35 years of Galleria Continua: “we’re ordinary people, without powerful families behind us”

Interview with Lorenzo Fiaschi, Maurizio Rigillo, and Mario Cristiani of Galleria Continua on 35 years of activity: short supply chains, slow routes, reuse, and CO₂ in San Gimignano

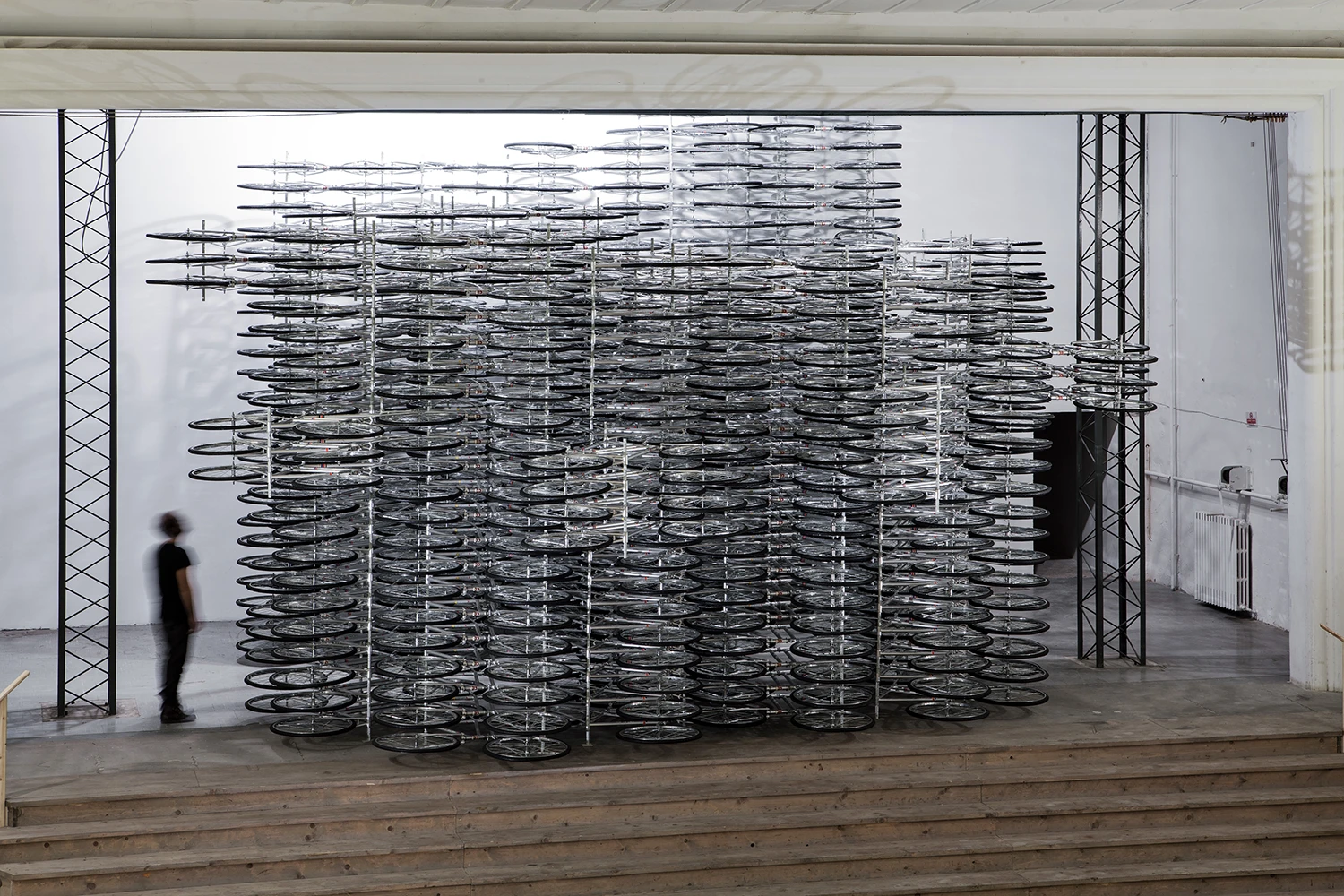

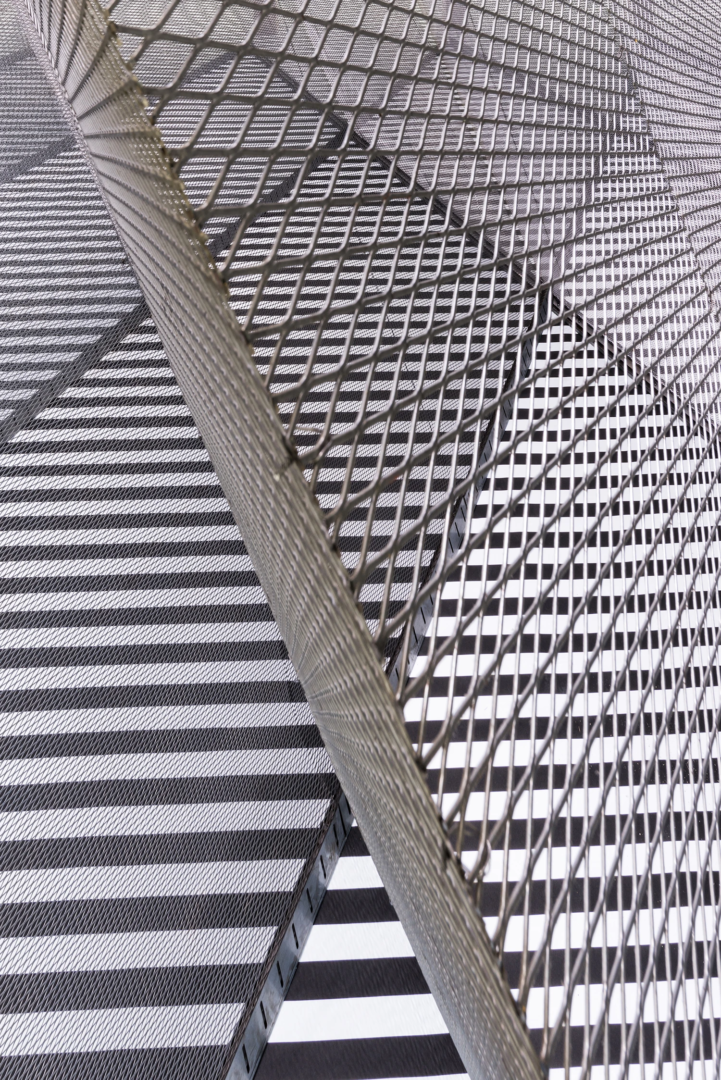

An abandoned cinema in Cuba, two mills in the French countryside, a stadium in São Paulo, and the Burj Al Arab in Dubai: Galleria Continua has turned unlikely places into art spaces, restoring voice and memory to forgotten buildings. The rule is simple yet radical: it’s not the exhibition that imposes itself on the space — the space sets the rules. “Every space has a voice,” says Lorenzo Fiaschi. “The most powerful installations come from listening to what the architecture suggests, rather than forcing a predefined aesthetic.” In San Gimignano, a conversation with the three founders — Lorenzo Fiaschi, Maurizio Rigillo, and Mario Cristiani — celebrating 35 years of Galleria Continua.

Letting the Place Speak: Measure, Roughness, and Living Heritage

Lorenzo Fiaschi explains: “Our spaces carry such strong traces and memories that they can’t be ignored. Memory whispers stories. Respecting the site is at the heart of our work with artists: what seems like a limitation becomes a source of invention. That’s why, over the years, we’ve restored spaces with care for their original nature — the mills in the French countryside were renovated while preserving their historical structure and layers; the 1930s cinema in Havana was brought back to life without losing its identity. That’s the meaning of our name: Galleria Continua — continuity in the story of places through contemporary art.”

