Sofia Zevi: I don’t use Instagram, I don’t need it

As society chases constant novelty, —yet the value of honest endures. Sofia Zevi and the need to be critical, today when everything seems to have to be ‘wow’ on social media

An interview with Sofia Zevi moved to Milan: I don’t have Instagram on my phone. It is hard to be independent

Sofia Zevi: When you have a space, people want to use it and they offer you what they do. If something is not aligned with that, then we won’t do it. We don’t care if people post about our space on social media or not, or if people write about it or not. What is harder is resisting trends. I don’t have Instagram on my phone; I have it on a separate device for the gallery. It is not because I’m not curious, but I want to know exactly what I’m referencing.

It is hard to be fully independent. There are moods and feelings circulating in our environment, and we tend to absorb them. The hardest part for me when I came to Milan was the lack of nightlife. I didn’t realize until I moved to Milan that nightlife is a part of the quality of life. Nightlife is the moment when you meet people and when you create and release energy. That is the moment when culture happens. That kind of energy makes the conversation interesting, whether it is at the nightclub or at my space. It is just about having that dynamic.

Social media are suffocating that energy. With artificial intelligence the risk is that we are all starting to sound the same, write the same, do the same, think the same, because it survives on us feeding it, and the more we feed it the more it learns. If we are all starting to sound the same, then we are all going to feed it with the same thing, how is it going to survive? What is it going to invent?

Interview with Sofia Zevi: Icons of Italian design history (Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Tito Agnoli, Carlo Scarpa et al.) coexisting with newly produced objects

Sofia Zevi: Beauty must be protected. To achieve that, it must be shown. The historical aspect highlights other examples of high craftsmanship. Some of the pieces presented were industrially produced, but in their time, they were not considered truly industrial. They belonged to what was called serie artigianale—produced in several copies, yet still artisanal. When balance is found, the quality remains high. That same harmony when we display objects and compose spaces.

We aim to present things in slightly unexpected ways. For instance, installations from The Back Studio are often expected to appear in a spartan, industrial setting due to the materials used. The strength of these works lies in their ability to integrate into any environment. This is part of the subtlety of beauty—what makes something beautiful is often its quiet adaptability. The Vica chairs appear classic at first glance, their strength is in the details. These chairs have been refined over nearly seventy years: the proportions are exact, and the backrest is angled to provide the ideal balance of comfort for work or reading. People expect to see them in classically modern interiors. We seek tension—we’re drawn to things that are slightly off, not pristine. Without an appreciation for that, one cannot truly understand glass or craftsmanship.

Sofia Zevi on the collaboration with fashion designer Alfa Perro and the integration of her work with that of the other artists and designers

Sofia Zevi: I consider the quality of what Alfa Perro creates so high that I have no hesitation placing it alongside a vase by Akira or a table by Ico Parisi. She is also an architect who, at a certain point, decided to start making clothes—beginning with jackets and coats. Before anything else, she spent a year studying the structure of these garments. She then enrolled in a program at IUAV in Venice. Today, she designs her own patterns and cuts the fabric herself, by hand. She then delivers the cut fabric and patterns to a small artisanal workshop located in Treviso.

The level of research that goes into her work, she cuts the fabric personally, is uncommon. Like Vica’s chairs, her clothes appear simple but are not. Their beauty becomes apparent only when worn—or, in the case of a chair, when sat in—because of the care taken in their design and construction. They feel as if they were made just for you. They are not tailor-made, but they are produced in small editions.

A critical approach in the fashion system

Sofia Zevi: Criticism is needed. There’s a way to express what one thinks, but society must also protect freedom of speech. In the fashion world, the current situation is disheartening. I hope that what is happening in the design world will also happen in fashion—where people, or maybe just a smaller group, will be drawn to things that reflect high quality standards. The fashion industry is under similar pressure. Society’s constant need for new information is unfortunate. At times, it’s hard to keep going—and it’s challenging for Alfa Perro too.

Sofia Zevi: from New York City to Milan, the impulse to open the gallery as a shop

Sofia Zevi: When I lived in New York City my idea was to have a space where I could bring different craft artists from Europe. It was impossible to do it in New York. It is not a viable business model, since spaces are too expensive. When I moved to Milan with my husband in 2020, I still had this fantasy, and I was amazed by the many workshops scattered throughout Italy. At the same time, I became close to Chiarastella Cattana, a textile designer who has a shop in Venice. I wanted to have the same lifestyle that is entailed in owning a shop open to the public and that I didn’t want to work in an office.

The shop would become a way for me to meet new people, which would also help me to start my life in Milan. I use the word shop because at the beginning I wanted my space to be a high-end shop, inspired by other stores such as Arts and Science in Japan, Tiina in Amagansett (New York), and my favorite Song in Vienna. Those are not just stores but meeting points for different artists and curious people. I finally opened my space in 2023. Even today, I don’t like to talk about it as a gallery, even though it looks like one.

