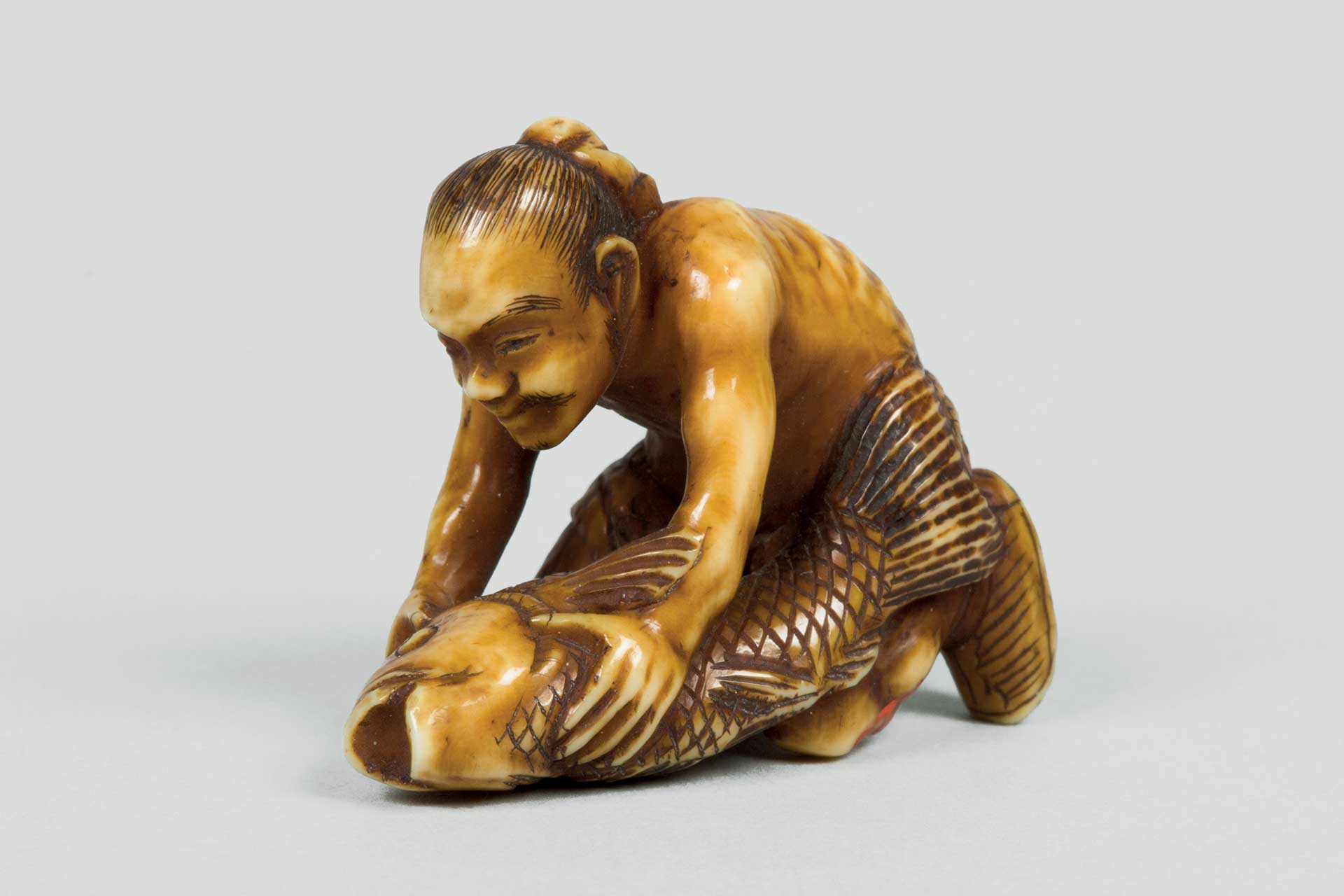

Netsuke: a Japanese art form that needs to be held

Delving into the enigmatic world of Japanese miniature art and its journey from Edo’s floating world to global collectors – the word Netsuke derives from ne ‘root’ and tsuke ‘attach to’

The Art of Netsuke: A Unique Japanese Tradition

Netsuke, from ne ‘root’ and tsuke ‘attach to’, is a Japanese art form that needs to be held. They were purchased similarly to how one might buy cufflinks, with an eye on their appearance. Choosing a shishi indicates a hint of superstition, yet the true value lies in the shishi, not the netsuke.

