Homo Faber: much wonder and a bit confusion

From the Goose Game to the Globes for the Sun King, passing through a child’s playroom, phosphorescent plastics, and paints: Homo Faber 2024 on the Island of San Giorgio in Venice

A visit to Homo Faber 2024: The Goose Game

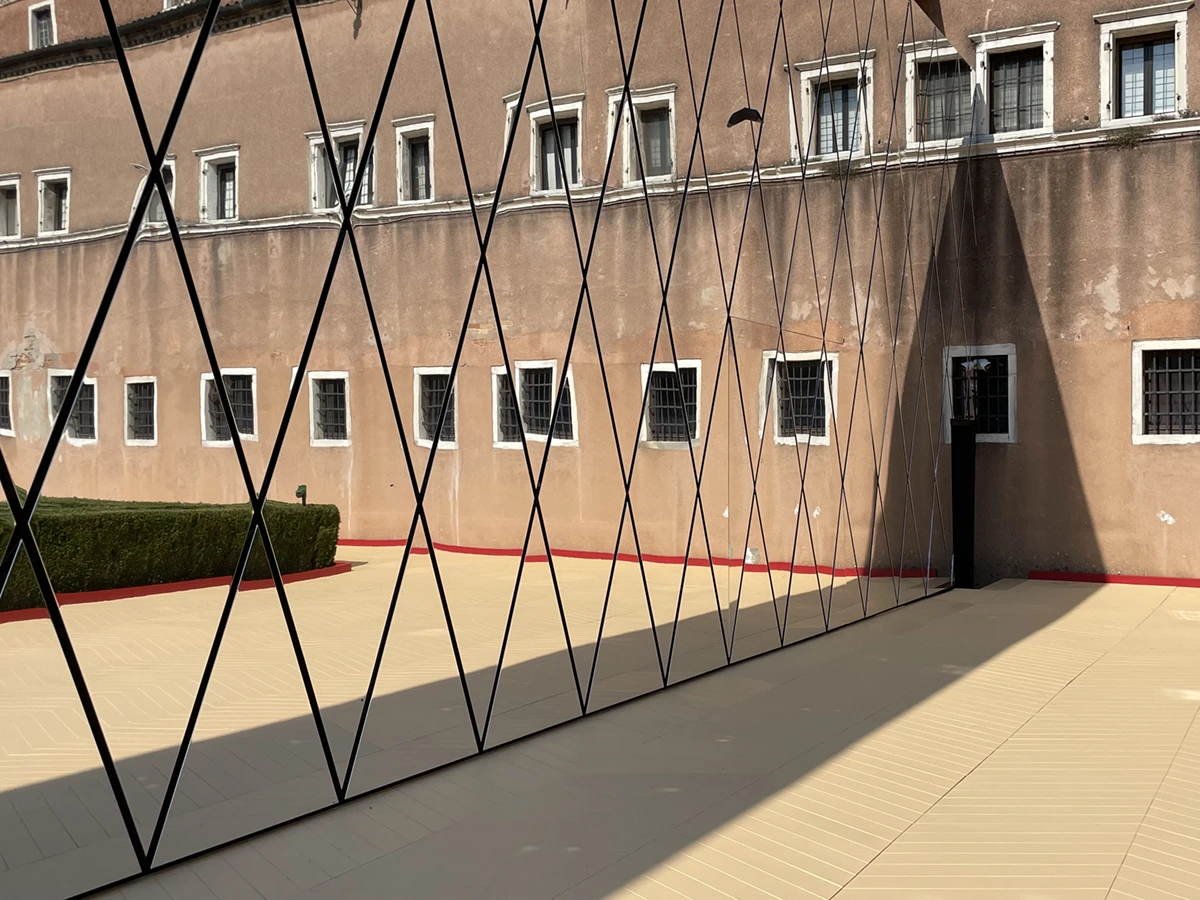

Upon entering for a visit to Homo Faber 2024, you walk on the side of a hedge maze, that one who was inspired by Jorge Luis Borges and built in 2011. Every maze has more than one exit or none – however, what matters in every maze is getting lost. In the first cloister of the Monastery of San Giorgio, the maze transforms into a Goose Game board.

