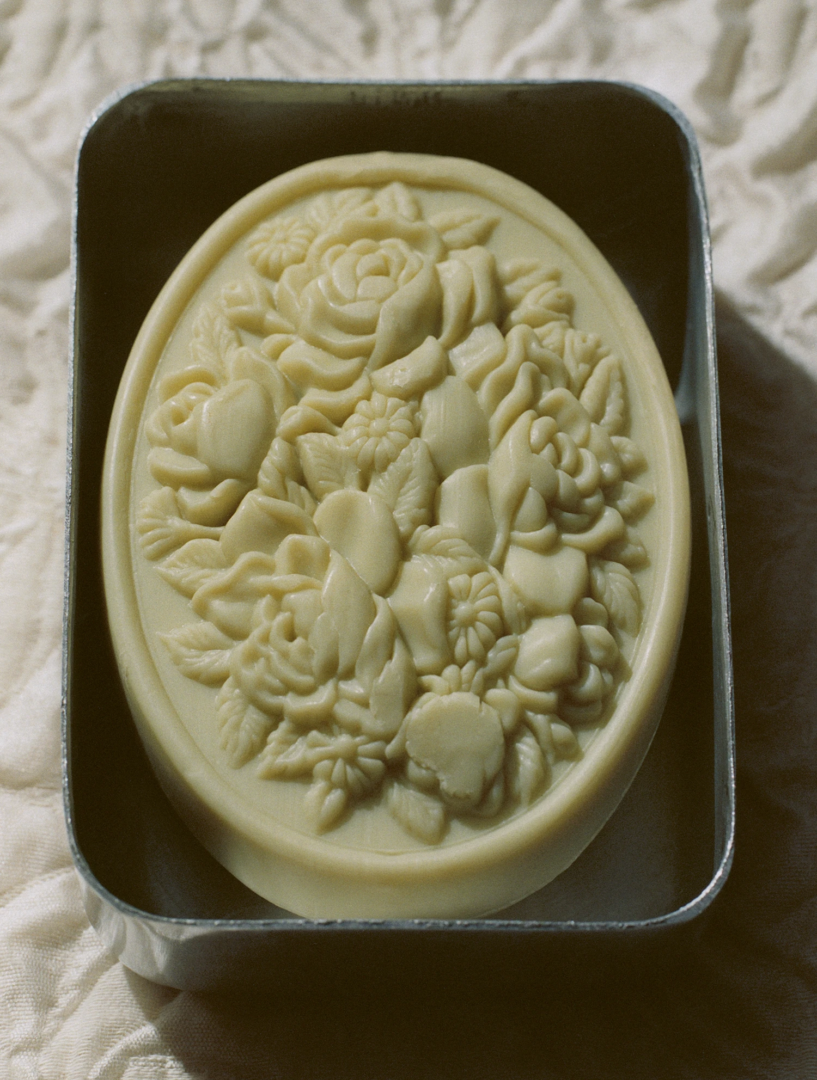

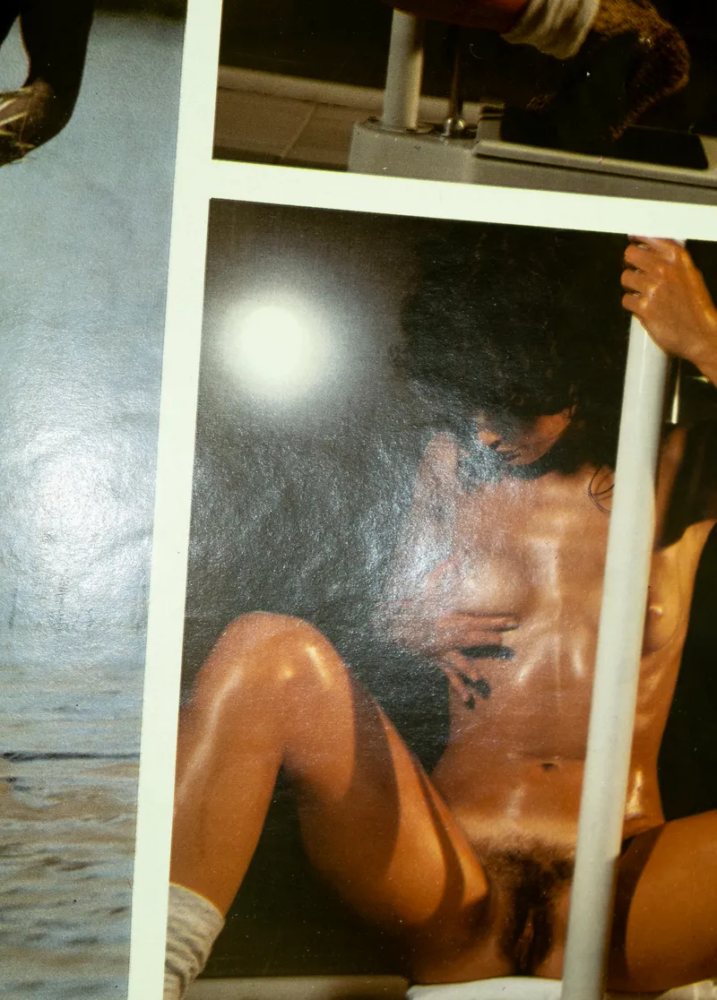

Lampoon SOAP: Lara Giliberto – between Protestantism and Catholicism

