Mary Kelly: seventy years of global conflict through domestic life

On show at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, Mary Kelly uses dryer lint, letters, and press fragments to trace how decades of global conflict leave their mark on the ordinary aspects of domestic life

Mary Kelly’s ‘Post-Partum Document, 1973–1979’ Debuted to Controversy

When Mary Kelly’s ‘Post-Partum Document, 1973–1979’ debuted at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts, a storm of tabloid criticism followed. At its center was a series of used diapers whose smell — according to gallerist Pippy Houldsworth — wafted past a child’s handprints, insect specimens, and over a hundred other souvenirs from Kelly’s then five-year-old son’s life. Now considered one of the most influential exhibitions in conceptual art to date, the show positioned Kelly among a new wave of feminist artists rethinking the boundaries between public and private. Why, they posed at the time, should the messiness of domestic life be washed away? What can dirty laundry reveal about the political landscape that appears so removed from the everyday?

Dryer Lint Compositions in ‘We don’t want to set the world on fire’ at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery

Almost fifty years later, Kelly’s use of domestic detritus has evolved. In ‘We don’t want to set the world on fire’ at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, she creates from lint — that is, the textural fibers which accumulate over hundreds of cycles of washing in her dryer. In a process she pioneered for The Ballad of Kastriot Rexhepi (2001), Kelly uses vinyl-cut stencils to transfer the lint onto rectangular sheets, assembling them piece-by-piece to create fuzzy, meters-wide reproductions of the age’s most circulated images. Their texture is almost photographic, distorted and muddied yet clear enough to discern text and form. Kelly can manipulate the color of the lint by controlling the hue of the socks, shirts and underwear she uses.

In the Circa Trilogy (2004–2016), Kelly uses lint to recreate photographs of social upheaval with this intimately human medium. ‘Circa 1940’ (2016) depicts an English gentleman reading in the debris after Holland House was bombed in The Blitz, while ‘Circa 1968’ (2004) appraises the counter-cultural student riots challenging conservatism in Paris. Though this piece is not on display in ‘We don’t want to set the world on fire,’ a broad fixation on radical thinkers from the time — Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre both make appearances — means Kelly’s admiration of the cause is still felt strongly.

