Definition of Sustainability: Fashion Without Microplastics

It has become a common refrain—among buyers as well as certain managers—to say that sustainability doesn’t sell, when in fact sustainability simply isn’t on offer. The entire fashion industry is built on synthetic materials

Sustainability Doesn’t Sell; Customers Don’t Care

Buyers and Boomers are convinced: “sustainability doesn’t sell.” Buyers who, by virtue of their generation, were already professionals in the Nineties insist that customers just aren’t interested. They say: everyone talks about sustainability, but when it comes time to purchase, consumers don’t buy it. They repeat: customers don’t care about sustainable offerings.

This was explained to me during a meeting with a buyer who has years of experience and now heads a concept store located in both Italy and Korea. I try asking: what sustainability options are on the shelves and racks? What is actually available in the store that could be considered sustainable? Is there anything sustainable for sale that people might want to buy? Perhaps the truth isn’t that consumers don’t care—maybe there’s simply nothing sustainable being offered.

No Offer, No Sustainability in the Product

From big brands to up-and-coming designers, whenever they talk about sustainability, they discuss recycled fibers, regenerated plastic, supply-chain support, and diversity and inclusion in the workforce. They speak of sustainability by highlighting waste reduction, a move away from fossil-fuel-based energy, or the implementation of progressive corporate welfare. All of that is great, of course—worthy of admiration and a nod to progress. They never get around to examining the product itself. What rolls out of the warehouses is still made of nylon and polyester.

Nobody talks about genuine, concrete, pragmatic sustainability in the product that actually goes on sale—even though clear, straightforward messaging is needed to break down the barriers. Here’s the definition: for a textile product to be sustainable, it must not release microplastics. That’s all—simple as it is.

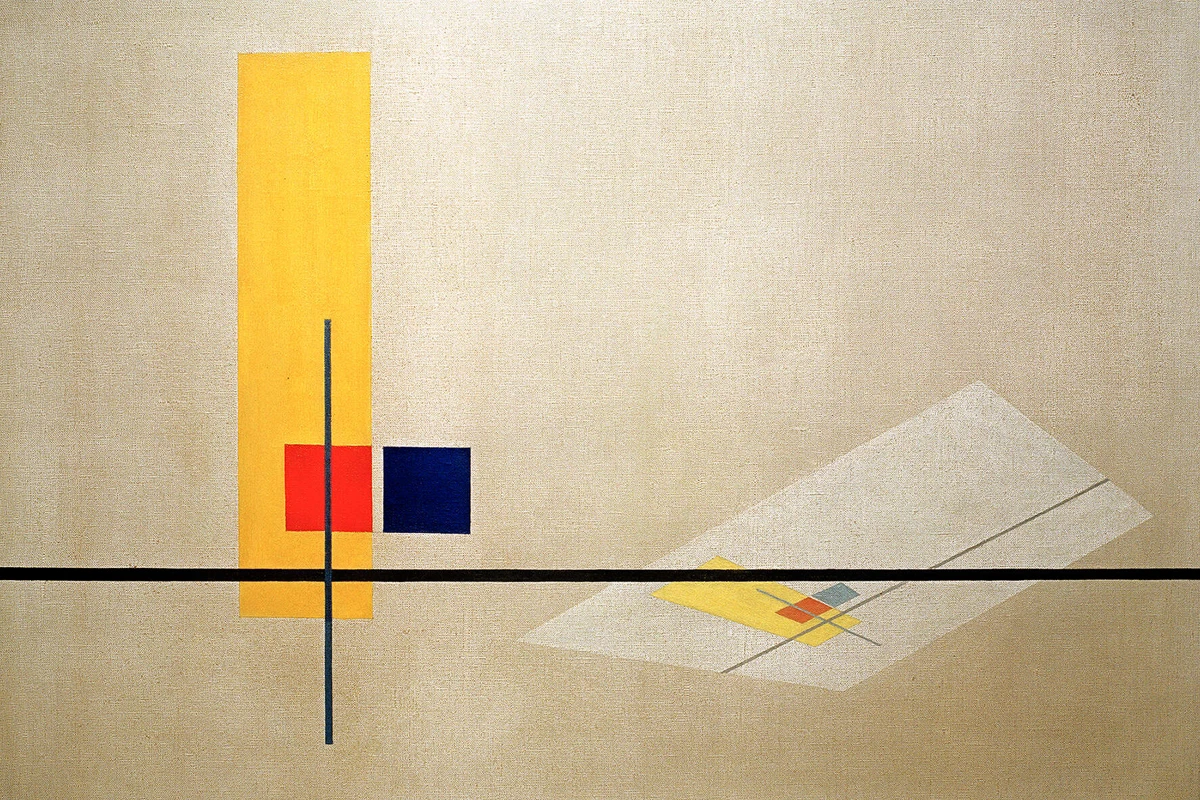

In the concept store mentioned above, you’ll find ultra-cool pieces: graphic designs, bold statements. Everything is black, stretchy, padded, or in leather. Plastic sequins, phosphorescent prints. This is what’s on display in one of Milan’s trendiest concept stores. And yes, Rick Owens, Duran Lantink, Alaïa—they’re all super stylish. I italicize these terms to convey the slightly ridiculous impression they can create. My friend, a woman I’ve always adored, has launched a new brand of neon-printed stretch bodysuits—and I don’t see the point.

