Linder Sterling: the ultimate recycler of pornographic imagery

An interview with artist Linder Sterling – armed with a surgeon’s scalpel, she cuts away at imagery from magazines to create visual narratives exploring the body and mind of feminism

Interview with Linder Sterling: Radical feminist narratives and gender as visual performance

A female form with an iron box for a head and lips for nipples — this is the record sleeve of Orgasm Addict by British punk-rock band The Buzzcocks. British artist Linder Sterling’s aesthetic signature inspires a conversation on what it means to be a woman. She explores sexuality, gender construction, and desire through the female lens.

Her cut-and-paste photomontages — built predominantly from images found in pornography magazines — have been making their mark on counterculture for decades. Now just shy of seven decades herself, Linder has mastered the pen, brush, and scalpel as her tools and explored the stage through confrontational performance art and her punk band Ludus.

Through the years, Linder’s visual narrative of the body has evolved — from questions of sexualization and gender roles to deeper reflections on women’s rights and health. Her photomontages are formed by cutting images from magazines with surgical precision and engineering them to create a visual language of resistance. She also speaks openly about the importance of not editing one’s life.

Feminism, punk art, and cutting to the core of female experience

Aarushi Saxena: Let’s talk about your narrative: it is often worded as radical feminism through punk art. How would you put it?

Linder Sterling: “Radical feminism through punk art” has almost become the journalistic mantra for talking about my work. Punk and feminism are bedfellows. Discovering second-wave feminism as a sixteen-year-old in England rewired my brain and made me think in a different way. Feminism changes, evolves, and responds — therefore, it should always be part of the definition. Punk, on the other hand, only occupied a few years of my life. Sometimes things need to be pared down. In my work I use a scalpel to cut images to the bare minimum; in a similar way, my current title is simplistic.

Bodies, commodification, and the performance of gender identity

AS: Human anatomy is your prime subject — from earlier depictions of sexualized women to now exploring gender dynamics. How do you perceive the body and its commoditization?

LS: In my late sixties, having lived through almost seven decades, I’ve watched the commodification of the human body go off the scale. I often return to Simone de Beauvoir, who said, ‘One is not born a woman but becomes one’ — she nailed those cultural expectations early on. Gender, to me, is similar to performance art. We are in a period of flux. We are examining gender in a volatile way, and I observe the debate around it closely. I have friends of all ages who had a callous time growing up, feeling that they couldn’t perform the role of a boy, girl, man, or woman with any confidence, and then suffered all sorts of mental and emotional challenges. This generation is challenging all those previously fixed notions of gender.

Linder Sterling: Childhood trauma, pornography, and subversive reappropriation

AS: Pornography in your work: why and how did this influence manifest?

Linder Sterling: As a young child, pre-literate, someone in my family circle would show me pornographic images. Now we call this ‘grooming’. Thankfully, my parents intervened when they discovered it, but for quite a long time, I was being groomed for what I presume was a horrific level of future intimacy. Between those images of bunny rabbits and fairy tales like Cinderella, there was an abuttal of pornography. This aspect of my childhood is something I’ve returned to in my work many times. In an upcoming exhibition for Blum & Poe, there’s an introduction to the incest motif via Myrrha — a mythological character from Greek mythology.

In my early years, I was trying to find out what kind of woman I was supposed to be through the lens of both pornography and fashion. These were the two worlds where women were most frequently represented. I didn’t have access to explicit pornography until 1976. Instead, I bought women’s and men’s magazines — fashion, gardening, cars, DIY — hoping to find some kind of reflection, some image with which I could find parity. I didn’t find it in pornography, because it’s always photographed through a predominantly male lens. But a fascination stuck with me, because this imagery can be derailed — and it’s the perfect material to subvert using photomontage.

From drawing to scalpel: how photomontage became a feminist tool

AS: Why montages? Is there a reason behind the deconstructive approach?

LS: Growing up in the 1950s, there were only two channels on television and nothing to do at home. I drew every night and was highly skilled by the time I was eighteen. I went to art school and continued to draw, but eventually I got bored and frustrated with mark-making. One day in 1976, I cleared away everything that would leave a trace, and all that remained was a scalpel I had been using to cut mount boards. I started cutting up magazines. It was liberating. Joyful.

Because I used a No. 11 blade — a surgeon’s scalpel, manufactured for making stab incisions in the operating theatre — I began making stab incisions into magazines, treating the magazine itself as a body. It felt like I was dissecting both the publication and the imagery within it, with the cool precision of a surgeon.

I could’ve drawn for a whole week and never produced an image as shocking as a photomontage that took me ten minutes to create. My early photomontages from 1976 aren’t complex compared to later works. One of the most known is the Orgasm Addict cover for the Buzzcocks. Even now, if I can get a single motif that makes the host photograph resonate in a new way, I don’t overwork it. I’m a concise engineer of the found image.

Linder Sterling, the interview – punk, democracy, and vocal expression as visual art

AS: You founded the post-punk band Ludus — what was the relationship between your music and your photomontages?

