Martino Gamper: Rough, Rocks and Corners

I prefer removing material over adding. Martino Gamper’s design process transforms raw materials into narratives – embracing limits as creative tools, he combines cutting, refining, and collaboration to reveal hidden facets in every piece

Cutting Rocks with Martino Gamper

I begin by analysing where the rock is located, its geography, understanding its type and age, and how it ended up there. I ask myself whether I want to move it or leave it where it is. These are rough, untouched rocks, not yet shaped into building materials. They exist purely by chance, full of potential: to be broken down, refined, and imbued with stories. They are coarse and raw.

I create a conceptual framework around the rock. Stories and narratives are essential to transforming and moving them. Typically, I work with an overarching concept that gives me freedom. For example, if I had to create a unique story for each individual chair, the process would be overwhelming. Having a clear direction – such as making the 100 chairs project – it helps me getting lost. Setting limitations, like making a chair a day, paradoxically frees me. It defines my path and allows me to be creative within those boundaries. The same approach applies when dealing with roughness; I set a goal or a roadmap, and once that’s defined, I’m free to explore.

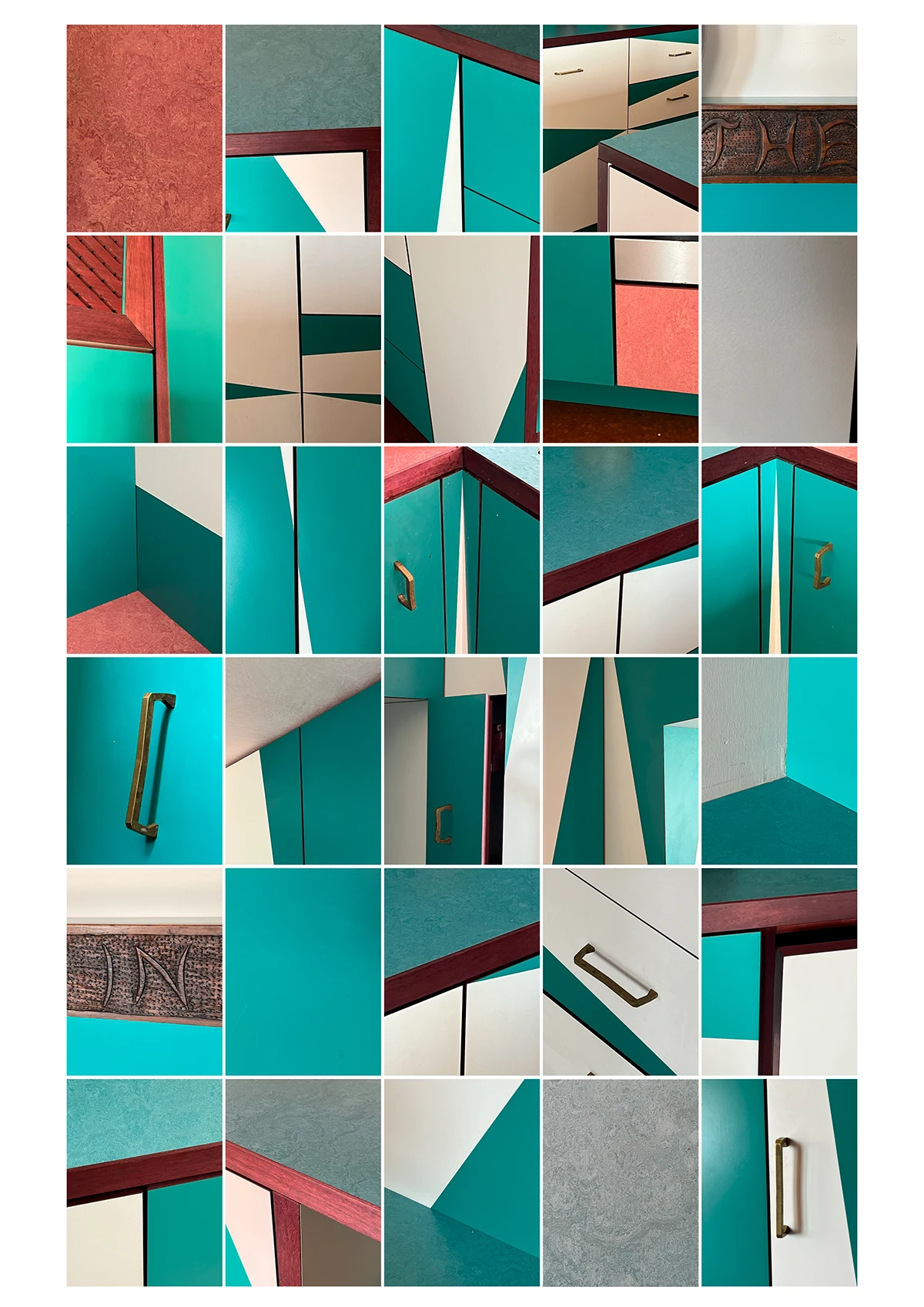

When you cut a rock, you may split it into two pieces, creating new objects. Or you might remove what’s unnecessary, opening up new possibilities. I naturally imagine cutting away corners or bits – cutting becomes a useful tool. I prefer removing material over adding. This process can also lead to collages, as cutting different objects often leads to joining them in unexpected ways.

Once you cut, you reveal an artificial surface in contrast to the rough, natural one. This act of cutting exposes new possibilities, revealing something hidden within the rock. Cutting is about discovery. After cutting comes polishing, a later stage in the process. By revealing a new surface, you might then want to smooth and refine it. It’s a theoretical position too: reducing complexity and isolating key parts.