Definition of Sustainability: A Textile Product Must Not Release Microplastics

I’ll say it again: a textile product must not release microplastics if it’s sustainable. In other words, it must not be made of synthetic fibers, glues, or dyes fixed with acrylic substances that break down into micro-particles and disperse when washed. If these synthetic fibers are recycled, they may fragment even more easily. If nylon is regenerated—meaning the material is melted down and re-extruded into thread—the resulting fiber is solid. If a nylon textile is opened and shredded in order to produce shorter fibers to be re-spun, the final fabric is even less stable and more prone to tearing. A fabric must not release microplastics: that is the only definition of sustainability in textiles. This type of product doesn’t exist on shelves; if it isn’t there, nobody can buy it. Sustainability doesn’t sell because sustainability isn’t available.

In manufacturing and production, creativity continues to rely on synthetic fibers and polyurethane filling in elastic fabrics, nylon, fluorescent prints, and deep black dyes. It seems that, to express itself, creativity can’t do without all of that. There’s little interest in developing innovations in natural fibers or dyes, single-material solutions, or new approaches to cutting, sewing, or knitwear that could produce groundbreaking results. On the shelves, you’ll find black leather pieces dyed so thoroughly that liters of water have been used for just that one shade.

Leather: By-Product of the Food Industry, Diet, and Red Meat

Leather is a by-product of the food chain. If it weren’t used by the fashion industry, the hides of all the animals slaughtered for meat production would go to waste. We’re in Italy, where Tuscany alone processes 25% of the world’s leather. Italy’s tanning industry, with its Tuscan hub, works with such a vast quantity of raw hides that it has to import over 90% from abroad.

The food industry sits upstream from the tanning industry. We need to reduce our consumption of red meat—both for our health, as red meat is known to be carcinogenic, and for the environment, since intensive livestock farming is one of the major contributors to systemic pollution. In every supermarket, meters upon meters of shelf space display excessive quantities of red meat—the ultimate symbol of consumerism, the kind that has no conscience. There’s no debate: we must cut back on red meat in our diets.

Leather used for clothing is a by-product of this food supply chain—one of the worst offenders in our hyper-consumerist world. We can’t really call leather sustainable. Or rather, we could if it were possible to prove that it came from extensive livestock farming—that is, an animal raised in open fields. In the industrial system, this is impossible, even at the luxury level.

A Message for the Luxury Sector: Traceability and Suppliers

Or maybe not—perhaps for the luxury sector, it isn’t impossible after all. At least, it needn’t be. In fashion, at the very least, it could be promoted as a message. After all, the fashion industry communicates primarily through a runway show: a spectacular presentation where an attitude, a vision, is staged. Of what we see on the runway, most eventually goes into industrial production, but not everything. The designer focuses on the concept, sometimes without even thinking about how it will be produced. The task then falls to their team to figure out how to make it happen—by talking with suppliers, searching for new ones, and supporting them in innovation. This is a phase of research and creative risk-taking: budget is not the main consideration. Textile suppliers know that a fashion studio might spend hundreds of euros per meter of fabric for a runway piece, postponing discussions about cost until later, when they’ll have to set a reasonable retail outlay.

Runway shows should be manifesto events—a statement of purpose, a loud message. In theory, this is already the idea, but most of the time recently, they are just commercial displays. Major fashion houses could send down the runway a single daring garment that’s fully sustainable—just one piece out of sixty or more—made from leather whose source is traceable all the way back to the farm where the cow was raised, confirming it was open-range, well cared for. It may sound utopian, maybe even make us smile, but it would be a clear, simple, and honest message that many—perhaps everyone—would understand. Even a limited series of numbered pieces—maybe just for the sake of marketing—could show the way forward.

Italian Natural Hemp

Major fashion houses could also produce a few garments using hemp that’s grown, harvested, and processed in Italy—another example. Italian-grown natural hemp can’t be industrially produced at scale right now, but it would serve as a statement. As of today, there is no such thing as an Italian hemp supply—despite the fact that, in the previous century, Italy was a world leader in hemp production. Designers could at least showcase a few flagship pieces, perhaps unfeasible for mass production right now, but illuminating a path for the future. After all, we often hear about unique, expensive items costing tens of thousands of euros, sometimes referred to as couture.

