The Fashion Month: is there any sustainability? Only 10 looks here to talk about

Ten looks out of over two thousand: a selection that calls for sustainability, after witnessing a month of non-stop fashion shows – we ask for no plastic, no prints, no fluorescent colors

The Fashion Month: ten looks out of over two thousand

Early October marks the end of the Fashion Month. On this page, a selection of just ten looks: a choice of ten looks out of all – how many are there, two thousand, three thousand looks? We could guess that every show averages fifty looks, some with forty, some with eighty – they are more when both men’s and women’s collections are presented together. In this review, we’ve chosen just ten looks – those that might be considered the best.

A total of ten out of over two thousand. Including the shows and some presentations. Too many, right? This confirms how the fashion system collapses under consumerism. Revenues are dropping, worries are rising. Some analysts predict 2025 will be better – but outside the industry, when talking to the general audience, there’s a palpable sense of annoyance and frustration toward fashion.

Ten looks out of over two thousand ones: observations, long-term thinking

Ten looks out of over two thousand, I repeat. Shows across four cities: New York, London, Milan, and Paris. If readers want to consider these ten looks the best, that’s fine with me – but I won’t sign off on it. I’m simply describing – nothing more. Here at Lampoon, I never want to use adjectives: we don’t offer evaluations or opinions, we merely present observations – it’s up to readers to form an opinion. For me the writer, these ten looks are the most suitable for generating ideas.

Just four years ago, we had a pandemic crisis – they said everything would change, but everything has returned to how it was in 2019. The same rush, the same excess. Self-congratulatory communication, and the product coming before the message – still squeeze a clientele with little culture but plenty of money who want to emulate their favorite celebrities. It’s a vicious cycle: the deeper it sinks, the stronger it becomes. These sentences may seem like unsupported arguments: I could offer examples and counterexamples, but we could continue to argue and preach endlessly.

It took Hermès almost two hundred years to get here. Next year, Fendi will celebrate a hundred years. I’m seeking a more logical analysis. Today, companies are led by managers, not by founding owners. These companies are owned by funds that speculate on financial mechanisms, revenues, and profits. There’s no room for long-term thinking anymore, because manager performance is evaluated over a year or three years. Long-term thinking is now rendered impossible by financial analysis that reports biannual – yet it was strategic -term thinking that built these brands.

Ten looks out of over two thousand: no upholstery prints, no fluorescent colors, no plastic

We say, ten looks out of over two thousand. Where to start? Let’s discard all printed fabrics – where printing on fabric requires chemical solvents and synthetic fibers that absorb ink without smudging. Why, then, should we dress in tablecloths? Try to see yourself from outside this craving for upholstery: why should you look like a vase of flowers, a polka-dot flag, an Indian blanket? Doesn’t your intellectual rigor lead you to turn down the noise? Likewise, no fluorescent, aggressive colors: who are you trying to catch attention with, like a neon traffic light? Are you really dreaming that everyone turns to look at you?

Ten looks out of two thousand. You won’t find plastic, because we’re not putting on what pollutes us most. There’s an illusion – it’s impossible to dress without plastic. Plastic is everywhere. We’ll be dirty anyway – nylon, polyester, elastane. In this selection, we’ll try to avoid plastic as much as possible.

Similarly, we’ll avoid commercial looks – those outfits in a show that could already be in our wardrobes. We’ll all keep wearing a white t-shirt – but that doesn’t mean we care to see one on the runway. A runway can work as pure styling: an assemblage job, pieces that wouldn’t stand out on their own but gain strength through a montage; – the runways that interest us are those working on design: outfits that focus on material, cut, and the effort to evolve an artisanal idea into an industrial process. For outsiders, it might seem absurd to imagine how complex it is to industrialize an alternative to a simple button. The term craftcore is still used – when the creative idea comes from craftsmanship; when the creative develops craftsmanship skills and not when craftsmanship must find solutions for creative ideas.

In order of appearance, here are the 10 choices:

1. Alaïa – Look number 7

New York. An elaborate, elastic knitwear that hugs the human body as if gravity didn’t exist. This is Alaïa. Knitwear is made possible by synthetic fibers, which release microplastics with every wash. It’s arguable that such garments shouldn’t be put in the washing machine, but creativity based on lycra and polyester is hardly contemporary today. Conversely, form and design linearity reflects an attitude that participates in current fashion discourse. At Alaïa, the look number 7 is a single piece, a denim coat: the seam is offset at the waist, the collar deviates from its Seventies reference and finds a bourgeois cadence. The denim is likely woven with cotton mixed with elastane, which diminishes its regard – but (one) I can’t confirm this, and (two) the resulting shape commands respect.

