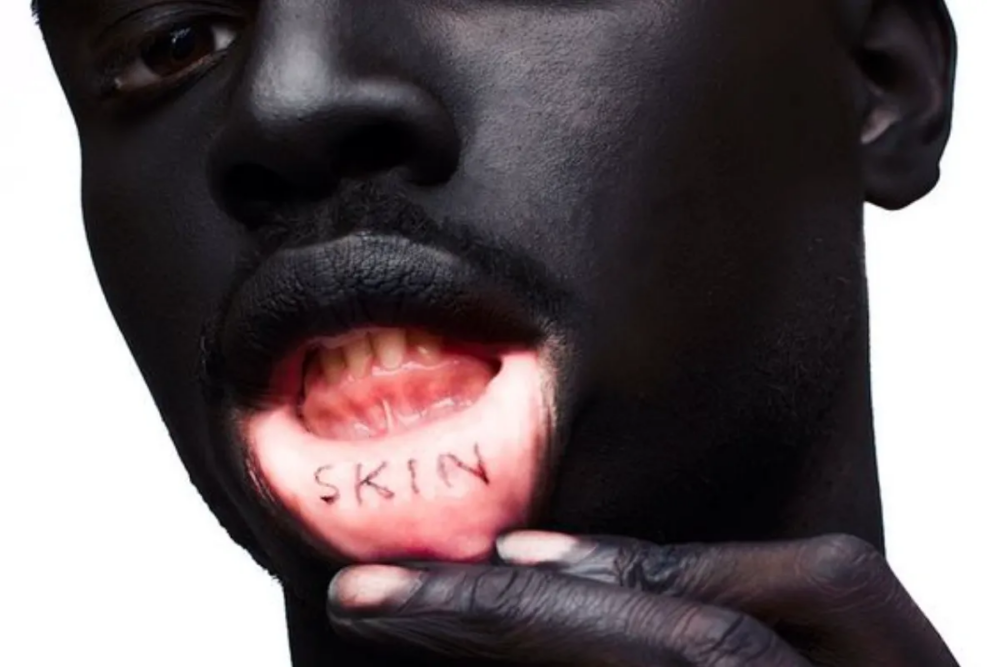

Jean Cocteau’s drawings: explicit sexuality – It is all about poetry

For Cocteau, it was all poetry: a drawing blended with words, Jean Marais the lover and actor in Orpheus, his friendship with Peggy Guggenheim, a relationship with Natalie Paley, the Cartier sword – and opium

Cocteau, the Well-Connected Man, the Renaissance Man, the Man of Many Individuals

Friends, lovers, acquaintances: Cocteau was well-connected – in French, the term branché is used – both in artistic circles and in high society. As a young man, he was the frivolous prince of symbolist poetry. He made his way through Montparnasse circles, and in 1916 he sketched a portrait of Picasso sitting at Café de La Rotonde. The following spring, he was in Rome for the rehearsals of Diaghilev’s Parade: Massine’s choreography, Leon Bakst’s scenography – Picasso’s costumes. Cocteau lived in a world where questions weren’t asked, where there was still a price to pay if you wanted to be openly sexual. A graphic artist, muralist, fashion, jewelry and textile designer, filmmaker. In a photograph by Philippe Halsman, Cocteau is portrayed like a sort of Shiva, a six-armed juggler holding a pen, a brush, scissors, a book, and a cigarette. Perhaps a Renaissance man, mastering so many arts to express himself and mark the time he lived in. Some thought he lacked a single identity, that his versatility led to mere dabbling: “He never let himself go,” Jacques Porel wrote about him, “because too many individuals were within a single man.”