The Goose Game has existed since the 1500s. In 1580, the Grand Duke of Tuscany Francesco I de Medici gave a game board to Philip II, King of Spain. In the traditional version, every nine spaces feature a drawing of a goose: we’ve all played it—throw the dice and count the spaces. Roll a 9 on the first throw, land on a goose, and move another 9 spaces. On square 42, you pay duty, and you return to 39. If you land on square 58, the skeleton square, you go back to the start. Victory lies at square 63, a number achieved by multiplying 9 by 7. You don’t simply pass it as a finish line; you must land on it, like descending from a hot air balloon on the precise spot.

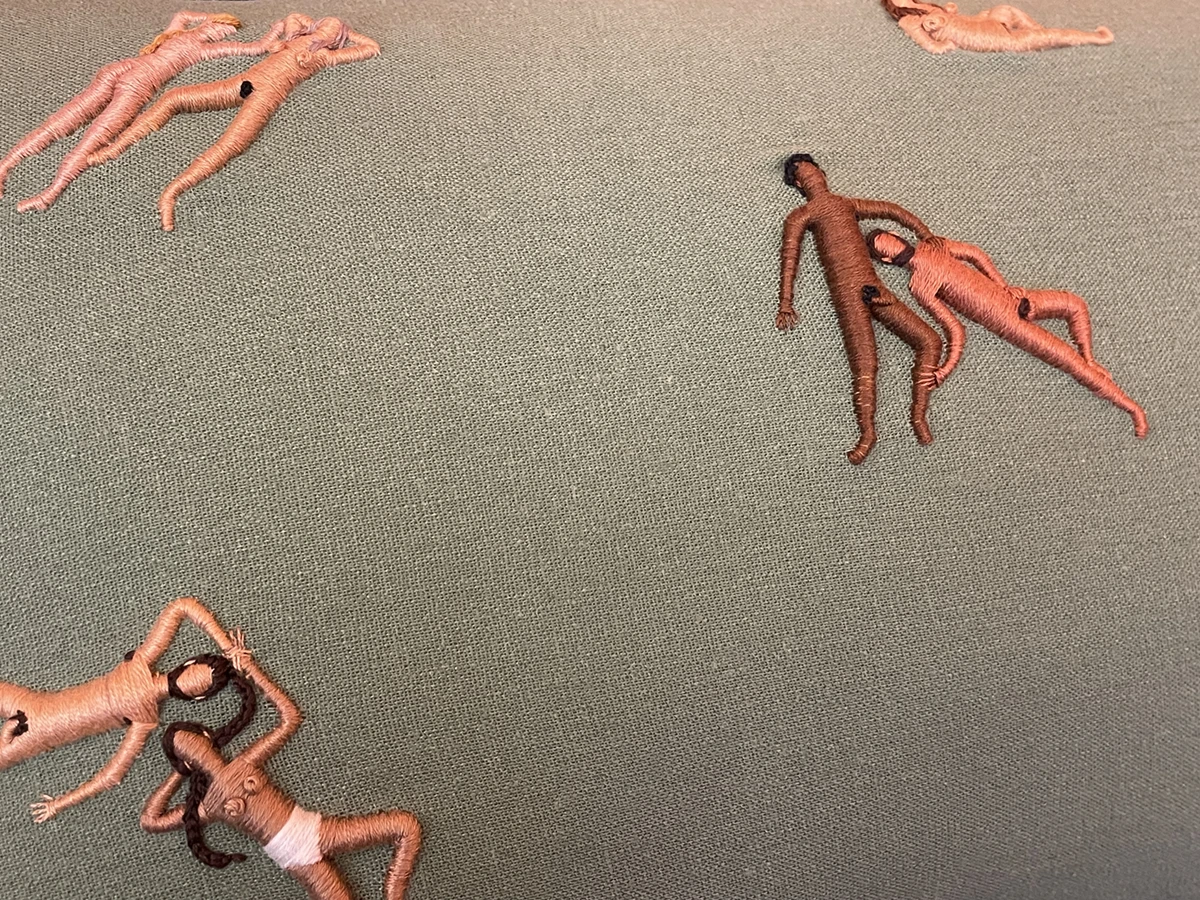

Homo Faber 2024, Island of San Giorgio, Venice. The Monastery portico is the path for the Goose Game board. There are 60 embroidered panels on the fabric instead of 63. Artisans from everywhere in the world, from Rwanda to Mexico, have used traditional techniques to create the panels: they have realized embroidered and jacquard textiles; they have employed cotton, silk, and metallic threads, but also synthetic fibers for phosphorescent colors.