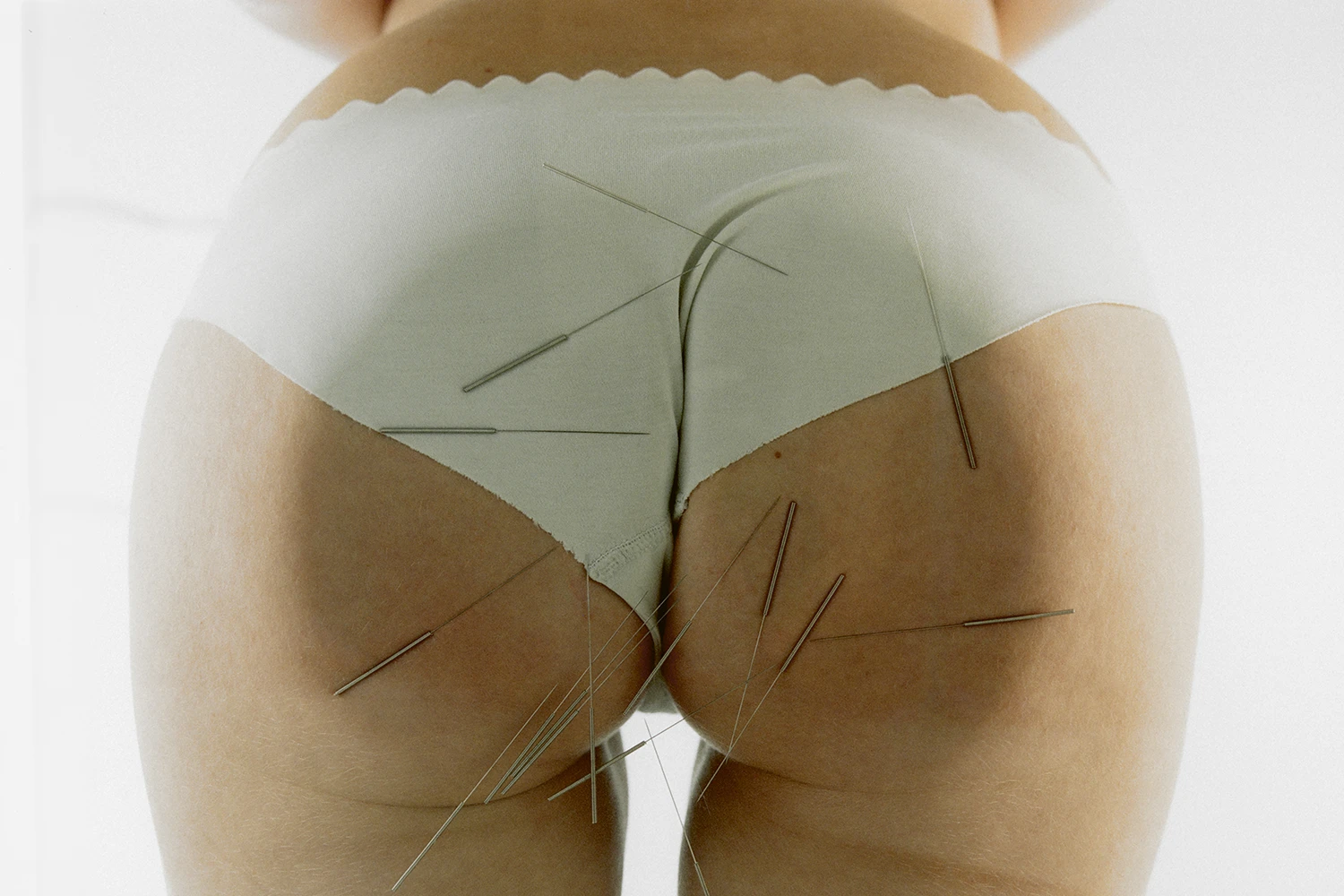

Photographer Lara Giliberto for Lampoon SOAP: tension between redemption and fall – on faith, guilt, and the hidden landscapes of the human soul

