The art of exit: fashion designers writing their final chapter

From Sunnei’s auction-like finale to Alexander McQueen’s silent salon and Tom Ford’s boardroom battle: each exit reshaped not only a personal career but the direction of entire fashion houses and the industry itself

Sunnei’s founders Simone Rizzo and Loris Messina staged their Spring/Summer 2026 show as a live auction. Hours later, they declared their departure. Days later, Silvia Venturini Fendi closed her era, stepping down as the last family creative director of the Roman maison. These gestures did not stand alone: they entered a long record of exits that, from John Galliano to Raf Simons, from Hedi Slimane to Tom Ford, have redefined what it means to leave a fashion house.

Departures punctuate the history of brands with ruptures and transitions, with shows that become final manifestos or silences that resonate louder than any runway. The farewell of a designer is both an end and the beginning of something else: a shift in power, a change of identity, the redefinition of a house’s future.

The Exit Itself as a Final Design: Sunnei

Simone Rizzo and Loris Messina founded Sunnei in 2015 in Milan. Their idea was to create a label rooted in a new Italian minimalism, but nourished by irony and collective spirit. The brand started from ready-to-wear and quickly expanded into footwear, eyewear, lifestyle, and a strong digital presence. From the beginning, Sunnei distinguished itself by staging shows outside the fashion establishment: under viaducts, in empty swimming pools, on suburban streets. They developed a community around Palazzina Sunnei, their hybrid headquarters that functioned as office, showroom, and cultural hub.

Over the years, the duo led the company through growth phases, culminating in 2020 with the sale of a majority stake to the holding Vanguards Group, which also controls Nanushka. This allowed expansion but also introduced new corporate dynamics.

