Balkan Aesthetics: the last frontier of authenticity?

From contemporary art and social media to bunker bars and stucco columns, Balkan aesthetics offer an antidote to globalized smoothness: Alterazioni Video’s Olbania and Šejla Kamerić’s Bosnian Girl

Balkan roughness and the Europeans: not a constructed aesthetic

Balkan roughness is as uncomfortable and ridiculous to Europeans as it is captivating. It is an aesthetic without intermediaries, rooted in sincerity and born in streets and kitchens, in unlicensed taxis, suburban karaoke bars, and improvised nightclubs. Every non-symbolic object is purely functional: electrical cables blanket major boulevards and obscure Roman ruins; exposed air conditioners scar façades; beer bottles decorate sidewalk corners; cigarette packs rest in makeshift holders on tombstones. At the same time, everything with communicative intent sheds functional restraint: oversized car spoilers, Greek pediments grafted onto industrial warehouses, massive, mirrored sunglasses seemingly welded to faces. The urge to appear is so strong and unconditional that appearance itself becomes reality.

This kind of spontaneity is foreign to Europeans, despite geographic proximity. That is precisely why outsiders feel its magnetic pull: everything appears simultaneously absurd and true. It is easy to mock, yet deeply captivating in a way that feels unsettling, as if one were not quite permitted to admire certain crude but undeniably brilliant inventions, or the indulgent use of classical symbols and phosphorescent colors—often side by side. Arthur Danto’s reading of Jeff Koons comes to mind when, quoting Wittgenstein on philosophy, he writes that “these objects appeal to anyone who has not been corrupted by great art.”

This is not a constructed aesthetic. It is what remains when everyday life steamrolls theory, style, and the impositions of “good taste” and abstract values. Spontaneity outweighs intention; kitsch coexists with devotion, trash with history, architectural grotesquery with natural beauty, the desire for visibility with a lack of awareness of aesthetic impact. For these reasons, in a world saturated with polished images, the Balkans have become one of the last reserves of aesthetic authenticity. Here, every image is an excess—an exaggeration, a mistake that hardens into style.

Alterazioni Video’s Olbania: 600 images from Albanian social media as aesthetic, linguistic and cultural re-signification

“From the very beginning, this has been Alterazioni Video’s gesture: a radical act of symbolic re-signification, aesthetically, linguistically, and culturally. We looked at what everyone called failure and said: it’s a style,” the collective writes in Incompiuto. The Birth of a Style (Humboldt Books, 2025). The book presents their best-known project: a catalog of unfinished public works across Italy, reframed as an architectural manifesto.

