It’s just a t-shirt: from Westwood to rebellion, politics, sex, irony

The T-shirt has never been innocent. Westwood made it a weapon, later designers polished it into branding, and today it balances history, humor and activism

The T-shirt in fashion: The latest one suggests and flirts, no strings attached

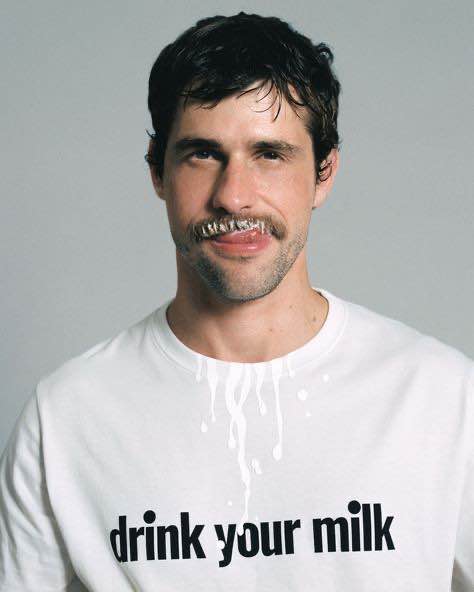

Harry Styles announces his new album wearing a knitted T-shirt designed by Patrick Carroll, the title printed directly across his chest. It’s blue. It’s see-through. It’s tight enough to register ribs, breath, posture. The fabric clings rather than covers, doing most of the talking before the sentence finishes. The slogan floats without declaring, demanding or accusing. It sounds like a suggestion overheard mid-night, half-serious, half-lazy, already dissolving.

The T-shirt works less as a statement than as an atmosphere. Its transparency turns the message into a mere addition to what’s already spoken – the body carries the weight through. Skin visible, chest exposed, softness framed as intention. If there’s a call to action, it’s vague enough to remain frictionless: kiss, dance, drift, repeat. The T-shirt circulates. It slides easily into pop culture, into feeds, into the collective agreement that sexiness today should feel light and wearable.