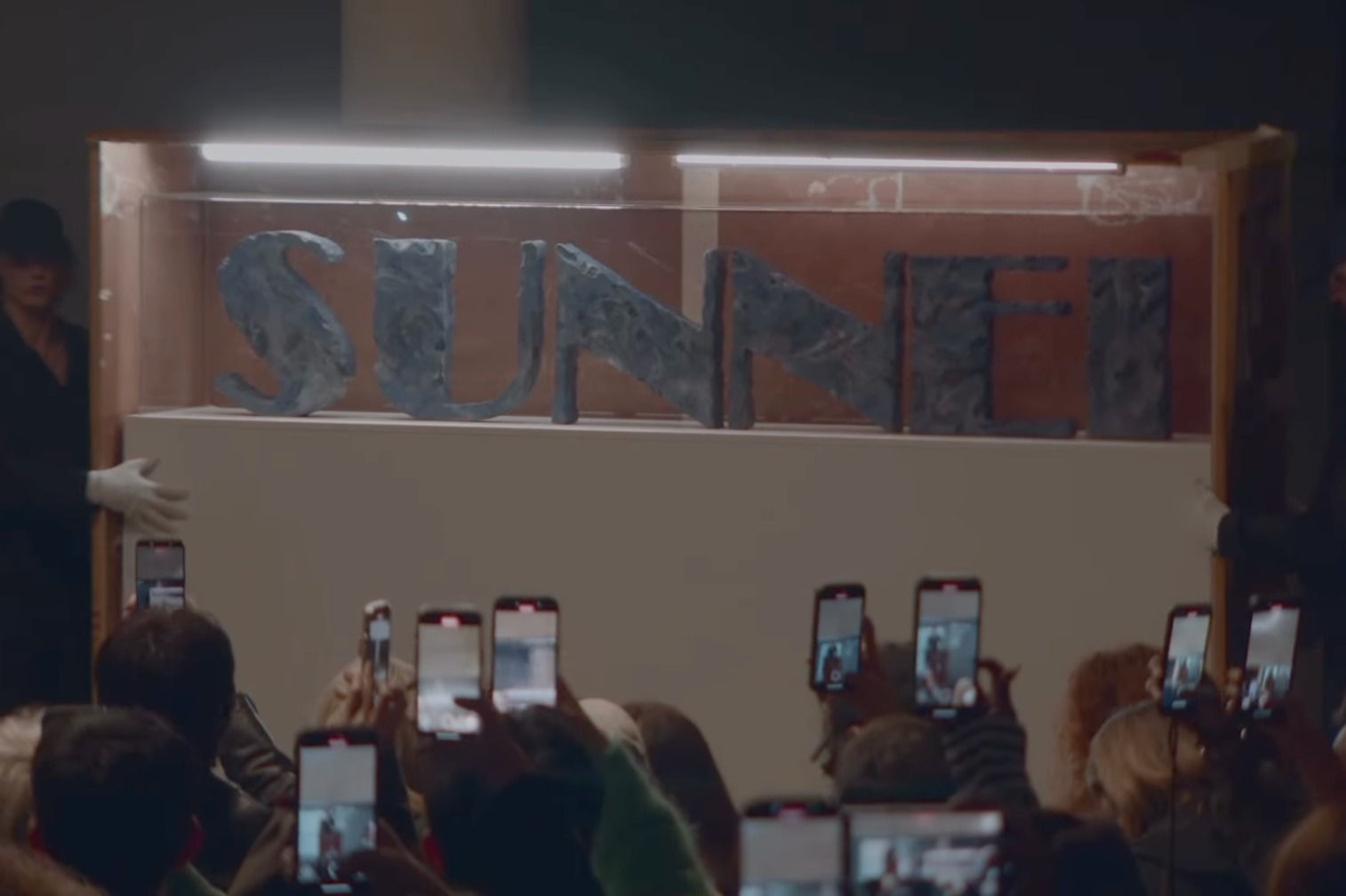

On September 20, 2025, during Milan Fashion Week, Sunnei presented its Spring/Summer 2026 collection. It was not a traditional runway but a satirical performance: an auction staged as a show. A Christie’s-style lectern stood at the front, lettered in gold. Guests were handed catalogues listing the “lots”: garments, accessories, even the founders themselves. Staff distributed scratch cards with fictional “fashion dollars.” A giant wooden crate was opened to reveal the Sunnei logo as Lot 1. Another revealed Rizzo and Messina, offered as Lot 2.

A voice declared the performance “an urgent act.” It was a critique of how creativity is monetized, of how fashion itself has become speculative value. Hours later, a press note announced their departure. Both gestures—the auction and the communiqué—took place the same day, transforming the exit into a final artwork. Sunnei left not with a collection, but with an idea: the exit itself as design.

This way of leaving echoed their whole trajectory. Sunnei had often turned the mechanics of fashion upside down, inviting the public to rate collections in real time with scores, or creating initiatives that blurred art, retail, and performance. Their departure closed the circle: leaving the brand not with silence, but with a spectacle that framed exit as creation.