2. The Row—look number 2 (presentation)

New York. Another coat. The fabric is a cotton twill, gabardine, perhaps waxed. The fabric is abundant at the front. The first to propose this tailoring was Yves Saint Laurent, who himself developed a concept from Cristobal Balenciaga, and which Giorgio Armani later stylized. The open coat appears cumbersome when walking but pleasant in how it fits the body. When buttoned up, it regains its geometry. The color is earthy, mud like, consistent. It’s a moment of vigor for The Row, which successfully evolves quiet luxury from some fashion that isn’t fashion but well-made clothing.

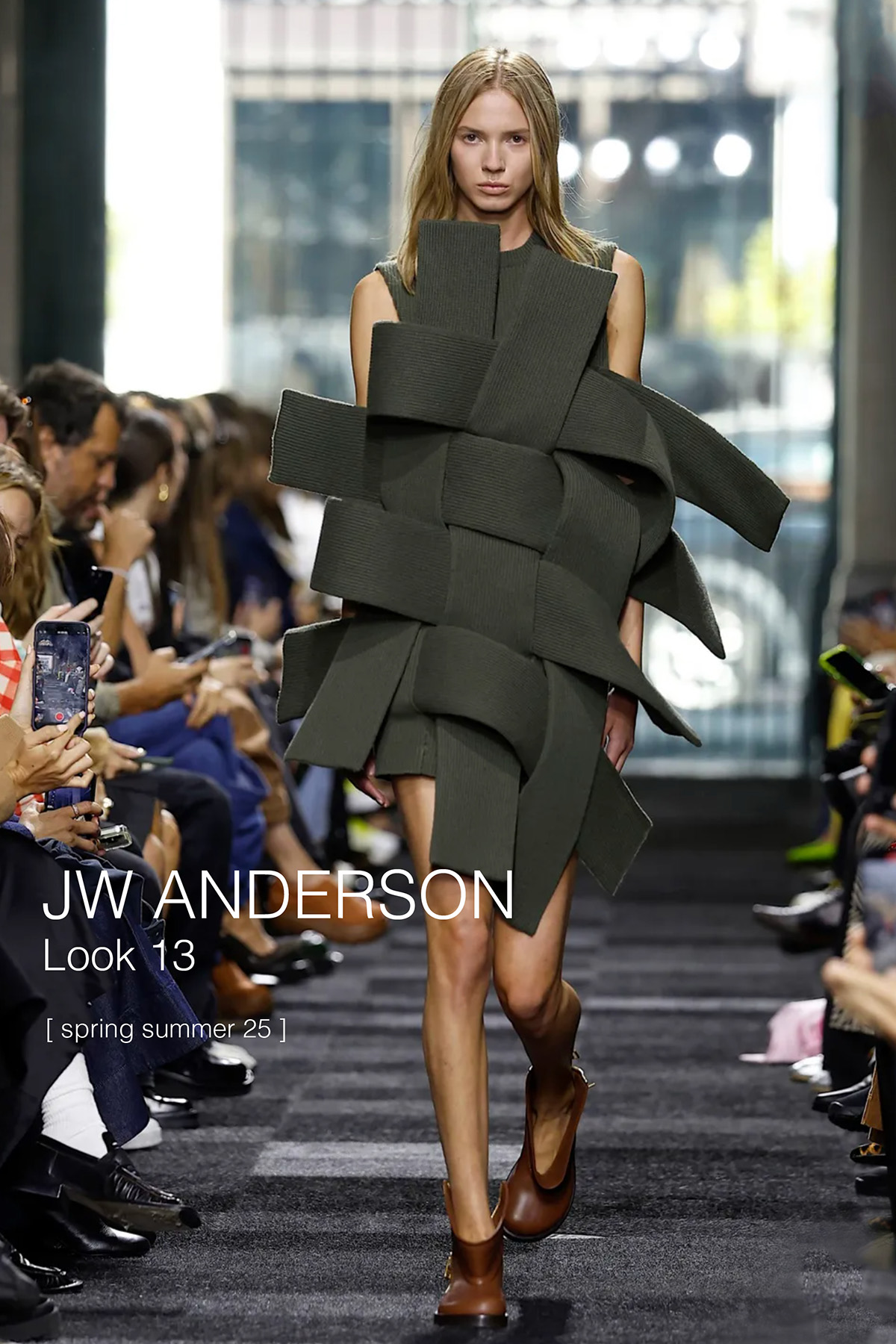

3. JW Anderson—look number 13

London. Panels of ribbed knit, probably supported by polyurethane and elastic fibers. The macro braid is a bold design, perhaps difficult to wear. One of those pieces that makes you wonder when a woman would ever wear it—but once she puts it on, she revels in it. The volume works, the movement on the body, the contradiction of every tight fit that must highlight sensuality. Dressing can become an intellectual desire. Jonathan Anderson designs the costumes for Luca Guadagnino’s films—we haven’t yet seen Queer, but this piece is still a nod to the tennis of Challengers.