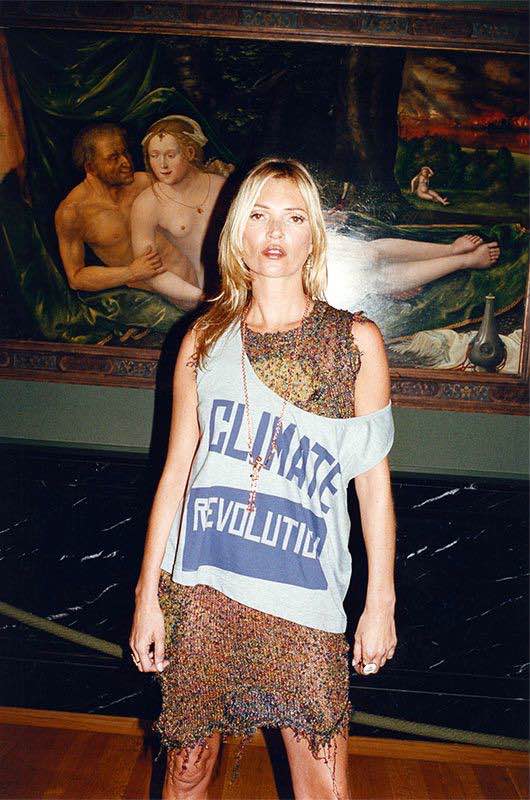

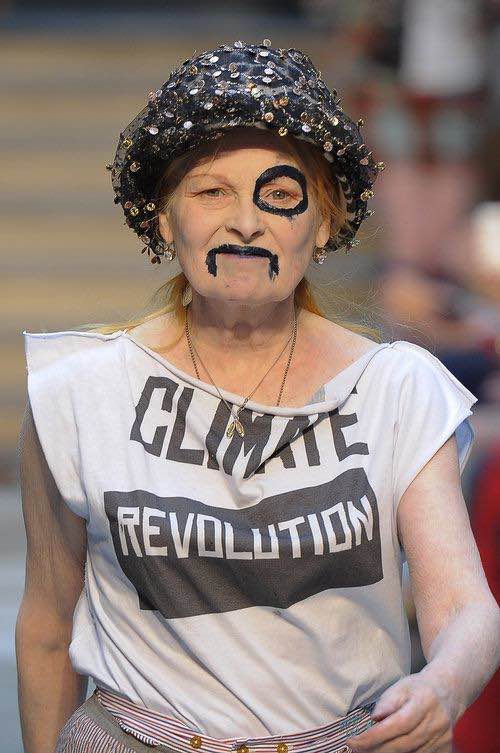

A far cry, or perhaps the logical afterlife, of the printed T-shirt Vivienne Westwood introduced decades earlier, with no vague suggestions but rough demands.

The T-shirt in fashion: A white canvas or a walking billboard

The T-shirt has never been precious. It was designed to absorb sweat – a utilitarian underlayer that’s cheap and washable. Replaceable. The blankness made it democratic. Once the T-shirt moved from underwear to outerwear, it became the most efficient piece that fashion ever produced. A blank canvas, or rather a walking billboard with a pulse.

Unlike other pieces, the T-shirt doesn’t ask for effort. It sits directly on the body and collapses the space between skin and message. A sentence stretched across the chest reads differently from one carved in stone. It’s softer but harder to ignore. This is where the trouble begins. Once language enters something this casual, it gains substance. The T-shirt doesn’t live in galleries or books or subcultures. It moves through streets, clubs, supermarkets, beds. It catches strangers off guard and blends desire with meaning.

The Vivienne Westwood T-shirt: Impolite, unsuppressed, unfiltered

Before logomania turned the T-shirt into the easiest entryway to fashion, it was a by-product of unsuppressed rage and sexuality. The contemporary T-shirt is a natural evolution, softened with time. In the 1970s, it emerged from something far less polite, becoming a weapon in Vivienne Westwood’s hands.

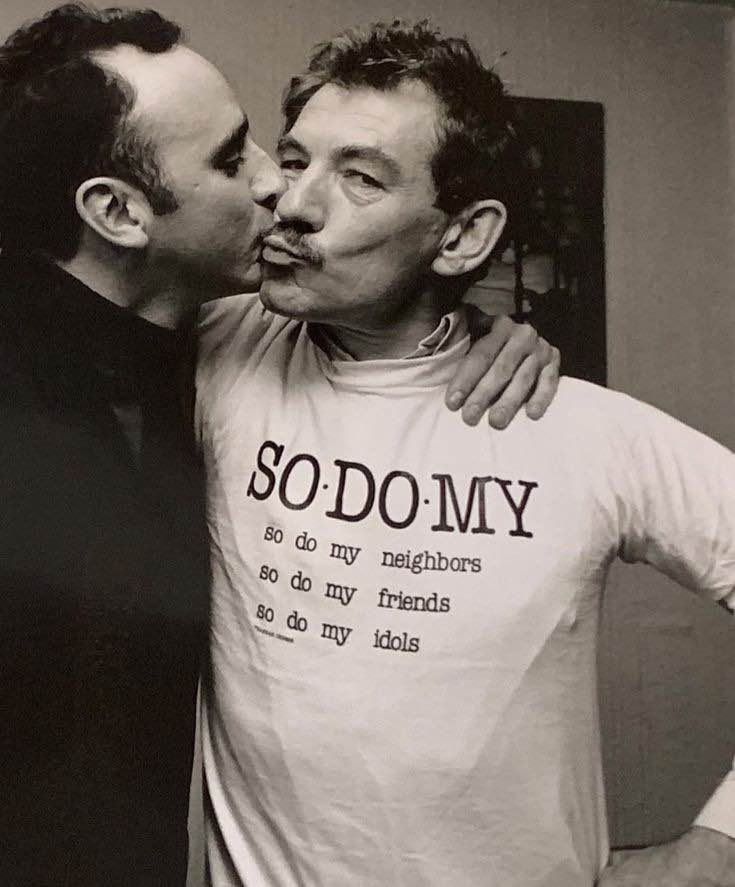

In the early 1970s, fashion was drifting toward ease and optimism. Natural fabrics, loose silhouettes, a collective belief that softness could signal freedom. Westwood rejected this mood. Where others leaned into harmony, she leaned into conflict. Sex, power, politics, obscenity. Rubberwear for the office, read the slogan of the rebranded store on King’s Road, which she renamed Sex. Inside, the space was thick with latex, chains, fetish references, ripped fabrics.