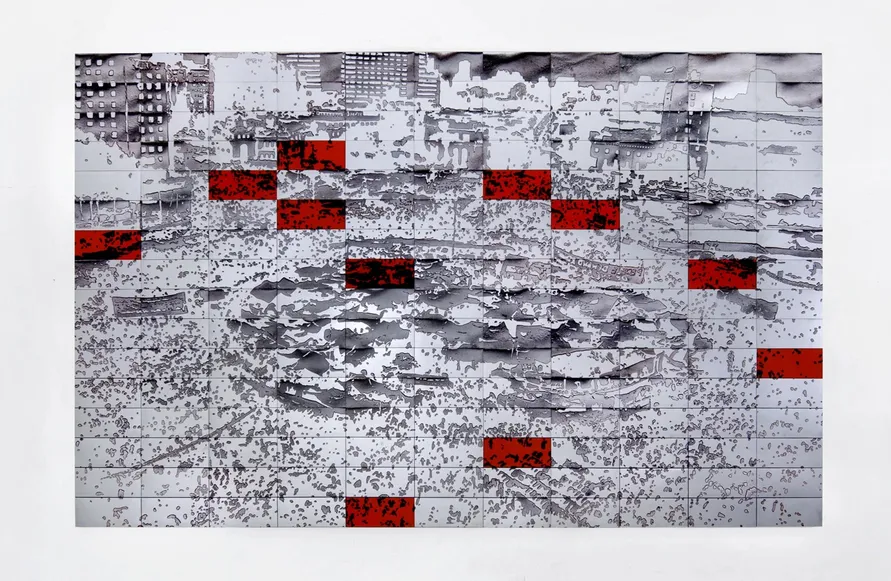

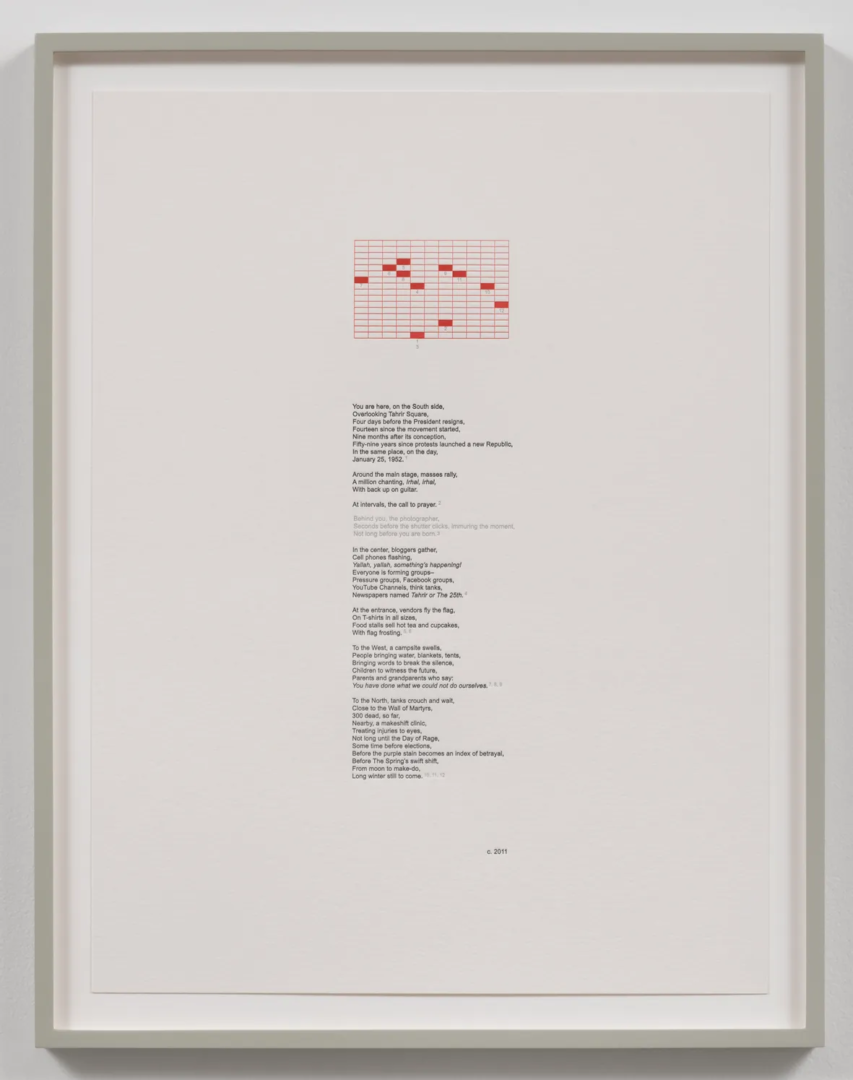

Of the three works, only ‘Circa 2011’ (2016) is on display — it is Kelly’s more contemporary reflection on the fall of Hosni Mubarak’s authoritarian regime during the Arab Spring. In grey, flickering under the light of a projector evoking the buzz of a digital screen, her lint takes form as a circulated image of Tahrir Square in Cairo. Composed of a grid of washing-machine-filter-sized blocks, it evokes an aerial war map. Dotted with red blocks corresponding to a poem about the protests, one line offers a reminder: “You have done what we could not do ourselves.” Another: “At intervals, the call to prayer.”