LS: In late 1976, pop culture was accelerating and became known as punk — although ‘punk’ was an American name. We all hated it in the UK because it didn’t represent what we were doing. Still, punk created an instant democracy on stage. Anyone could pick up a guitar or drumstick or sing. For a while, it seemed unnatural not to be on the stage.

By that point, I had also been drawing for over twenty years, and I became interested in using the larynx the same way I had used the pencil or the scalpel — using the word to make my mark.

Violence, autobiography, and why Linder Sterling rejected photography

AS: Using found images versus original photography. What is your preference?

LS: I believe autobiographies should not be edited — particularly not to remove unforeseen acts of violence. Violence, like love, shapes one’s future in radical ways. One reason I started using found images dates back to 1976, when I was on my way home after photographing The Damned at The Electric Circus in Manchester. I was attacked by a rapist — unsuccessfully. He stole my camera. That incident stopped me from taking photographs again. Cameras became cursed. I associated them with trauma.

I also avoid digital photography. It’s too clean, too antiseptic. I like working with print media from the last century — it’s sensual. I use my nose a lot. I can smell the decade of a magazine. I can identify if the paper is from the 1940s or 1950s. A single fragment is enough for my sensory detective work. Digital has no smell. It doesn’t offer the same resistance. There’s no glue, no tactile friction. You can’t grasp the materiality of pictures the same way.

Archiving pornography: a social repository of forgotten images

AS: What magazines do you frequent to create your montages?

LS: Lately, people have started donating pornography belonging to deceased relatives, friends, or husbands. I feel like a social repository. People know I’m the ultimate recycler of this imagery. No magazine ever goes to waste. I have print media from the early 20th century to the present day.

Satire, gags, and the political roots of photomontage

AS: There’s a tilt of satire and humor in your work. Can we speak about the intention behind that?

LS: A joke is called a gag — but gag also means something that mutes you, censors you. I’m aware of that double meaning. Humor can puncture the enemy’s rhetoric in dire situations. Photomontage, as a technique, emerged after WWI — rooted in opposition and shock. It always returns during civil unrest, wars, or cultural debates.

Humor is invaluable. It’s part of the history of DADA and Surrealism. Artists like John Heartfield created monstrous oppositional images of Hitler. I’m seeing similar extreme imagery from the war in Ukraine. I was born in Liverpool, and there’s a unique wit in that city. Nobody takes themselves too seriously. That Scouse humor lives in my work.

Censorship, publishing obstacles, and feminist rebellion in the 1970s

AS: Let’s talk about censorship and rebellion when producing your art.

LS: Censorship can be pernicious depending on who’s enforcing it — it can take root like a virus in some minds. At the same time, it’s necessary to protect the vulnerable. An eight-year-old can now see more explicit sexual imagery via a phone than I ever could at eighteen.

My generation never thought about galleries. The art world was dull. We had to self-publish — fanzines, record covers, t-shirts. When I made my first photomontages in 1976, I used my name, Linder. Everyone assumed I was a man. Only a man would dare to buy and cut up pornography. Reproducing my work was hard. Manchester had just one photocopier. The woman running it refused to print my work. She said it was pornographic.

Image as battlefield: visual action-reaction and symbolic power

AS: Does the concept of action-reaction have a meaning to you, and do you try to translate this into your work?

LS: Every photomontage I make transmits action-reaction on a visual level. I use cut-outs from diverse sources, and each fragment competes for the viewer’s attention. A picture of BREXXITT might push back against images of snakes, blossoms, or eagles. The optic nerve has to work hard.

Symbolism depends on cultural context. A snake in Texas might mean one thing; in Bombay or Belgium, something else entirely. Gertrude Stein said, “A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose,” but I’m not sure that’s true.

Lampoon collaboration: Linder Sterling, serpentine energy and inner transformation