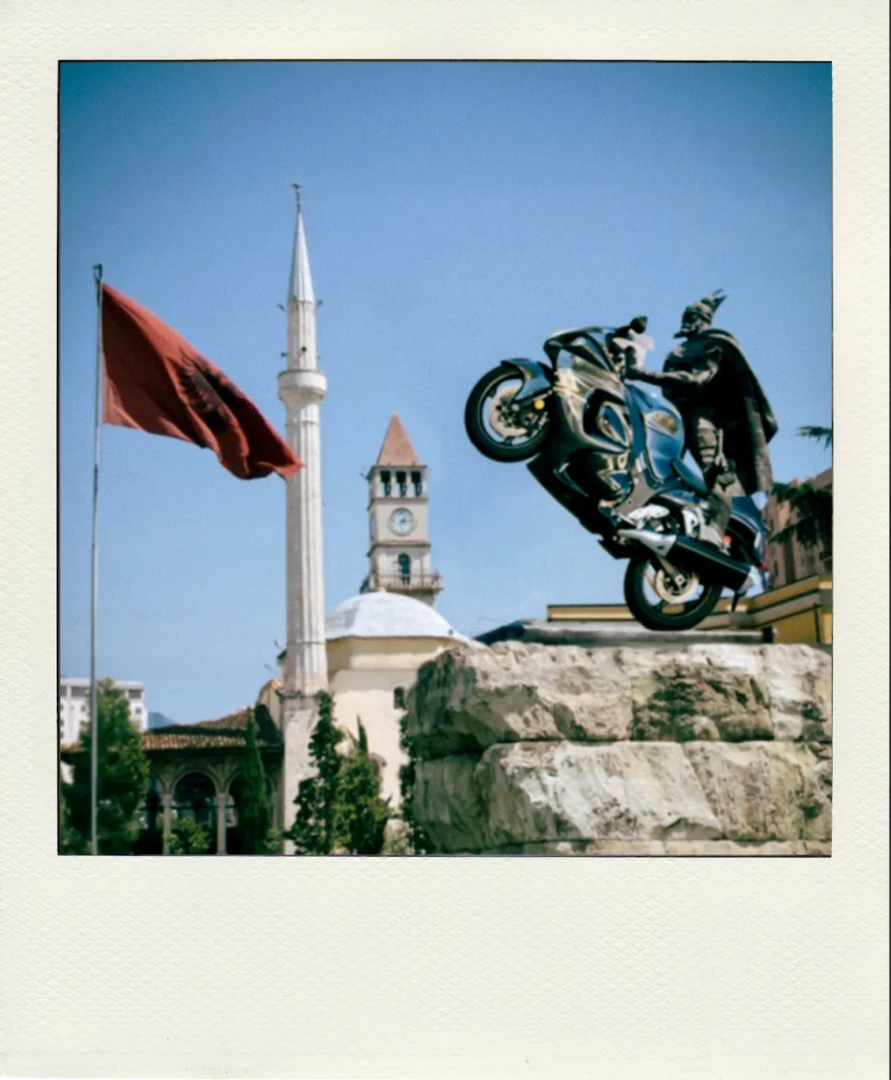

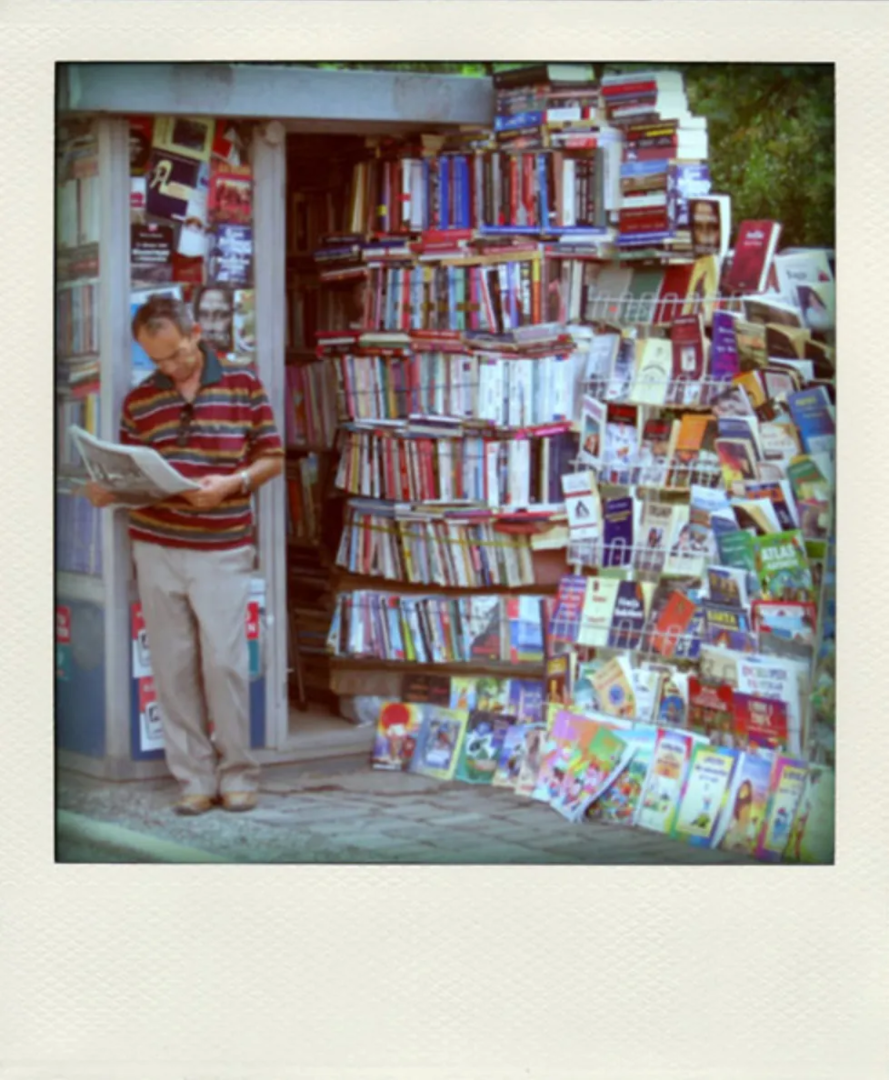

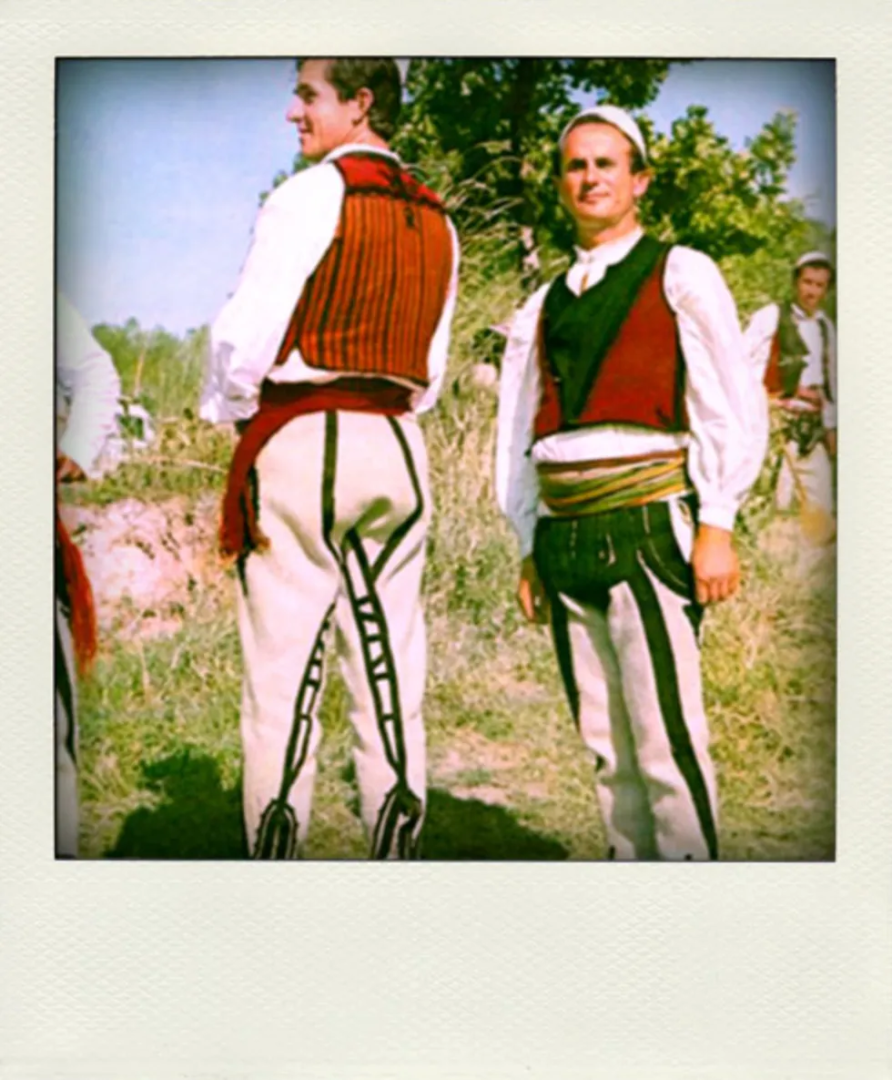

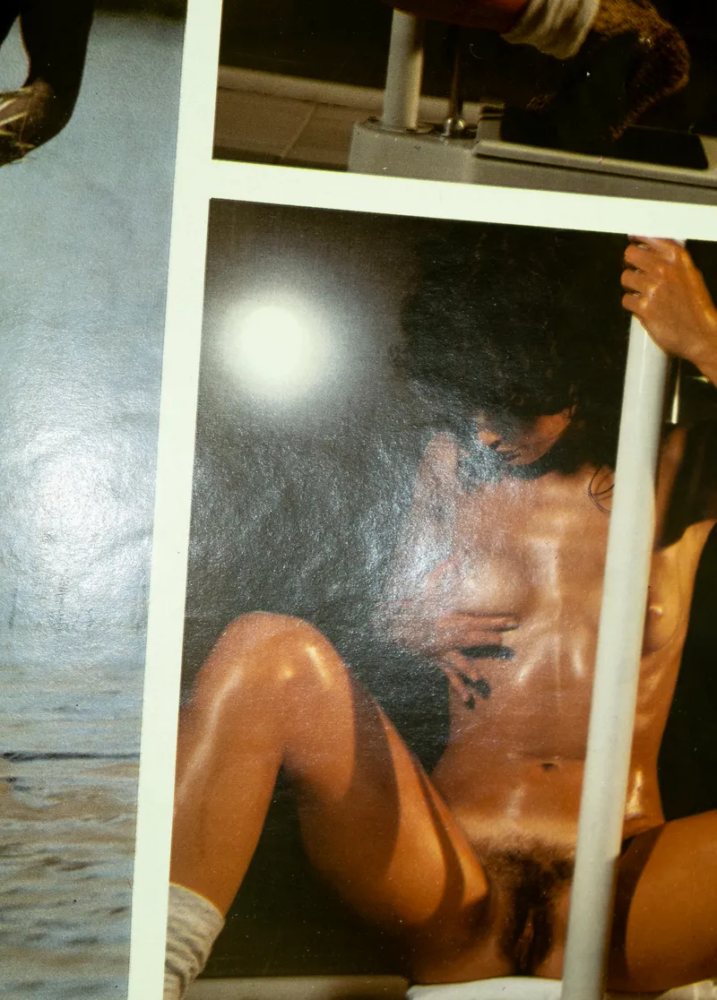

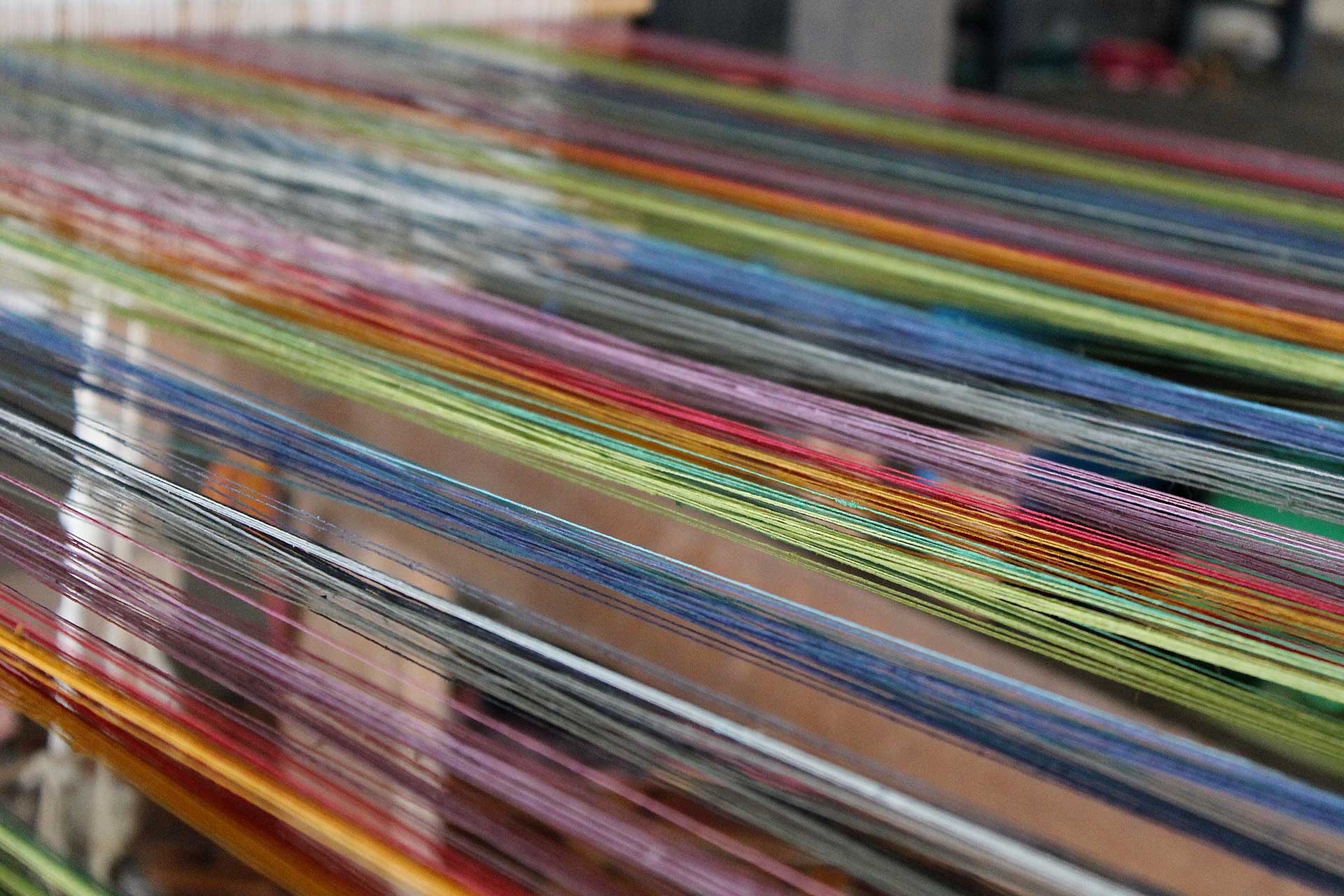

This method—seizing upon a preexisting, overlooked phenomenon and shifting public perception through the re-signification processes typical of modern and contemporary art—was also applied to Balkan aesthetics in Olbania. The project brings together more than 600 images sourced from Albanian social media, alongside photographs taken by the artists themselves, processed to achieve an analog, aged look and printed as Polaroids.

An ironic and irreverent portrait of a country, light in tone yet resonant over time