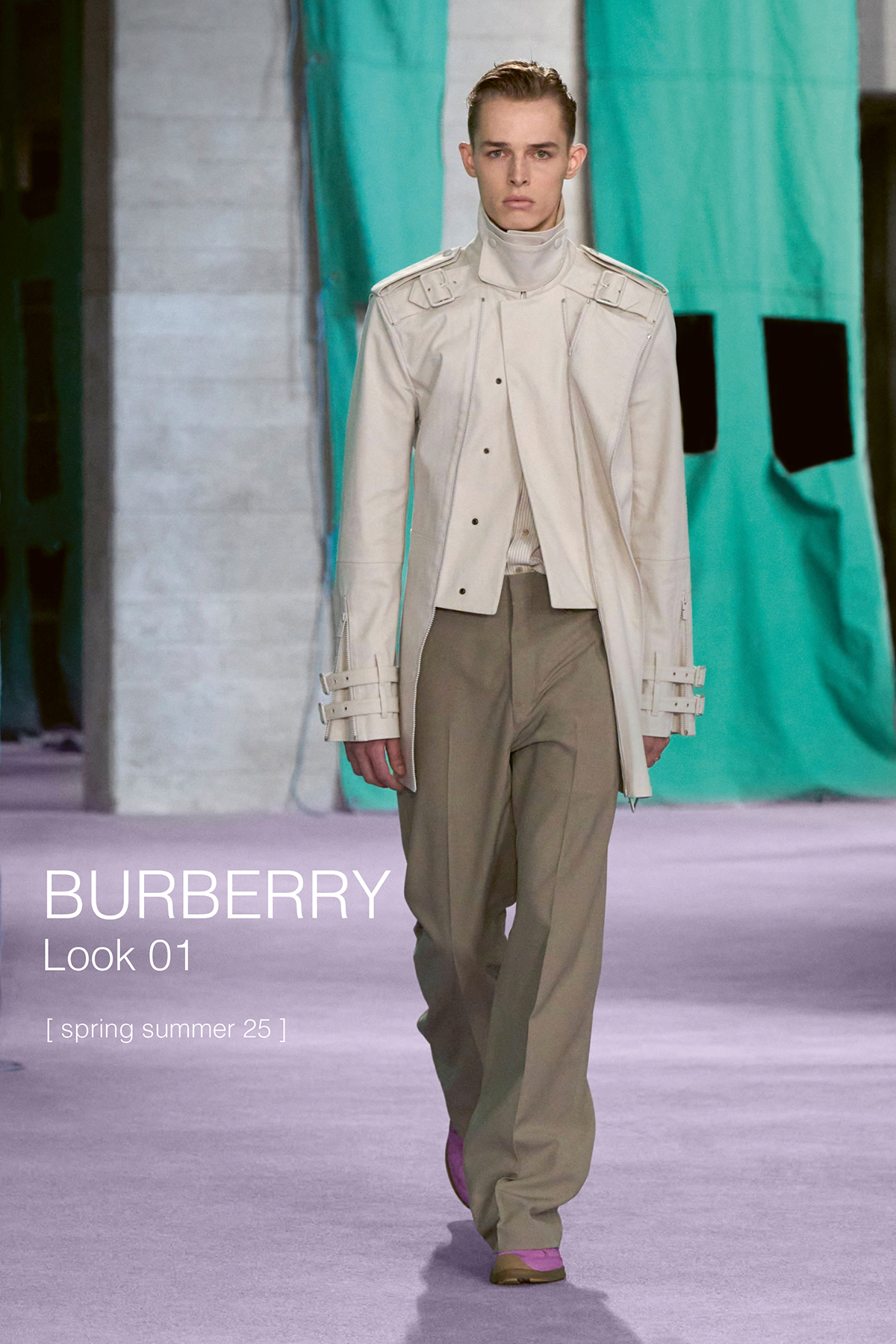

4. Burberry, look number 1

London. The design becomes dramatic without falling into romanticism: it works due to bold tailoring, a consistent color scheme, and the detail of a purple shoe that clashes yet ends the thought like a period at the end of a sentence. Straps on the wrists, straps on the shoulders. The rectangular collar, a revolution of the English gabardine—or a gendarme’s jacket. Daniel Lee seemed to not have fully recovered from his move; it seemed like London wasn’t stimulating him as much as Milan. With this collection, he might reignite: the design knows how to elaborate on the codes of the trench coat. Today, Burberry isn’t strong: the blame can be placed on management, timid communication, or a collection that might not be able to be commercial enough.

