Are the new creative directors interested in sustainability?

A retrospective on whether and how the new creative directors are addressing sustainability – from small independent brands to major fashion houses, from Duran Lantink to Balenciaga

The new creative directors debuting at the upcoming fashion week: are they interested in sustainability?

We all know this well. Matthieu Blazy, fresh out of Bottega Veneta, and his first collection for Chanel. Earlier this year, Louise Trotter stepped into Bottega Veneta following Blazy’s exit. Over at Givenchy, Sarah Burton, fresh from her long time at Alexander McQueen, took over the French house back in September 2024. The same time period saw John Galliano’s departure from Maison Margiela. Glenn Martens inherited Galliano’s role, after redefining Y/Project and keeping on shaping Diesel’s review.

The point of all of this is one only: the true measure of the ‘new era’ will depend on whether these shifts translate into verifiable changes in materials, processes and systemic responsibility across the industry.

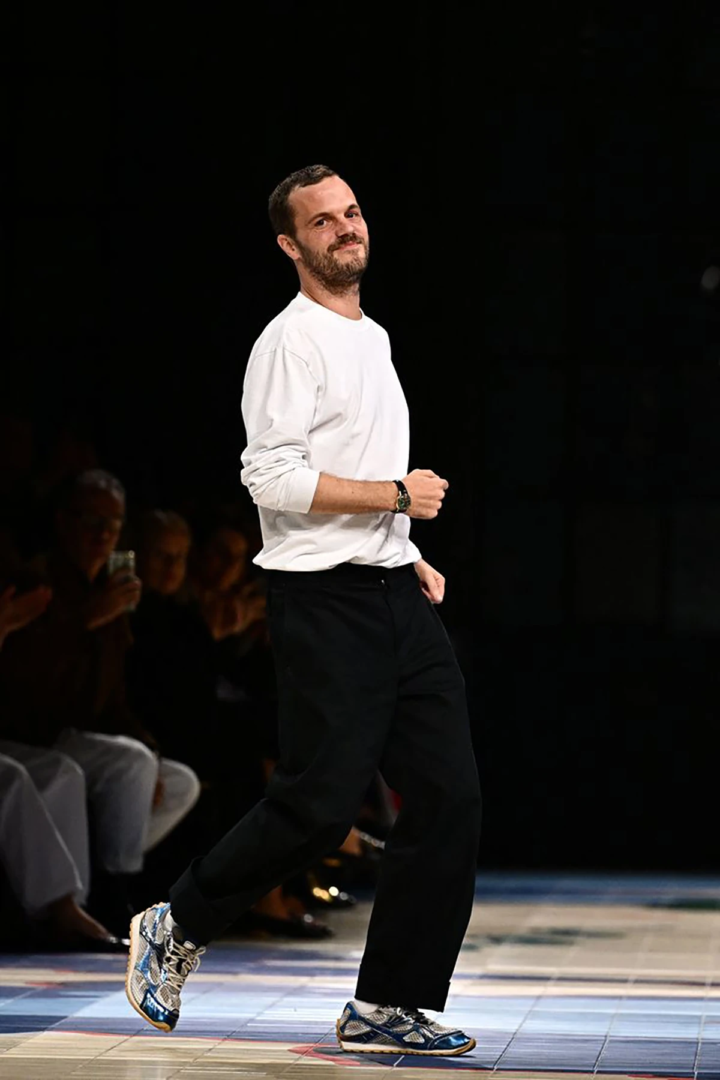

Duran Lantink at Jean Paul Gaultier: New permanence in the brand’s creative direction

Earlier this year, Jean Paul Gaultier named Duran Lantink as creative director—a move towards stability after operating under a rotating guest-designer model since Gaultier’s retirement from ready-to-wear in 2015 and couture in 2020. Yes, Lantink stepped in with an experience that fused an avant-garde vision. Growing up in the Hague, Netherlands, his early art-focused education set the stage for a career driven by bold concepts. He studied fashion at the Amsterdam Fashion Institute before expanding his avant-garde vision at Gerrit Rietveld Academie and the Sandberg Instituut, graduating with a master’s degree in 2017.

His breakout moment came in 2018—that’s when Janelle Monáe wore his infamous ‘vagina’ trousers in the PYNK music video. It cemented his reputation for playful, socially conscious design. Lantink launched his own Amsterdam-based label in 2019, but the pandemic postponed the first show—it took place at Paris Fashion Week in March 2023. Same year, he won the Andam Special Prize. The following year, Lantink was awarded LVMH’s 2024 Karl Lagerfeld Special Jury Prize.

Often built from upcycled or repurposed garments, Lantink’s designs challenged norms of luxury fashion—a merge of sustainability with sculptural, wearable art. From the very beginning, the Dutch designer’s label used excess stock—unsold garments, deadstock fabrics, pre-loved pieces from bigger houses. These became materials for hybrid or collaged garments. 2020 saw the Ellery x Duran Lantink collaboration, built entirely using archival Ellery pieces—around 150 pieces. No new fabrics used.