The Vivienne Westwood T-shirt: Cotton, bad cuts, worn on purpose

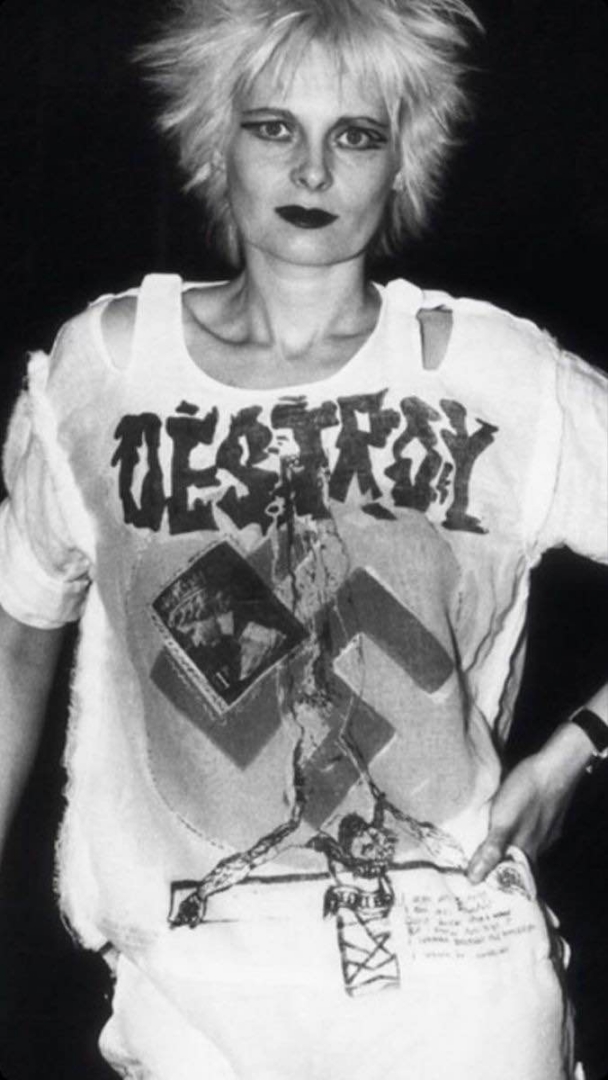

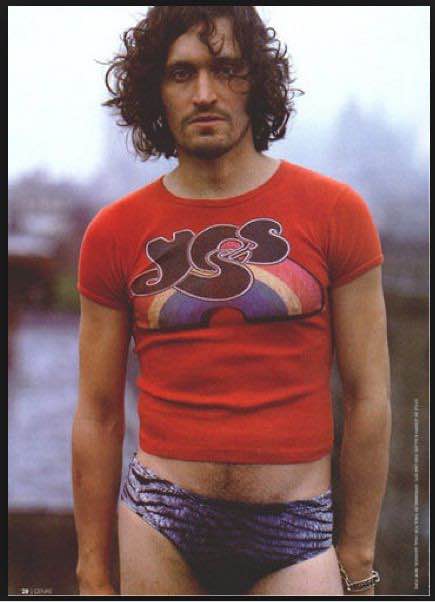

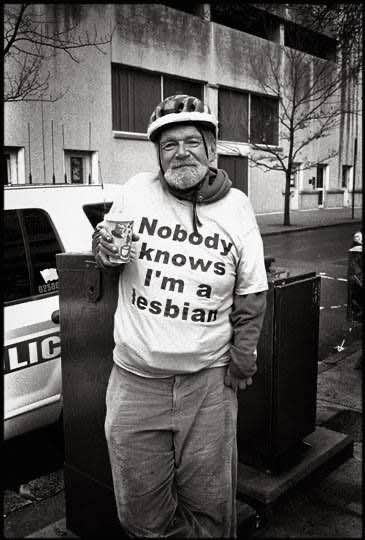

In Westwood’s provocative SEX Shop, the T-shirt appeared. It was materially simple but visually hostile. Mostly cotton, often white or off-white, chosen for good contrast. The fabric aged quickly and absorbed everything – sweat and smoke. The prints were rarely clean. Letters were misaligned, unevenly inked. Nothing suggested refinement, and that was precisely the point.