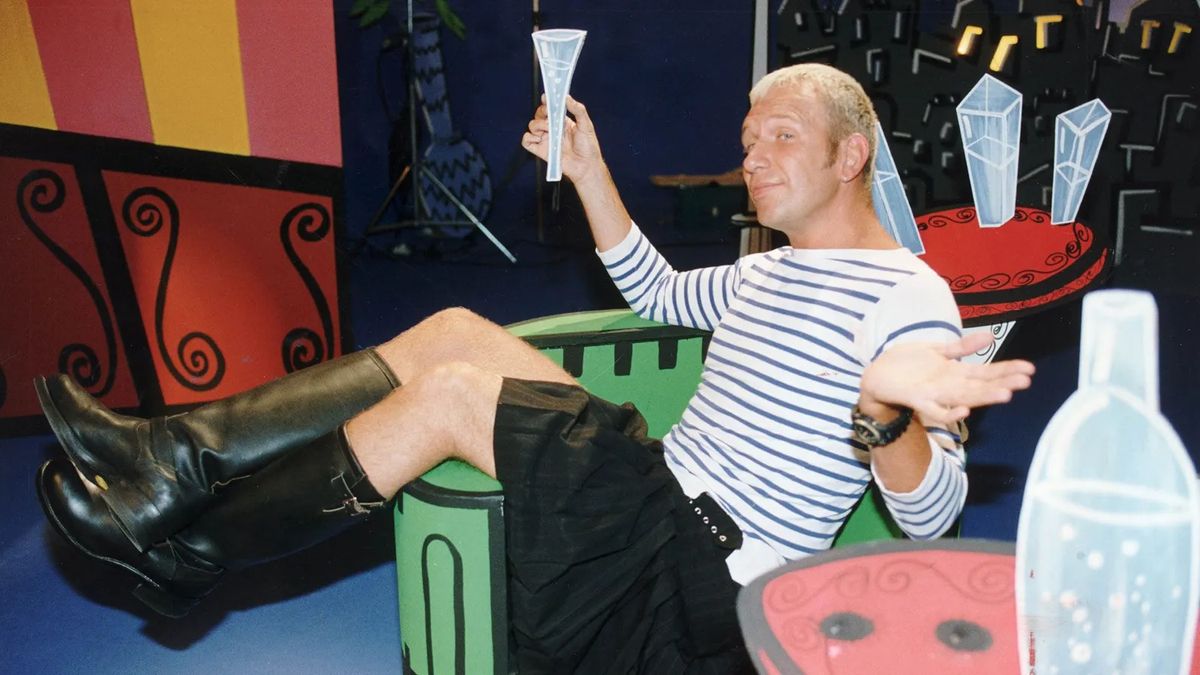

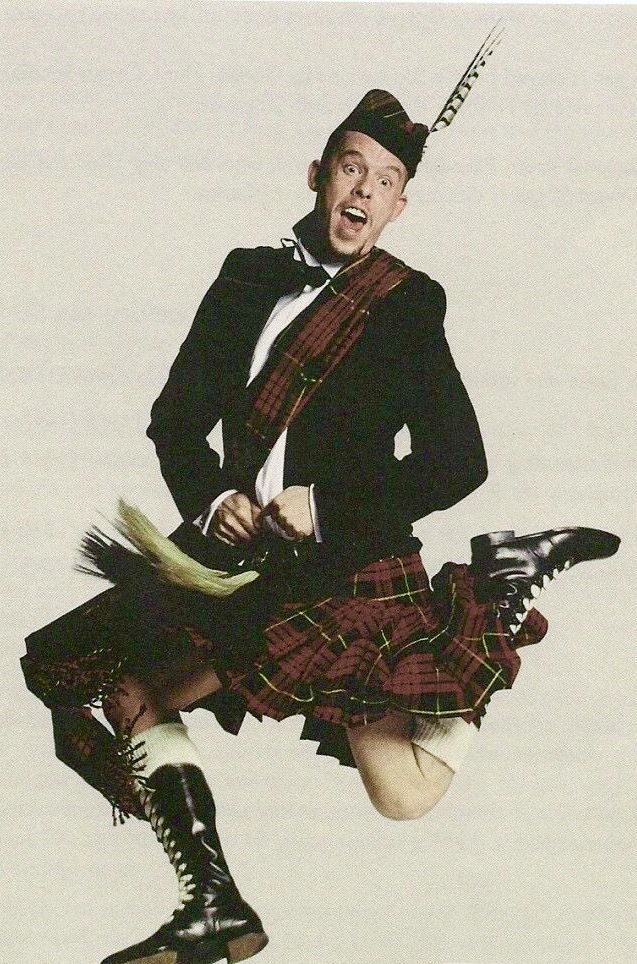

A Farewell that Ensured Continuity: Jean-Paul Gaultier

Jean-Paul Gaultier’s departure marked the end of an era but also the invention of a new model. Often described as fashion’s enfant terrible, Gaultier began in the 1970s, learning under Pierre Cardin and launching his label in the early 1980s. He built a universe of recurring elements: the corset, the marinière sailor stripe, denim reconfigured as couture, tailoring that crossed gender boundaries. He introduced lingerie and fetish codes into the mainstream, bringing subcultural symbols into the most codified luxury arenas.