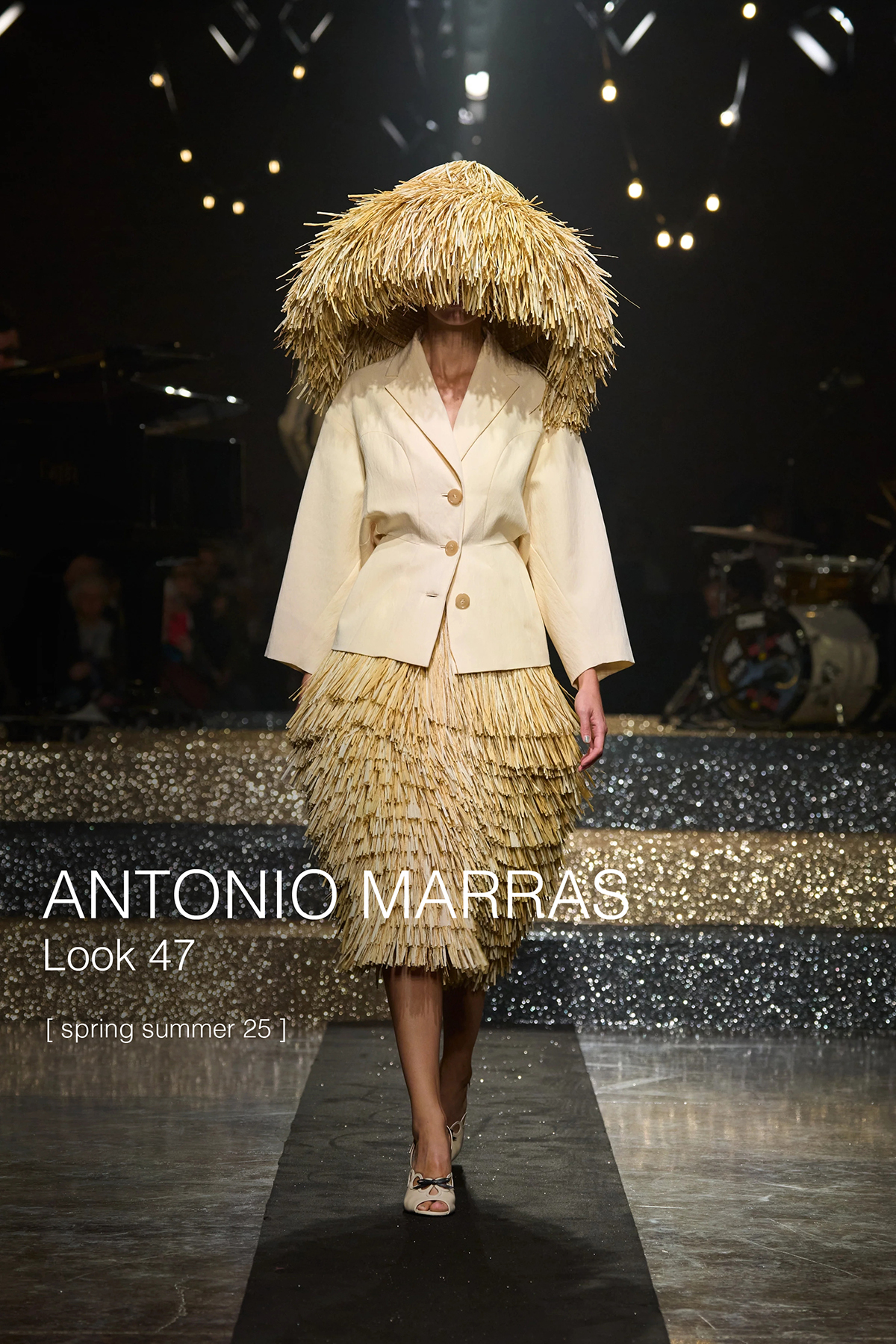

5. Antonio Marras, look number 47

Milan. The risk throughout the entire show is going ethnic. Too many prints, too much romanticism, too much of everything—but then comes this skirt that starts from the hat, a jacket with a cut reminiscent of Christian Dior’s Bar suit. Strips of straw cut to different lengths to create volume. It could be hand-stitched, which would make it haute couture – but these are ready-to-wear clothes, made with textile solutions that allow for reproduction.

6. Del Core, look number 11

Milan. The reference to Prada is clear—yet the monochrome and roughness of the fabric, along with the bourgeois commercial intent, find balance in a dress that, with the right media support—reputation, not numbers—could effectively build Del Core’s identity. We could all recognize a geometric silhouette with the right proportions as belonging to a fashion house that could restore power to Milan Fashion Week: the city needs independent and rising names to stand alongside global brands. This dress finds a sartorial simplicity: it’s an apron with straps, but its proportions could translate into a dress for Babe Paley, photography by Horst.

7. Bottega Veneta, look number 51

Milan. Sometimes a fashion show isn’t the development of a single or even two ideas in a rounded narrative—sometimes, a show is a wardrobe, as we see here with Bottega Veneta. Going through the collection, there’s no groundbreaking design—except for the first pair of culottes, with one ankle exposed and the other not, which we’ll ignore. There are even some missteps—like a macro zebra print. What lingers is the overall impression: balance, a sense of proportion. Matthieu Blazy at Bottega doesn’t need to try too hard: he doesn’t need to impress either. The look we keep is number 51, for men: the silhouette of the shoulders, the width of the trousers, the lapel with a red buttonhole—the fabrics in natural colors, wool, cotton, linen.