Breathing Sustainably: Light, Water, Waste — Everyday Practices

When asked how a venue “breathes” on a typical day — lights, air, water, waste — Maurizio Rigillo replies: “In our daily operations we focus on how spaces are managed. Lighting is LED-based, with low energy consumption and used only during opening hours. We ask the team to turn off lights in exhibition areas and offices when not needed, even during breaks. We’ve begun studying energy use across all venues and storage sites in preparation for solar panels — San Gimignano will be the pilot project, paving the way for energy independence. For heating and cooling, we adapt to the seasons, delaying the use of air conditioning or heating and limiting it as much as possible. Each location has a drinking-water dispenser: everyone refills their own bottle, reducing waste and packaging. In the kitchen, waste is carefully sorted and labeled. Simple, shared gestures that, collectively, reduce consumption and waste.”

Short Supply Chains and CO₂: Local Production, Reuse, and Slow Routes

On how they balance production and transportation, Rigillo continues: “Working with living artists, we prioritize works conceived for the site and produced with local artisans and companies — we avoid moving existing pieces over long distances. Each location has a nearby storage facility: we recover and preserve installations for future re-use. When we ship works to China, we use sea freight instead of air whenever possible. Energy-intensive works are activated only occasionally, on special occasions. For installations, we rely on local crews and reuse wooden crates as long as they remain intact and safe. That’s how we balance artistic needs with responsible management of resources and logistics.”

Associazione Continua as a Political Act: Autonomy, Human Commitment, Public Value

Mario Cristiani recalls: “The Association was born in 1990 together with the gallery. There were about fifteen of us — we three formed the core. Lorenzo was president until 1995, Maurizio the treasurer, I the vice president. With Arte Continua, our goal was to bring the same artistic quality of our history back into public spaces — not open-air museums, but cities and everyday places reimagined through accessible, site-specific works. The name expresses our ambition: to keep the past alive in the present. My question then — and now — remains: what survives of democracy as a sign of individual freedom and social mobility? How can we give small towns a dignified present, in dialogue with their past? In 1989, during the French Revolution bicentennial, I visited the Louvre and saw I.M. Pei’s intervention — it was a revelation: it was possible to engage with history on equal terms. We just had to find the right people.

That’s how Arte all’Arte was born — a replicable model with pairs of curators (one Italian, one international) choosing artists, fully independent from gallery logic. Public artworks remain property of the artists; projects are funded through donations and fundraising. In difficult years, I personally guaranteed the Association’s debts. In ten years we’ve realized 89 projects across the San Gimignano–Siena area, 21 of which were donated to local communities — today their combined value approaches €15 million. Among the latest projects: a Mimmo Paladino exhibition at UMoCA in Colle Val d’Elsa; with Penone, we worked in Piazza della Signoria and at the Uffizi. These choices don’t follow the gallery’s market interests — though sometimes collaborations overlap later, always as a second step. When someone expresses interest in a work, we connect them directly with the artist; donations to the Association are voluntary. In theory, artists or their galleries could reimburse production costs upon sale, but we’ve never required it. After COVID, we restructured with professional advice to make the model more sustainable and avoid past financial issues.”

Public Art: Long-Term Care and Shared Responsibility

Cristiani explains: “We always formalize an agreement — it’s a relationship between people. As president of the Association, I act as guarantor for the artist, ensuring proper maintenance and promotion of the work; if that fails, the piece returns to the artist or their heirs. Usually the Association handles maintenance and alerts the local administration when needed. Post-COVID, we’ve also raised funds for art education so that, over time, citizens and institutions can take care of the donated works themselves.”

Art for Reforestation: Environmental Substance, Not a One-Off

On the Art for Reforestation project — from the auction with Pandolfini to the Bosco delle Neofite in Prato designed with Prof. Stefano Mancuso — Cristiani says: “This second campaign revisits a core idea: the link between public and private within the non-profit sphere can generate social value if everyone gives something up and mutual respect is maintained. With the help of artist friends — who donated works sold at dinners offered by a restaurateur, so that no funds were diverted — and with further donations, we signed an agreement with the City of Prato for a €150,000 donation: Prof. Mancuso’s consultancy, reclamation of the area in front of public housing, and maintenance of the Bosco delle Neofite as city property. We also funded information totems beside the trees, telling the story of the species and the artists involved. Our contribution allowed former councilor Barberis to add another €150,000 for further urban reforestation. We’ll continue the campaign in Prato after the elections and are in talks with other municipalities. That connection is vital: oxygen for the body and for the mind — and vice versa.”