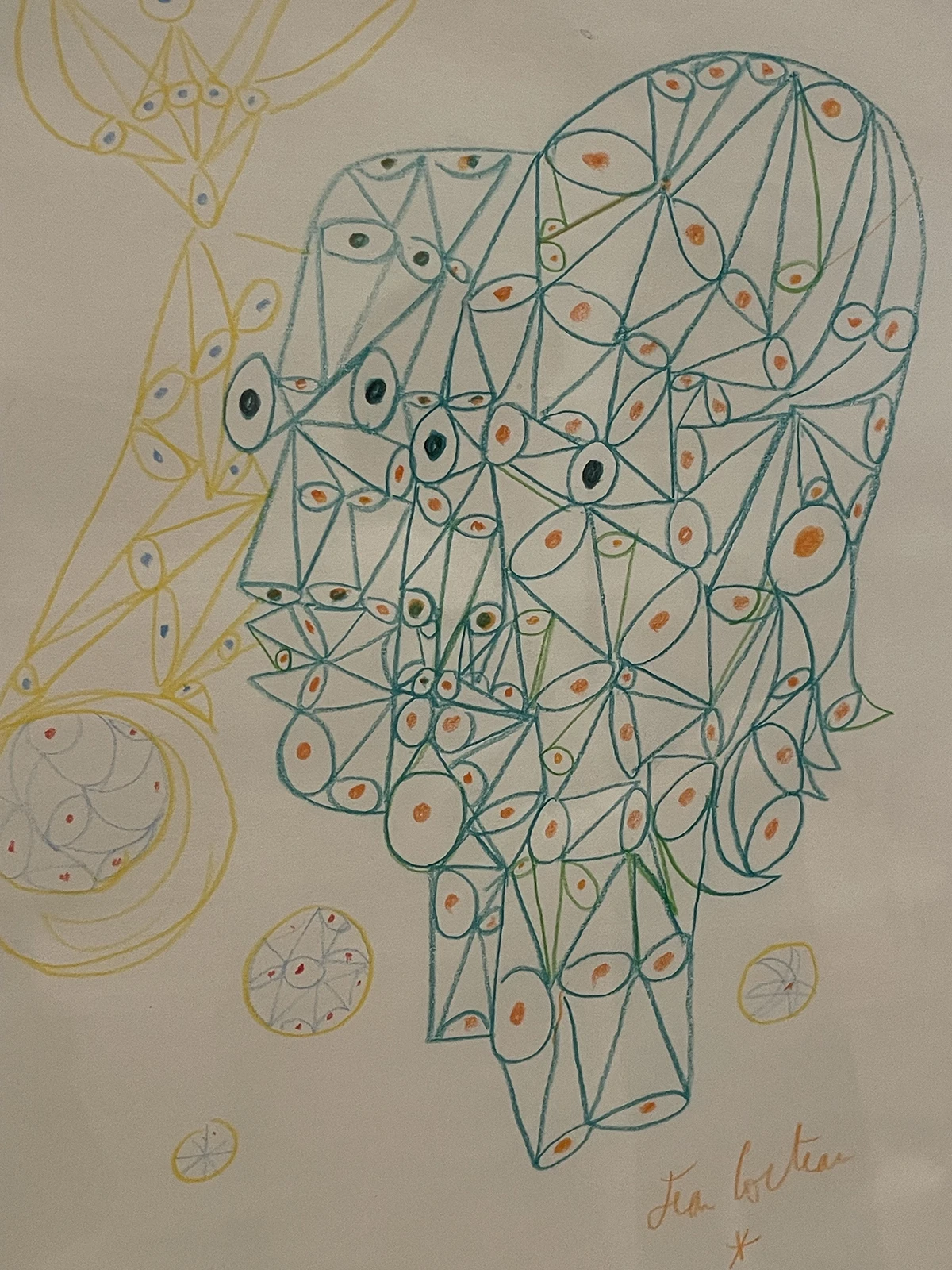

Cocteau’s Graphic Lines: From a Utopian Dialogue with Mies van der Rohe to Orpheus – and the Coincidence with the Kaos Series