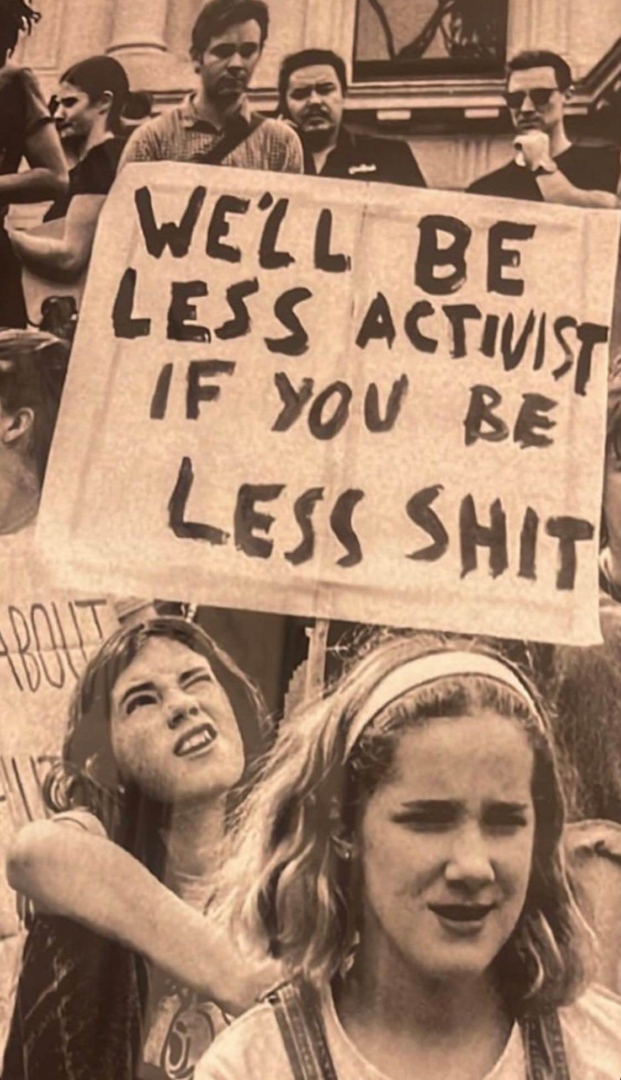

Slogans were unapologetic, twisted with a touch of dark humor. They landed squarely on the chest or stomach, areas already loaded with sexuality and vulnerability. Some shirts were cut, slashed or torn open. Skin appeared where it wasn’t invited. Nipples weren’t hidden. There was no abstraction or mediation when it came to sex and politics. Wearing a Westwood T-shirt always meant accepting that you might be stared at, questioned, insulted or misread.

