery.

He learnt the basics of formulation, in fact, by studying the composition of woods, oils, roots and flowers. He, then, began reading patterns and finding affinities among volatiles as he progressed. «Working with molecules means not knowing the identity of an ingredient. That’s the stage when semiotics intervene and one starts to understand. Mixing plants is a way to add complexity or an effect to a perfume. It could be excitement, cluelessness, pleasantness».

In terms of process, when a plant or flower is going to be the main character of a perfume, a creator needs to research the volatile molecules that constitute it to elevate its beauty as an ingredient. Wood is an eighty-molecule ingredient. While a flower tends towards one-hundred-and-fifty.

Through fermentation – of elements such as tobacco, cocoa or oud – the molecule count rises to three-hundred. Acquiring an understanding of the plant that needs to be worked with leads to identifying compatibility potentials. Combinations with plants whose molecules or building blocks resemble those of the key ingredient.

The history behind the choice of name Fueguia

Bedel perceives a lack of interest in Argentinian heritage and in the people that inhabited its lands before European colonization. Up until the nineteenth century, in fact, people have erased indigenous peoples of Argentina from history. Between the end of the eighteenth and the start of the nineteenth century, botanists such as Aimé Bonpland, Charles Darwin and Alexander von Humboldt started looking for plants in South America for commercial purposes. The story of scientific explorations, navigation and travel mixes with that of Fueguia Basket.

A native girl from Tierra del Fuego who was abducted, taken to London, capital of the British Empire at the time, and brought back to her motherland, where she was disowned by her family and community. To Bedel it made sense to choose a name that paid homage to Fueguia herself, and to invest in telling that side of history. «Argentina is a country of immigrants. Native communities like the Mapuche live in rural areas, and opportunities for them are scarce. In this sense, Fueguia 1833 is a reflection on who we are».

Bedel’s foundation, Help Argentina

The brand’s vision is a way to celebrate the plants, animals and soil of Argentina, and the genius of those who cared for them throughout the centuries. In 2002, Bedel founded Help Argentina, a foundation that allowed him to coordinate with communities to source and transform materials.

Because of granulometry, the best way to distill a wood is by using its saw dust, which is why Bedel collaborates with locals from Southern Patagonia to collect guaiac wood originating from Bulnesia sarmientoi – a tree endemic to South America’s Gran Chaco region – and with the National University of Patagonia to transform into an essential oil. Help Argentina’s and Fueguia 1833’s social engagement is not based on providing assistance. It is about giving resources to communities so they can participate in production in a way that holds value to them, and supporting the process with tools or funds.

Fueguia Botany: a research and development base

Undertaking the role his family’s farms used to play, Fueguia Botany is located in Uruguay, five kilometers away from the coast. The ten-hectares plantation hosts a variety of plants originating from South America. These include citrus, vetiver, iris, marcela, acacia, together with invasive and medicinal plants. There, Bedel started to look into flower and plant fermentation.

The Botany now acts as a research and development base, where the team can experiment with extraction methods and ingredient production. In 2015, Fueguia 1833’s plant and manufacturing moved to Moncalieri, Italy, together with Bedel himself. Today the entirety of Fueguia 1833’s productive chain is based in Milan, where the brand owns a one-thousand-square meter facility and a five-hundred-square meter woodworking site dedicated to the production of furniture, display elements and packaging.

Quality control, the study of allergens and pesticides, formulation, extraction and purification occur in the perfume laboratory in Milan. It is where Fueguia 1833’s creations come to life. In the factory, in fact, perfume mixes with ethanol and moisturizers, undergoing a process of retting, maturation and filtration that ends with bottle engraving, filling, closing and wrapping.

A process freezing ethanol at -80°C

In March 2021, the brand spent two-and-a-half million euros in equipment for its R&D department, taking advantage of current incentives, which promote a shift to industrial automation. «We invest in gas chromatography, mass spectrometry and HPLC (High Performance Liquid Chromatography). During the fermentation of ingredients, when we look for boswellic acids – deriving from the resin of Boswellia sacra, Boswellia frereana and Boswellia serrata – these technologies allow us to quantify them and control their development in time. They enable us to identify the content of terpenes in the materials we purchase. The amount of vetiverol in vetiver, patchoulol in patchouli, of allergens and pesticides».

Speaking of R&D, Fueguia 1833’s team is developing a process that involves freezing ethanol at -80°C. As Bedel explains, «at this temperature, ethanol becomes selective in molecule extraction, avoiding chlorophyll and waxes. This is a way to achieve powerful ethanol extractions, to recycle ethanol, and to employ leftover waxes in our candles». A further technology Fueguia 1833 has been investing in is supercritical fluid CO2 extraction. It allows them, in fact, to see peaks and concentrations in a plant’s molecules. These kinds of investments do not generate a monetary return. But they allow the brand’s research department to experiment, while extending its capabilities and expertise.

