Juergen Teller shapes Onassis Ready into a living exhibition: You are invited

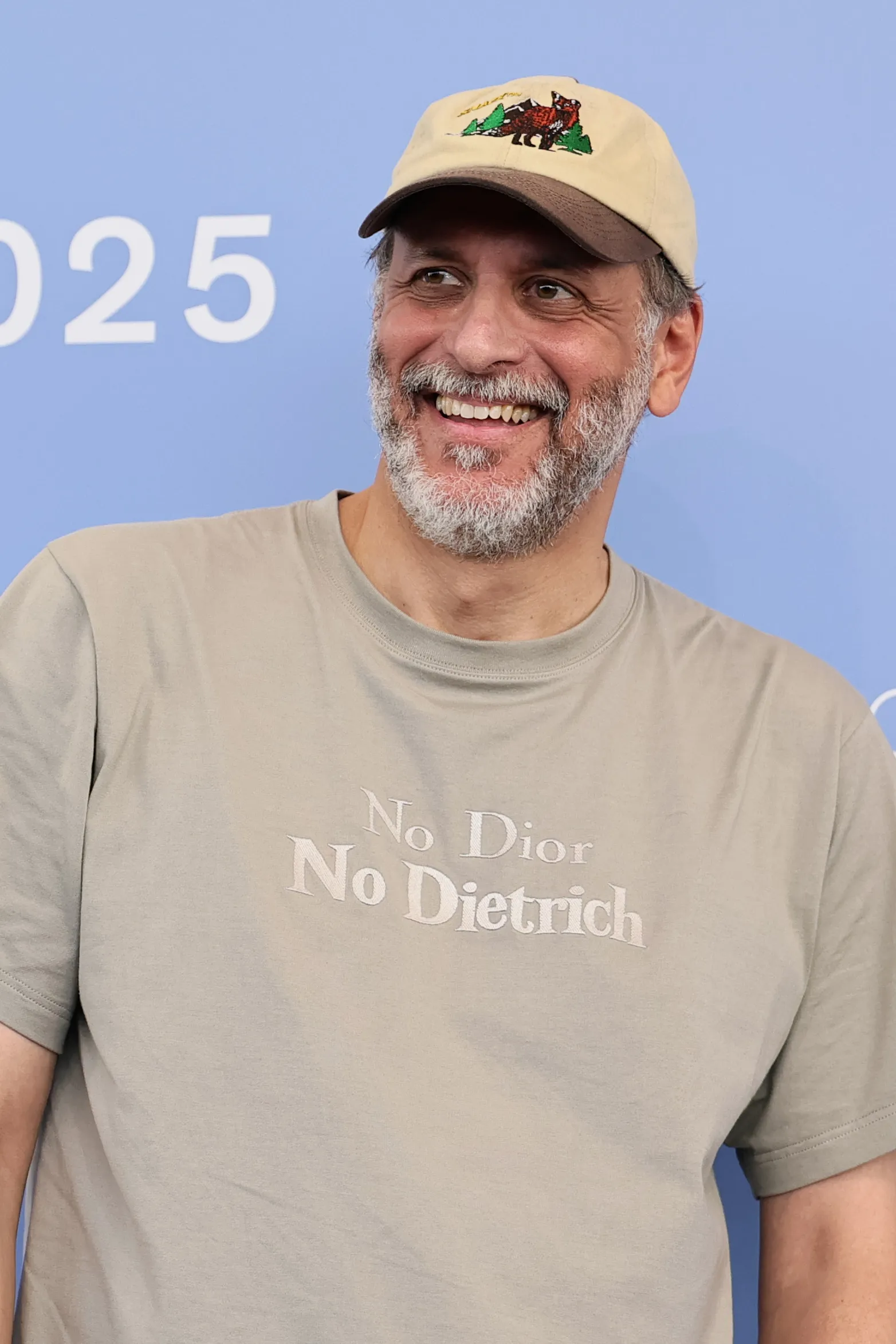

Juergen Teller arrives in Athens not in a white cube: You are invited explores intimacy, archival work and new series within the unpolished framework of Onassis Ready, a former factory turned into a new space

You are invited: Juergen Teller’s solo exhibition is now open in Athens

Juergen Teller presents you are invited—a solo show featuring his selections from previous exhibitions and portfolios, with new, unpublished images, spanning from the 1990s to the present day. From 19 October to 30 December, the industrial district of Athens brings Teller’s past and recent work into a shared, unpolished conversation. Onassis Ready, a former factory turned into a new space of the Onassis Foundation, not only hosts the event but becomes an active participant of you are invited.