Westwood’s T-shirt lived in the streets, raw in its immediate impact

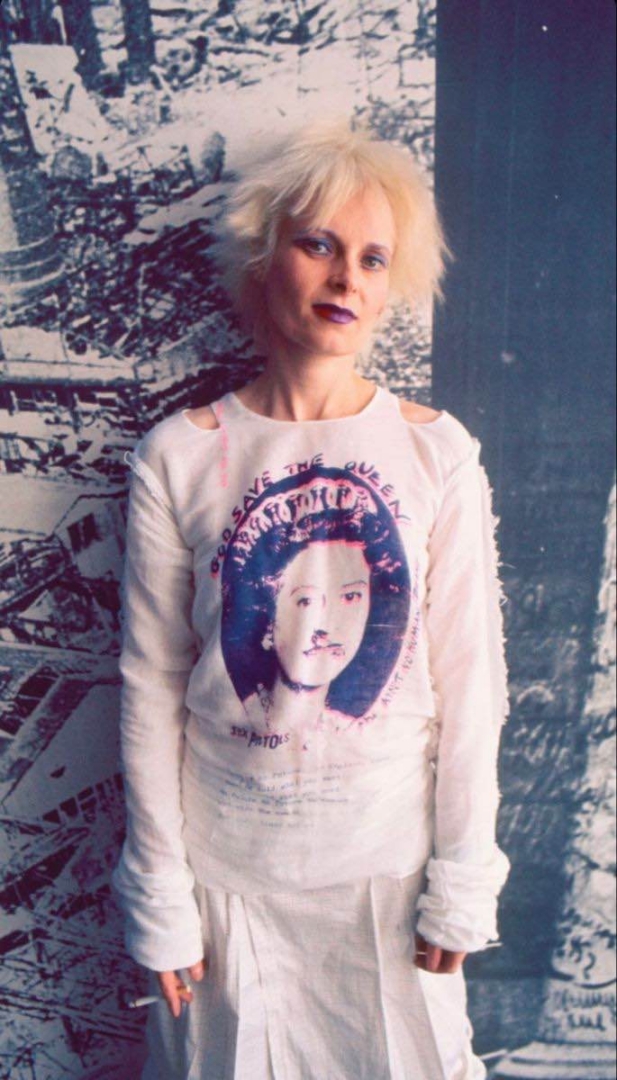

When Westwood created the “God Save the Queen” T-shirt back in 1977, just in time for the Silver Jubilee, it changed the celebration into a direct insult. The phrase itself was already a provocation, but Westwood didn’t stop there. The Queen’s face was defaced, overprinted, pierced by safety pins. The reaction was predictable: outrage, censorship. Yet it became one of the most reproduced images from Westwood’s early years, worn by the Sex Pistols, who had a song with the same title, and everyone else following.

Then there were the shirts from the SEX era that barely bothered with symbolism at all. Explicit language printed across cotton, presented without quotation marks or apology. The slogans as we know today didn’t exist back then.

These T-shirts didn’t live online or benefit from distance and irony. They existed in the streets, clubs, buses. They produced real-life encounters.

How fashion responded to the Vivienne Westwood T-shirt

When Westwood hit the public with her controversial T-shirts, the fashion industry still existed in its own orb, somewhat separate from the political chaos. Once the shock registered, fashion did what it always does: it absorbed and repeated.

In the 1980s, political slogan T-shirts began to move from subculture into visibility. Katharine Hamnett’s oversized tees, with messages like “Choose Life” or “58% Don’t Want Pershing,” made confrontation legible enough to stand in front of power. When Hamnett wore one to meet Margaret Thatcher, protest turned photogenic. The T-shirt still spoke loudly, but it now relied on cameras, headlines and context to complete the sentence.