Newspaper Reproductions

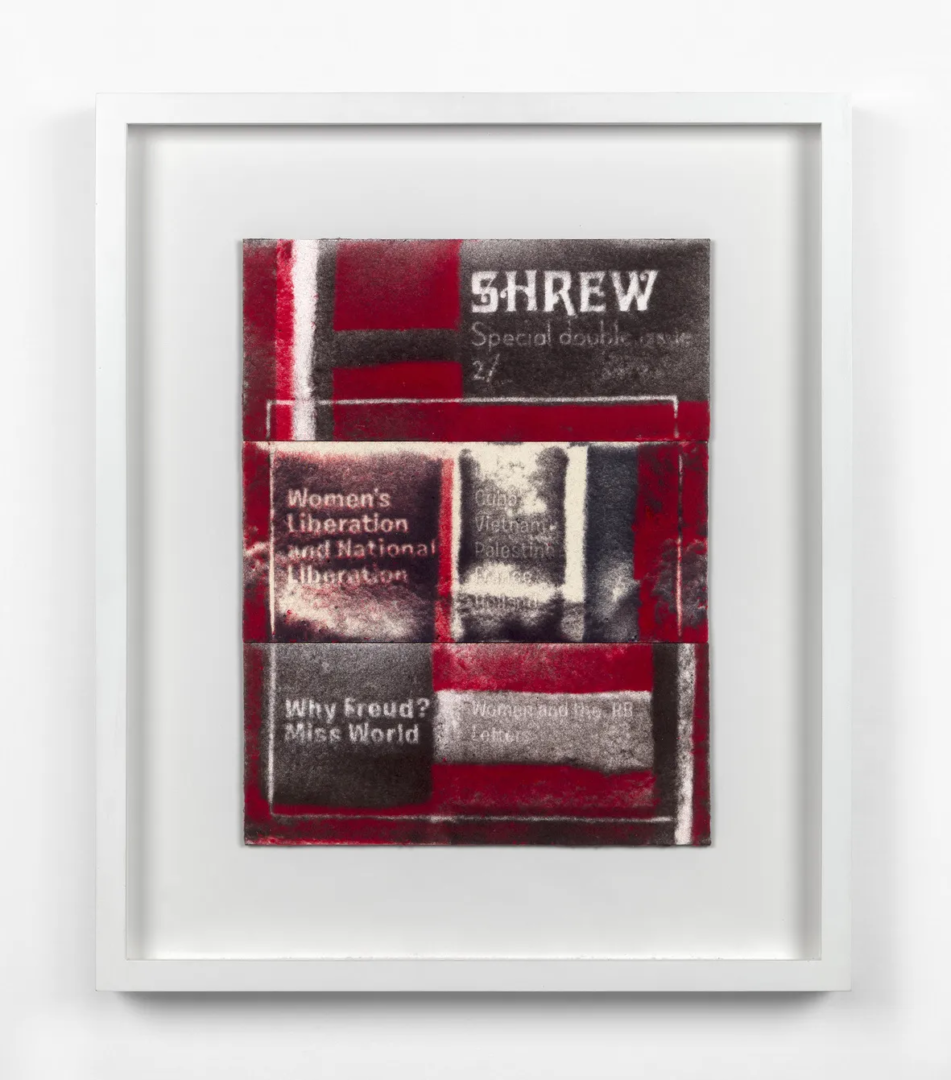

On the adjacent wall, Kelly’s theoretical grounding is hinted at in the intimately sized ‘Shrew, December 1970’ (2017). Scaled up from the smaller, briefly circulated magazine, it establishes her philosophical roots among the anti-establishment movements of the time. It also nods to her known appreciation of Sigmund Freud and psychoanalysis — particularly in Post-Partum Document, 1973–1979.

In dialogue with a reproduction of the titular magazine in ‘Study for Life, April 1945’ (2014), Kelly pulls from two vastly different contexts, highlighting the contrast between the Atom Bomb and World War Two-era morality with the growing dissatisfaction in her own milieu. Titles like “Why Freud?” and “Women’s Liberation and National Liberation’ suggest what Kelly’s perspective may be.

Beyond the technical skill required for turning laundry remains into recognizable images, the medium is startlingly effective in representing the impact of global trauma. After all, clothing carries history. Not only in its rips and stains, but in its very fabric. The lint that accumulates in a domestic dryer is a reminder of how historical events filter through the everyday, their residue remaining well after they’ve been washed.