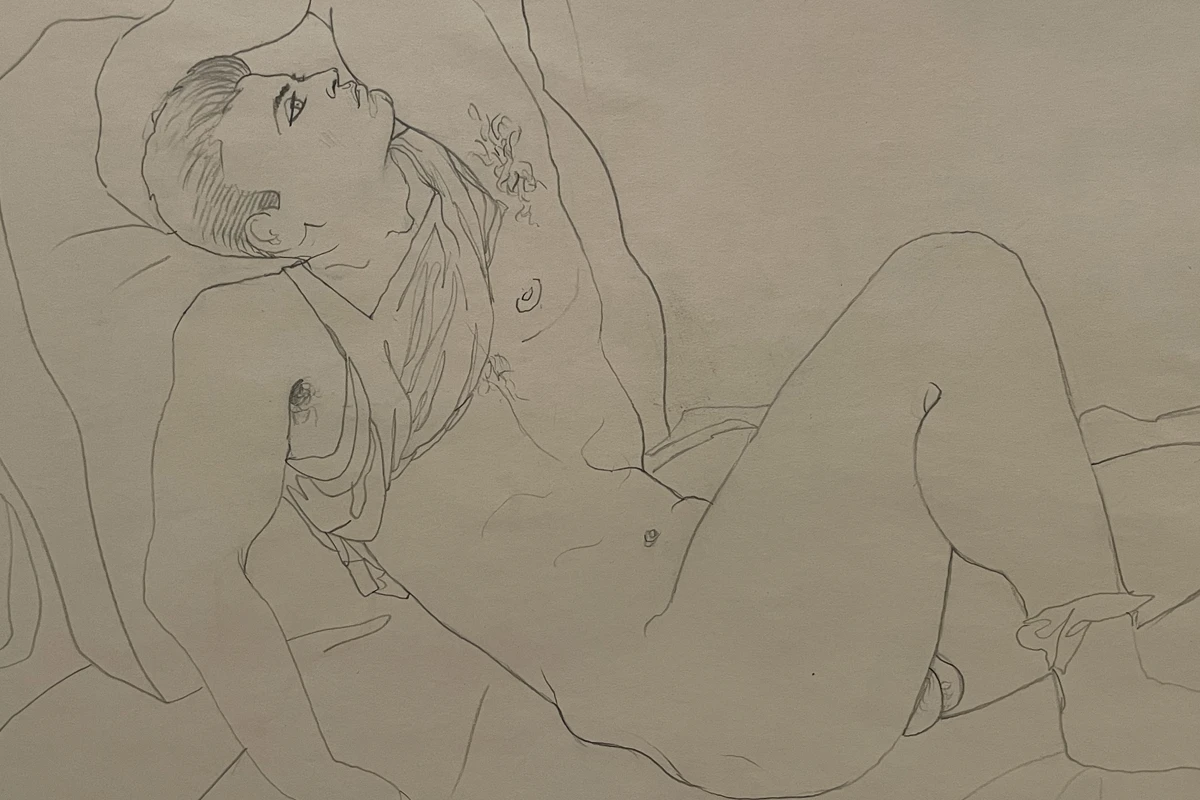

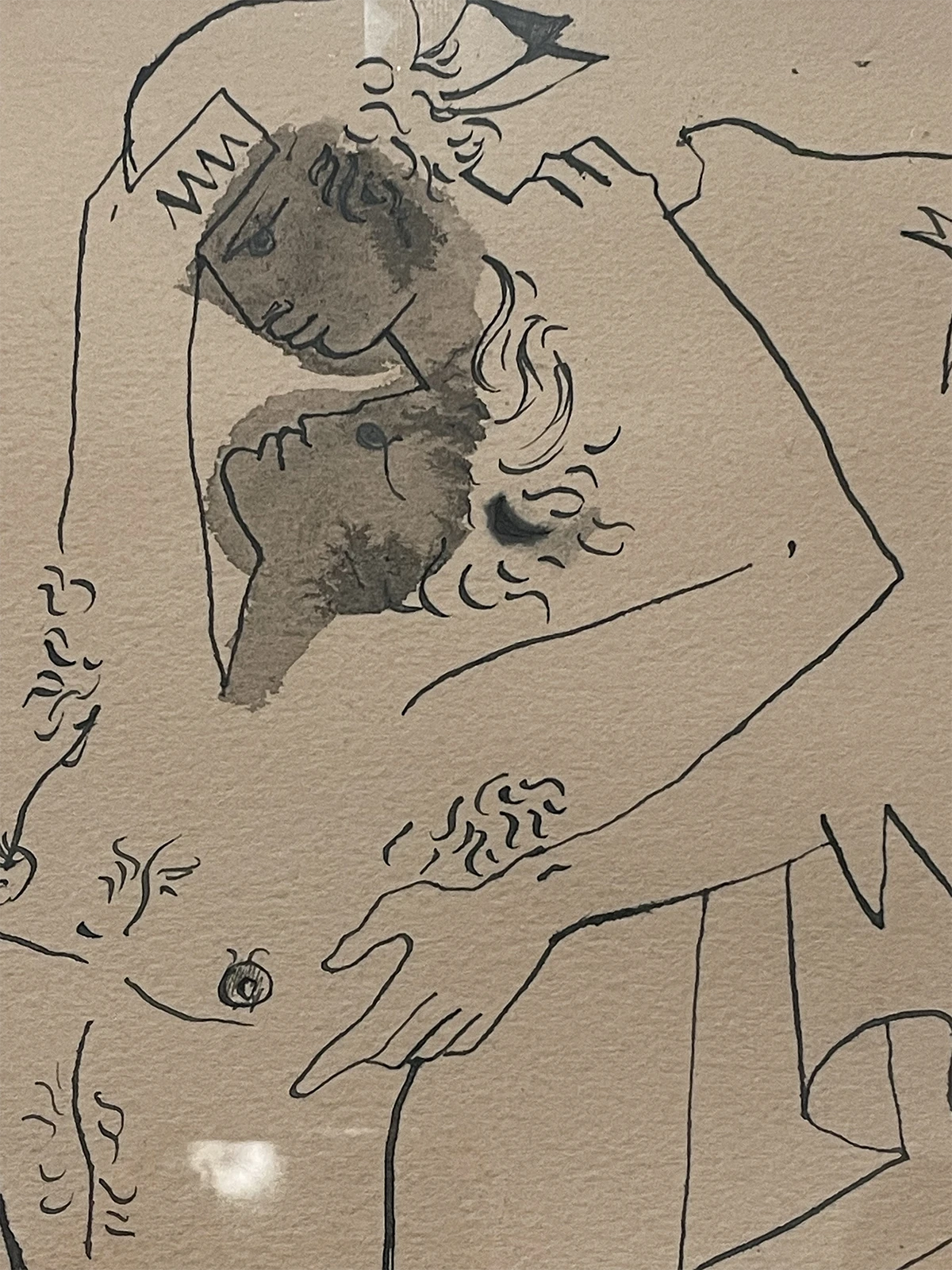

Some, like me as I write, become obsessed with Cocteau’s graphic lines: a few strokes, two intertwined faces, a devil or an angel, two lovers or two children. A lyre or a moon, lips, a nose that could also be Mies van der Rohe architecture, so boundless was his curiosity for all that was impulse or connection or avant-garde. Despite being nearly contemporaries and living almost at the same time, Cocteau and van der Rohe did not have any significant dialogue. The logic that reduced every complexity to a line, the nearly mathematical relationship between poetry and steel, is an imaginary conversation between the two, for which I take the liberty.

Recently, Netflix released a series titled Kaos, starring Jeff Goldblum as Zeus, an actor who bears a vague yet precise resemblance to Jean Cocteau. The series begins with the story we know: Orpheus loses his beloved and ventures into the underworld to find her. Similarly, the exhibition in Venice at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, La Rivincita del Giocoliere, began with a frame from Cocteau’s 1950 film Orpheus. Throughout much of his work, Cocteau drew upon classical iconography: temples, colonnades, ancient statues, and heroic busts for the nude male body, when male carnality was referred to as friendship. For Cocteau, Orpheus is the favored hero, his avatar.

Jean Marais, Cocteau’s Lover and Actor in Orpheus – Poetry, Sex, and Love, Gay Pornography

In the film Orpheus, Jean Marais plays the lead – the actor was Cocteau’s companion for ten years and, according to some rumors, one of Umberto II of Savoy’s lovers. Jean Marais passes through a mirror that changes from a solid plane into a liquid layer. The image moves, like in a dream – a male silhouette becomes androgynous, the virile member grows to unexpected dimensions. We are Les Enfants Terribles, the 1929 novel, poets who do not draw but deconstruct words. Cocteau used the term poetry to describe all his work: when he drew by blending letters and graphics, when he wrote novels, scripts, newspaper articles, or essays, when he directed a film: for Cocteau, everything was simply and always poetry. He had the habit, perhaps the indulgence, of writing on the front pages of books – not only his own when a dedication was appropriate, but on any book, leaving messages of sex or love.