The designer has also worked with Browns on capsules constructed from unsold luxury inventory sitting in storage. He has introduced a customer alteration service: buyers can return garments for reworking into something new, extending each piece’s life cycle. In his own collections, he has experimented with 95% upcycled fabrics—vintage lace, recycled nylon, lycra, denim, supplemented only by small amounts of new, hand-knitted wool. His International Woolmark Prize 2025 collection drew from recycled military sweaters and traditional Dutch knitting techniques.

Are the new creative directors interested in sustainability? Louise Trotter joins Bottega Veneta

Louise Trotter’s work has often circled around themes of longevity and reuse, though with uneven results. At Carven, she moved away from spectacle-driven fashion toward modular coats, neutral palettes, and pared-down silhouettes. The strategy aimed to extend garments across seasons and reduce overproduction through smaller runs. Yet there was no disclosure of recycled materials, supply-chain oversight, or measurable impact on resources such as water, carbon, or energy. Sustainability remained an implicit narrative, not a documented practice.

At Lacoste, the experiment became more visible. In 2020, she introduced CrocCouture, an upcycling capsule built from archive stock, unsold inventory, and surplus fabrics. Reassembled polos, sweaters, and outerwear were positioned as a circular design initiative, but stayed within the limits of a short-term capsule. The rest of the brand’s production continued to rely on conventional supply chains, with no sign of systemic change.

Are the new creative directors interested in sustainability? Demna Gvasalia: the debut at Gucci

Where Trotter works toward polish and controlled functionality, Demna works through rupture—deconstruction, irony, and reassembly. The runway became a platform for socio-political commentary as much as for fashion. Demna’s work at Vetements set an early precedent with upcycling and reworking vintage garments—most visibly in the Fall 2015 show, where reconstructed Levi’s and t-shirts were put on the runway. The label engaged in collaborations framed around reuse and recontextualization of mass-market clothing.

At Balenciaga, the sustainability focus has been material-driven. The Spring/Summer 2021 collection used 93.5% certified upcycled plain materials and 100% certified bases for prints. The brand adopted organic cotton, recycled polyester, and upcycled leather into seasonal collections. In 2022, Balenciaga introduced Ephea, a non-toxic mycelium-based alternative to leather, applied to outerwear. The same year saw the launch of sneakers made from Bananatex, a textile derived from banana plant fibers, positioned as biodegradable, antibacterial, and waterproof.

Are the new creative directors interested in sustainability? The debut of Pierpaolo Piccioli at Balenciaga

Pierpaolo Piccioli succeeds Demna in Balenciaga’s creative direction— the news raised eyebrows earlier in 2025. A connoisseur of radical elegance and feminine silhouettes, he now faces a challenge in a house defined by Demna’s conceptual, disruptive legacy.

Piccioli at Valentino oversaw the rollout of fully redesigned packaging using recycled paper, cotton, bamboo fibers. They launched the Sleeping Stock initiative, which redirected over 22,000 meters of dormant haute couture fabrics into resale and training projects. The brand advanced traceability, with more than 70% of key raw materials tracked across the supply chain. Valentino’s sustainability reports, supplier summits and inclusivity certifications further tied his creative leadership to measurable progress.

Are the new creative directors interested in sustainability? The debut of Matthieu Blazy at Chanel

From internships at Balenciaga under Nicolas Ghesquière and with John Galliano to joining Raf Simons’s menswear team, Matthieu Blazy’s career began rooted in craftsmanship and couture discipline. He then became the design director at Maison Margiella Artisanal—a space where he honed his ability to merge technical excellence with conceptual vision. At Céline under Phoebe Philo, then at Calvin Klein under Raf Simons, his next roles developed his sharp minimalism and the vision of blending American codes with European precision. But the turning point was Bottega Veneta.

At Bottega, Blazy introduced a sculptural approach to leather, making it pliable, playful, unexpectedly modern. His trompe-l’œil denim and cotton pieces, crafted entirely from leather, turned craft into both a technical feat and a cultural statement. Stripping away logos, pushing Bottega into a space of material innovation beyond aesthetics, Blazy underscored durability. Pieces designed to last, with artisanal techniques repositioned for contemporary wardrobes.

Extending product lifecycles: Sleeping Stock, archival re-releases and repair programs

Blazy’s relationship with material, specifically leather, proved to be innovative for Bottega—creatively. As for the direct tangible results, his approach to leather, beyond trompe-l’œil illusions, emphasized durability and respect for the material. Supple skins treated to mimic everyday fabrics were meant to be worn and re-worn, not cycled out in a season. Under his direction, Bottega initiated its Sleeping Stock project, repurposing dormant textiles. The brand registered growing use of recycled fibers during the same period. In 2022, the brand announced the Bottega Series archival re-release, selling past designs at full price to extend product lifecycles and avoid discount waste. The house began work on a lifetime warranty programme to guarantee repairs and keep products in use longer.