‘World on Fire Timeline’ (2020) Interweaves the Personal and Political

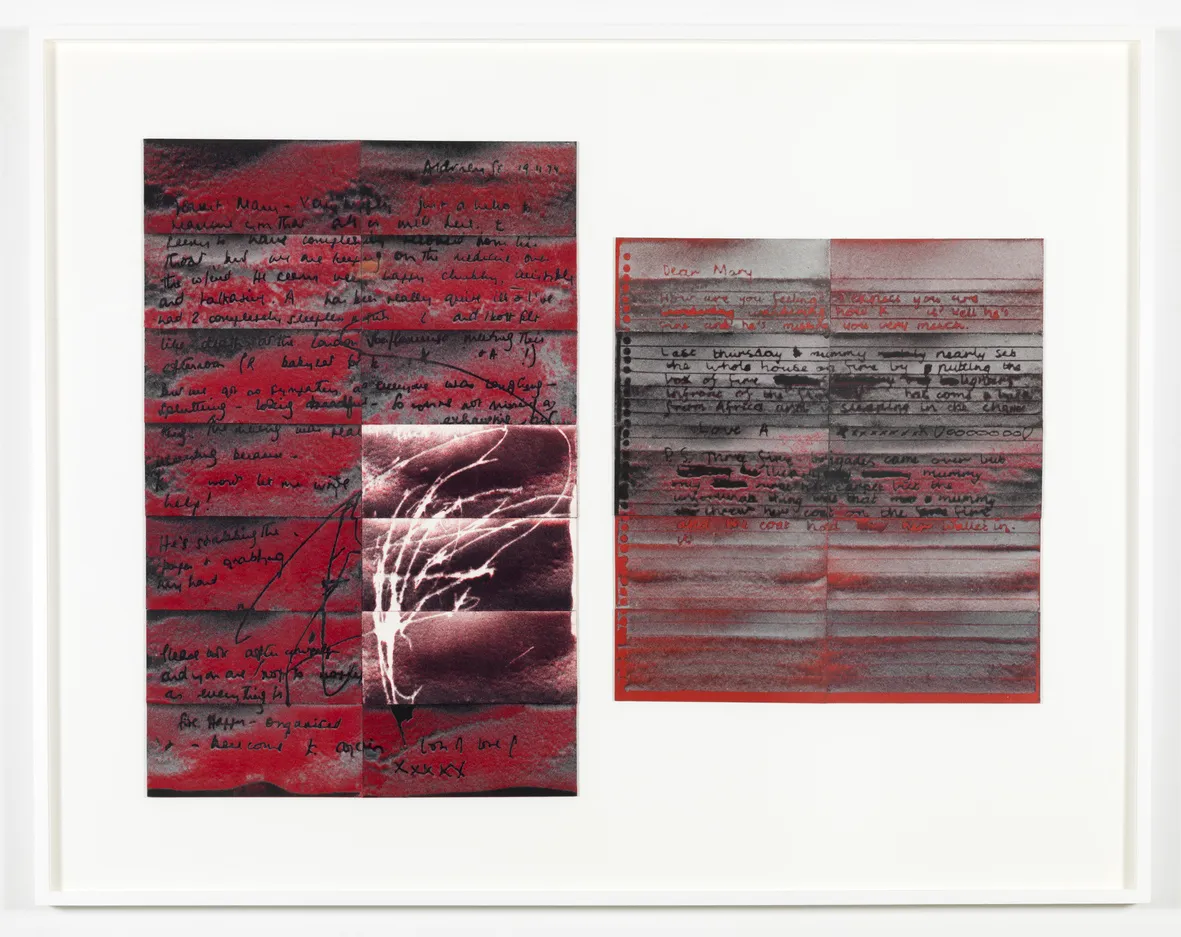

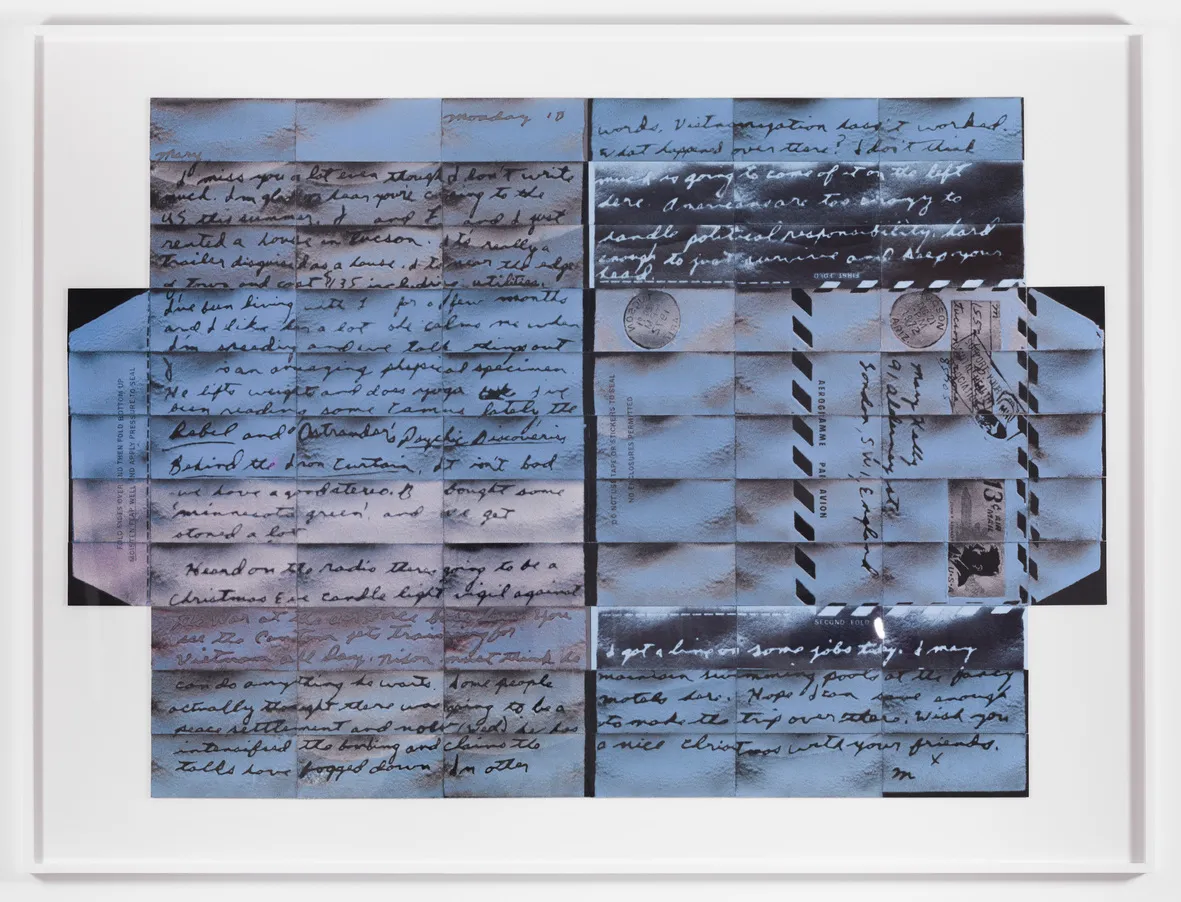

On this human scale, the News From Home series (2017) features large-scale lint reproductions of Kelly’s letters written in the 1970s. This was a time when the artist had relocated from Los Angeles to live in a commune in London. It was also a time when the anti-establishment countercultures of the 1960s had erupted in a wave of landmark civil rights milestones, backgrounded by the Vietnam War’s increasing unpopularity.

“I miss you a lot” begins ‘Tucson 1972’, (2017) a recreation of an airmail letter on show in the exhibition. Kelly’s cursive writing, instructions, and stamps are all built from a grid of over seventy blue lint rectangles. This process blurs some words beyond readability, amounting to a fuzzy homage to what was lost in the passage of time.

What stands out in ‘London 1974’ (2017) — a similar work in red and grey lint — is the glimpse it offers into living. Tracing through the motions of baking and painting, it culminates in a domestic scene where the kitchen is almost set alight. Even in these letters, the presence of motherhood is felt. Beside scribbles in contrasting lint, the text reads, “he won’t let me write… he’s grabbing my hand” in explanation. “Help!” it jokes. In these private moments, the proximity of Kelly’s work to her life is seen most clearly.

While these pieces probe at the overlap of global politics with community and family, ‘World on Fire Timeline’ (2020) literally transposes Kelly’s life across 71 years of conflict. On presentation for the first time in Europe, the piece spans six panels over the length of a full wall. Beginning with the arms race in 1949 and weaving through fragments of the civil rights movements she depicts in Circa Trilogy, (2004-2016) and other series, it ends as we approach the climate crisis in 2020. A 1971 issue of 7 Days magazine sits beside the birth of Kelly’s grandson; a clipped photograph of Simone de Beauvoir is reproduced in lint beside an archival note beginning, “Dear Mary”.