Milan and New York: hidden beauty and the notion of luxury

Sofia Zevi: I already knew Milan quite well. It reminds me of New York. People come here to work. If you don’t work here, you don’t understand the city. Whether it is art, design, fashion, or even finance, Milan inspires you, as does New York. The architecture of the facades on the streets suggests that a lot of things are happening in those hidden courtyards. What makes it attractive is the energy of the people, and the diversity.

An interview with Sofia Zevi: the research of the space, the original aspects preserved, and the interventions made to adapt it to the gallery needs

Sofia Zevi: I frequently dined on Via Ciovasso, so I looked for a space on the same street and found one available to rent. The premises—formerly Galleria Seno—still had its original wooden ceiling, painted turquoise by the earlier gallery owner. A later tenant had hidden the ceiling behind false walls and transformed the interior into a white cube. After removing those walls, we revealed the painted ceiling and used it as the starting point for the new palette.

We opted for a dark green for both the floor and the wood cabinets on the walls. The cabinets, designed by Giorgio Mastinu (whose modern-art gallery in Venice resembles a jewel box), break the white-cube effect and give the room flexibility. Since I was just starting out, I didn’t have a huge inventory. I also wanted to be able to display smaller objects and because of the idea of researching the best quality I don’t always have many pieces to show. If we had used shelves, I would have had this pressure to fill them, but with the cabinets we are able to keep them close or open.

Inside, they are lined with Chiarastella Cattana fabric from the collection I Would Like to Be a Painter, inspired by the Viennese artist Dagobert Peche, who was prolific before his untimely death.

The word design has become broad: Sofia Zevi says; the curatorial process

Sofia Zevi: The word design has become so broad that its meaning feels unclear. What stands out in the work of the artists we collaborate with is a high level of craftsmanship —this is why we refer to it as art, not design.

The core values of my curatorial approach are beauty, craft, quality, and creativity. Luxury, in this context, has nothing to do with price or exclusivity. It shouldn’t be something that excludes—it should be accessible to anyone with curiosity.

Sofia Zevi: We make a point of seeking out diverse encounters and go out of our way when something seems interesting. This often means visiting artists in their studios, even outside of Italy. Many artists today face pressure to produce continuously in order to sustain themselves, which can lead to work that feels rushed or superficial. Dedication and intentionality are what I value most in the artists we choose to work with.

Sofia Zevi’s artistic collaborations: Akira Hara, Edgar Jayet, Chiarastella Cattana, and Salone del Mobile Projects

Sofia Zevi: I currently work exclusively with one artist: Akira Hara, a Japanese glassmaker who moved to Venice 25 years ago. For the gallery’s inauguration two years ago, we presented a collection by Edgar Jayet, although we’re not collaborating at the moment. The collection, Unheimlichkeit, was created in partnership with Chiarastella Cattana and was later acquired by the French Mobilier National. Jayet is a French interior and product designer—also trained in architecture—who studied at L’École Camondo in Paris, a rigorous school within the Musée des Arts décoratifs. In their first year, students there work entirely by hand—no software, only drawing and sketching. Jayet collaborates with some of Paris’s most historic workshops and is deeply rooted in traditional craft.

For the 2025 edition of Salone del Mobile, I collaborated with Vica, the furniture line founded by Annabelle Selldorf’s grandmother in postwar Cologne. Selldorf, a German architect based in New York, recently completed renovations for the Frick Collection and the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery. She has revitalized Vica, building on nearly eight decades of history with her own architectural sensibility.

Sofia Zevi’s artistic collaborations: Akira Hara, Edgar Jayet, Chiarastella Cattana, and Salone del Mobile Projects

Sofia Zevi: I currently work exclusively with one artist: Akira Hara, a Japanese glassmaker who moved to Venice 25 years ago. For the gallery’s inauguration two years ago, we presented a collection by Edgar Jayet, although we’re not collaborating at the moment. The collection, Unheimlichkeit, was created in partnership with Chiarastella Cattana and was later acquired by the French Mobilier National. Jayet is a French interior and product designer—also trained in architecture—who studied at L’École Camondo in Paris, a rigorous school within the Musée des Arts décoratifs. In their first year, students there work entirely by hand—no software, only drawing and sketching. Jayet collaborates with some of Paris’s most historic workshops and is deeply rooted in traditional craft.

For the 2025 edition of Salone del Mobile, I collaborated with Vica, the furniture line founded by Annabelle Selldorf’s grandmother in postwar Cologne. Selldorf, a German architect based in New York, recently completed renovations for the Frick Collection and the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery. She has revitalized Vica, building on nearly eight decades of history with her own architectural sensibility.