Onassis Ready was a factory where things were made, and it still serves the same purpose

Teller’s exhibition inaugurated Onassis Ready in October—the first show Onassis Ready has hosted and the largest solo presentation Teller has staged in Greece. It set in motion the industrial district of Agios Ioannis Renti, a gritty suburb between Athens and Piraeus. The streets are lined with warehouses, workshops, factories and ironworks—a football pitch in the view, with the Parthenon just beyond. An unpolished side of Athens housing leftover infrastructures, the area is less about romance and more about the roughness of creation itself. Here, everything bears the scars of labor, alive in ways that a white cube couldn’t be.

Once a plastic factory, the space preserves its industrial infrastructure, now offering green screens and editing rooms, studios, computers for image processing and AI applications, rehearsal rooms, workbenches, research and experimentation spaces—everything artists need to bring life to their vision. «We like to call it a ‘Factory of Dreams and Ideas.’ To be given time, along with space and money to do whatever you want—this is a dream for an artist,» comments Afroditi Panagiotakou, Artistic Director of Onassis Foundation.

Onassis Ready continues to be a factory where the space itself sets the terms before any artist touches a frame

Onassis Ready is meant to remain a factory. The foundation could have polished it into a conventional cultural space, but it didn’t. The metal beams, open floors, high ceilings and industrial skeleton remain intact. Nothing has been softened or hidden behind decoration. The goal is production. Presentation comes second. Artists are given time and resources to experiment, research and build on their own terms. The space is neutral only in the sense that it serves its function; it doesn’t dictate taste or aesthetics. Its character is active and unyielding, shaping how work is made and seen. Infrastructure comes first. Culture is what happens when the building, the artist and the project collide.

Teller worked with the site, making you are invited a merger of time, space and material reality

Juergen Teller refuses the touring format of identical frames dropped into interchangeable white cubes. He builds each exhibition around the site that hosts it—the structure, the city, the habits. At Onassis Ready, that approach becomes visible in the layout. The show unfolds over two floors and rooms of different proportions, designed with 6a Architects to force a specific circulation. It doesn’t offer a standard neutral vacuum where visitors wander. Every section is adapted to the space, not the other way around. Large images sit next to small ones. Framed works hang next to prints tacked directly to the wall. Themes surface through proximity rather than chronology. Teller’s archival images read differently when grounded in the concrete and metal that once shaped production. Instead of a clean, linear narrative, the exhibition reads like the factory itself—uneven, functional and direct. It builds meaning through installation. No curatorial explanation.

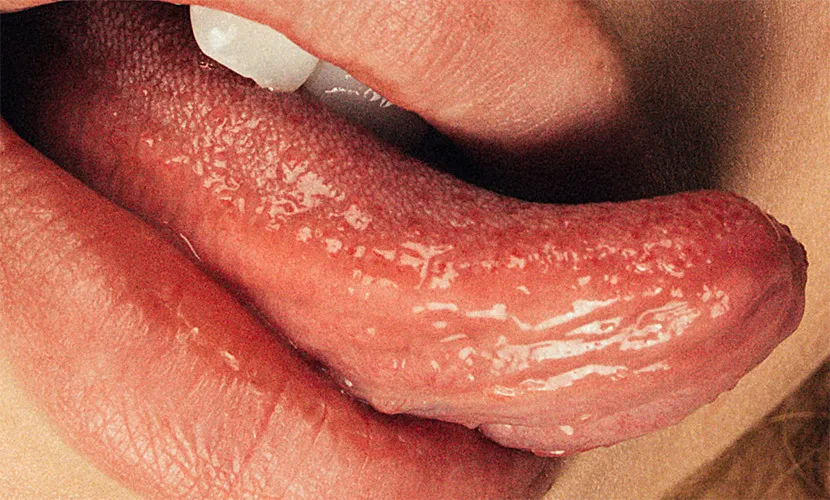

Symposium of Love: Juergen Teller’s series about intimacy in the hardened shells of the factory

