Maurizio Cattelan: Art is not a detergent. It doesn’t clean, it stains

An interview with Maurizio Cattelan: art shouldn’t wash anything away. I don’t want people leaving reassured or clutching a moral. If something sticks, let it be friction

Maurizio Cattelan proves art isn’t a detergent as rough surfaces and Comedian’s rotting banana boldly critique production waste

Maurizio Cattelan: Art isn’t a detergent: it doesn’t clean, it stains. Every piece I make is a surface that looks polished but hides scratches, fingerprints, residue. Rough is anything that resists the glide of the hand and the eye. If buffing something is a form of control, I prefer the raw edge—the in-between zone where you’re not sure whether the thing is still dirty or finally true.

The banana rots, but the gesture stays. It’s the opposite of waste: an investment in paradox. Comedian isn’t a hymn to throw-away culture; it’s a mental trap, a product that self-destructs and multiplies at once. If something so perishable can outlive many “permanent” masterpieces, maybe the system is rotten, not the fruit. When art works, it makes you look at a dumpster and think of a museum—and vice versa.

America’s solid-gold toilet by Maurizio Cattelan: luxury into a grime-filled paradox, greenwashing

MM: America, the solid-gold toilet at the Guggenheim, needs constant scrubbing; it becomes a little ecosystem whose survival depends on maintenance.

Maurizio Cattelan: America may be the work that, while demanding all the care of a traditional piece, also has to be scrubbed with limescale remover. It’s precious, yet subject to the same human grime as a highway restroom. Outwardly it’s an icon; practically it’s a sink clogged with meanings. High and low, sacred and sanitary meet there. Part of its value is precisely this: you have to get your hands dirty to keep it immaculate.

MM: You routinely opt for marble, gold, and resin—materials many colleagues avoid today in favor of low-tech or recycled stuff. Your choices often read as a commentary on cultural greenwashing and, at the same time, a deliberate courting of paradox.

Maurizio Cattelan: I never pick a material to be the good or the bad guy. I choose what the idea needs, even if it looks out of fashion. Marble is no longer eternal; gold no longer shines the same. Some materials feel almost embarrassing now, and that’s why I like them. Nothing is truly clean, not even recycled matter—it depends on how you use it, on the story you tell. If there’s a paradox, it’s that luxury can be the best way to talk about failure.

Permanent Food, Maurizio Cattelan’s cannibal magazine, foreshadows algorithmic image scraping and normalizes remix culture amid fears of visual plagiarism

MM: Permanent Food, the magazine you made with Paola Manfrin, literally devoured other magazines—an act that now feels like an analogue preview of algorithmic image-scraping.

Maurizio Cattelan: Permanent Food began from a simple wish: our own magazine, no budget, no rules. We adored glossy mags, those visual monsters that pull you in for reasons you can’t name, so we made one that swallowed them all. We bought every title in the newsstand, tore out the pages that felt strongest, most ambiguous, most irresistible, and reassembled them into a new object—no credits, no explanations, straight to the printer. Looking back, it foreshadowed how images now circulate—looted, re-stitched, source-less. We just did it by hand, starving for it.

MM: Years later, in our remix culture, it feels as if Permanent Food blurred the authorial line ahead of its time. Visual plagiarism now looks almost standard.

Maurizio Cattelan: In the endless feed, content must be produced or recycled nonstop. Under that pressure, authorship rules fray from exhaustion more than evolution. Everything is accessible, copyable, editable. Today the real plagiarism isn’t copying an image—it’s using it with zero intention. Creativity dies when the gesture turns automatic, harmless, forgettable.