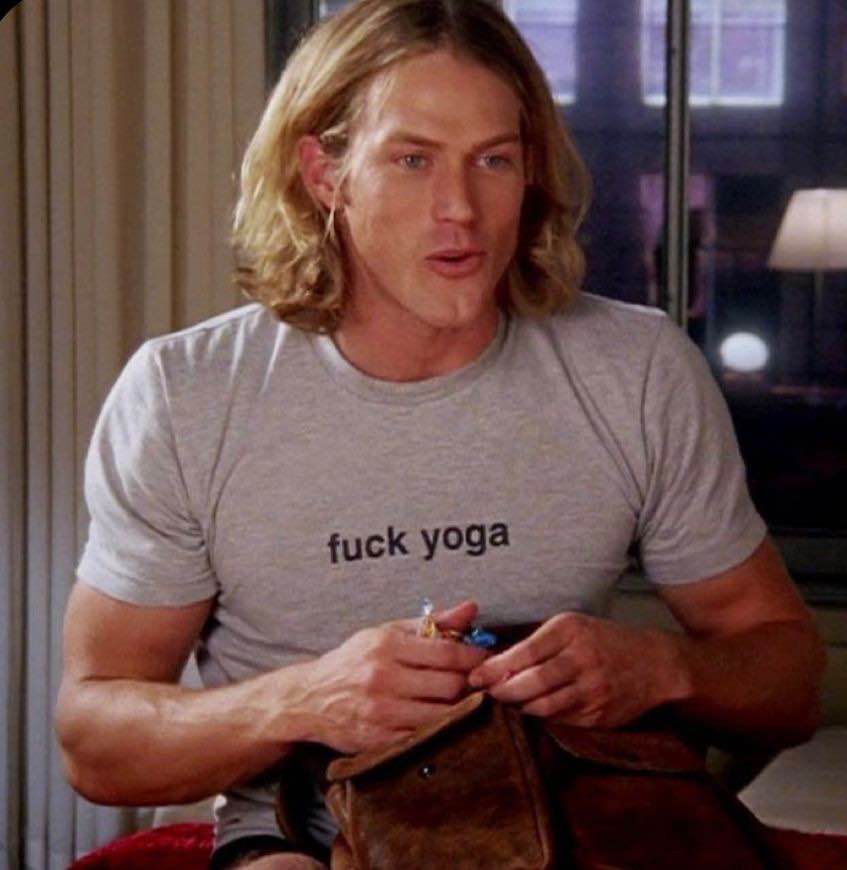

By the 1990s, the T-shirt had become fashion’s preferred form of irony. Jean Paul Gaultier played with language and bodies, placing text on garments that blurred gender, fetish and humor. The shock was still present, but it leaned theatrical. Sexuality was stylized.

The T-shirt in the 2000s: From rebellion to irony, from irony to poetry

In the early 2000s, the T-shirt started to lean toward branding. Dior’s “J’adore Dior” and slogan tees coming after transformed language into luxury. Provocation got lost in translation, and words started to circulate desire. The message was now aimed at the photographer and the archive.