By 2015, Gaultier closed his ready-to-wear line, declaring that the frenetic pace of the industry no longer allowed him to design freely. He concentrated on haute couture, where he experimented with upcycling, reusing archival fabrics, and bringing street symbols onto the most artisanal runways.

In January 2020, Gaultier announced that his next couture show would be his last, coinciding with his 50th anniversary in fashion. The farewell show took place at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. It opened with Boy George performing Back to Black. More than 200 looks followed, an encyclopaedia of Gaultier’s career. At the centre of the spectacle was a coffin topped with the maison’s iconic cone bra—an image that referenced William Klein’s 1966 satire film Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? The coffin then opened, revealing a model in a white dress, a metaphor of rebirth.

The casting underlined his influence: Rossy de Palma, Dita Von Teese, Erin O’Connor, Bella and Gigi Hadid. The clothes combined his codes—corsetry, stripes, denim—with new garments made from recycled textiles. Gaultier himself came out for the final bow in blue worker’s overalls, his uniform since youth.

But the real innovation was organizational. After his farewell, the house adopted a rotating system: guest designers would reinterpret Gaultier’s archive each season. Chitose Abe of Sacai, Glenn Martens of Y/Project, Olivier Rousteing of Balmain, Haider Ackermann—all took turns. In this way, the archive became the core of continuity, proving that departure did not have to mean rupture. Gaultier created a model of leaving that allowed the house to survive him while preserving the freedom he embodied.

