Why can’t we recycle car parts? Because they’re designed not to be

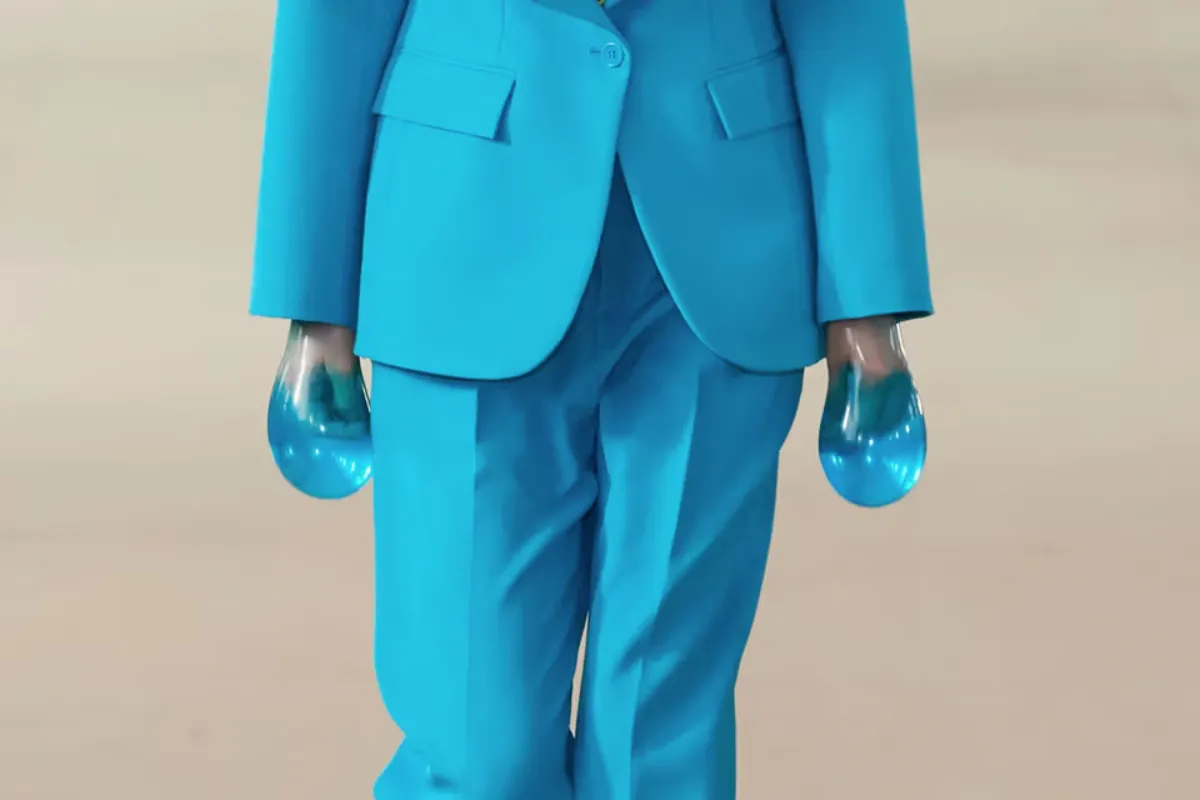

The automotive industry leaves behind a global trail of damage: a residual mix of plastic, foam, glass fibers, and micro-tissues is mostly sent to landfill. Fee-Gloria Grönemeyer reflects on the issue through a series of images for Lampoon SOAP

The footprint of cars: waste, microplastics, and toxic legacy

Roughly 27 million vehicles are retired globally each year. In the EU and U.S., up to 85 percent of a car’s mass, mostly metal, is recycled. The remaining 15 to 25 percent, known as automotive shredder residue (ASR), tells a different story. This residual mix of plastic, foam, glass fibres, and micro-tissues is too expensive to be processed and it is mostly landfilled. It resists decomposition and leaches microplastics and chemicals.