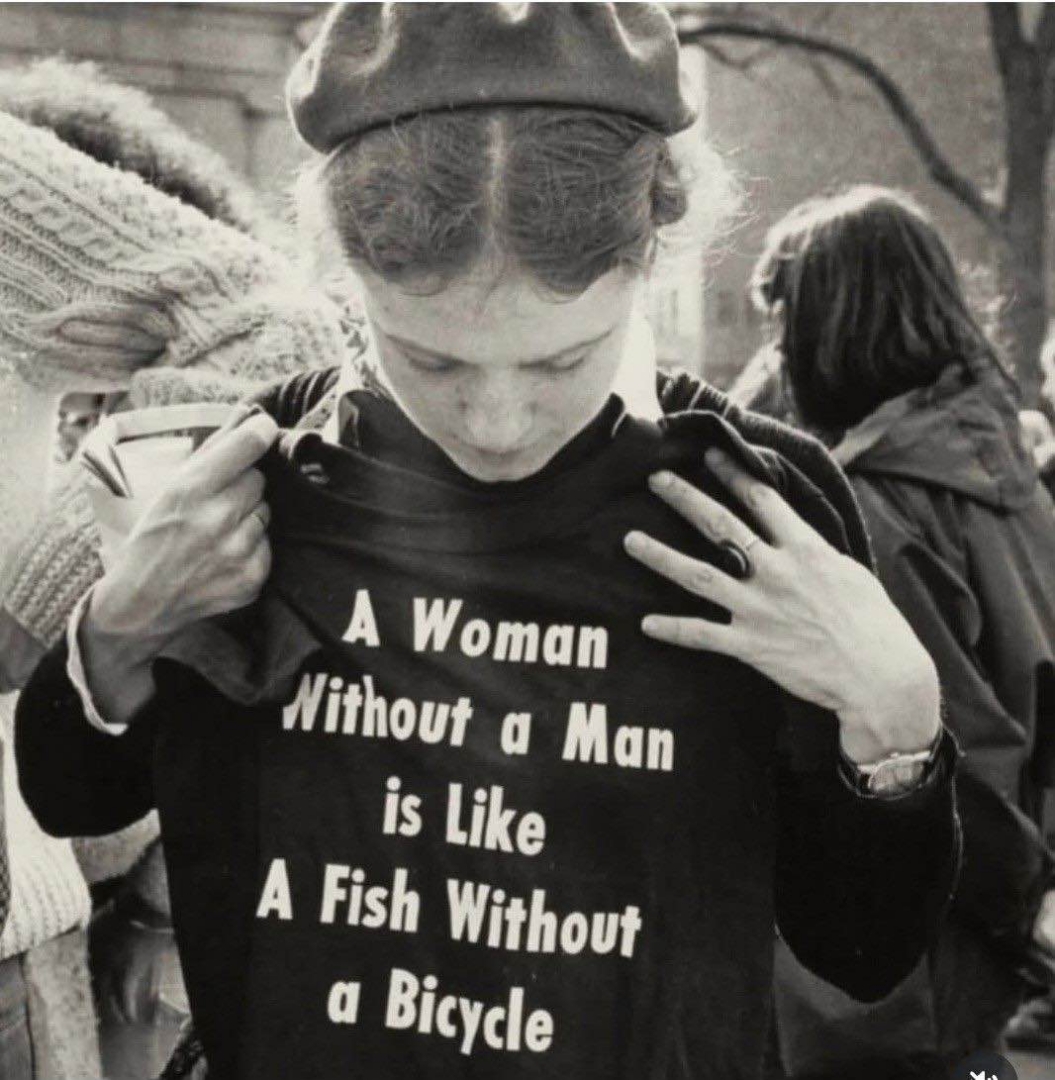

The 2010s pushed the T-shirt further into moral territory. Fashion became openly activist, at least in tone. Slogans about feminism, equality, identity and resistance appeared across runways and fast fashion. The language grew careful, inclusive, unmistakably legible. The risk shifted again. It had to be aligned correctly. At this point, the T-shirt didn’t confront power as much as announce position.

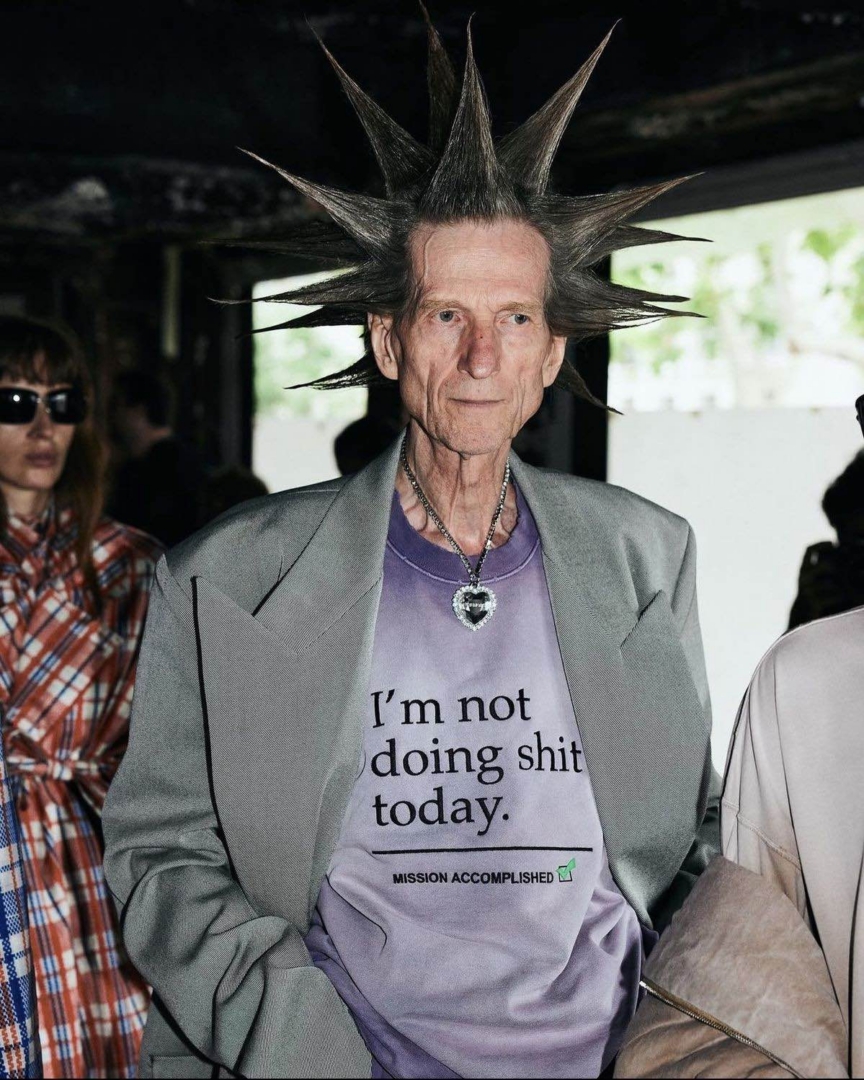

Dior’s “We Should All Be Feminists” hit the runway, further registering the shift toward branding. The message was no longer threatening. It was aspirational and Instagram-ready. By the time the confrontational T-shirts returned, they were priced way too high, and the plot was lost. The “May the bridges I burn light the way” T-shirt by Vetements signaled the shift: irony replaced rebellion.

