Carly Scott SOAP, automatic purity: a car wash is about your life

The first car wash was born from the belief that purity could be engineered – for Lampoon / SOAP, Carly Scott turns the industrial car wash into a confessional of desire

From Detroit to Desire: the first car wash opened its doors in Detroit in 1914

When the first car wash opened its doors in Detroit in 1914, it didn’t look like much: a dimly lit garage, a few metal pails, and two brothers — Frank and J.W. McCormick — pushing cars down a narrow track, one after another. They called it the Automated Laundry. The name hinted at innovation, but the process was entirely manual. Each worker scrubbed, rinsed, and dried by hand while the car was guided through a sequence of stations.

Yet that small enterprise marked the beginning of something larger than either brother could have imagined. The car wash wasn’t just a business; it was a reflection of a new century’s values — a century obsessed with machines, speed, and the promise of renewal.

Carly Scott’s ‘Soap’ vision: where cleanliness becomes a mirror for the self

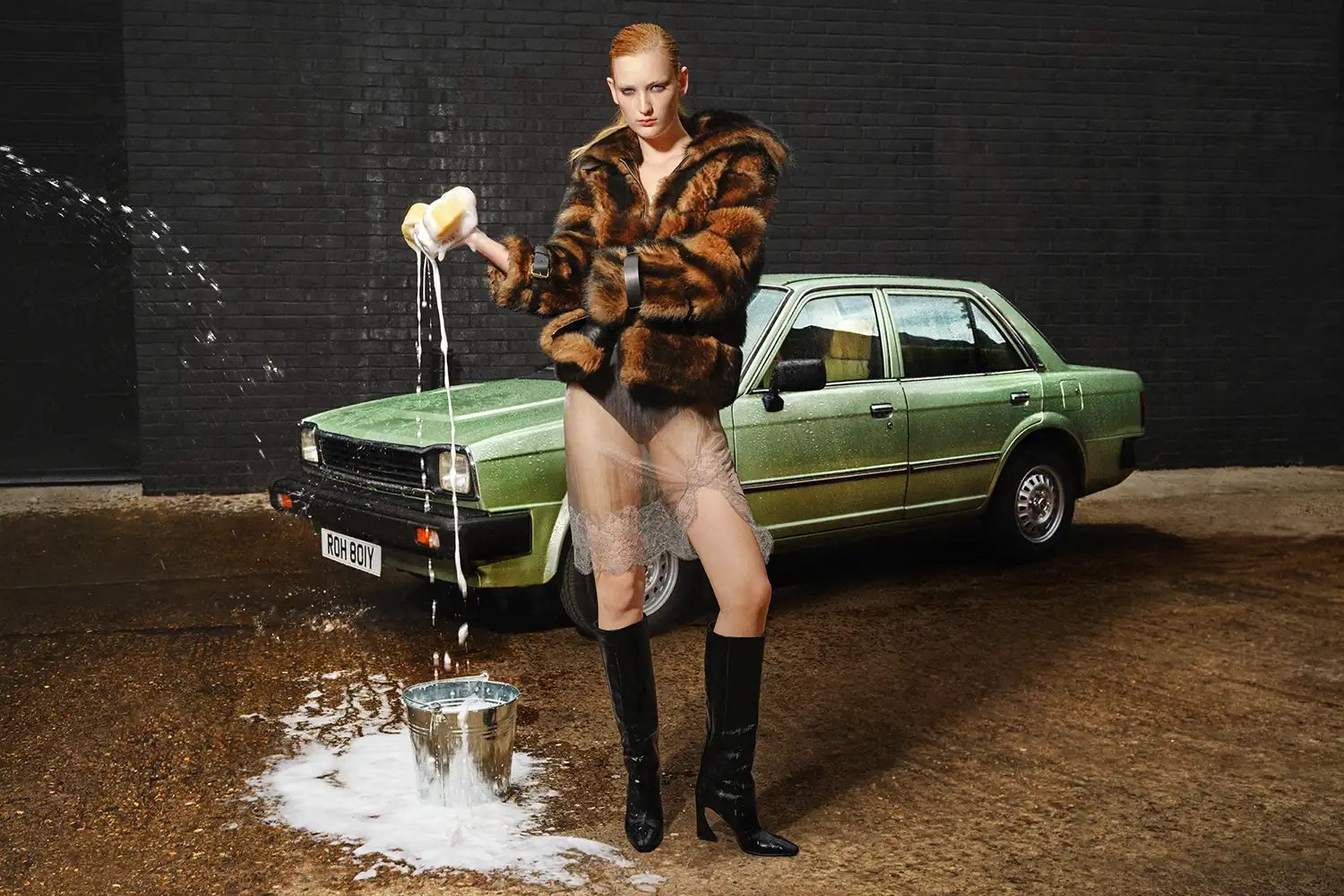

It is precisely this ambiguity that Carly Scott explores in her photographic series for Lampoon Magazine’s SOAP Issue. The London-based photographer — known for her work in Dazed, i-D, Vogue Scandinavia, Twin, Puss Puss, and The Guardian, and for collaborations with Gucci, Vivienne Westwood, Selfridges, and Pleasing — reimagines the car wash not as a site of renewal, but of tension.

In Scott’s images, the industrial setting is stripped of its purpose and turned into a psychological landscape. Models recline on cracked vinyl seats or stand in shallow puddles, framed by rubber tires and blackened walls. Soap suds cling to their legs, half-washed, half-stained. The act of cleaning becomes performative — a struggle between exposure and concealment.

