Les Lalanne — originality in an era of covers and revivals

For François and Claude Lalanne, a hippopotamus could become a bathtub. Whether in an exhibition or at an auction, this is how collectors’ obsessions begin

Les Lalanne’s surreal metamorphoses: from hybrid creatures to functional sculptures

About a decade ago, Les Lalanne were slightly out of fashion. Then, at TEFAF Maastricht, dealer Ben Brown decided to present their animal-furniture, Ovid-like metamorphoses cast into metal alloys. This was perhaps the spark that ignited the fascination of a new generation of collectors for François-Xavier and Claude Lalanne, partners in both life and work.

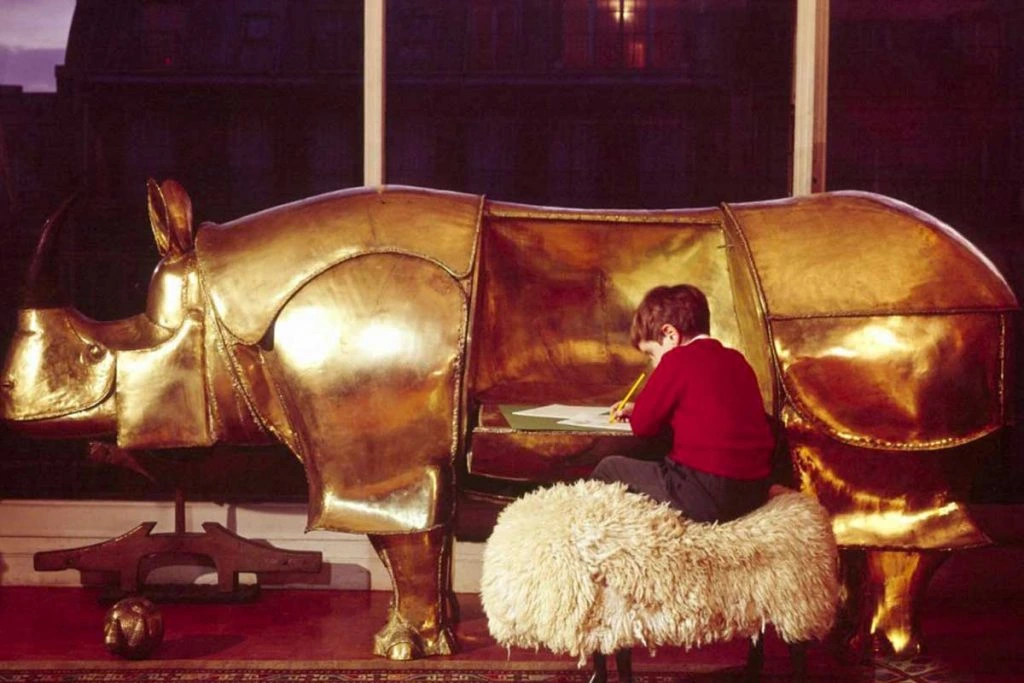

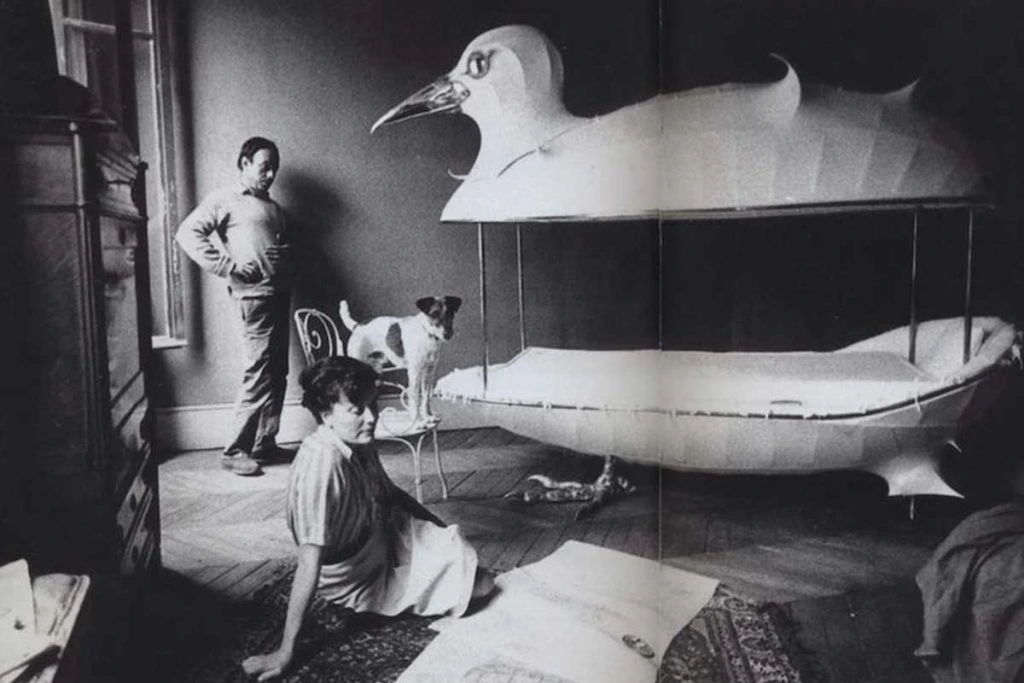

The duo invented without limits: the choupatte, a horse with chicken’s feet; the Rhinocrétaire, a rhinoceros turned into a brass writing desk; a camel sofa; and a hippopotamus that became a bathtub. The Gorille de Sûreté concealed a safe, while a seagull with a gilded beak contained a cocoon-like bed fit for a Grimm fairy tale.

Brown staged these sculpture-furnishings alongside Alighiero Boetti’s word games and Josef Albers’ chromatic abstractions, creating an alienating and unforgettable dialogue.

From Yves Saint-Laurent to Jacques Grange: how Les Lalanne conquered collectors and auctions

Some admirers supported Les Lalanne from the very beginning, such as legendary Parisian interior designer Jacques Grange. Their creations earned iconic status at the 2009 auction of Yves Saint-Laurent’s Parisian home, when bidding soared. Claude herself admitted she was astonished to have become an icon, often adding with amusement that she was simply happy objects made for close friends like Saint-Laurent and Pierre Bergé had found such recognition.