ITALICS: A Widespread Heritage That Lasts Beyond the Event

FJC: How does ITALICS’ network work to ensure it’s not just about the event? What concrete impact do you bring to the territory?

Lorenzo Fiaschi: “ITALICS was born from a shared desire to tell the story of and give value to Italy’s lesser-known territories through art — places outside the usual cultural and tourist centers. The idea is to take root in these places, working year-round with local partners: administrations, shop owners, artisans, restaurateurs, schools, and citizens who, in each edition, have opened their spaces and homes to host Panorama. It’s an event that generates networks, relationships, and long-term returns that extend beyond the occasion itself. Just look at Procida, which became Italian Capital of Culture the following year, and L’Aquila, which will hold that title in 2026. Art, with its power to unite, makes all of this possible.”

Galleria Continua: Access and Human Mediation — Opening Thresholds, Not Filters

FJC: The St. Regis Rome calls for a certain type of audience, while San Gimignano or Les Moulins attract another. How do you prevent the context from “filtering” access? What’s the most decisive action you’ve taken to keep that threshold truly open?

Lorenzo Fiaschi: “The context is crucial — it shapes what happens, who enters, what they expect, and what they allow themselves to experience. Each location activates a different imaginary, and with it, a different public. That’s why we aim to be where we’re least expected, to reach a broad, diverse audience and build bridges between places and communities. Our goal is for no venue to become a barrier. Every space, however specific, must remain open. The answer lies in programming, but also in the architecture of hospitality: extended opening hours, free admission, human mediation, and side activities for those approaching art for the first time. We’ve developed educational programs and school visits — in Rome, Cuba, and Les Moulins — to involve children and young people in creative processes.

The most radical choice has been to distribute our presence across highly diverse locations, opening venues in non-canonical contexts: a medieval village, two mills in the French countryside, iconic hotels like the Grand Hotel Rome created by César Ritz (now the St. Regis) with the city’s first public ballroom, the Burj Al Arab in Dubai, a stadium such as the Pacaembu in São Paulo, and a 1930s cinema in Cuba. This decentralization both forces and allows us to reinvent the experience, to move beyond the rhetoric of the ‘right audience’ and open the threshold even to those who didn’t know they were looking for it.

In Havana, the gallery has become a crossroads of meetings and life — human, cultural, and creative — even before artistic. Exhibitions, festivals, workshops, and open dialogues with the community all converge there. Charlas Continuas, open talks with artists, critics, and curators, and CRE-ARTE en Continua, developed by Michelangelo Pistoletto with our team, have generated over a hundred workshops for children, teenagers, and the elderly, promoting sustainability, creativity, and inclusion. In France, at Les Moulins, school visits transform the site into a hands-on laboratory of artistic discovery for the youth of Seine-et-Marne and the wider Île-de-France region, beyond the institutional routes of the capital.”

Galleria Continua and Young Professionals: Entry, Growth, and Responsibility

FJC: If a young professional knocks — a cultural mediator, host, technician, or junior curator — what’s the real entry point? What do you promise (training, time, responsibility), and what do you ask in return? How does one grow with you over 12–24 months?

Maurizio Rigillo: “For young people, the entry point is the curricular internship, set up through agreements with universities and with a modest stipend. It’s not a rigid path: interns are exposed to all aspects of gallery work — cultural mediation, visitor reception, technical setup, and organization — so they can discover personal inclinations and shape their direction.