The T-shirt today is no longer provocative. It’s ready for scrutiny.

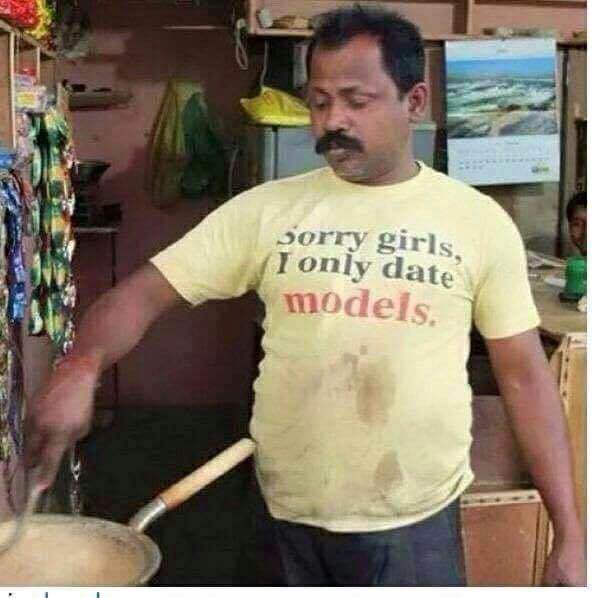

The 2020s made the T-shirt turn inward. The slogan became self-aware, defensive, preventive. The “Nepo Baby” T-shirt seen first on Hailey Bieber was a mere response to online backlash. It didn’t confront a system, but acknowledged it, shrugged and moved on. The slogan was now a comment section flattened into fabric.

At the same time, the T-shirt was turning into a walking press release. Film promotion, pop culture rollout, meme circulation. Slogans are no longer challenging culture but feeding into it. Tees tied to movies and albums are worn by actors and online creators mid-promo, turning body into a walking billboard. In 2024, the “I told ya” T-shirt was seen on everyone, just in time for the promotional period of Challengers. It was deliberately styled off-duty and camera-ready.

What defines the contemporary T-shirt is not its courage but its awareness of consequence. Every word is instantly legible, instantly shareable, instantly judged. Confrontation collapses quickly into discourse. Shock dissolves into content. The T-shirt still speaks, but it does so carefully, knowing it will be answered back.

The Vivienne Foundation revives one of Westwood’s iconic T-shirts

Back in October 2025, The Vivienne Foundation relaunched four of her most recognizable T-shirt prints – Tits, Cowboys, Teddy Bear and Baby Satyr. The project consists of five hundred made-to-order T-shirts, each featuring one of the original designs. Profits go to four grassroots organizations aligned with climate action, anti-war initiatives, human rights defence and anti-capitalist movements.

The revival lands differently in today’s culture. Once designed for provocation, decades later, the T-shirts’ impact comes from contrast. Among the ironic, reactive and promotional T-shirts, Westwood’s vintage graphics feel direct and assert position. The made-to-order format signals this shift. Instead of flooding feeds or chasing visibility, the project limits circulation, asking for intent rather than impulse. The political content isn’t symbolic or aesthetic. It’s tied to where the money goes.

The Vivienne Westwood T-shirt occupies a space of its own, but the power now lies in history, not immediacy. The images still shock, but the shock no longer travels the same way. Cultural reaction has moved online, flattened into commentary, reframed through screenshots and captions rather than physical encounter.

The conditions that once gave these T-shirts their impact – proximity, confrontation, discomfort in shared space — no longer exist in the same form. Outrage is now instant, distributed and quickly absorbed into content. A T-shirt can still circulate, but it rarely lands as an event. It becomes reference, archive, aesthetic.

Susanna Galstyan