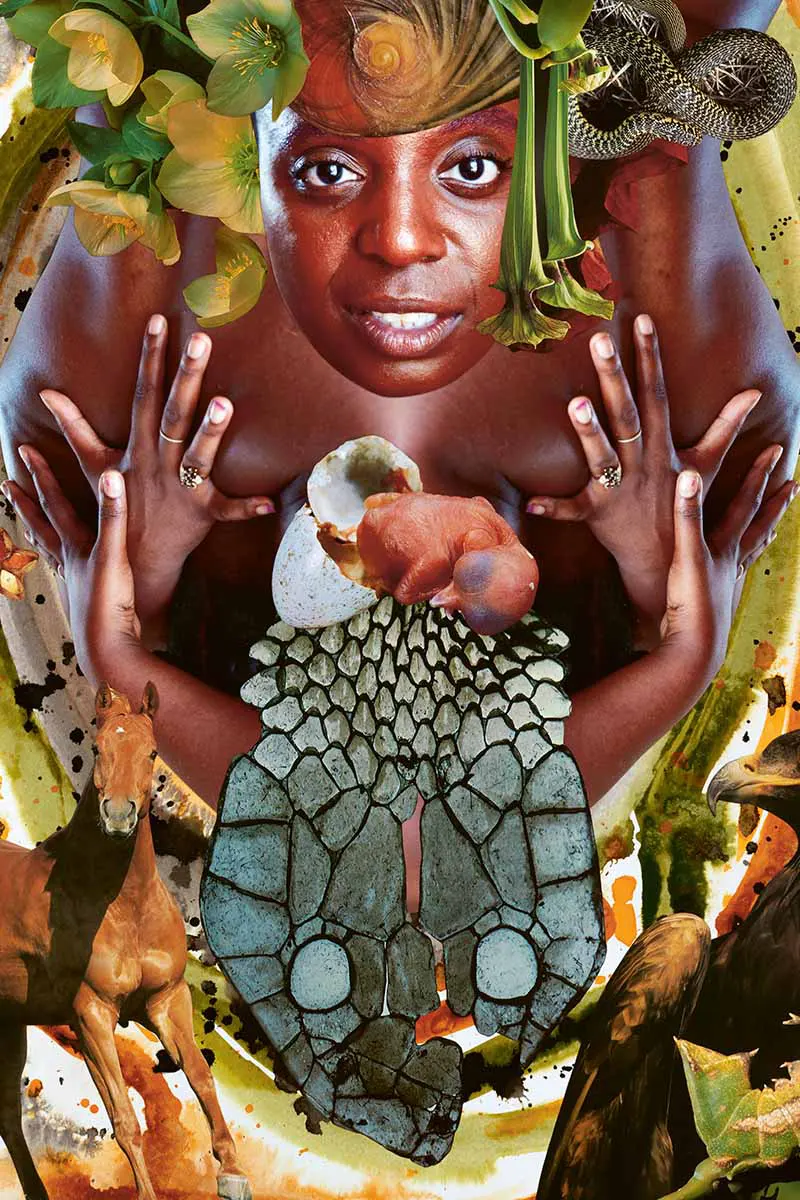

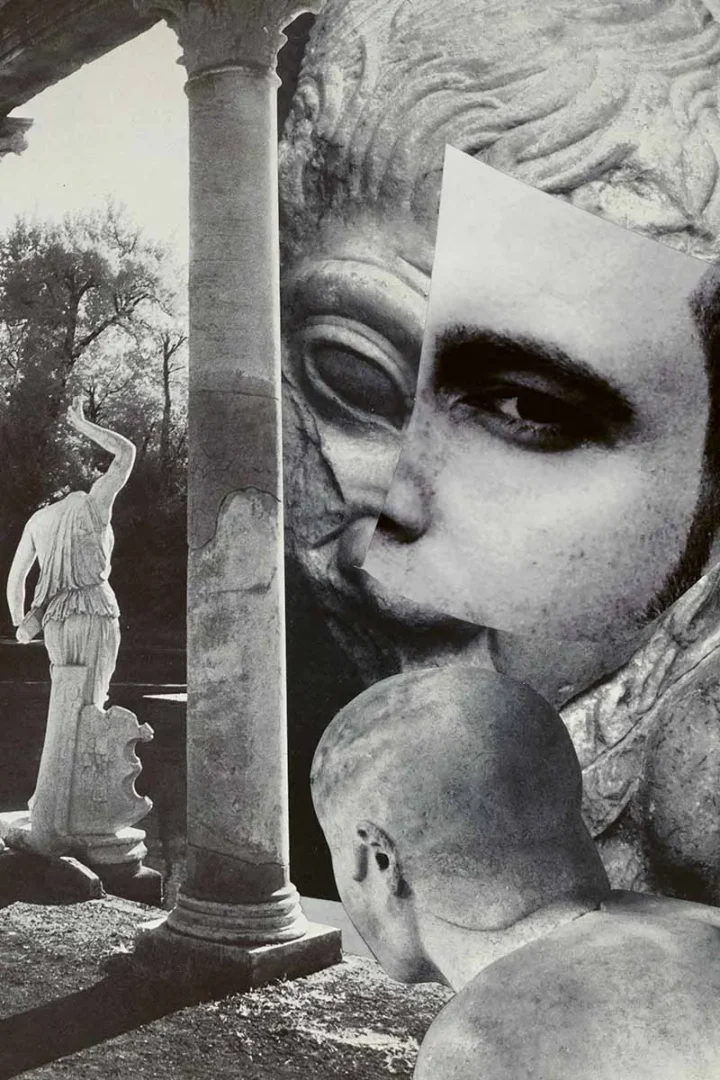

AS: Your recent montages for Lampoon — what is the story, who are the artists?

Linder Sterling: The main montages feature BREXXITT from the Texas-based House of Kenzo. I was introduced to BREXXITT by the musician and producer Rabit (Eric Burton). We’ve been in close dialogue for nearly a year, developing montages in response to his new album What Dreams May Come. He said, “This feels like a discovery process… not extractive.”

While working on Lampoon, I thought about interior worlds, twinning, kundalini energy, transformation, and reflection. I also considered Roman mythology’s deep influence on American culture, and the cycles of nature versus nurture. All works were made by hand — scissors and glue — not digitally. It’s a tradition rooted in the earliest days of photography.