Her series dismantles the binary of “clean” and “dirty.” Instead, it reveals them as mutually dependent states, each giving meaning to the other. Soap, the supposed agent of purity, becomes a reminder of our own residue: the parts of ourselves that can’t be scrubbed away.

The gospel of efficiency: when Detroit turned cleanliness into a machine

Detroit in 1914 was already humming with the rhythm of Henry Ford’s assembly lines. The idea of efficiency — of breaking complex labor into mechanical steps — had become the philosophy of modern life. The McCormicks’ car wash simply extended that logic from production to purification: a mechanized ritual for keeping the symbols of progress immaculate.

Cars, like people, were expected to shine. Dust was disorder; grease was guilt. Cleanliness, in the industrial imagination, stood for control, productivity, and moral order. To wash a car was to reaffirm the faith in technology itself — the idea that anything could be made new again through process and precision.

The early car wash was, in a way, a secular baptism for the automobile: an immersion in water and soap that restored it to its ideal form. The ritual satisfied both a practical and a psychological need. It kept machines running smoothly, but it also soothed the modern conscience — that deep anxiety about the dirt that progress always leaves behind.

When water met the assembly line: how automation made cleanliness spectacle

By the 1930s, the car wash had evolved into a semi-automated operation. Pumps, sprayers, and conveyor belts entered the scene, though humans still played the starring role. It was messy, loud, and physical work. But in 1946, an inventor named Thomas Simpson revolutionized the process with the first fully automatic car wash — a conveyor system that could scrub, rinse, and dry without human hands.

This innovation arrived at a symbolic moment. Postwar America was intoxicated by the dream of effortless living. Domestic chores were being mechanized, from vacuum cleaners to washing machines; now even the act of cleaning one’s car could be delegated to technology. The car wash tunnel became a monument to the modern fantasy: that machines could cleanse not just objects, but our very relationship with the material world.

Inside that tunnel, under the rhythmic slap of rubber brushes and the hiss of water, washing became performance — a ritual of purification staged by automation. Cars emerged gleaming and new, reborn from the mechanical womb.

Shiny surfaces, suburban morality: the mid-century dream of the clean car

By the 1950s and 1960s, the car wash had become part of suburban ritual. Families would drive to the local wash on weekends, the car gliding through neon-lit tunnels that promised to “shine like new.” It was entertainment as much as maintenance — a sensory experience of movement, sound, and transformation.

Advertisements spoke the language of moral hygiene: “Keep it clean, keep it proud.” Clean cars stood for clean lives, clean neighborhoods, clean reputations. In the age of consumer abundance, the car wash mirrored the nation’s psyche: polished surfaces, hidden residues, and the constant need to appear unsullied.

At the same time, the industry became increasingly gendered. Men built and operated the machines; women were cast as passengers or symbols of purity in the glossy brochures. The car wash reflected not just our obsession with appearance, but the cultural politics of who was allowed to clean, and who was supposed to shine.

The environmental confession: when clean began to feel dirty

By the 1980s, a new consciousness began to seep in. Environmentalism forced a reckoning with what had long gone unnoticed — the immense water waste, chemical runoff, and environmental footprint of industrial cleaning.

Modern car washes responded by recycling up to 90 percent of their water, introducing biodegradable soaps, and optimizing energy use. The shift wasn’t purely ecological; it was philosophical. The car wash, once an emblem of consumption, now became a test case for sustainability — a laboratory for reconciling cleanliness with conscience.

In this, it echoed broader cultural anxieties: the sense that every act of purification comes with a stain of its own.

Data, desire, and the algorithmic shine: the car wash enters the age of automation

Today, car washes operate on the frontier of AI and design. Sensors scan each vehicle, tailoring water pressure and timing to its exact contours. Payment happens through apps; data tracks every wash. What began as manual labor has become a seamless choreography of sensors and streams.

And yet, beneath all that technology, the car wash still performs the same ancient function: the symbolic removal of dirt. It satisfies the primal urge to see transformation — to witness the passage from unclean to clean, from chaos to order.

In contemporary culture, the car wash has re-emerged as an aesthetic space. Photographers, filmmakers, and fashion editors return to it again and again because it combines opposites — cleanliness and contamination, utility and sensuality, water and steel. The dripping, glossy surfaces invite metaphor. To clean, after all, is also to expose.

The seduction of soap: when purity and dirt refuse to part ways

The car wash, whether mechanical or metaphorical, is a story about how humans confront imperfection. It embodies the dream of starting over — of emerging gleaming, unmarked, unburdened. But as Scott’s photographs suggest, that dream is always incomplete. Every rinse leaves a trace, every shine a shadow.

More than a century after Detroit’s first “Automated Laundry,” the car wash remains a mirror — reflecting not just our cars, but our culture. We enter it seeking transformation, but what we find is something closer to truth: that the line between dirt and purity is as thin, and as slippery, as a film of soap.

Fendi FW25/26 Special editorial

TEAM: Photography Carly Scott, styling Hannah Elwell, makeup Lydia Ward-Smith using @Chantecaille, hair Myuji Sato using @SamMcknight, nails Ami Rai using @Essie, set design Mitchell Frank Fenn c/o Claudia Williams @Agency41, casting George Raymond Stead, production Cindy Parthonnaud @Sidelines.Studio, production assistant Isaac Hutchings, photography assistant Benedict Moore, digital operator Bruce Horak, retouch Eursa Major, talent Addison Soens @models1