Historical Context: Japan’s Edo Period

Japan, 1600. General Tokugawa Ieyasu triumphed in the battle of Sekigahara, eliminating the opposition by cutting off some forty thousand heads. In 1603, he was elected shōgun and moved the capital to Edo, today’s Tokyo. The country closed its doors to foreign contact and established strict class divisions: samurai, peasants, craftsmen, and merchants. At the base of the social pyramid were craftsmen and merchants, the latter at the bottom as they did not produce anything. They were called chōnin—citizens or bourgeois. They lived in the ukiyo, the floating world.

There was no cultural elite in Edo; no literati. Stories of the floating world—populated by courtesans, sumo wrestlers, and actors—were narrated in images by craftsmen born in the ukiyo, who had to work for a living. Illustrators were not the only ones who struggled to make ends meet. Leveraging the vanity of merchants and their desire to flaunt wealth, sculptors and engravers in the ukiyo specialized in producing fine accessories that were not valuable enough to be banned by law. These were mainly small containers (sagemono) to be attached to an obi, the sash worn around the waist over the kimono; a drilled pearl, the ojime, holding the cords together, counterbalanced at the other end of the obi by a miniature no bigger than the palm of a hand, called a netsuke—from ne, ‘root’, and tsuke, ‘attach to’.

Accessorizing the Ukiyo: The Merchant’s Choice

Imagine a merchant in the ukiyo selecting his accessories, almost like a dandy. It is easy to conceal sagemono and netsuke among the folds of a kimono, hiding them from curious eyes. If those eyes belong to a beautiful courtesan, however, they can be swung quite coquettishly. Different sagemono serve different purposes—a tobacco pouch, a coin purse, a small writing set, or a medicine holder. These fine cases are usually made of lacquer or ivory, adorned with animal or floral decorations.

The Dual Narrative: Netsuke and Sagemono

Unless the set was commissioned—a rare occurrence—netsuke and sagemono told two different stories. They were purchased separately and balanced each other according to Zen principles: on one hand, the nobility of lacquer; on the other, the irreverence of the button. The netsuke that have survived to modern days are mainly of three kinds: round flat manjū, small round katabori sculptures, and sashi, elongated and fine. The most popular materials included ivory, wood, and horn, though exceptions existed—amber, for example, or coral, toucan beak, and tortoiseshell. Much depended on the imagination of the netsukeshi, along with the availability of materials. A wide variety of subjects emerged: men, animals, plants, mythological and fantastic beasts. Favorites included shishi, the Chinese guardian lion; shoki, the less than fearsome demon queller; and Okame the peasant, who danced to entice the sun goddess out of the cave where she was hiding. Then, in the mid-nineteenth century, it all unexpectedly ended.

Commodore Perry: The End of an Era

The Commodore of the United States, Matthew Perry, sailed to Japan with four warships—their color and thick, dark smoke earning them the name “the Black Ships.” The aim was to force trade relations with the West upon a Japan that inevitably had to agree. The twelfth shōgun of the Tokugawa dynasty died just a few days later—reportedly due to the pain. In 1854, the Treaty of Kanagawa sanctioned the reopening of the ports, and Western culture poured into Japan, marking the beginning of rapid modernization. Western clothing, complete with pockets, replaced the less practical kimonos. Wallets, purses, and cigar holders eliminated the need for sagemono and, consequently, their counterweights, the netsuke. Meanwhile, for European and American high society, it was love at first sight for these tiny statues. The craftsmen in the ukiyo were eager to sell them, as they were nearly impossible to sell in their home country.