Sin Between Protestantism and Catholicism: a tale of two visions of the human soul

The concept of sin lies at the very heart of Christian theology. It defines the relationship between human beings and God, establishes the need for redemption, and gives meaning to the figure of Christ as savior. Yet, despite their shared Christian roots, Protestantism and Catholicism have developed profoundly different understandings of what sin is, how it operates, and how it can be forgiven. These differences, rooted in theological debates from the sixteenth century, continue to shape not only religious belief but also the moral and cultural identities of millions of people around the world.

The Catholic view: sin, confession, and the gradation of fault

In Catholicism, sin is understood as a conscious act that goes against God’s law, damaging one’s relationship with Him and, by extension, with the community of believers. The Church distinguishes between mortal sin and venial sin. Mortal sin is a grave offense committed with full knowledge and deliberate consent—such as murder, adultery, or apostasy—and it completely severs the bond of grace between the individual and God. Venial sin, on the other hand, weakens this bond but does not destroy it; it covers the everyday moral failings that arise from human weakness.

This distinction reveals a Catholic emphasis on moral nuance and human freedom. Sin is not merely a condition of being but a personal act that engages the will. Because of this, Catholic theology insists on the necessity of confession and absolution. The sacrament of Reconciliation allows the believer to confess sins before a priest, who acts in persona Christi—in the person of Christ—and grants forgiveness through divine authority. The act of confession is not only juridical but therapeutic: it heals the soul, reestablishes communion with the Church, and invites the sinner to conversion.

The Catholic understanding of sin, therefore, is embedded in a sacramental and communal framework. Sin affects not only the individual’s private conscience but the mystical body of Christ itself. Redemption, likewise, occurs through the mediation of the Church and its sacraments.

The Protestant Reformation: sin as condition and faith as response

When Martin Luther and other reformers challenged the Catholic Church in the sixteenth century, their protest was not simply institutional but profoundly theological. At the center of their critique was the idea of sin and human incapacity to overcome it through works or sacraments. For Luther, sin was not just a series of moral failures; it was a radical condition of human nature after the Fall. Humanity, in his view, is bound by sin and cannot, by its own effort, return to God. No ritual, pilgrimage, or indulgence can erase the corruption of the human heart.

From this perspective, salvation is not earned but received through faith alone (sola fide). Sin is forgiven not because of human merit or priestly mediation but through the believer’s trust in God’s grace, made manifest in Christ’s sacrifice on the cross. The confessional booth is replaced by an intimate dialogue with God in prayer. The believer stands directly before God—sinful yet justified by faith.

Protestantism therefore places the drama of sin and redemption entirely within the realm of the individual conscience. The community of believers remains important, but it does not mediate divine grace. Each person is responsible for their own faith, for their own reading of Scripture, and for their personal relationship with God. This spiritual autonomy marks one of the deepest divergences between Protestant and Catholic thought.

Moral consequences: guilt, grace, and responsibility

The differing theologies of sin have profound consequences for how believers understand moral life. In Catholicism, the moral universe is graded and structured. The faithful can rely on the Church’s moral teaching and on confession as a recurring moment of purification. Sin and forgiveness are part of a dynamic journey of conversion supported by the community.

In Protestantism, morality takes on a more existential tone. Since sin is an inevitable condition, believers are constantly reminded of their dependence on divine grace. This has often produced an acute sense of guilt and self-examination, visible in the spiritual diaries and sermons of early Protestant writers. Yet it has also generated a strong ethic of personal responsibility and sincerity before God. Good works are not the cause of salvation but its fruit: evidence that faith is alive and active.

Two visions of human nature

Ultimately, the difference between Catholic and Protestant ideas of sin reflects two distinct anthropologies—two ways of understanding what it means to be human. Catholicism views humanity as wounded but capable of cooperation with grace. The human will, though fragile, can participate in its own redemption. Protestantism, by contrast, emphasizes the radical incapacity of the human will and the absolute sovereignty of grace. For Luther, even faith itself is a gift from God, not a human decision.

Despite these contrasts, both traditions share a deep awareness of sin’s seriousness and of humanity’s need for reconciliation. They agree that sin separates humanity from God, but they disagree on how that separation can be healed: through sacramental mediation or through faith alone.