The exhibition opens with Symposium of Love, Teller’s newest series referencing Plato’s Symposium. Bodies entwined, gestures casual yet deliberate, people and animals inhabiting sand dunes, tumble through small domestic interiors, or move in shared outdoor spaces. The images are unpolished. No dramatic lighting, no staged theatricality. There’s only presence. Against Onassis Ready’s high, industrial ceilings that dictate the roughness of the space, this intimacy gains a hard-edged clarity. The human warmth of the series contrasts with the factory’s rawness, but the space also amplifies the physicality of the photographs—the weight of bodies, the friction of movement, the material traces of skin and environment. There’s tenderness and resistance. The factory frames the romance without softening it, letting the work exist in tension with the structure that holds it.

Teller places intimate narratives and past commissions side by side, letting the site define their impact

The Myth—a collaboration with his wife Dovile Drizyte—presents fertility, expectation, the traces of life’s cycles. Nudity, domestic gestures, familial connections, ritualistic setups are paired with the building’s industrial skeleton. The factory’s exposed ceilings turn these intimate narratives into something palpable, almost architectural. In proximity, Teller’s older works, family portraits, public commissions like Auschwitz and the Pope, sit in the same unpolished light. Teller captures the intimacy of human life with seriousness and with humor. Against the beams and industrial lighting of Onassis Ready, these works are stripped of reverence or theatricality, read instead as factual traces of a life and career lived and produced. The tension between human vulnerability and industrial hardness becomes the lens through which the exhibition is read. The images don’t dominate, nor does the space. They provoke each other. The environment imposes clarity, spacing and immediacy. It lets both new and old work register through material presence rather than narrative framing.

Teller’s earlier photographs don’t show up as historical milestones either. The exhibition hangs them with the same materials and methods as recent work—they blend in with the new. My Father’s suicide in Erlanger Nachrichten, photographed in the 1990s, is installed next to digital prints from 2023 without hierarchy or chronological separation. The lack of museum-standard climate control and display vitrines keeps all works in the same operational category.

The Path of Hope brings tension between the Teller’s work and the industrial site

The 57-print series changes the atmosphere in the lower gallery space. It’s the only part of you are invited where the architecture is partially softened rather than confronted. Images of Italian churches, ranging from postwar Brutalist structures to Renaissance and Baroque interiors, take over the room. They allow the viewer to read the images without spatial interference. The religious environments are installed in a way that encourages linear progression: visitors move print by print along the perimeter rather than navigating uneven frames.

The shift creates a controlled reading rhythm that contrasts with the factory’s roughness. Instead of competing with the building, the works here mute its presence. The result is a rare moment in the exhibition where the viewer is not negotiating production conditions. It turns the lower gallery into the closest thing the exhibition has to a chapel, produced through hanging logic rather than architectural redesign.

Reuse of factories: How industrial structures shape exhibitions and reduce impact

Reusing industrial buildings like Onassis Ready is a practical solution before it’s an ideological one. The structure already exists. The foundations, concrete, steel and floor plate are in place. No demolition, no new materials, no construction footprint. The building stays in circulation instead of becoming waste. Keeping what works and adapting interior to current needs leaves no need for a new cultural complex with the emissions and financial cost that follow.

Culturally, the reuse of industrial sites avoids blending in with standardized contemporary art spaces—identical glass façades, controlled lighting, sealed surfaces, interchangeable interiors. Artists and curators can’t apply a standard exhibition model. Here, art has to respond to the structure and its character. The factory can change the exhibition concept, but it also responds differently to each show. This alone produces variation.

An industrial building turns into a cultural place with no distress for effect. It’s used because it functions, and each site functions differently. Reuse of spaces like Onassis Ready achieves two outcomes at once—reduced environmental impact and a stronger architectural identity. It doesn’t have to start from zero or become a neutral white cube. It can start with a structure like Onassis Ready—a space that sets its own limits.