Momentum was reinforced by Peter Marino’s 2010 retrospective at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. Three key gallerists also played a decisive role: Ben Brown in London and Hong Kong, Paul Kasmin in New York, and Jean-Gabriel Mitterrand in Paris since the 1980s.

Les Lalanne in the 1960s art scene: from Agnelli’s sheep to Günther Sachs’ patronage

We live in an era dominated by covers and revivals—often blatant, sometimes disguised as novelty, as if memory and tomorrow did not exist. In the 1960s, however, Les Lalanne were already a phenomenon. They seduced collectors such as the Rothschilds and the Agnelli family. Gianni Agnelli alone ordered at least twenty of their moutons, white sheep with burnished bronze feet and faces, famously photographed in his Milan apartment designed by Gae Aulenti.

Their patrons included Marie-Laure de Noailles, an indefatigable patroness, and playboy Günther Sachs, Brigitte Bardot’s husband from 1966 to 1969, who was among their very first supporters. Married since 1967, François-Xavier and Claude positioned themselves outside the critical debates of their time, cultivating instead an imaginative and nature-driven aesthetic.

Recent Sotheby’s previews confirm their continuing allure. A diminutive gilded metal chair by Claude, woven with bamboo branches and leaves and reminiscent of Perrault’s fairy tales, drew immediate attention in Monte Carlo, just as Gabriella Crespi has recently experienced a revival of her own.

Dior and Maria Grazia Chiuri: Claude Lalanne’s jewelry between myth, metamorphosis and nature

Maria Grazia Chiuri remembers Claude Lalanne with admiration. For her first Haute Couture collection at Dior in January 2017, staged at the Musée Rodin, she asked Claude to design jewelry: necklaces in the form of butterflies, flowers, and mistletoe, alongside belts shaped as snakes and brambles.