Our team is made up of professionals with years of experience in different fields, and they guide the younger members. We offer on-the-job training, dedicated time, and gradually increasing responsibility based on maturity. In return, we ask for versatility, flexibility, commitment, and a strong sense of responsibility. It’s a path from exploration to consolidation — moving toward a more defined role and an increasingly autonomous contribution to the gallery’s life.”

Young Artists: When Galleria Continua Says No

FJC: When it comes to young artists, what kind of “no” do you say to protect their development? Has there been a time when you slowed someone down because things were happening “too fast,” and that artist later found success elsewhere?

Maurizio Rigillo: “With young artists, we protect their path and growth. Working with us is an opportunity, but if it comes too early, it can become overwhelming. From the beginning, we grew alongside artists our own age — that’s why we introduce new talents cautiously, only once they’ve found balance and consolidated their language.

We’re also guided by a principle Luciano Pistoi once summed up: ‘the first act of criticism is buying.’ As private individuals, we’ve supported young artists by purchasing works or recommending contacts in academic or residency contexts that regularly ask us for names.

Since the very beginning, I’ve been involved in the project Una Boccata d’Arte with Marina Nissim and the Fondazione Elpis, which commissions under-35 artists to create projects in Italian villages every year. We closely followed the first editions and, even though it’s now run entirely by the foundation, we continue to share our experience. It’s a valuable tool for supporting growth — respecting timing and fostering a genuine connection with the local context.”

Courage as a Method: Choices Beyond the Business Plan

FJC: From China to Tuscany, from Paris to São Paulo: what is one mistake of the art system that you no longer want to repeat — and how has that translated into a concrete decision about programming, travel, or installations?

Lorenzo Fiaschi: “Rather than avoiding mistakes, what matters most to us is staying true to who we are — guided by courage and openness to the world, without letting a business plan or purely commercial strategy dictate our path. We were the first foreign gallery in China and Cuba, and the first contemporary art space in the countryside with 30,000 square meters of exhibition area. Our choice is to follow intuition, passion, the artists and their projects — with the freedom that has defined us since the beginning.”

Access, Merit, Social Value: A Measurable Human Commitment

FJC: In an art system that is often opaque, selective, and sometimes out of step with the present — in a world marked by ongoing wars and by career paths that at times advance through privilege more than merit — what public and ongoing commitment are you willing to make, as an international gallery, to place access, merit, and social usefulness at the center of your work, and to measure over time your ability to change yourselves along with the system?

Mario Cristiani: “Our experience weaves together the actions and passions of three people with different voices but a shared drive. We want what we’ve done — and what we continue to do — to serve as encouragement for others: to come together when young, to use knowledge and skills without taking for granted the obstacles that so often discourage initiative. We’re ordinary people, without powerful families behind us; still, our families supported us through difficult years.

Our commitment is to never give in to circumstances, to keep our eyes open to what’s happening in the world, to welcome what artists place before us — in thought and in action. Each of us does it in our own way, finding the points of connection that allow us to act together: day after day, year after year, with artists, staff, collectors, and all those who care about us, the gallery, and the association.”

Galleria Continua

Galleria Continua was founded in 1990 by Mario Cristiani, Lorenzo Fiaschi, and Maurizio Rigillo, with the idea of giving continuity to contemporary art in a landscape shaped by history. Established in a former cinema, the gallery took root in an unexpected place — San Gimignano.

In 2004, it opened in Beijing, presenting Western artists in a context where they were still little known. In 2007 came Les Moulins, in the French countryside, a site dedicated to large-scale projects. In 2015, the gallery opened in Havana.

In 2020, marking its 30th anniversary, Galleria Continua expanded to Rome and São Paulo, within the Pacaembu sports complex. At the beginning of 2021, it opened a new space in Paris, in the Marais, and later that same year at the Burj Al Arab Jumeirah in Dubai. In 2024, a third French location opened in Matignon, the epicenter of Paris’s art market.

In San Gimignano, current exhibitions include Yoan Capote: Ruido Blanco and Chen Zhen: Un Village sans frontières, both on view until January 7, 2026. Completing the program is Alicja Kwade: Vestigia, open until November 20, 2025.