Homo Faber 2024: The Journey of Life, curated by the Michelangelo Foundation, with artistic direction by Luca Guadagnino and Nicola Rosmarini

The Homo Faber 2024 exhibition is entitled The Journey of Life—a title that suggests simplicity. The concept is provided by Hanneli Rupert, Vice President of the Michelangelo Foundation for Creativity and Craftsmanship. This is an initiative driven by her father Johann Rupert and Franco Cologni. Mr. Rupert is the president of the Richemont group, which includes Cartier; Mr. Cologni developed the Cartier and Richemont business in Italy. Homo Faber is a biennial exhibition curated by the Michelangelo Foundation. For the 2024 edition, the artistic direction was entrusted to Luca Guadagnino, a director who here takes on the intellectual role of architect, set designer, and creator, alongside architect Nicola Rosmarini.

Each phase of the exhibition is a step of our life journey. Using the property of the absurd, the maze might symbolize the maternal womb—the only place we have visited so far that is not a labyrinth. We lived our childhood, and the Goose Game aimed to teach us as young children that the sooner we understand how unpredictable life can be, the better. During adolescence, the games multiplied in our bedroom, basking in the afternoon sun, with clouds on the sheets of the blue, clean bed and legs tired from the walk our mother forced us to take to the City Gardens right after the afternoon nap. It’s five o’clock, and we can pull out our toys from the closet and all the shelves. Here at Homo Faber, artisans are still playing with us.