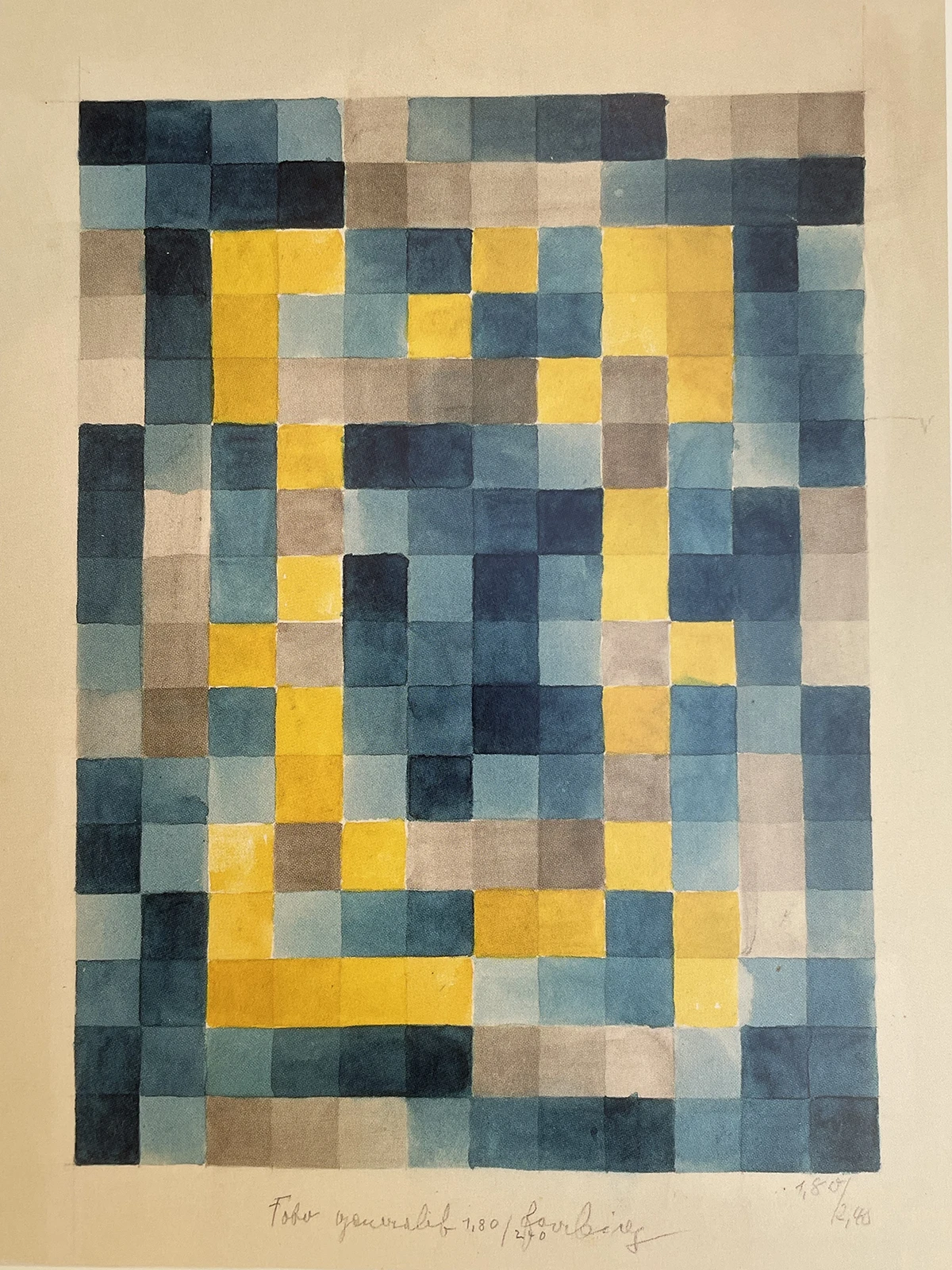

Natural dyes, broom fiber, nettle fiber—and again, hemp—remain virtually unknown, partly because nobody in Europe spins them anymore without resorting to chemicals. Yet hemp is the only textile fiber that can rightly be called sustainable: the only natural, plant-based fiber that can be grown in Italy. In the early 2000s, Giorgio Armani funded a hemp supply-chain project—remembered as “Baby Hemp”—based on a prediction that, in hindsight, defied common sense. Armani’s intention was honorable, but the people who convinced him to do it weren’t well prepared. Something similar happened at Ferragamo a few years later. Last year, Fendi—on a small scale—managed to produce five Baguette bags in natural, Italian-grown hemp. They’re just the first steps on a new path.