The result is an ironic and irreverent portrait of a country seen through the eyes of its own inhabitants, engaging—often for the first time—with a medium that allowed them to communicate with the rest of the world. Despite its playful, almost childish humor, the project rests on solid artistic foundations and reveals considerable ambition, even if concealed beneath Alterazioni Video’s signature nonchalance and feigned naïveté. It is a work that feels light while carrying lasting weight, as evidenced by its ability to remain contemporary more than fifteen years after its inception, despite relying on inherently ephemeral media.

Currently on view through February 23 at the Marubi National Museum of Photography in Shkodër, Albania, Olbania was originally conceived in 2009 for the third Tirana Biennale and completed in 2011 for Zeta Gallery in Tirana. It was later exhibited at Fabbrica del Vapore in Milan and at 319 Scholes in Brooklyn in 2012.

The title Olbania comes from a common misspelling of “Albania” that circulated in the early 2000s on MSN and other online forums. In a similar spirit, the collective itself—founded in Milan in 2004 by Paololuca Barbieri Marchi, Alberto Caffarelli, Matteo Erenbourg, Andrea Masu, and Giacomo Porfiri—borrowed its name from a grammatical error found in a television set instruction manual. As Sara Dolfi Agostini, curator of the Shkodër exhibition, notes, “Alterazioni Video like mistakes.”

This is precisely why the Balkans provide the ideal setting for the group’s loud, exaggerated, and provocative practice, marked by bad taste, cheap yet flamboyant aesthetics, and crude but ingenious ideas. It also explains their prolonged flirtation—or full immersion—in Balkan culture, embraced as an unruly, ridiculous, and sincere alternative to the flat, overpolished, and sterile sameness of globalized society, a sameness that increasingly permeates the visual arts.

Car washes, record-breaking meatballs, and migrants: Alterazioni Video’s Balkan works

Alongside Olbania, Alterazioni Video presented the performance Lavazh Parti in Tirana in 2011. The work invited citizens to gather and wash their cars—a core ritual of local culture, as any visitor to the region will quickly notice from the sheer density of car washes and gleaming vehicles. The event was promoted with a radio announcement and a poster that looked as though it had been made in MS Paint, complete with the slogan “for an Albania as clean as my car,” which lent a sharp political edge to an otherwise ludicrous premise.