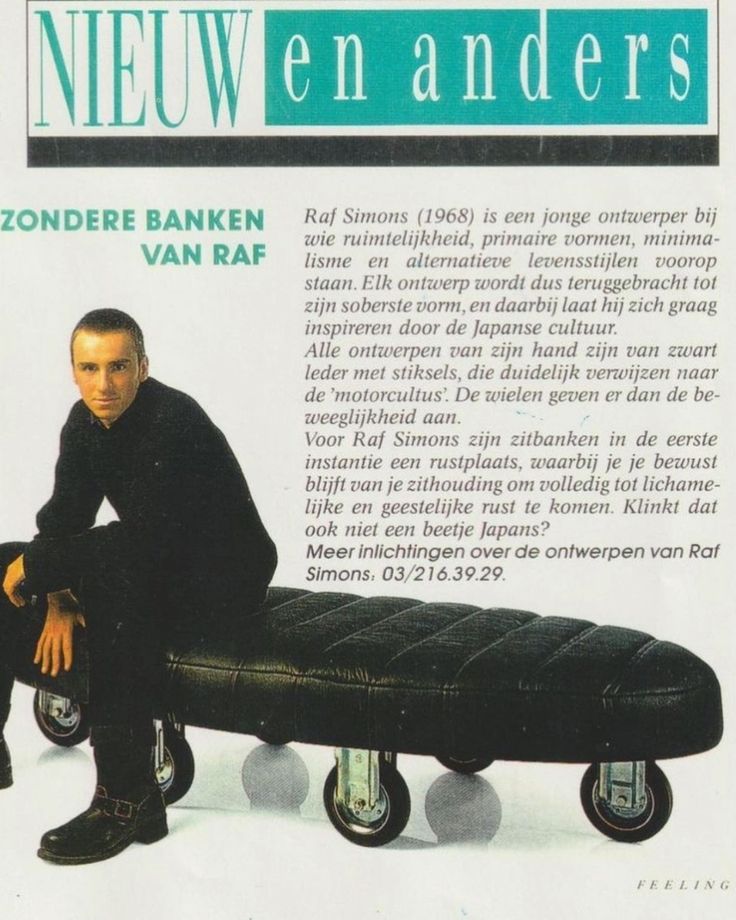

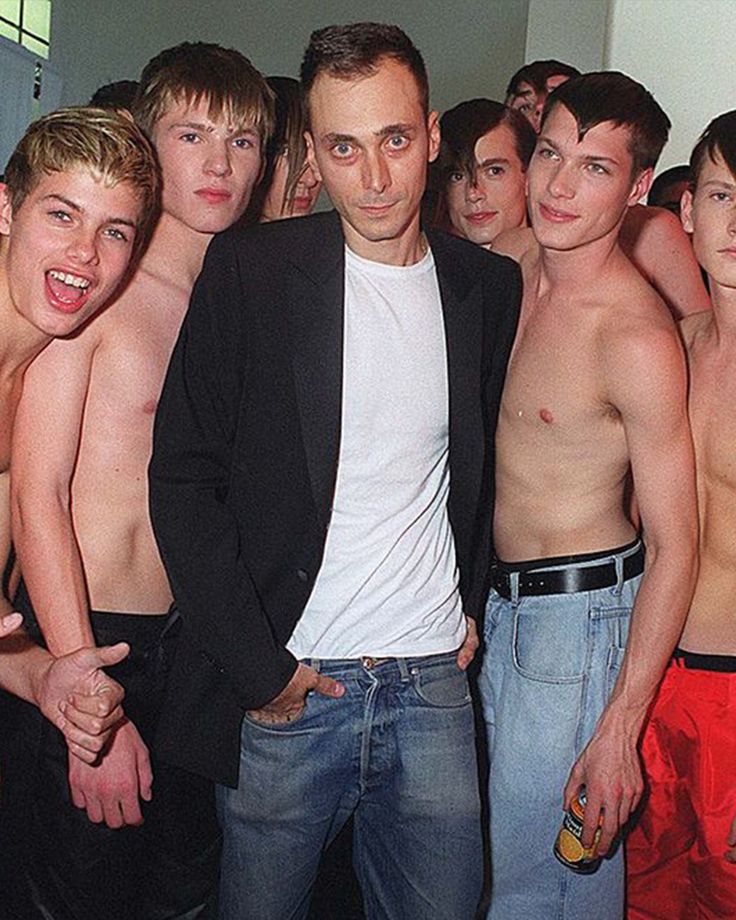

Transitions Toward a Chapter of Lasting Success: Raf Simons

Raf Simons’s exits reveal another pattern: the tension between corporate houses and personal authorship. Simons became creative director of Dior in 2012, after John Galliano’s dismissal. His task was formidable: to restore the house’s credibility, modernize its image, and stabilize its collections. Simons introduced his own language: clean silhouettes, architectural structures, a focus on colour and minimalism. He reinterpreted Dior’s bar jacket, florals, and couture volumes with restraint, a counterpoint to Galliano’s theatricality.

His tenure produced collections praised for elegance and discipline. Yet in October 2015, after three and a half years, he announced that the Spring 2016 show would be his last. He chose not to renew his contract, citing a desire to dedicate more time to his eponymous brand and his personal life. The house, left without a creative director, relied on its in-house studio until Maria Grazia Chiuri’s appointment in 2016.

Soon after, Simons moved to Calvin Klein, where he became chief creative officer in 2016. He unified all the brand’s lines—jeans, underwear, ready-to-wear—under one vision, introduced a new logo, and developed collaborations with the artist Sterling Ruby. His American reinterpretation mixed pop culture and conceptual art, quilted Americana and Warhol prints. Yet in December 2018, eight months before his contract’s end, he left due to disagreements with PVH over commercial performance.