Martino Gamper: Prototype is the finished object

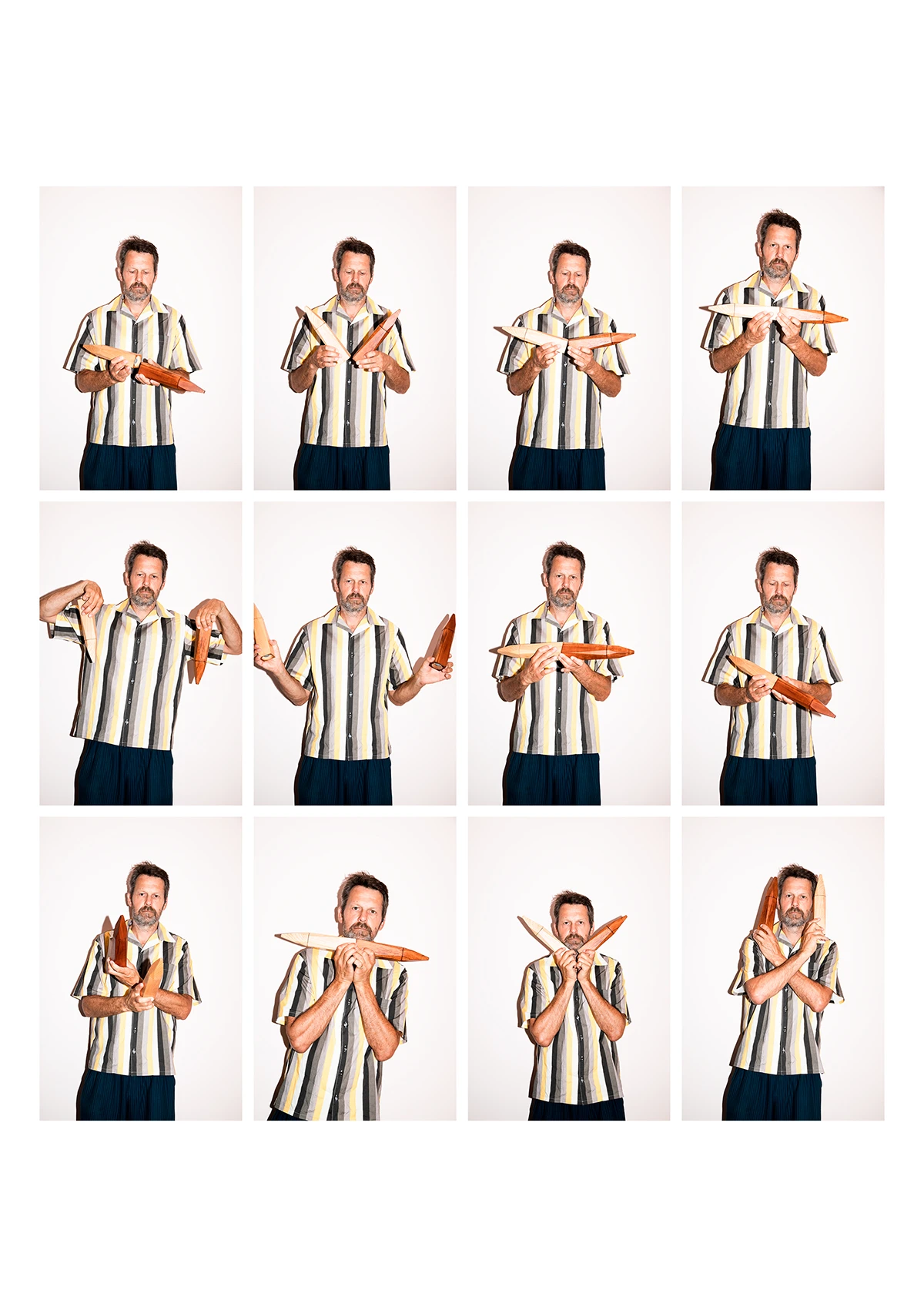

Once I start thinking about a project, I can’t stop. The 100 Chairs in 100 Days project was a form of research, a way to explore the concept of the chair and what it means to design one. Similarly, with the Hookaloti hook project, I wanted to experiment with different materials, processes, and tools. Once I immerse myself in a project, it can become obsessive. As designers, we’re always reinventing the wheel, but I prefer diving deeply into a project and then stepping back, rather than lingering on it for too long.

Sometimes the prototype becomes the finished object, or at least I treat them both equally. Prototypes are part of the thought process and the work in progress – they’re all part of the same conversation. Often, I create objects that remain one-offs, existing in that initial state. However, I might return to refine them later.

First, there’s a rough sketch. After solving its problems, I might revisit it and refine it even further. In my practice, prototypes are often as valuable as finished pieces.

The prototype is usually the first thing I create, and it comes quickly, without being overly precious about it – and there’s something freeing in that. The first attempt is about making the object work, while the second round is more about refining it, maybe even polishing it as a form of decoration. It’s a process, a journey with four key stages.

The first is location: geographically, where am I working? This could be a country, a smaller region, or even a specific city. The second stage is space – considering the architecture or spatial context: is the project indoors or outdoors? What is the history of the space? Then, there’s the people involved—who is using or interacting with the project? From these considerations, I derive what I call “behavior”: how does my intervention influence interactions, and how do tools and materials play into that?

These stages don’t follow a strict order. I might begin at the behavior stage, as I did with the Sitzung project at Haus der Kunst in Munich, which centered on sitting and meeting. The project unfolded from there to consider people, location, and architecture. I navigate between these four elements, each one informing the final result.

