New York, no filter, Daniel Arnold after Instagram: You Are What You Do

Over the last two decades, American photographer Daniel Arnold has recorded moments of humanity on New York streets. His new book: You Are What You Do

An interview with American photographer Daniel Arnold – the volume You Are What You Do, published by Loose Joints

Over the last ten years, Daniel Arnold has emerged from the streets of New York, working within the tradition of American street photography. Born in Wisconsin, he has documented life in Manhattan and Brooklyn, capturing the flow of the city through constant observation of everyday life.

In recent years, Arnold has experienced several personal losses, including the deaths of family members and a pet. Through that period, he held on to photography, continuing to walk the sidewalks of the Big Apple and working on more fashion-oriented commercial assignments. You Are What You Do, published by Loose Joints, closes that difficult chapter and shows a gentler, less irreverent touch, amplifying and preserving the humanity that has always been at the core of his work.

How grief reshaped Daniel Arnold’s vision and led to You Are What You Do

MF: You went through a very difficult personal period. In what way did You Are What You Do reflect that experience?

Daniel Arnold: Twice I watched a friend giving birth, took pictures in the dark, and both times made the mistake of briefly feeling very special. As if some version of that gnarly catharsis wasn’t the source of everybody ever. Same goes for death, my relentless new neighbor. A brief, disorienting spotlight of exceptionalism that settles quickly into a truer, wearier experience of humanness. A lot of the book is old work, but I’m still getting to know it. The expression on my looking face is new. I look worse. Pics look better.

The evolution of Daniel Arnold’s street photography: from irony to intimacy

MF: You Are What You Do feels more intimate and emotional than your earlier, more ironic work. How did the project come together, and how would you describe the final outcome?

Daniel Arnold: There’s work in the book from the day before the edit closed, but it also includes some of my oldest, most seen pictures. They just look different. Maybe nobody else can tell, but they do. You know how every seven years, you find out that seven years ago you were totally full of shit and had no idea what you were doing? Can you imagine trying to explain anything to yourself in 2018? And also, you know how the tiniest breakthrough completely changes the puzzle when you’re really jammed on crosswords or sudoku or solitaire? One letter changes and you have to revisit every clue as if it was new. That’s the game here, just zeroing in on infinity, going over and over the same tracks, holding new insight up to old mystery, bouncing it off strangers, letting go. When you step back, it’s the same process as taking the pictures.

MF: This shift also shows in how physically and emotionally close you get to your subjects. Did you feel more personally involved, and has photography become something deeper for you than just a medium?

Daniel Arnold: I was scratching a certain itch long before people called me a photographer or artist or Arnold daniel or anything. Those intimate pictures were always part of it. Life deepens as you live more and “know” less, but there’s something simpler at play: I entered this space without much intention and got quickly known for a superficial fraction of what I do. Caught up in applause as I may have briefly been, it’s not interesting to me to keep hammering away at a certain kind of street picture because it got popular. It’s always been a broader thing. Life has changed dramatically, but the quieter inside stuff isn’t necessarily new. There’s just more room for it now that the door is open.

New York as a creative ecosystem: how the city shapes Daniel Arnold’s photography

MF: The city of New York is a central element in your work. You’ve lived there for over twenty years; does it still surprise you?

Daniel Arnold: I don’t know that I ask New York to surprise me so much anymore. Once upon a time I had to put a lot of energy and ingenuity into comforting myself between waves of New York surprises. After 20+ years, I surprise myself. Life surprises me. New York is just where I live and belong and that comforts me. But the people do keep it interesting.

MF: What changes have you observed in recent years — the pandemic, political tensions, demonstrations? Have these influenced your work, and would you say the book also carries a political layer?