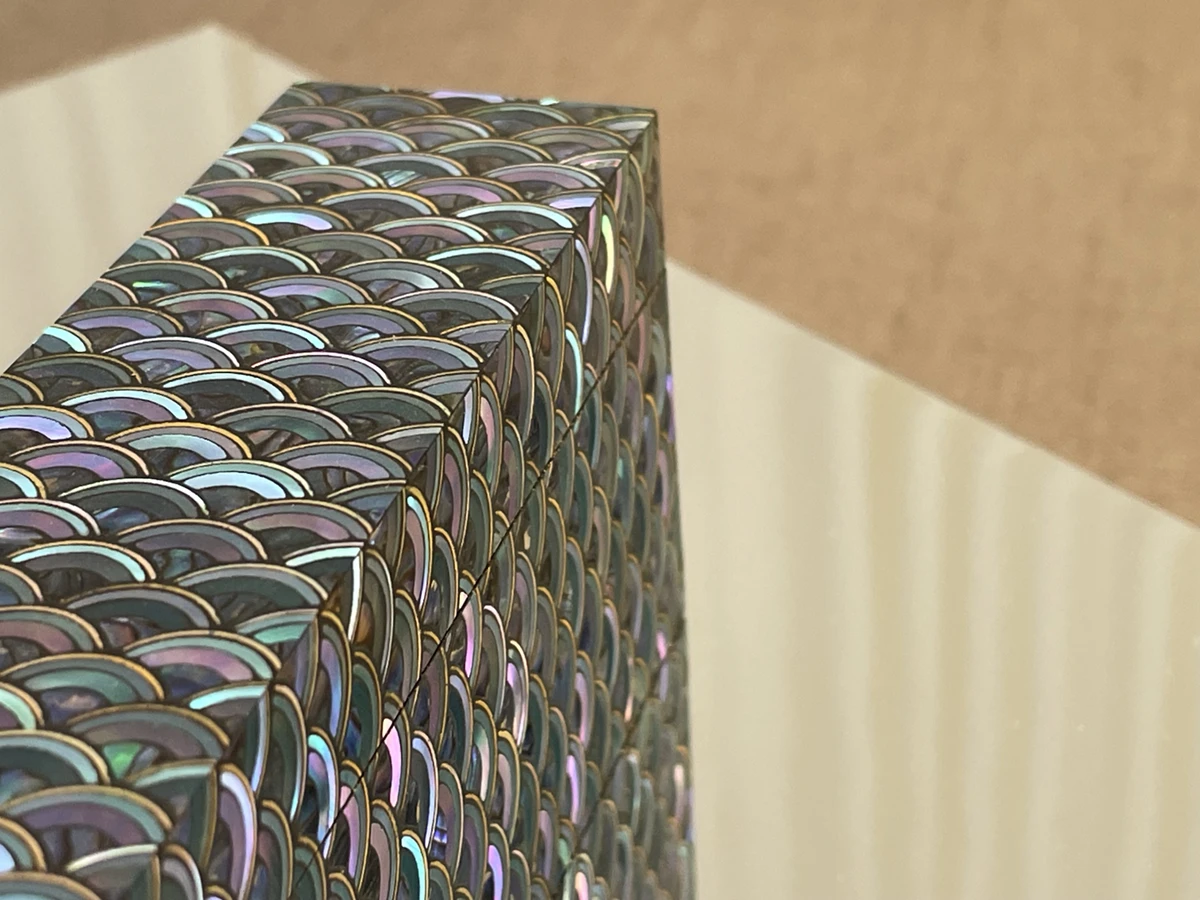

Homo Faber 2024: The Playroom

The circus animals that we must push onto Noah’s Ark’s ramp are now amorphous shapes, with triple heads, either tiny or gigantic. They are made of wood, plastic, polyurethane, and foam rubber—sometimes slimy, sometimes hairy. There is a backgammon set, which has been turned into mother-of-pearl by the Blue Fairy. The sharks are inflatables. The pinball machine is an inlaid wooden piece. The aviary is a Versailles pavilion. The Dollhouse is a delirium by Renzo Mongiardino (properly thinking about it, Renzo Mongiardino spent his entire life designing dollhouses). The mice are giant acrobats. The wordsmith is a matrix of dentures and severed tongues. Glass cars from Murano race on rollercoasters. In an instant, our playground is a mess.

Homo Faber: The Globes of Leonardo Frigo According to Vincenzo Coronelli’s Book Epitome Cosmografica

Homo Faber is an exhibition that gathers and presents human-made objects. Among these, some would be worthy of a dedicated book, given the extent of the effort involved. Leonardo Frigo is a globe-maker who revived Vincenzo Coronelli’s techniques – the friar active in the second half of the 17th century. His globes were commissioned by the Sun King and the Duke of Parma. Leonardo Frigo recounts how, after years of research, he managed to acquire Coronelli’s book Epitome Cosmografica, a text bordering on the legendary that describes the art of globe-making: the wooden supporting structure to hold a meter-wide sphere, paper fabrication, the printing plates. Leonardo Frigo had been seeking this text in auctions, but he couldn’t afford it when the bidding exceeded two hundred thousand pounds. Then, while wandering through flea markets in London and Paris, he found a copy on a stall. It could have been a fake reproduction but, as he flipped through the pages with the expertise of a typographical scholar, he recognized the original edition. He kept his composure, and he bought it for a few dozen pounds.

The two Coronelli Globes made for the Sun King reach almost four meters in diameter. They were commissioned on behalf of the sovereign by his then-ambassador to Rome, Cardinal d’Estrées, and are now preserved and exhibited at the Mitterrand site of the National Library of France. At the end of the 17th century, these globes became so famous that they sparked a fever of demand. Friar Coronelli became a celebrity in aristocratic and academic circles. The globes depicted the known world, where California was shown as an island, where the birthplace of an heir to a duke was more prominent than a mountain range, where every corner of the planet was represented in a fantastical way. When Napoleon conquered Venice, he removed the Golden Lions and The Marriage at Cana from the refectory of San Giorgio, where the Homo Faber exhibition is now held. He also requested the two Coronelli globes from the Convent of Sant’Agostino. The nobleman Giovanni Vertova hidden them – thanks to him, today these two globes are housed in the Civic Library of Bergamo instead of in a hall at the Trianon.