These exits were not failures but transitions. They led to his partnership with Miuccia Prada, announced in 2020, in which the two shared creative direction. That dual role represented a new chapter: not an exit into solitude, but into collaboration. Simons’s departures, from Dior to Calvin Klein, trace the struggle of balancing independence with corporate roles—necessary steps toward a chapter of lasting success.

An Image Built, a Departure at its Height: Hedi Slimane

Hedi Slimane’s trajectory at Saint Laurent shows what it means to leave at the peak of image-building. Slimane began his career in the 1990s at Yves Saint Laurent, before moving to Dior Homme, where he revolutionized menswear with skinny tailoring and a rock aesthetic. In 2012, he returned to YSL with full control over design and image. One of his first moves was renaming the ready-to-wear line Saint Laurent, echoing Yves’s 1966 Rive Gauche revolution.

Slimane’s vision was total: he photographed the campaigns, cast musicians and underground icons like Marilyn Manson and Courtney Love, and reintroduced gender play in menswear. Under his tenure, revenues doubled. The brand became a global uniform of slim black suits, leather jackets, and grunge glamour.

His exit was staged with his typical dramaturgy. In February 2016, he presented part of the Fall collection with a 93-look show at the Hollywood Palladium in Los Angeles, a celebration of the link between fashion and rock music. Weeks later, on March 7, he presented “La Collection de Paris,” a couture-like line, in the restored couture salons of Yves Saint Laurent on the Left Bank. It was a return to the origins: numbered looks, golden chairs, silence.

On April 1, 2016, Kering and Saint Laurent issued a joint communiqué announcing his departure. Within days, Anthony Vaccarello was named successor. Slimane left after having rebuilt Saint Laurent’s identity from scratch. His tenure proved that an aesthetic, once installed, can outlast the designer. His exit was less an end than a transfer of image.

Nature of a Departure and the Absence of the Designer: John Galliano at Dior

If Slimane’s departure was theatrical, Galliano’s was abrupt and scandalous. John Galliano became creative director of Dior in 1996, after his work at Givenchy. His Dior shows became legendary: narratives staged with references to history, art, and culture, theatrical constructions of garments and stories.

In February 2011, a video surfaced showing Galliano making antisemitic remarks in a Paris bar. The scandal exploded. On March 1, Dior suspended him. On March 4, the house presented its Fall/Winter 2011 ready-to-wear collection at the Musée Rodin, without Galliano. At the end, the atelier staff appeared on the runway, bowing in place of the absent designer. Days later, Dior officially dismissed him.

Galliano’s departure became a textbook case of how reputation and governance intersect in fashion. The absence of the designer at the show was more eloquent than any presence: it signaled rupture, a fracture that the brand needed to heal through collective work. Galliano’s career resumed years later at Maison Margiela, but the way Dior closed his chapter remains emblematic: the atelier taking the bow, marking the absence as the narrative.

Angels and Demons: The Silent Posthumous Salon

Some departures are not resignations but tragedies. Alexander McQueen, who had worked on Savile Row, at Givenchy, and under his own label, died by suicide on February 11, 2010, days after his mother’s death. His final collection, intended for Autumn/Winter 2010, was left unfinished: sixteen looks cut on the mannequin.

A month later, in Paris, the collection was shown in a salon format. No music, no spectacle, only models circling a gilded room. The clothes drew on Medieval and Renaissance painting, on Byzantine iconography, with gold and red brocades, angels and demons. Each garment was unique, like a relic. The show was not just a presentation but a requiem.

Sarah Burton, his long-time collaborator, was appointed creative director later that year. But McQueen’s exit was not one he designed—it was an absence that fashion transformed into myth. The silent salon crystallized his legacy, a farewell imposed by death but staged with dignity.

A Subtle but Telling Shift in Name: Martin Margiela

Martin Margiela’s departure was subtler but equally symbolic. He founded Maison Martin Margiela in 1988 with Jenny Meirens, introducing deconstruction, garments repurposed from found clothes, anonymity, and a refusal of celebrity. Margiela never appeared in public, never took bows.