Daniel Arnold: What’s New York and what’s growing up? I can never tell. “Recent years” have made me humbler, quieter, less impressed, more committed, fatter, madder, balder, subtler, sweeter, less available, more patient in some ways, much less in others. I don’t know if it’s politics or growing up, but “recent years” have gone a long way to distinguish “humane” and “political” as opposites. And given that, investing deeply in humanity is inherently political. Photography is one of the shallower ways of making that commitment, but it’s a gateway drug.

The quiet mechanics of street photography: silence, movement and presence

MF: Silence rarely appears in your images, yet perhaps it exists before or after the shot. Is there a moment of quiet in your creative process?

Daniel Arnold: I’m flattered by that take, and I can’t say it’s wrong — they’re your pictures now too — but the whole process is pretty quiet. I don’t speak, the shutter’s barely a heel tap, even passing thoughts can be disruptive. I actually find the pictures themselves quiet, too. But I’m happy to hear that they’re loud for you.

MF: Bruce Gilden once described street-photographers as “athletic, almost dancing.” Do you relate to that description?

Daniel Arnold: I have been a dancer, but I’m less so lately. There’s pleasure and a high to the performance of working on the street, the dips and football spins, but flamboyance is disruptive and distracting. I’ve said a million times I’m not interested in pictures of people having their picture taken. So I’m alert, but I prefer paying attention to receiving it. Maybe I’m just tired, or turned off by bravado.

MF: Photographing people always involves negotiation between closeness and respect, intrusion and connection. How do you experience this tension?

Daniel Arnold: If every gesture anticipates an image, then almost everything must be performance. My own performance has always made me uncomfortable. If there’s any tension, it’s probably there. My ego embarrasses me. Maybe it’s a disappointing answer, but I don’t go around thinking about street photography or public gesture. I think in pictures more than I think about them. Any analysis only happens in the edit, if at all. So, silent negotiations happen the same way they would for anybody walking down the street, because that’s what I do. I go about my life with curious affection and a camera in my hand and I see what happens.

Ethics, roughness and the raw presence of aging faces in Arnold’s work

MF: Do you ever ask for permission before taking a photograph? Have you ever refrained for ethical reasons?

Daniel Arnold: I have an out-of-control neurotic aversion to bothering people. That can be a reason to ask permission, but more often it’s a reason not to. Ethics are constantly at play, negotiated at calculator speed in every interaction. But that’s not specific to photography. It’s my nature. It’s how I do everything. I’m sure there are slipperier ways of going through the world, but they’re not available to me.

MF: There is often a sense of roughness in your images — in faces, gestures, and details. What does that represent for you?

Daniel Arnold: It all looks beautiful to me. But I get what you mean. It connects to the feelings about performance. People can do many things to beautify their looks, but none of them compare to what time and experience do.

Leaving Instagram, entering fashion and redefining visual authorship

MF: In a world dominated by social media and AI, how do you maintain your visual voice — and what pushed you to step away from Instagram?

Daniel Arnold: There’s no escaping this vapid phone shit and to some degree I need it. Instagram sucks. It all sucks. That’s obvious from outer space. I just put my head down and do my work. I don’t want to compete, cater or brag on my cleverness. No interest. No appetite. I had my fun. It doesn’t help me anymore. In fancy elevators, everybody stares at a little TV to escape the awkward silence. Instagram turns the whole world into that elevator.