The larch wood from the Asiago plateau and resins mixed with flour

By meticulously studying each page of Coronelli’s Epitome Cosmografica, which he fortuitously found and purchased, Leonardo Frigo was able to follow its instructions and recommendations, rediscovering the art of constructing a paper globe. The materials are the same as those used in the 17th century, along with traditional artisanal techniques. The wood, like all the ancient wood of Venice, comes from the Asiago plateau, a larch tree. Similarly, the resin, which is collected by making the larch weep, is mixed with flour to create glue. For the paper, Frigo went to Fabriano, where he and a technician dedicated to the craft built a special frame to process the same cellulose mixture used in the past, which the book describes in detail, down to the watermark with almost microscopic precision. The paper must be capable of curving to fit the globe, accounting for shrinkage due to the glue’s moisture and tension during placement and drying.

At Homo Faber, in a room dedicated to the journey as a phase of life, Leonardo Frigo showcases his ongoing work on a globe almost two meters in diameter, commissioned by an English client. The commission involves the depiction of Dante’s world, not our current universe. In addition to the entrance to Hell, Mount Purgatory will also be included in the geography. He will create three copies—one for the client who commissioned it, one for sale at a value of 300,000 euros, and one to be sold to raise funds for charity. The entire process will take two and a half years to complete. We can now see the fully prepared sphere covered in paper. On a table nearby are copper plates, engraved for typographic perfection, with each design being first printed and then hand colored. On the wall hang some segments that represent Earth’s latitudes. The globe is placed on a wooden base and will be finished when more wooden circles are added to depict the celestial layers, the planetary orbits leading to Paradise. Mount Purgatory will be a three-dimensional brass sculpture.

Expounding Leonardo Frigo’s work helps illustrate how much detail Homo Faber attempts to convey to the public and how much depth it requires. The criticism is about the overwhelming quantity of stories, the density of the exhibition, and the exaggeration of the collection. This sometimes unfortunately resembles a Parisian flea market. This is not to question its value (perhaps others like Leonardo Frigo will find relics here that will change their lives), but Homo Faber, like elsewhere, should adhere to the principle of less is more. Even the exhibition catalog struggles to feature everyone— our dear Leonardo Frigo, for example, is not included.

Homo Faber and life stages: captions via QR codes

The Homo Faber exhibition follows the phases of life: childhood and adolescence with their games, celebration, courtship and love, the journey mentioned above, heritage, dreams, and even the afterlife. As visitors progress, the countless objects displayed are only accompanied by a QR code for captions. Accessing the information becomes difficult and lengthy. Imagine a crowd of visitors staring at their phones like robotic clones, reading the captions for the objects before them. It would have been better to include basic captions for each object in English. Printed captions could have enhanced the human, not digital, experience of the visit.

Wonder and the Concept of Craftcore

Craftsmanship means manual work, with no — or limited — support from motorized machinery; nevertheless, it delivers unique pieces or limited series. The concept of a craft core begins with a technical skill activated by a local district or a short supply chain. In simpler terms, craftcore means that wonder is born from the available technique and not the other way around – it means, when wonder is the idea, and one must invent a way to realize it. The concept of craftcore should be emphasized in an exhibition like Homo Faber. This is done with the invitation to use local and traditional materials—solid wood, glass, ceramics, natural fibers—and to avoid plastic, chemical resins, acrylic threads for phosphorescent embroidery, toxic paints, and indestructible polyurethanes. The craftsmanship showcased in Venice should be part of the global cultural conversation on a production that knows how to choose positive supply chains for the impact of their trace—both socially, as is certainly confirmed at Homo Faber, and environmentally, which perhaps Homo Faber overlooks.

On the one hand, we could consider that artisans, by definition, produce fewer pieces and thus do not need to worry about waste, residues, and emissions from their artistic work, as the quantities are so small as to be negligible. On the other hand, we are in an exhibition that must convey a message of research, perspective, critique, and innovation. Without this message, there is a risk that the exhibition will settle for the compliment of a long line of spectators in front of the ticket office.

Carlo Mazzoni