In December 2009, the company confirmed his departure after months of rumors. The reason: creative exhaustion and frustration with commercial pressures. The maison continued without naming an immediate successor, relying on a team.

In October 2014, John Galliano was appointed creative director. When he presented his first collection in January 2015, the name had been shortened to Maison Margiela. That subtle change signaled a new chapter, a formal separation from the founder’s presence. A designer who had built anonymity left behind not silence but a house that could evolve without him.

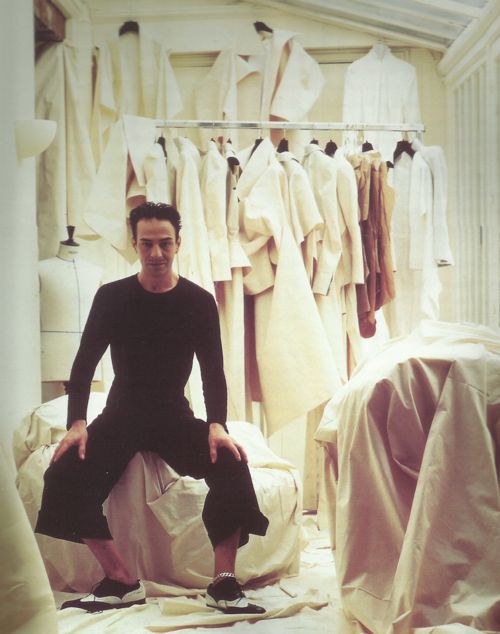

The Corporate Control Exit: Tom Ford

If Margiela’s exit was silent, Tom Ford’s was corporate. Ford joined Gucci in 1990 and became creative director in 1994. He revitalized the house with tailoring, sleek branding, and a sexualized glamour that defined the late 1990s and early 2000s. Alongside CEO Domenico De Sole, he transformed Gucci into one of the most profitable fashion companies of its time.

But in 2004, conflict arose with the group’s new owner, PPR (today Kering). Ford and De Sole sought greater creative and business control over the Gucci Group. Negotiations failed. On April 30, 2004, both exited.

Ford’s final collection, Fall/Winter 2004, revisited his codes: sleek tailoring, cut-out gowns, jewel tones. He brought back models from his heyday, making the collection both a closure and a statement of continuity. His exit was not a quiet bow but a corporate battle that redefined the balance between designers and conglomerates.

Assassination and the Line of Succession: Gianni Versace

Some exits are violent ruptures. On July 15, 1997, Gianni Versace was assassinated outside his Miami Beach villa. His death shocked the world and closed a chapter that had redefined Italian fashion’s image globally. Versace had turned his shows into media spectacles, merging supermodels, pop stars, and art into one stage. He gave Italian fashion an aura of confidence and power.

After his death, the house remained in family hands. Donatella Versace became creative director, Santo Versace chairman, Allegra Versace inheritor of a majority stake. Donatella continued for nearly three decades, until 2025, when for the first time a non-family designer was named. The succession after Gianni’s death was both necessity and trauma: a reminder that in fashion, the designer’s presence is sometimes erased not by contract, but by fate.

Closing the circle: the Fendi case

The narrative of departures came full circle in 2025 with Silvia Venturini Fendi’s farewell. She had been the last member of the founding family still actively designing, leading accessories and menswear, co-creating with Karl Lagerfeld, and embodying the Roman maison’s heritage. Her step-down as creative director marked the end of family leadership in a major Italian house. In the same days, Sunnei’s founders left after staging their exit as an auction.

Two exits, very different in form, coincided: one theatrical and ironic, the other solemn and institutional. Together, they signaled the same reality: fashion is an industry of exits as much as of arrivals. Each departure is a design in itself, a narrative that shapes how we read the history of the house and of fashion at large.

Text: Melis Özek