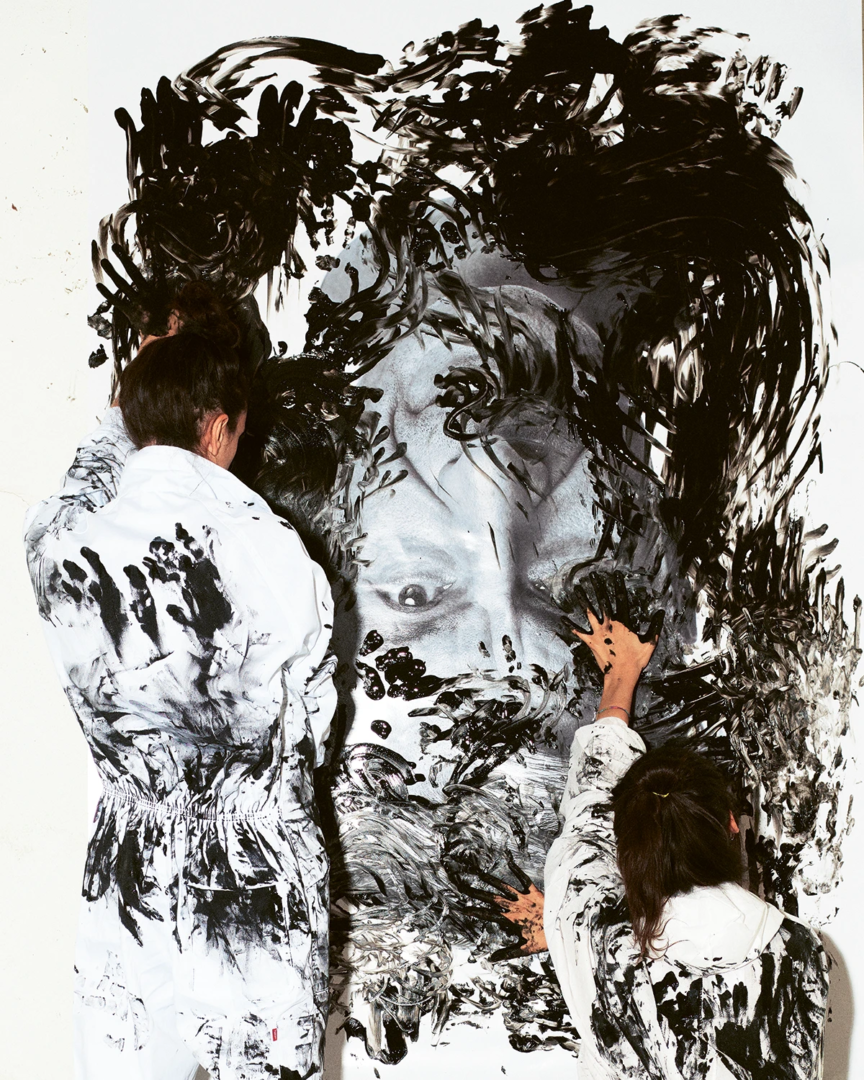

Through surgical page-tearing and Toiletpaper’s viral contamination, Maurizio Cattelan transforms curated images into living consumer objects that escape the magazine page

MM: Back then, your montage process was anything but automatic: every torn page was a deliberate act of selection and violation—almost surgical.

Maurizio Cattelan: Selection always came from respect. We admired those images; they seemed more interesting than their original containers. Montage came next: placing two pages side by side made them talk—sometimes harmoniously, sometimes in tension. No text, no captions. Just images, sequenced so they could start new conversations. It was instinctive yet precise—visual editing tuned to the moment.

MM: With Toiletpaper, the paper object you built with Pierpaolo Ferrari, consumption is faster, yet the images won’t stay put; they migrate from magazine to armchairs, soda cans, shampoo bottles. Soap in the viral sense.

Maurizio Cattelan: Unlike Permanent Food, Toiletpaper feeds a different digestive system. The web made Permanent Food obsolete; feeds stack content like endless magazines. We needed something that could survive saturation. Toiletpaper does—its images escape the page and reincarnate in unpredictable forms. They’re not for contemplation; they’re for use, for consumption, for ingestion.

An interview with Maurizio Cattelan: about disinfecting the art world while the Paris court case reignites debate on artisanship and authorship

MM: Your ironic, often provocative gestures—from Him to the untitled works—seem to operate like disinfectants in the art world, burning yet cleansing, rather than existing as mere spectacle.

Maurizio Cattelan: Irony stings but cleans. It doesn’t seek laughs; it makes space. Certain gestures shock only because the system is anesthetized. Him and others aren’t meant to scandalize but to pry open a crack—just enough for a sideways glance, a doubt. If they turn into spectacle, that’s because audiences prefer noise to the embarrassing silence many works leave behind. That silence is the truest part.