Earlier still, in Ljubljana, Slovenia, the collective staged Veliki Ćevapčić (2008), a performance in which Alterazioni Video secured the Guinness World Record (the first of the nine they now hold) for the largest meatball ever made, later offered to the entire city to eat—again accompanied by a radio announcement. Beyond designing the metal apparatus required to cook the 630-kilogram meatball, the group organized a full-scale event featuring, as the press release put it, “a live band playing Turbo Folk music, two go-go dancers dancing on stage, and free beer for people.” The same text described the meatball as “a horizontal obelisk to honor those who throw monuments down, redistributing power and wealth. […] A temporary monument and a folk happening that raises questions about nationalism.”

Another example is the photograph Crusing from Albania (2010) [sic], which depicts a tanned man in mirrored sunglasses and a tank top emblazoned with the Albanian flag, floating on a cluster of beach inflatables. The image riffs, with bitter irony, on the tragic mass exodus of the 1990s from Albania to Italy.

From pyramid-scheme riots to mass migration: Olbania engages with Albania’s history and its digital transition

Albania’s history is turbulent and deeply entangled with that of Alterazioni Video’s own country—from Mussolini’s invasion to the mass migration that followed the fall of the Communist regime, culminating in the arrival of the cargo ship Vlora in Bari in 1991, with more than 20,000 Albanian migrants crammed onto its deck. The collective is fully aware of this history and deeply invested in it.

It is no coincidence that Olbania captures the moment when a nation long isolated from a geographically close West moves from limited, mediated contact to full global exposure—from relying on Italian radio and television to accessing the World Wide Web. (Instagram reached Albania in 2010, one year before Olbania was created.) And, as with Nietzsche’s abyss, when you gaze into the web, it gazes back. Between 2009 and 2010, the internet began to fill with images of everyday Balkan life taken not by reporters or artists, but by Balkan people themselves: proudly displaying their goats and modified Mercedes, freshly caught fish and improvised barbecues, eclectic architecture and questionable outfits, bunkers repurposed in eccentric ways, and, inevitably, the ubiquitous red-and-black flag.

Celebrating stereotypes: reflection and appreciation through an outsider’s lens

There is no doubt that Alterazioni Video play with Balkan stereotypes—folk mythologies, gaudiness, patriotism—but they do so without judgment or condescension. Instead, they give these elements form and force. As Dolfi Agostini explains, “Olbania should be seen as neither a parody nor a critique of Albania,” but rather as a celebration. Through irony and clarity, the project offers a platform to a culture to which the artists are self-aware outsiders, yet one that irresistibly attracts them—as it attracts many of us.

Crucially, their approach also involves the people portrayed, who may find both amusement and self-reflection in encountering these representations. Writing in 2011 on AlbaniaNews after seeing Olbania at Zeta Gallery in Tirana, Alma Mile observed: “They described and observed everyday reality by taking advantage of the fact that they are not from here. […] As you look at photo after photo, you ask yourself: do I really live in such a bizarre country?! Or should we ask instead: do we really look this strange to foreigners?!”

Alterazioni Video meets Richard Prince: appropriation art and the smoking cowboys

The strength of Alterazioni Video lies in the fact that while one foot is planted in the irreverence and chaos typical of digital cultures (and of the Balkans), the other is firmly grounded in the more elusive territory of contemporary art. The group knows this terrain intimately and deploys it strategically, giving each project a solid conceptual framework that ensures durability and resonance.

It is no coincidence that the cover image of Olbania features a Polaroid of a billboard depicting a dramatically smoking cowboy, beneath which stands a far less romantic figure: a hatless man with a cart of firewood and a frail horse. Anyone even vaguely familiar with contemporary art will recognize the trope of advertising photographs of smoking cowboys. The very first of the 600 photographs on display appears to reference Richard Prince, arguably the most influential appropriation artist—and prankster—of recent art history. This is hardly accidental, especially considering that Prince himself would later produce a body of work sourced from social media, his infamous Instagram Paintings, three years after Olbania.