The Legacy of Netsuke: A Collection of Western Interest

Today, the most important netsuke collections are found in the West, with the British Museum owning a remarkable assortment of more than 2,100 pieces, acquired over the centuries. Giuseppe Piva operates a Japanese art gallery in Milan. I meet him for an interview on two topics: the material and symbolic value of netsuke.

The True Value of Netsuke

I had various preconceived notions on the subject. “The material value of a netsuke depends neither on its age nor the material it is made from. Some producers are obviously more important than others, yet what truly counts is the quality and beauty of the netsuke.” I attempt to point out those I consider the most beautiful in his collection. Epic fail. “Only experience can help you here. However, even collectors and their evaluations are often unexpectedly surprised by auction results. I recall an amazing one in Cologne last year, where the selling price was double or triple the initial evaluations. I remember a netsuke in ivory—a foreigner with a rabbit—a Dutch sailor in a French Navy uniform, with trousers fastened diagonally by agate buttons; a truly unique piece. The starting price was 26,000/30,000 euros, but the bidders went mad, and it finally sold for over 200,000 euros. The netsuke sold for the highest amount at auction that I remember was an ivory deer by Okatomo, one of the best-loved creators. It went for 216,000 euros in 2011 in London.”

Reconsidering Symbolic Value

Even my notion about the original symbolic value of the netsuke was incorrect. I was convinced they were tokens or amulets for their owners, whereas the Japanese in the Edo era would never have dreamt of attributing such value to their buttons. “They bought them like we would buy cufflinks, focusing on their appearance. Obviously, if they chose a shishi, they must have been a bit superstitious, yet the value lay in the shishi, not in the netsuke.”

I admit that I am difficult to convince. I feel almost disappointed. I ask Giuseppe Piva if I can at least hold one of his netsuke, and he permits me. This is the real magic: holding one in your hand. Listening to its owner talk about the piece he had weighed in his hand the previous evening in a restaurant. “A subject I had never seen before, a demon on top of a hat, pointing to the tip of the sword of the shoki underneath the hat.” He even shares a small regret regarding a missed special appointment. “I am a member of the International Netsuke Society, and they organize a day when each member can touch a netsuke from the collection at the British Museum. I only discovered it was limited to a lucky few when I was already on the plane. I could have held a wonderful one in my hand: a sleeping mouse.” He shows me the piece in the catalogue.

An Enlightening Experience

As I leave the gallery, one realization stands out. I seek confirmation in The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance, the 2010 masterpiece by Edmund de Waal—writer, potter, art historian, and alchemist. In the middle of the book is a collection of 264 netsuke that belonged to Charles Ephrussi—a Jew, dandy, art patron, and collector—who inherited them to the author, prompting him to reconstruct their story.

The story of the objects is crucial, not of the people who owned them or the sentimentalism attached to them. “Melancholy is a sort of default vagueness, a get-out clause, a smothering lack of focus. This netsuke is a small, tough explosion of exactitude. It deserves this kind of exactitude in return,” writes de Waal. As the collection’s story unfolds, he discovers two essential truths. First, inheritances cannot be separated from their sentimental value. “The way in which objects are handed down is pure narration. I’m leaving you this because I love you. Or because someone else left it to me. Because I bought it in a special place. So that you can take care of it. So that it complicates your life. So that it will make so-and-so mad with envy.” The second truth: objects hold the ghosts of those who loved them. It is vital for us, as receivers, to touch them in turn. As Westerners, we are sentimental. We will not fall in love with a netsuke until we hold it.

La Galliavola Arte Orientale: A Treasure Trove of Netsuke

La Galliavola Arte Orientale gallery exhibits hundreds of ancient netsuke, as well as Chinese porcelains and lacquers, Chinese and Tibetan bronzes, paintings, jade and hard stones. The gallery first opened in the early 1980s with Patrizia Chignoli, a scholar of oriental art. Since 2001 it has been run by her husband, Roberto Gaggianesi, and daughter, Carla. Since April 2007, La Galliavola has been publishing the quarterly bulletin Netsuke.

[envira-gallery id=”28193″]