In 1928, he released Le Livre Blanc, a text he chose not to sign or illustrate, which the publisher presented as follows: We publish this work because the talent it reveals surpasses indecency, and because it embodies a kind of morality that prevents an honest person from considering it among libertine books. This timidity would fade twenty years later when, in 1947, he illustrated Querelle de Brest, Jean Genet’s novel, drawing sailors in overly tight, short shirts with overly large members, ready for any carnal encounter in the name of unrestrained sex. Cocteau became a collaborator for bodybuilder magazines published in California, early expressions of gay pornography, where he scribbled pubic hair on too-manicured genitals.

Cocteau and Surrealism, André Breton’s Homophobia, Peggy Guggenheim

In the 1930s, Cocteau approached the Surrealist group but never joined it, as its founder, André Breton, an openly homophobic figure, did not accept him: Breton was repelled by male homosexuality, disdained Cocteau, and did his best to keep him away from the movement he led. For Cocteau, art was an erotic practice. Hands often appear in his drawings, both as the hands of an artist and the hands of a fornicator, rummaging and caressing private parts. Cocteau stains, rubs, the paper sheet, as if wanting to break the virginity of the blank page, smudging it. We are still far from the Stonewall riots on that night of June 28, 1969, in New York – so Cocteau never made a clear formal declaration of his homosexuality during his lifetime. He simply didn’t hide. He didn’t conceal his lovers and wasn’t ashamed of his friends, whether in bed or in sex, nor did he hide his attraction to the male body in his works and poetry – only rarely did he pose as heterosexual. The collaborationist right scorned the couple of men – degenerates, corruptors of youth, clowns, and fools – in the name of tradition and family. They were in a restaurant in Paris – Jean Marais reacted: he spat in the face of the most offensive critic, Alain Laubreaux, a Nazi sympathizer, and punched him. Simone de Beauvoir reported the incident: “Laubreaux grossly insulted Cocteau, Jean Marais smashed his face, which filled us with satisfaction.”

Cocteau and Natalie Paley, Romanov Princess and Wife of Lucien Lelong

Natalie Paley was the daughter of Grand Duke Paul Romanov, whom Tsar Nicholas II forbade from returning to Russia due to his morganatic marriage. In exile, the Grand Duke asked the King of Bavaria for the title of Count Hohenfelsen – just in time to reconcile with the Tsar and obtain the rank of Prince Paley from him. With this surname, Natalie lived in Paris and the United States, after fleeing the Bolshevik revolution and reaching the Finnish border on foot. Natalie Paley was the only woman with whom Cocteau had both a sentimental and a physical relationship – the latter remains uncertain, Cocteau wrote that he wanted to marry her and make her pregnant.

Natalie had a penchant for homosexual men: before meeting Cocteau, she married Lucien Lelong, the owner of the Lelong fashion house, which would later give rise to Christian Dior. Natalie was part of the creative scene in Paris, setting trends and being photographed by Steichen, Beaton, and Horst. In a drawing, Cocteau depicts Natalie Paley as a sphinx – the body of a lion and a human face – a worthy simulacrum of a possibly traumatic physical experience. Sphinxes are often imagined covered in gold – both as statues and as creatures with fur that shines like metal; it’s common to refer to homosexuals who have never had physical experiences with women as “golden men.” Golden is the title of a song by Mika, another artist with whom I’d like to imagine a conversation with Cocteau, but I’ll refrain.

Cocteau and Cartier: The Relationship with Jeanne Toussaint and the Academician’s Sword

Jeanne Toussaint’s husband went to war with Cocteau’s brother – this created a personal relationship with Cartier’s director. Cocteau often joked and made others laugh when he said that Cartier was the only shop he paid a bill to – Cocteau was wealthy, never had financial issues, and referred to Cartier as a topic of magic. He had the habit of wearing two Trinity rings on his pinky and asked Cartier to craft his sword, the Academician’s sword, in gold and silver, with emeralds, rubies, diamonds, white opal, onyx, and enamel.