Sofia Zevi and Back Studio— artists Eugenio Rossi and Yaazd

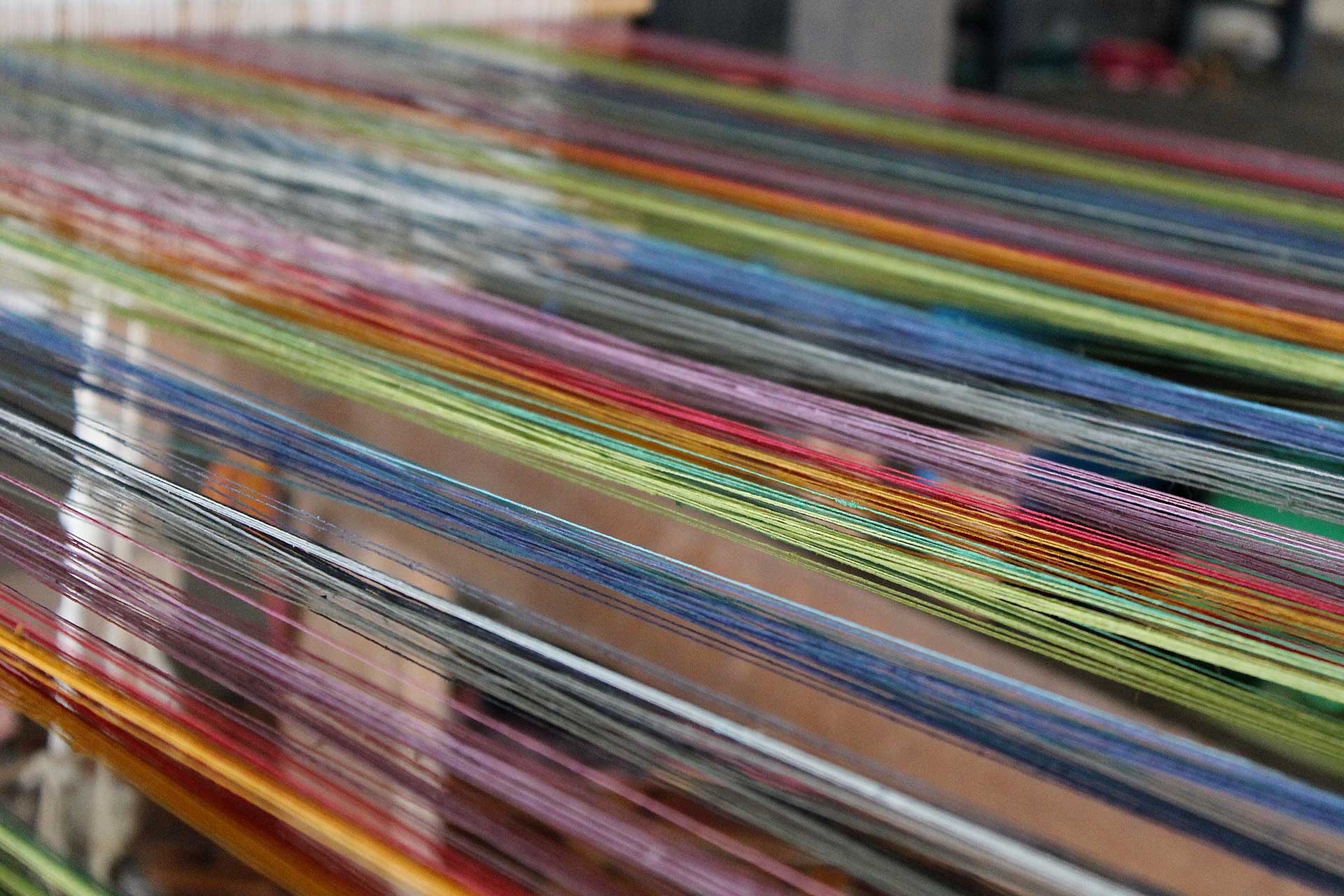

All of the artists I work with have close relationships with historic workshops—often active for a century or more. Akira works with Gianni Seguso, one of Venice’s most storied furnaces. Edgar Jayet collaborates with Declerq, founded in the late 19th century. Chiarastella Cattana sources her textiles from a weaving mill with similar heritage.

The Back Studio—a collaboration between artists Eugenio Rossi and Yaazd Contractor—is an exception. While they don’t partner with a historic workshop, their approach reflects the same depth of artistic commitment. Eugenio assembles his installations spontaneously in his Turin workshop, using an evolving collection of industrial materials sourced from hardware stores. There’s no formal design process—he builds the works intuitively. The neon tubes in their installations are all hand-blown by Yaazd, his partner. Despite the absence of a traditional workshop, the integrity and intention in their process is unmistakable.

Gabriele Della Maddalena