Piggybacking according to Martino Gamper

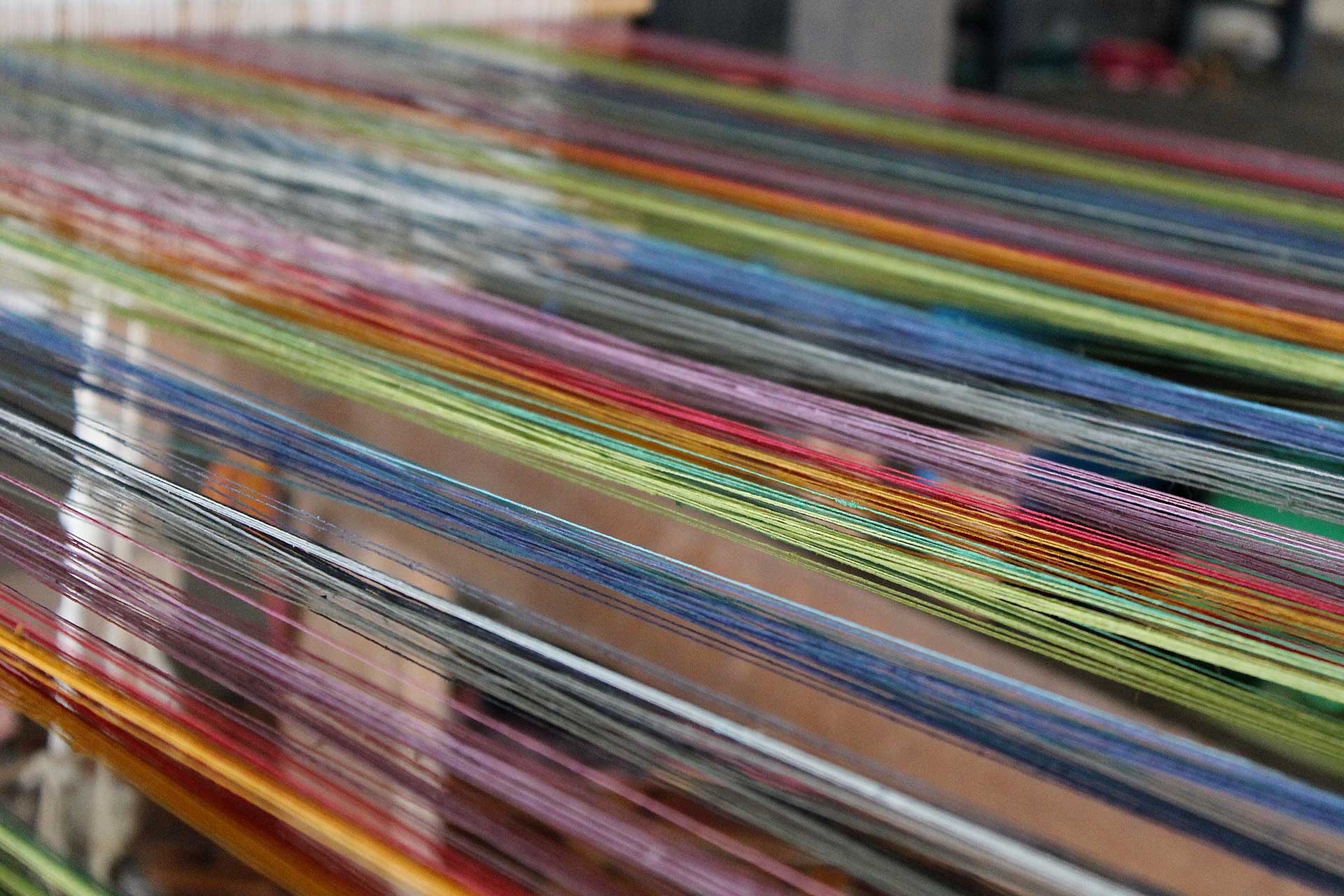

I like the image of piggybacking: collaboration is something I enjoy because it’s more fun working with others than doing everything alone. Whether we’re creating for ourselves or others, we are always dealing with people, and conversations become moments of learning. Starting with a rough idea, we define and refine it together, gaining clarity and resolution through collaboration.

Collaboration, like roughness, can be stimulating. There’s a sense of vibration when energy flows smoothly, creating synergy and trust. When trust is lacking, things feel sharp and edgy – not just rough, but abrasive. However, when I can share something with someone, even if it’s still rough, at least it doesn’t hurt anyone.

The process often starts when I’m looking for or stumble upon furniture. Objects begin as rough sketches, rough ideas, but after spending time with them, I understand how they can come together. Each object has a personality, shaped by its maker, and I create narratives, assigning roles to each piece. Cutting and shaping objects helps me develop a storyline.

Roughness also comes from not knowing enough. When I find a chair or piece of furniture that I like visually but don’t know much about, I research it. Roughness, in this sense, is the condition before you discover the story or history behind an object.

Continue reading on Lampoon #30 The Raw Issue

Carlo Mazzeri