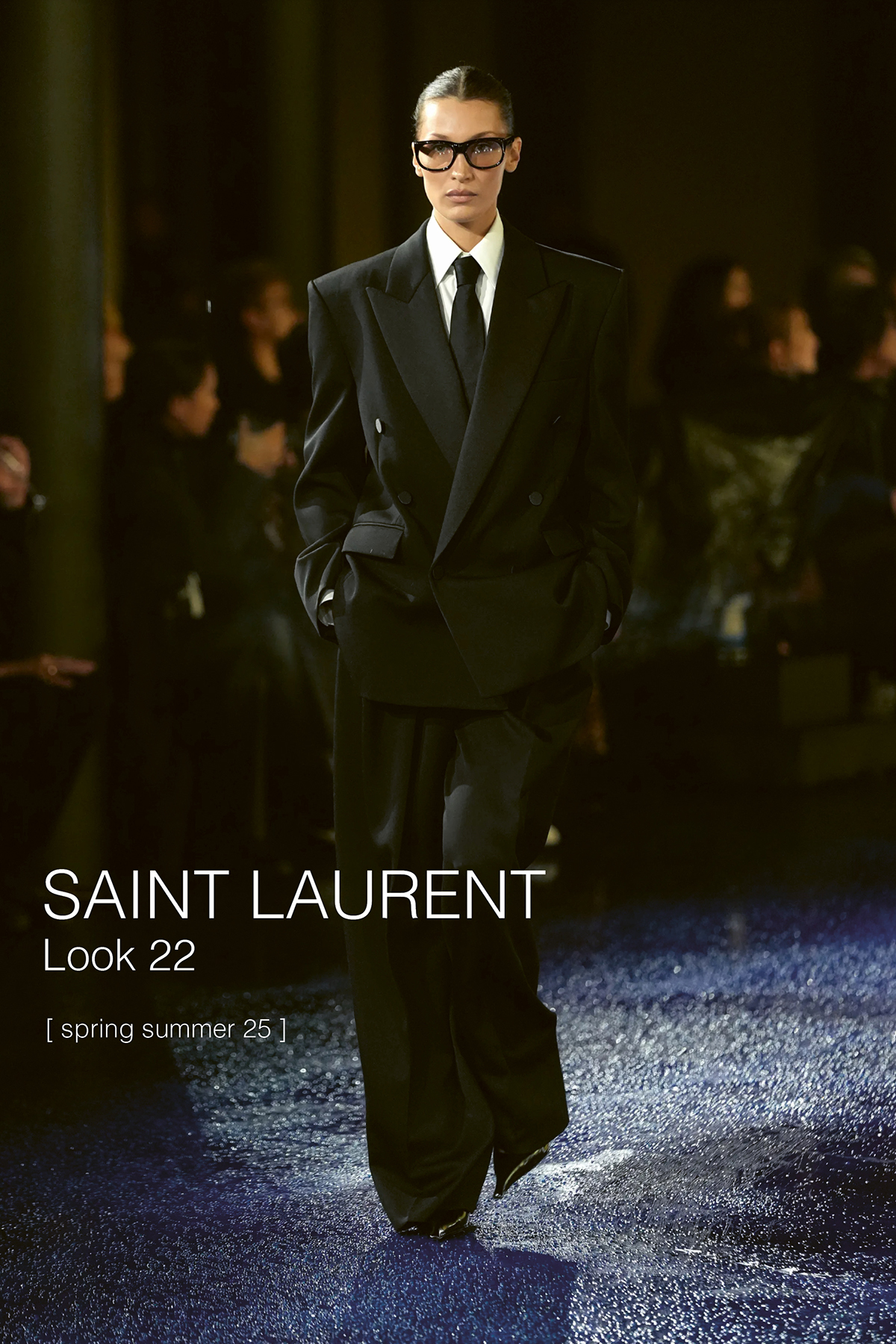

8. Saint Laurent, look number 22

Paris. The rigidity of the 1970s silhouette, with those armor-like shoulders, orthogonal to the body’s axis as if we could all turn into a sketch on paper. Anthony Vaccarello shakes off the image Hedi Slimane created more than a decade ago and solidifies his own identity for Saint Laurent. He does this by reworking the founder’s codes, diving deep into the 1970s, which YSL had so sublimated. We focus on the first half of the show, where each look is more precise than the last. The apex, if we must choose one, is look 22. Here, the risk of turning Mica Arganaraz into a young YSL with glasses and neatly combed hair succeeds in making us smile without descending into sarcasm. We skip the second half of the show: overly colorful, overly shiny, overly worked.

9. Courrèges, look number one (presentation)

Paris. Sometimes, everything is said at the first look—like the opening of a novel. Sartorial design is so simple it feels like it’s always been there, yet it still feels new. The hood, or rather the cape, begins at the shoulder line. A design so self-assured it can reference the photographic volumes of Cristóbal Balenciaga. The rigidity and volume, hopefully achieved through the quality of the leather and not plastic supports (though some plastic is likely). Leather supply chain: a byproduct, yet from the most polluting industry. The luxury sector will soon need transparency and honesty in leather sourcing—but for now, the question is posed without an answer. As the collection progresses, we notice the shoe design: a consistent band from heel to ankle. It aligns with the solidity introduced by the first look.