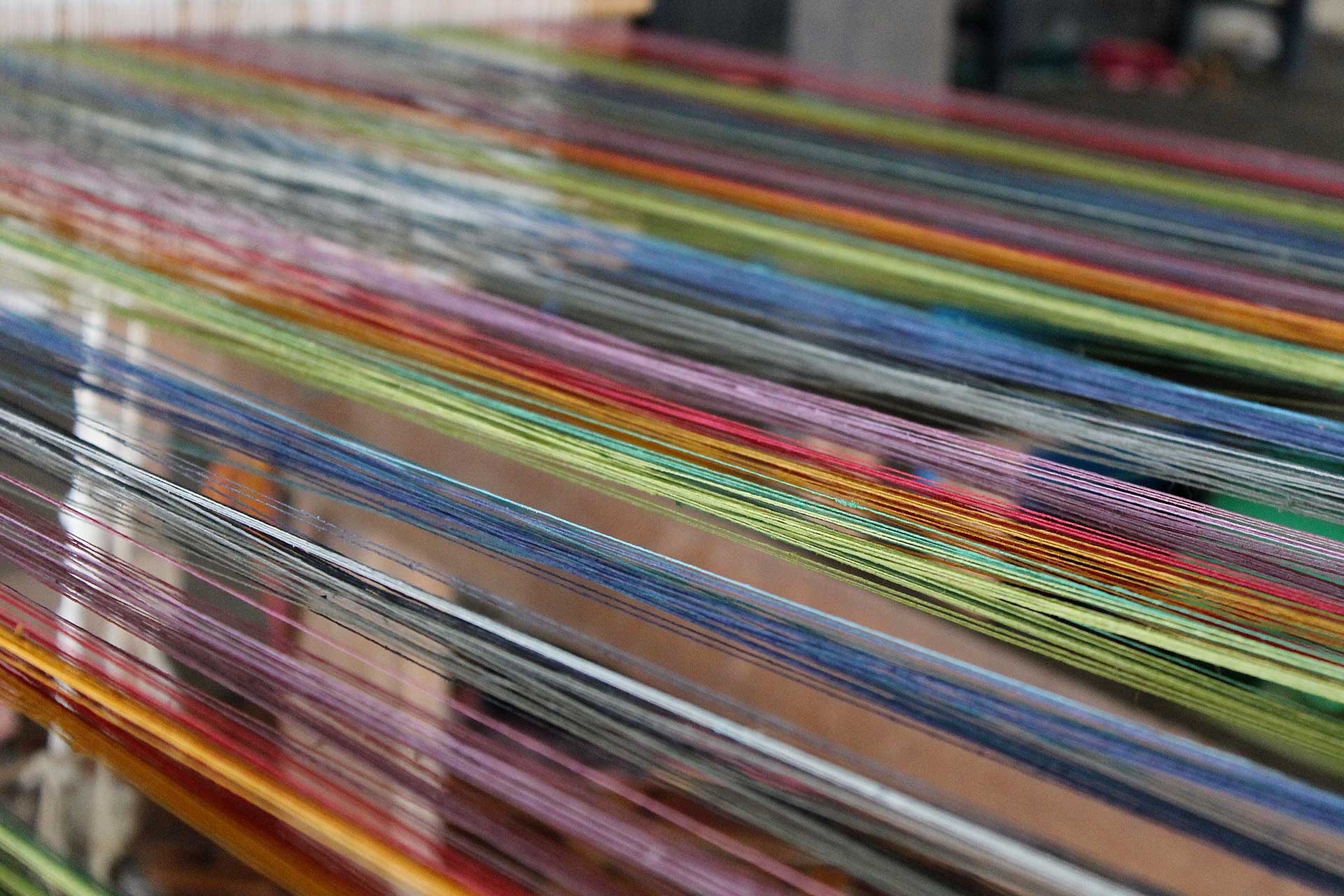

Lara Giliberto, photographer – fashion, beauty & still life

Lara Giliberto is an Italian-born, Paris-based photographer specializing in fashion, beauty, and still life photography. Her work blends a refined sense of composition with a distinctive use of light, capturing subtle emotions and textures through a minimal yet evocative aesthetic. Over the past decade, Lara has collaborated with leading international magazines and fashion houses, creating editorials, advertising campaigns, and visual concepts that merge elegance with contemporary vision.

Her photography is characterized by a poetic approach to detail and materiality — where simplicity becomes a language of its own. Each image reveals a quiet strength, shaped by natural light and emotional precision. Lara’s creative universe extends beyond commercial projects, exploring personal narratives and experimental still life series that reflect her sensitivity toward color, form, and atmosphere. Based in Paris, she works internationally across editorial, fashion, and beauty industries.