Peggy Guggenheim and Marcel Duchamp: A Canvas Held Up in Customs

Peggy Guggenheim and Marcel Duchamp rushed to the customs office in Croydon, England: the officials had detained a sheet on which Cocteau had drawn a portrait of Jean Marais along with two other figures. The drawing, titled Fear Gives Wings to Courage, was done in charcoal and blood: Cocteau had cut himself with a razor to color one of the characters’ bandaged wounds red. Ms. Guggenheim asked why they objected to nudity in art — the guards replied that it wasn’t the nudity or the sexuality, but the pubic hair that required censorship. Ms. Guggenheim promised that she would not display the work publicly but only by private appointment. Cocteau would later visit Guggenheim in Venice, where the famous photo with eccentric sunglasses was taken. There, he collaborated with Egidio Costantini’s Murano glass workshop, which Cocteau would later name Fucina degli Angeli.

Cocteau and Arno Breker, Tristan Tzara’s Pornographic Caricature, Kitsch, and Cinema: The Venice Biennale and the Cannes Film Festival

With Picasso at Café de La Rotonde, the bohemian Montparnasse – let’s go back there. A pornographic caricature of Tristan Tzara, a relationship with the boxer Panama Al Brown. His friends, portrayed naked with their genitals stylized, were the same ones who would later criticize him when Cocteau paid tribute to Nazi sculptor Arno Breker, a favorite of Hitler. On May 23, 1942, Cocteau reviewed Breker’s exhibition at the Orangerie of the Tuileries – an article that would later put him at risk of accusations of collaborationism during the post-war épuration, casting a shadow over him in the following years.

Forays into kitsch with The Eagle with Two Heads, a film telling an imaginary love story between Empress Elisabeth of Austria and an anarchist (in 1898, an anarchist assassinated the Empress in Geneva). In the 1940s, Cocteau made at least four films – moving beyond the experimental phase of the previous decade and culminating in Orpheus (1950): “The collective hypnosis in which shadow and light immerse the audience at the cinema resembles a séance.” Cocteau became a prominent figure in the European film industry, surrounded by a group of talents that formed a kind of circle: Maria Callas, Roberto Rossellini, Marlene Dietrich. From the Venice Film Festival, where he won the critics’ prize, to the Cannes Film Festival, where he chaired the jury in 1953.

Cocteau and Opium: The Clinic Paid for by Chanel, Fernand Léger’s Tubular Cubism

He used opium throughout his life. It started in 1923, when the death of Raymond Radiguet led him to seek his escape from reality. In the 1930s, Coco Chanel paid for his stay at the Saint-Cloud clinic to undergo detoxification. Cocteau published a diary of his rehabilitation, titled Opium, which includes drawings elaborated on poems of pipes and smoking mouthpieces, belonging to a tubular variant of Fernand Léger’s cubism. The bollards on the beach, on the other side of the Saint Tropez peninsula, are re-imagined by his fantasy as mandrakes, the roots used by medieval witches. The drawings in this diary mix organic forms with male body parts: the result is surreal works akin to Salvador Dalí and Joan Miró.

Cocteau Becomes a Brand – Auden and No Artistic Vanity

With Elsa Schiaparelli, he created the eye-shaped earring, featuring a pearl teardrop. He transformed his style into a commercial asset, into a brand: his drawings appeared on the gift boxes of the hairdresser Alexandre de Paris (who styled Elizabeth Taylor’s hair for Cleopatra). His zodiac signs were drawn on matchboxes. It seems Cocteau enjoyed mixing the elite art of galleries and the salons of patrons with the mass market. Soon, many would follow him on this path: Alexander Calder would design for Braniff Airlines planes, and Andy Warhol for Sony Electronics. These forays only enhanced his reputation as a juggler and chameleon. It was the introduction to the cultural fluidity that Lampoon described as a swing between snob and pop, which has now degenerated into populism and consumerism – where the little sex that remains is a sign of honesty and sincerity.

Where has the restraint gone, which once comforted intellectuals whenever they wished to break it? “It is good practice to distrust a famous artist because often famous people begin to play their roles early and become false,” wrote WH Auden about Cocteau, defending him against accusations of being an amateur, and reminding that Cocteau never displayed any artistic vanity.

Carlo Mazzoni