Fueguia 1833’s commitment to sustainability

«I don’t create formulas through ingredients. I write down a formula in an Excel sheet, or on paper, and I go to the lab to tweak it and balance it. Then I send this to a machine that, through automation, elaborates the one-hundred-and-fifty ingredients required to make a perfume. This allows me to save time and to avoid exposure to solvents. It also reduces the amount of labor required».

Fueguia 1833 is now creating the first perfume made from olive leaves, working with fermentation and concentration to refine the scent and highlight the material’s olfactory profile. In the cosmetic industry, professionals extracts squalene using olive leaves. In the production of olive oil, they are burnt or given to animals.

«Sustainability is about finding imperfections and transforming them into something that can be used. A sustainable approach guarantees efficiency. It’s not about owning credentials or certifications. We consider what can have impact in our production chain».

Sustainability, a business principle based on effectiveness

Fueguia 1833’s perfume boxes and the interiors of the brand’s boutique in Milan feature wood scraps as well as leftovers from fallen trees of European spruce, or Picea abies. This is used as a source of tonewood in the making of string instruments. Wind energy powers the brand’s factories – a cost-effective choice. «I don’t see sustainability as an effort. On the contrary, evidence shows us that it is beneficial to the economy».

To Bedel, sustainability is a business principle based on effectiveness. Fueguia 1833 held this as a paradigm since its birth, together with biodegradability. After distillation, at Fueguia 1833’s plant, the remains of the ingredients’ biomass undergo an additional distillation process, as they are replete with acids employed in skincare and pharmaceuticals, the by-product of which is made into incense. The brand forgoes the use of plastics in its products, except for the pump, which they aim to substitute with a glass one, and a card insert in the packaging made of bioplastics.

Lampoon’s review: Fueguia 1833’s future perspective on the perfumery industry

«We haven’t been trained to see what’s behind a perfume, or what its production entails. The owners of the perfume industry look for profit. If their customer does not ask, they can give them what they have at hand. On the customer’s side there is a lack of responsibility. But the moment people stop buying, the paradigm changes». Nowadays the industry is getting the message, but it is acting slowly and charging more to guarantee its adherence to sustainability.

As Bedel notes, the industry should lower the cost of ingredients with a limited impact – not inflate it. The perfume industry doesn’t only include the world of luxury perfumery. It is also the industry that produces deodorants and home perfumes. Examining the industry as a whole, the sourcing of materials, traceability, workers’ conditions and pay, and the sustainability of process – in terms of energy consumption and crops renovation – are an issue.

Water contamination is among the ways perfume manufacturers have an impact on the environment. It is the scarcity of environmental laws in countries such as China and India, where production costs are lower, that allows brand owners to pollute without incurring in penalties.

Ignorance is the root of the problem

Today, ninety-nine percent of perfumes contains polycyclic musks. Brands still advertise the presence of cashmeran in their products. This is a polycyclic musk. A compound found in human milk in the nineties, which is a hormone disruptor. «Alternatives are available. But until there are no laws forbidding the use of certain ingredients, brands will keep operating as they have for decades. Shifting to sustainable options implies that a product will smell different and that it will be more expensive. An aspect nobody is willing to comply with».

From the customer’s point of view, the promises made by niche brands – of artisan production or natural ingredients – may seem to justify the price increase. Bedel argues that hypocrisy marks these kinds of statements. «It may be that they have never heard of polycyclic musk compounds, or they are not interested, or they stop paying attention when they realize they would have to pay more».

To Fueguia 1833’s founder, the root of the problem is ignorance. Brand owners, in fact, are selling products without knowing their ingredients or the environmental implications of their production cycle. «It’s frustrating that, despite the knowledge we have at hand, the industry keeps moving in the same way. We are not a perfect brand, in sustainability or in any other way, and I don’t see myself as an activist. The fact of producing in itself is not positive. We, therefore, acknowledge these problems in every perfume we create, and we work on finding ways to improve. Enacting change takes time. This industry has been making perfumes for more than a hundred years. But communication channels can help speed up the process, and push people to do better».

Fueguia 1883

Fueguia’s boutiques are currently located in Milan, New York (Madison and Soho), Tokyo (Roppongi and Ginza), London (Harrods), Buenos Aires and Jose Ignacio (Uruguay). Fueguia products are also available through a network of selected distribution partners