Tire pollution: invisible, airborne, and ocean-bound

Few components are more persistent or more problematic than tires. Engineered to endure, they’re made from synthetic rubber, stabilizers, solvents, and heavy metals. Even in use, tires shed pollution. Every kilometer driven releases invisible particles. A 2016 Pew Charitable Trusts study estimated that one million tonnes of tire dust enter the ocean each year, about 9 percent of total oceanic plastic pollution.

By 2017, a study across 13 countries found that the average person contributes 0.81 kilograms of tire particles annually through driving. That adds up to 3.5 million tonnes of rubber-based microplastics each year: microscopic, airborne, and waterborne. This debris doesn’t just settle. It drifts into plankton, into salmon, into us.

Car interiors don’t disappear: plastic pollution from dashboards and foam

It doesn’t stop at tires. The plastics embedded in car interiors, such as seat foams, dashboard panels, trims, don’t vanish after disassembly. Most aren’t recycled. Instead, they splinter into fragments and infiltrate the environment. These particles range from 500 microns (the width of a credit card) down to less than a nanometre. At that scale, they can breach biological barriers and accumulate in organs.

A 2025 study published in Nature Medicine found polyethylene (PE) and other plastic polymers in human liver, kidneys, and brain tissue. The study compared tissue samples collected in 2016 to those from 2024, showing a marked increase in plastic contamination across all tested organs. In patients diagnosed with dementia, brain plastic concentrations were significantly higher than in healthy individuals.

Plastics in your brain: what research is revealing about car-derived toxins

PE alone accounted for more than 75 percent of all detected plastic—and some of it traces back to cars: fuel tank linings, foam cushions, textured trim. While it’s too early to draw a direct line between microplastics and neurological disease, the scale of accumulation, and its trajectory, is cause for concern.

Why can’t we recycle car parts? Because they’re designed not to be

Why don’t we just recycle it all? Because it’s too complex, too fragmented, and too cheap not to throw away. Cars are built with dozens of plastic types, each with different melting points and chemical properties. A dashboard in one model might be ABS. In another, polycarbonate. These materials don’t blend. Labeling is inconsistent. Disassembly is labor-intensive. Recycled plastic can’t compete with virgin plastic, especially when fossil fuel subsidies keep production costs artificially low.

Car parts are built to endure—not to come apart.

One company at a time: Volz and the slow shift to circularity

Still, there are glimmers of change. Small firms like Autoverwertung Volz GmbH, sponsor of many components used in this fashion story, are rethinking the process. Specializing in careful, piece-by-piece dismantling of end-of-life vehicles, they recover parts that would otherwise be wasted. Their work is precise, valuable, and rare. Without larger systemic support, scaling these circular models is a steep climb.

Global waste, unequal systems: who pays the price?

Globally, car waste is everyone’s problem, but the tools to manage it are not equally distributed.

In many lower-income countries, there’s little infrastructure for safe dismantling, material sorting, or polymer recovery. A 2020 UNEP report found that 40 percent of Africa’s used car imports are over 15 years old. These are vehicles often banned in Europe, sold cheaply abroad, and retired in places with limited waste systems.

Across Southeast Asia and Latin America, car ownership is rising, but recycling remains informal. In the absence of regulation, the burden falls on local workers who burn, dump, or dismantle vehicles with little protection and even less recognition.

Shifting responsibility: who leads the way in car waste recycling?

This imbalance isn’t a question of morality. It’s about systems, access, and accountability. While the global market moves fast, the materials it leaves behind remain. They are local, persistent, sometimes toxic, sometimes invisible. Always someone else’s responsibility.

If some countries are better equipped, technologically and economically, to manage this waste, they are also better positioned to lead. Global investment in recycling infrastructure, harmonized standards, and stronger extended producer responsibility laws could shift the system.

Circularity isn’t just about designing cleaner cars. It’s about building systems that can absorb, reuse, and regenerate the waste they inevitably create.

Text: Fee-Gloria Grönemeyer