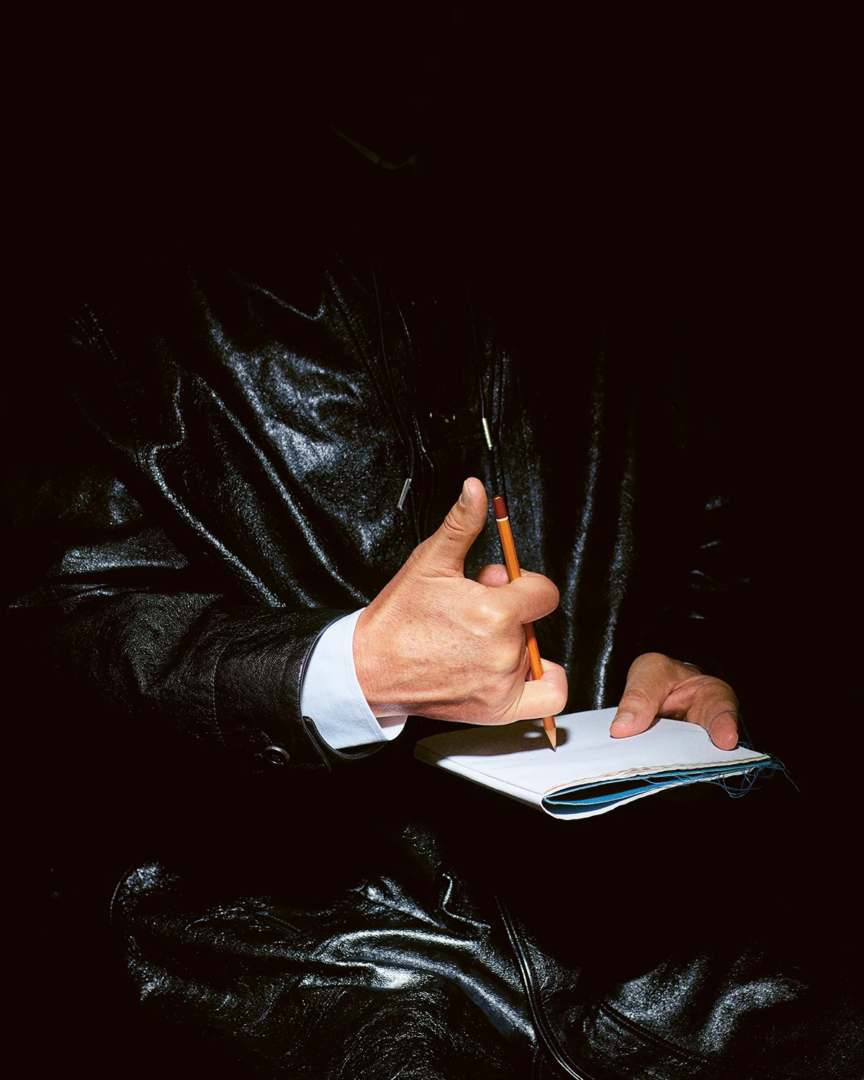

MM: I’m reminded of the 2022 Paris ruling that rejected Daniel Druet’s authorship claim on your wax figures. The debate returned to craft versus concept—where the pristine idea ends and the “dirty” labor begins. You still rely on artisans, don’t you?

Maurizio Cattelan: I’ve never thought an idea could shape itself. Like film, architecture, fashion, or music, you need artisans, technicians, specialists to turn an intuition into something real. No one questions a director’s authorship because a crew shot the movie, or an architect’s because a hundred hands built the tower. Vision lives with the one who sparked it; that vision guides every contribution. Without the idea, there’s nothing to build.

Maurizio Cattelan channels soap-opera seriality and Trojan-horse humor

MM: Soap also evokes the soap opera, a serial form. You acknowledge repetition yet resist calling your own practice serial, even though threads of death, loss, and identity run right through everything.

Maurizio Cattelan: Before reality TV, soap operas showed how to narrate repetition, slowness, uneventful time. Seriality isn’t negative if used smartly. I don’t see my work as serial: each project is born from changing circumstances—place, moment, people. There is a thread, yes—obsessions that return. If that counts as seriality, then sure: I’m a soap-opera artist.

MM: When you talked with Hans Ulrich Obrist, you described humor as a Trojan horse for social critique—a light entrance that carries heavier cargo once inside.

Maurizio Cattelan: Humor and irony always harbor tragedy—they’re two faces of one coin. A good joke hurts. A good joke hurts. Laughter enters lightly, delaying the moment you realize what you’re seeing. When it lands, you can’t unsee it. And if you laugh, you’re already complicit.

Balancing arousal, tension and guilt, Maurizio Cattelan challenges flat digital porn and restores complex desire in visual culture

MM: Back in 2015 you said, “Art isn’t pornography, but it works on arousal.” Your images constantly balance visual stimulus, sexual tension, and guilt so the viewer feels attraction and unease at once.

Maurizio Cattelan: Arousal is a switch, not the destination. Art can use desire without becoming its slave. It’s a space where the viewer feels exposed — half involved, half uneasy. It isn’t provocation for its own sake; it’s about keeping a tension alive: attraction versus rejection, pleasure versus guilt. When that tension persists, the image stops being something merely to look at and becomes a presence.

MM: Digital porn today is everywhere—flat, instant, often a poor substitute for real sex education. You seem intent on restoring complexity—ambiguity, fragility, power—without falling into easy scandal or like-bait.

Maurizio Cattelan: Art doesn’t explain desire; it hands desire back its opacity. Today everything must be explicit, transparent, instant—even pleasure. True desire lives in gray zones: it doesn’t reassure, it doesn’t comfort. Art can still show uncertainty, modesty, unresolved tension. Perhaps exactly where the climax is missing, you find the more authentic spark.