Šejla Kamerić’s Bosnian Girl and the Katër i Radës tragedy: art as memory and resistance

Dolfi Agostini notes in the press release for Olbania that “most of the images cannot be found or tracked on the internet today.” Indeed, the original version of the cover image can no longer be traced; we will never know whether its author was aware of Richard Prince’s cowboys. A reverse image search, however, reveals another photograph that appears to show the same billboard: a stock image available on Getty Images, taken by Bernard Bisson on February 3, 1997. In this version, a donkey-drawn cart carrying what seem to be three stern-looking boys passes beneath the smoker. The image is titled Tirana the day after the demonstrations by the ruined investors, referring to the 1997 nationwide riots triggered by the collapse of government-backed pyramid schemes, in which more than 2,000 Albanians lost their lives.

Just one month later came the sinking of the Katër i Radës, an Albanian vessel rammed by an Italian Navy corvette as it attempted to reach the coast of Otranto, killing 81 migrants. If Alterazioni Video respond to this tragic past with a deliberately external and stereotyped gaze—as in Crusing from Albania—a very different approach can be found in the work of Balkan artists who experienced the consequences of those tragedies firsthand.

Balkan sincerity is not only irony or disorder; it is also wound. This is powerfully demonstrated in Bosnian Girl (2003) by Šejla Kamerić. The work superimposes the artist’s face onto an insult written by an unknown member of the Royal Netherlands Army during the Bosnian conflict. It uses the same visual immediacy found in everyday kitsch, but anchors it in trauma. Distributed as posters, billboards, magazine ads, and postcards, the piece forces viewers to internalize the racist graffiti: “No teeth…? A mustache…? Smell like shit…? Bosnian Girl!”

Celebration and critique: two ways of appropriating reality without polishing it

Alterazioni Video appropriate stereotypical Balkan imagery and celebrate it; Šejla Kamerić appropriates material produced to demean and turns its violence back on itself. Bosnian Girl and Olbania, though radically different, share a core principle: reality must not be polished, but transformed into meaning. Both works rest on the conviction that if art is to confront dominant aesthetic regimes, speak to a broad public, and affect real phenomena, it must abandon sterile notions of authorship and immerse itself in the contemporary image ecosystem—a murky space where distinctions between high and low culture, good and bad taste, no longer apply.

The power of Balkan roughness is contagious precisely because it destabilizes our idea of aesthetics. Its existence demonstrates that excess is not a flaw, kitsch is not shameful, and spontaneity can outperform formal coherence. In a Europe that produces standardized images—where every city begins to resemble the previous one and every social feed endlessly repeats the same poses—the Balkans function as a visual short circuit. Yet even this reserve is becoming increasingly fragile. One need only look at how the influx of new capital into Tirana has transformed Skanderbeg Square into something closer to a Scandinavian plaza than an Albanian one; in this process of homogenization, it is the inhabitants themselves who seem increasingly out of place.

Against global smoothness: preserving the sincerity of Balkan aesthetics

This is precisely why a project like Olbania remains necessary. It renders Balkan aesthetics into a coherent and enduring style. It should be understood as an act of attention—and even affection—toward the marginal and the strange; an attempt to capture and preserve, not as a specimen in a vitrine but as a living, unstable organism, a feverish and captivating ecosystem threatened by homogenization.

Alterazioni Video and Šejla Kamerić show that this way of appearing, having become a way of living, can be transformed into language, critique, memory, and even hope. As Alterazioni Video write in Incompiuto: “Art must embrace its ambivalent status: it no longer represents the world, but constructs it. And it builds it through images, gestures, and symbolic devices.” For this reason, it is essential to deploy the easy humor of funny images and stereotypes—together with the tools and languages of art—to celebrate difference, preserve cultural memory, and inject a new aesthetic vocabulary into the increasingly stale field of contemporary art.

“We observed the everyday as if it were a ritual, decay as a symbolic form. We turned investigation into a poetic gaze. And the useless into a critical object.” Balkan uselessness, then, becomes an antidote to global smoothness—an invitation to reintroduce the unpredictable, the strange, and the alive into our way of seeing. And perhaps this is why it fascinates us so deeply: because it reminds us that images, to truly mean something, must first and foremost—at any cost—be sincere.

Luca Avigo