10. Loewe, look number 52

Paris. The show begins with transparent printed veils on structures playing with old crinolines. Their relevance is hard to gauge: these looks are likely intended for editorial purposes-garments for magazine layouts. Skipping the first three pieces, we reach the fourth look, where trousers are played with through a lateral pleat, an abundance of fabric turning into drapery. These trousers summarize the show and are the standout of the collection. They keep alternate with unnecessary crinolines, which perhaps help, by contrast, to highlight the volumes. Blouses and tunics, like inverted corollas, even in crocodile. The standout look is number 52, where the trousers become a complete outfit.

Final mention: Celine

Hedi Slimane doesn’t do a runway show—he releases a video. The show doesn’t appear on Vogue Runway’s app, the platform where professionals view nearly all shows in real-time. Hedi Slimane doesn’t want to work with Vogue, doesn’t appreciate its editor-in-chief, doesn’t admire Vogue‘s editorial work. There’s a rumor that Hedi Slimane is headed to Chanel. This show seems like a provocation: as if to say, “I’m already doing Chanel, this is my Chanel, I want to do Chanel, if they don’t let me do Chanel, I’ll do it anyway—I am Chanel.” Another rumor: Chanel’s owners want Slimane, but management is against it. Karl Lagerfeld named him his successor. Nothing confirmed—just one certainty: Hedi Slimane is moving on a track different from everyone else’s.