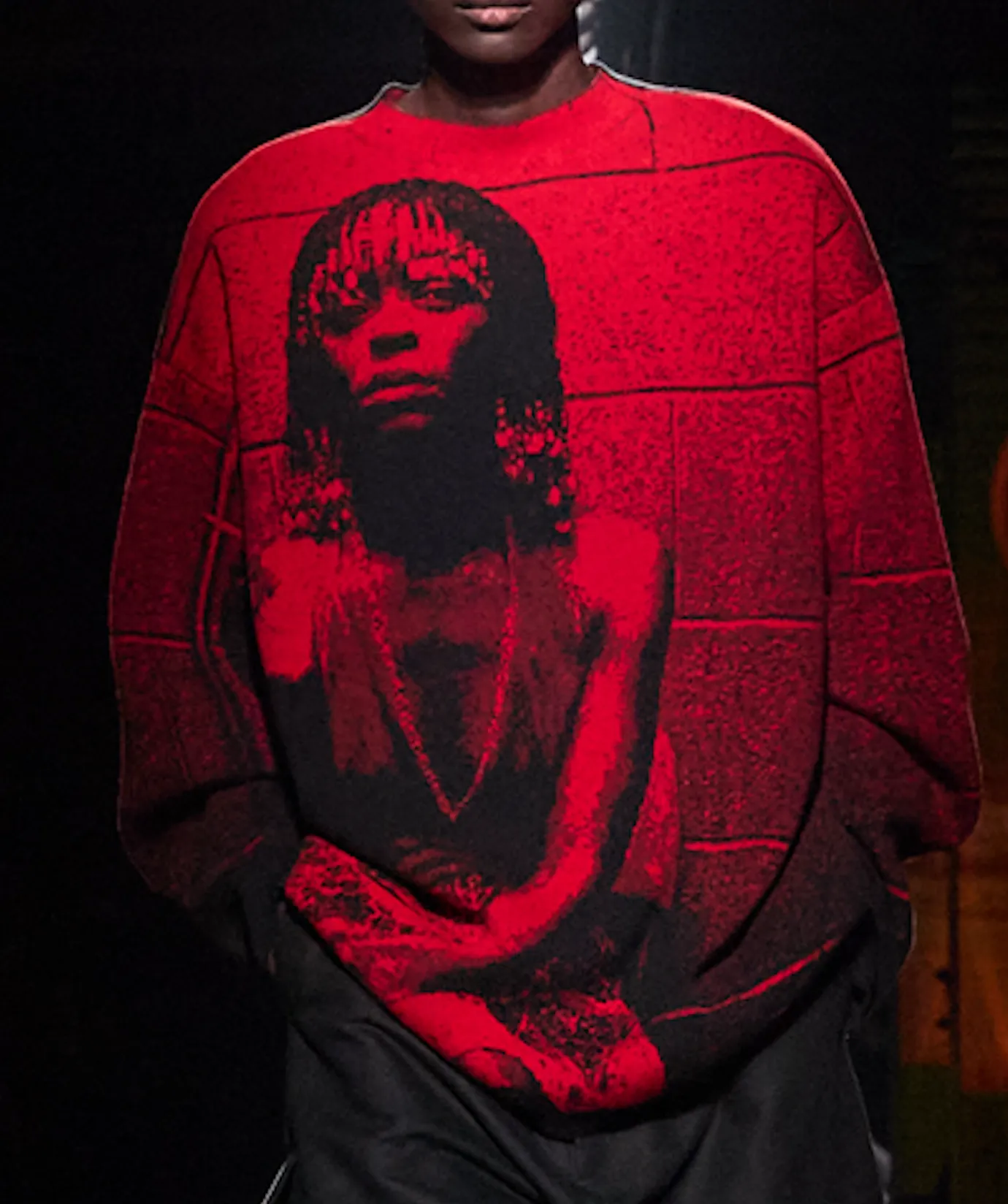

MF: You’ve also moved into more fashion-oriented work. How does that world connect to your personal photography?

Daniel Arnold: I only know how to do what I do. There are no borders. It’s all the same work. Maybe that’s not always apparent in what shows up in ads or magazines, but there’s something in all those jobs that lands back on the big pile. And more abstractly, every day is an education. Higher pressure unlocks cruder instincts.

MF: After more than twenty years, what still drives you to return to the streets with a camera in hand?

Daniel Arnold: It’s a marriage. It’s driven by love and change.

MF: After all this, does life have a purpose? What answer have you found?

Daniel Arnold: Ha damn, this is an ambitious magazine.

Marco Frattaruolo

You Are What You Do by Daniel Arnold is published by Loose Joints