Blazy’s collections expanded the use of material manipulation of leather, developing leather that mimics flannel, denim, or knit, and even leather thread for socks. It showed experiments with one primary material rather than diversifying into lower-impact textile alternatives. In 2024, the launch of the fragrance line incorporated packaging made with Verde Saint Denis marble, wooden caps and eco-labeled, reusable boxes.

Are the new creative directors interested in sustainability? The debut of Jonathan Anderson at Dior Women

Jonathan Anderson. His past roles, shaping Loewe with minimalism, upcycling, artisanal experimentation, could have clashed with a house steeped in heritage and couture tradition. Yet, his first collection proved otherwise: a negotiation between craftsmanship and conceptual play.

After graduating from London College of Fashion, the Irish designer launched JW Anderson back in 2008. The label was a challenge for the industry standards with Anderson’s multidimensional approach to clothmaking. Men’s silken tunics trimmed in lace, gender-fluid pieces, layered silhouettes—his early collections felt like a quiet rebellion against traditional menswear codes. From 2013, Loewe became his laboratory of experimentation, drawing strong reactions from the public. It was then followed by an embrace. From reimagining the Puzzle and Flamenco bags to rejecting the polished finishes, he pushed the narrative of the ‘materials that remember the hand.’ His presence at Loewe was, in fact, a new era for the brand.

At JW Anderson, the focus on ethical responsibility has been conceptual: collections occasionally highlight upcycling or playful reuse of materials. There’s little evidence of a structured environmental program or traceability work.

From surplus experiments at Loewe to Dior’s broader sustainability framework

At Loewe, the results are more concrete. The Fall/Winter 2020 collection, named Eye/LOEWE/Nature, relied heavily on repurposed and surplus materials: recycled polyester, organic cotton, deadstock fabrics, old military tents and quilts. It was followed by the 2021 Surplus Project—the brand turned leftover scraps into woven bags to cut down waste from production. Anderson invested in traceability and artisan support as well, with the Craft Prize indirectly encouraging slower, craft-based production. Some collections experimented with living plants and biodegradable treatments. The Spring Summer 2023 menswear show was a blend of nature and technology. The collection, designed with bio-designer Paula Ulargui Escalona, features hoodies, jeans and shoes with cats wort and chia cultivated on them. More conceptual, the idea was that the pieces eventually merge with nature.

In 2022 at Milan’s Salone del Mobile, Loewe led, by Anderson, presented the Weave, Restore, Renew project, an installation centered on repair and reuse. The project included 240 damaged Spanish baskets restored with leather cord, alongside new works in coroza straw from the Philippines and Korean paper-weaving jiseung. It functioned as a material case study in restoration, highlighting traditional techniques applied to existing objects. It framed restoration as part of design practice, embedding circularity into the cultural discourse of a fashion house.

At Dior, the stage is bigger, the expectations are sharper. The house has already invested in regenerative cotton sourcing, circularity research, decarbonization targets under LVMH. Anderson now inherits this framework. The question is whether he will stay with one-off experiments in surplus use and upcycling, or if he will embed those instincts into Dior’s broader supply chain and scale.

Are the new creative directors interested in sustainability? The debut of Lazaro Hernandez & Jack McCollough

While Loewe thrived under Jonathan Anderson’s craft-heavy surrealism, the duo Lazaro Hernandez & Jack McCollough behind Proenza Schouler’s urban sensibility is now expected to streamline Loewe into a more pragmatic, less experimental model.

The Parsons graduates launched Proenza Schouler back in 2002. For over two decades, they merged intellectual design with commercial wearability—leather satchels, structured dresses, ready-to-wear that consistently delivered retail impact. They introduced recycled fabrics, responsibly sourced wools and certified leathers, often framed as incremental progress rather than systemic change. The collections leaned on durability and timelessness, but supply chain transparency was minimal.

In 2021, Proenza Schouler introduced the Core Collection, a seasonless line centered on sustainable fabrics and wardrobe staples. The debut included T-shirts, knitwear and tailoring made from eco cashmere, eco superfine merino, eco cotton, upcycled wool and deadstock materials from prior archives. Fabrics first used in the Spring 2018 collection were included. Upcycled wool culottes, blazers and carrot pants followed as part of the pre-spring 2021 assortment. The collaborations with eco-conscious projects hinted at awareness but never formed a core brand identity.

Sustainability through heritage and longevity: Veronica Leoni and Simone Bellotti

At Calvin Klein Collection, Veronica Leoni reintroduced the line with structured tailoring, sculptural dresses, and neutral palettes. Documented sustainability actions are minimal: no evidence of recycled or low-impact fabrics, no upcycling initiatives, no circular programs. The closest sustainability angle is durability—archival continuity, neutral palettes, and silhouettes designed to be worn across multiple seasons.

Simone Bellotti applies a similar strategy through archival reliance. At Bally, he reintroduced designs dating back a century, framing them as long-term staples. At Jil Sander, continuity and precision follow the same path: restrained tailoring and heritage silhouettes. No systemic sustainability measures are tied to his work—no recycled fabrics, no environmental reporting, no circular initiatives. The sustainability relevance lies only in slowing down novelty by reusing archives.