From Vito Acconci’s Seedbed to today’s necessary dirt, Maurizio Cattelan pursues limits beyond shock and censorship

MM: I recall Vito Acconci’s 1972 Seedbed performance—masturbating beneath a ramp as visitors walked above. In today’s context, similarly direct acts might be censored, yet other, digitally mediated works can be even more extreme. When you navigate extreme sex, voyeurism, and modesty, you’re after something more intimate than shock, aren’t you?

Maurizio Cattelan: That scene would likely be censored now because its language is too direct — belonging to a time that’s not ours. Yet equally violent or unsettling works appear, mediated by digital hyper-realism, augmented reality, drone warfare, immersive games, animatronics replaying trauma. Technology can carry even more extreme messages. Art chooses whether to show, to comment, or simply to expose the paradox.

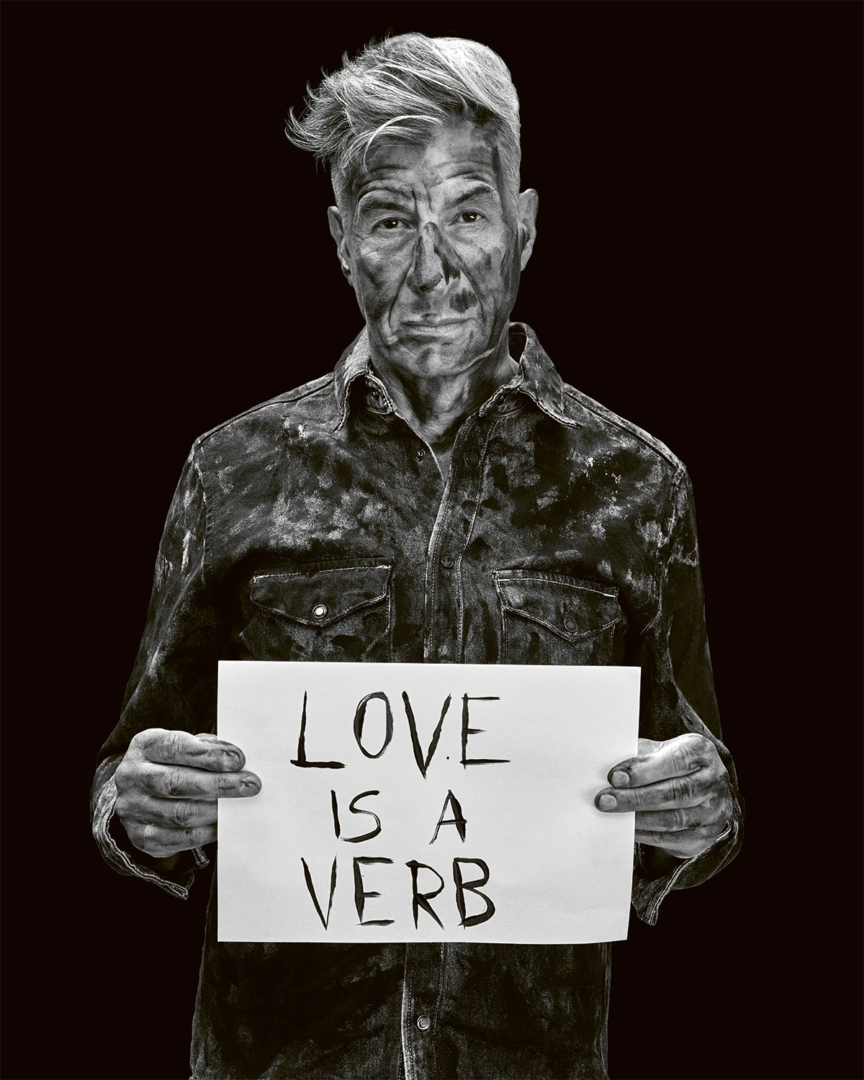

MM: Between cleanliness and what you call “necessary dirt,” what lingering trace do you hope people carry away after they’ve bathed in your work?

Maurizio Cattelan: Art shouldn’t wash anything away. I don’t want people leaving reassured or clutching a moral. If something sticks, let it be friction—a doubt that keeps turning while you’re already elsewhere. Art isn’t here to mend or explain; it leaves you in a state without solutions. It isn’t therapy; it’s an active ingredient. Art doesn’t purify—it contaminates.

Matteo Mammoli

Team

Styling Loreto Mancini, hair Shinichi Morita @EtoileManagement, set design Serenella Parri, location Motelombroso. Thanks to Studio Santaveronica, Chiara Quadri, Martina Cassatella, Alessandro Ulleri, Davide Sargentoni, Giulia Marrix, Matteo Mazza, Alessandra Straccamore, Nicola Bonora