“I visited her several times at home in Paris and in her atelier near Fontainebleau,” says Chiuri. “She was hypnotic to watch, her hands bending, shaping, engraving metal as if it were paper. Such strength and precision at more than ninety years old. She worked with her grandchildren, casting by lost wax, creating pure magic.”

Claude often drew inspiration directly from nature. She would immerse plants and vegetables into electroplating baths, transforming them into golden or silver objects—a modern philosopher’s stone inherited from her father’s fascination.

Yves Saint-Laurent’s interiors and fashion experiments with Les Lalanne’s surreal designs

For Dior, the Lalannes also designed the décor of the Avenue Montaigne boutique when Yves Saint-Laurent was still a young director. Later, in 1965, they created an egg-shaped bar for Saint-Laurent’s private residences.

At Rue de Babylone in Paris, they conceived an atmospheric music room: candle-lit mirrors framed by copper vines and bronze lianas, a nocturnal retreat with Proustian undertones. In Tangier’s Villa Mabrouka, a mirror framed by vegetation hung above a marble fireplace, another example of their blending of nature and interior architecture.

Their work with YSL also extended to fashion. In 1969, Claude molded a gilded breastplate directly from model Veruschka’s torso, paired with flowing chiffon gowns in black, brown, and Klein blue. These Amazon-like bodices caused a sensation on the runway, clashing with the spirit of May ’68.

Between Pop Art and sacred references: François-Xavier and Claude’s symbolic bestiary

Les Lalanne’s work oscillated between the surreal and the mythic. Claude’s jewelry for YSL was in galvanized copper, poetic yet provocative. At the Whitechapel Gallery in 1976, they exhibited sardine tins—Pop art infused with Eastern lyricism.

François-Xavier found inspiration in Egyptian antiquity, Pompon’s bestiary, and Brancusi, with whom he shared late-night drinks in Montmartre. His oeuvre included thrones topped with ginkgo leaves, chairs with crocodile skins, Singe Douche and Lapin Polymorphe, and minotaurs and centaurs cast in bronze. Their Histoires Naturelles series blended bronze with glass paste: ostriches holding console tables, fairy-tale cutlery, plant-blooming furniture, and jewelry bristling with thorns.

From Claude Dupeux to Les Lalanne: two distinct processes united under one name

Claude Dupeux was born in 1925 and trained at the École des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. From the beginning, she combined functionality with sculpture. After a first marriage to architect Jean Kling, she met François-Xavier in 1952. He loved animals, she loved plants: the synthesis became Les Lalanne.

They worked independently but under the same signature. Claude handled molding and assembly, François-Xavier focused on design and construction. Their styles were complementary yet distinct: Claude’s structural classicism and François-Xavier’s baroque imagination.

Starting with objects for department stores and theatre sets, they soon became established artists, supported by figures like Jean Tinguely, Niki de Saint Phalle, and dealer Alexandre Iolas. Claude’s Arcimboldo-inspired clock, praised by Salvador Dalí and Gala, opened doors to the surrealist circle.

Friends, collaborations and lasting legacy: Dalí, Gainsbourg, Lagerfeld and beyond

In 1968, Claude’s Homme à la Tête de Chou inspired Serge Gainsbourg’s album of the same name. Friends included Karl Lagerfeld, Marcel Duchamp, and Teeny Duchamp. Peter Marino later commissioned furniture for private interiors and Dior stores. Chanel also benefited from their talent.

Claude had her only solo exhibition in May 2018, organized by Jean-Gabriel Mitterrand, followed by one dedicated to François-Xavier. Upon her passing, Mitterrand described her as “a fortress against bad taste and pretension. She used humor to dispel mediocrity, never bending to avant-garde dogma or fleeting trends.”

Les Lalanne’s originality lay in this refusal to conform: their art, halfway between sculpture and design, continues to embody imagination, metamorphosis, and the timeless poetry of nature.

Cesare Cunaccia