Away From Linear Progress: How Long Until Midnight?

‘World on Fire Timeline’ (2020) also sees Kelly at her most critical. In contrast to the forward-moving progression of the timeline, clockfaces of the Doomsday Clock at key moments reflect a more cyclical pattern. Developed by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in 1947, the clock’s hands edge towards midnight as humanity approaches destruction. Ticking nearer and further from danger across the corners of six panels, it suggests that we are no further from destruction now than we were then. In fact, at 89 seconds to midnight, we are practically closer than at any point in the clock’s history.

Resistance as Solidarity

In the only untreated photograph in the exhibition, Kelly offers an alternative to this futility. In the show’s namesake piece and the first work viewers encounter, the artist appears silhouetted in the desert, the sun dipping beneath the horizon. She is behind a white umbrella, reading: “WE DON’T WANT TO SET THE WORLD ON FIRE.” The image is taken from ‘Peace is the Only Shelter’ (2019), a site-specific piece where the artist ventured into the desert as a tribute to Women Strike for Peace. Reenacting some of their slogans, Kelly lends her weight to the group’s protests against nuclear weapons testing. A contrast to the futility of ‘World on Fire Timeline’ (2020), it offers an alternative approach to conflict — one grounded in the feminist notion of resistance as solidarity.

Paying homage to the climate crisis in its title — and nodding to the fact that lint is highly flammable — ‘We don’t want to set the world on fire’ is a recentering of the personal, a reminder to remember the human face of crises that evade our attention.

Joshua Beutum